This versatile input channel gives you the classic sound of tubes, transformers and inductors.

When reviewing the Hazelrigg VNE compressor (SOS March 2022), I mentioned in passing another of the brand’s products, the VLC single‑channel mic preamp and EQ. If you read that VNE review you’ll already know that Hazelrigg Industries and DW Fearn are intimately connected: the former manufacture and distribute the latter’s products, though Georg and Geoff Hazelrigg also design and hand‑build their own product range, which employs elements derived from Doug Fearn’s designs. Hazelrigg brochures highlight a company ethos of building products that deliver confidence to the end user, combining world‑class sound quality with deliberately simple user controls, which encourage users to adjust and optimise settings by listening rather than by rote.

Overview

So here is the promised review of the VLC, which has been adapted from DW Fearn’s VT‑15 channel strip. Like the VNE, it has a distinctive — austere, even — semi‑vintage look about it, which shares the unfussy brown‑painted front panel of its sibling. It’s a modest, understated aesthetic that many will find classy, even if some feel it doesn’t appear as expensive as it should! Beauty is skin deep, though: it’s what’s inside that really matters, and there’s a lot of very high‑quality tube‑ and transformer‑based goodness inside the VLC!

It all starts with an elaborate power supply and a valve mic preamp derived from Fearn’s VT‑1. There is also an instrument input facility, which borrows from the VT‑IF, and tonal shaping is provided courtesy of a passive inductor‑based EQ derived from the VT4 and VT5 equalisers. The selection and integration of these separate elements creates a unique Hazelrigg product which directly addresses typical practical studio needs, with a sound quality and clarity of purpose that eludes many competitors.

The VLC is a 2U rackmounting unit, although the manufacturers recommend installing 1U vent panels above and below, so in practice it will occupy 3‑4U of rack space. Alternatively, it can be used as a desktop preamp, and optional rubber feet can be supplied if specified at the time of order.

A rear‑panel switch selects between nominal 115V and 220V AC mains input supplies, and a fuse is incorporated into the IEC mains inlet socket. The chassis is grounded via the mains safety earth, but a dedicated chassis grounding stud is also provided on the rear panel, along with two female XLRs to accept microphone and line inputs. A male XLR provides the line output, and both the mic input and line output are transformer balanced.

A rear‑panel switch selects between nominal 115V and 220V AC mains input supplies, and a fuse is incorporated into the IEC mains inlet socket. The chassis is grounded via the mains safety earth, but a dedicated chassis grounding stud is also provided on the rear panel, along with two female XLRs to accept microphone and line inputs. A male XLR provides the line output, and both the mic input and line output are transformer balanced.

Operational controls on the front panel are all clearly marked, well spaced, and use chunky knobs and switches. For convenience, a combi XLR/jack in the bottom‑left corner accepts either a mic input (wired in parallel with the rear socket), or an unbalanced instrument input (via the centre quarter‑inch socket). A three‑way rotary switch with a pointer knob selects the required input source (mic, line or instrument).

Directly above this combi socket is the preamp’s gain control which, as with most Hazelrigg products, has no calibration markings. A single bi‑colour LED in the centre of the panel indicates the output signal level, illuminating green over ‑4dBu and red at +16dBu; the manual recommends adjusting I/O levels so that the unit works mainly in the green zone. Unity gain for the line input is achieved with the gain knob at roughly the two o’clock position, and this position equates to roughly 45dB gain in mic mode (fully clockwise provides 60dB gain).

This gain control is actually an attenuator situated between the second and third valve amplification stages (see ‘Technology & Specifications’ box), and the gain structure is such that the input section normally overloads before the output stage. However, a 20dB pad can be introduced in front of the input transformer if input overload becomes a problem with high‑output sources. One of four toggle switches arranged to the right of the input selector activates this pad, with other toggles engaging 48V phantom power, inverting the output polarity, and enabling the EQ section.

Although there are no status LEDs for any of these switches, the phantom power toggle must be pulled out before it can be moved to avoid accidental operation, and the toggles themselves make their settings quite clear at a glance — up is on! A much larger toggle switch at the right‑hand side powers the unit, and it does have an associated red pilot light.

Passive Voice

So far, so relatively conventional, but the EQ section is quite unusual, both in its design and operation. Hazelrigg have provided four separate passive EQ sections offering independent low cut, low boost, high cut and high boost, all of which can be employed simultaneously. Rotary controls adjust the amount of boost or cut in each band, but although the labelling suggests a maximum of ‑12dB for the cuts and +12dB for the boosts, the reality is not that uniform.

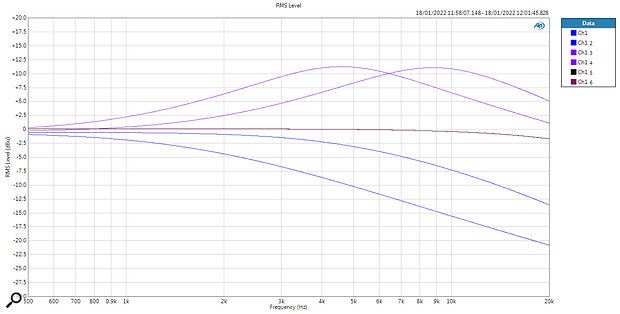

An Audio Precision plot illustrating the range of EQ options. Note the extended frequency scale, ranging between 5Hz and 80kHz.

An Audio Precision plot illustrating the range of EQ options. Note the extended frequency scale, ranging between 5Hz and 80kHz.

Toggle switches for each band select between alternative corner frequencies. So, for example, the high boost control introduces a bell curve reaching a peak of +11dB at either 4.5 or 9 kHz. The high cut EQ turns over at either 1.5 or 5 kHz, reaching over 20dB attenuation at 20kHz (in the lower frequency setting). The low cut section provides a shelf response reaching ‑15dB at 20Hz, with corner frequencies of roughly 250Hz or 1kHz, while the low boost delivers up to +18dB at 50Hz building from either 500Hz or 1kHz. This EQ band has an unusually lumpy response with small peaks around 15 and 50 Hz.

An expanded view of the high boost and high cut EQ bands between 500Hz and 20kHz.

An expanded view of the high boost and high cut EQ bands between 500Hz and 20kHz.

One of the benefits of the passive EQ approach is that the separate boost and cut bands can be employed simultaneously, resulting in more complex response shapes than is possible with the classic Baxandall active EQ. One classic example is the Pultec ‘dip and peak’ response, where the lowest frequencies can be boosted while the cut section introduces a dip a little higher to avoid mudiness.

An expanded view of the low boost and low cut EQ bands between 20Hz and 3kHz.

An expanded view of the low boost and low cut EQ bands between 20Hz and 3kHz.

VLC In Use

The Hazelrigg VLC powers up quite quickly, passing audio within 20‑30 seconds, although I found it could take a few minutes to become completely stable and quiet. The controls are mostly very simple and obvious, and although the EQ section is unusual I found it pleasingly quick and easy to home in on the desired sound shaping. The absence of scale markings on the controls and the fact that there’s no real level metering naturally encourage the user to rely entirely on what is heard to confirm the sound is as needed, and I found that very refreshing.

It was always happiest at the moderate gains typically needed when using capacitor mics, sounding rich and full‑bodied.

I found the tonal character of the preamp changed slightly with different microphone gain settings, and it was always happiest at the moderate gains typically needed when using capacitor mics, sounding rich and full‑bodied — at the highest gains it became noticeably thinner‑sounding. Overall, though, both the mic and line inputs both worked well, with sensible sensitivities and gain ranges. In contrast, the instrument input seemed unusually sensitive, and I needed to engage the pad to capture most instruments. To quantify that, a two o’clock setting of the gain control delivered the reference +4dBu output with just ‑22dBu coming in. Fortunately, with the pad selected, instrument inputs up to about +15dBu can be accepted without problems.

Verdict

Hazelrigg’s VLC is a well‑built and high‑quality valve mic preamp, brimming with character. Its instrument input is a musical bonus, as is the ability to serve as a line‑level processor, adding some transformer and tube warmth for anyone seeking a vintage tone. The unusual EQ section is also effective and well judged for creative tonal shaping, able to add weight and air or reduce mudiness and edginess very smoothly and naturally. Like its sibling, the VLC is easy to use but performs well and has a lovely, classy and musical character that is very beguiling. At this price it’s obviously a luxury purchase — but what luxury!

Technology & Specifications

A view of the VLC’s innards, showing the PSU (top right) and four 6072A valves.

A view of the VLC’s innards, showing the PSU (top right) and four 6072A valves.

The VLC employs four selected 6072A double‑triodes for the entirely valve‑based signal path. Four discrete Class‑A amplifiers make up the main mic preamp section, with each of the first three gain stages providing around 30dB of fixed gain. The fourth is configured as a unity‑gain cathode‑follower to drive the passive EQ section, and the output of the EQ is received by a line amplifier which drives the output transformer.

A variable attenuator located between the second and third stages of the mic preamp adjusts the overall gain, providing a maximum of 60dB for the mic input, 14dB for the line input, and 40.5dB for the instrument input. A pad switch introduces 20dB of attenuation for the mic and line inputs, but only 10dB for the instrument input — a feature undocumented in the user manual. Being a passive design, using custom‑wound inductors, the EQ section inherently attenuates signals passing through it, so when bypassed an internal pad replaces the EQ circuitry to maintain the overall gain structure through the whole unit.

Testing the review model with an Audio Precision test set, most of my measurements agreed with, or bettered, the published specifications. In microphone mode and at maximum gain I measured a THD+N figure of 0.15% (delivering +4dBu at the output) and intermodulation distortion (IMD) of 0.38% (SMPTE), which are good results and considerably better than the published figures. The line input operating at unity gain gave similar results. Naturally, distortion rises with increasing output level, reaching a THD of 1% with +19dBu at the output, and 2% at the maximum output of +22dBu. With the full 60dB of mic gain applied, residual mains hum components remained below about ‑90dBu, and even adding full low boost only brought them up to ‑80dBu, which is impressive.

Hazelrigg’s specifications state that the line input presents a bridging load of 40kΩ, although when tested with an NTI MR‑Pro the measured value was 20kΩ. The mic input impedance measured 1.4kΩ (close to the specified value), and that doesn’t change when the input pad is selected. The instrument input presents a 1MΩ impedance.

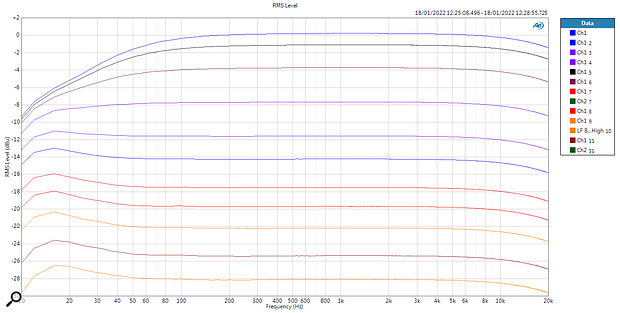

The preamp’s overall frequency response (EQ bypassed) at different gain settings. At the highest settings the low end rolls off early, which can sound noticeably thin. At moderate gains the response is essentially flat, while at the lowest settings a small boost builds up at the extreme low end.

The preamp’s overall frequency response (EQ bypassed) at different gain settings. At the highest settings the low end rolls off early, which can sound noticeably thin. At moderate gains the response is essentially flat, while at the lowest settings a small boost builds up at the extreme low end.

The frequency response is specified as 20Hz and 20kHz (±0.5dB), although I found the HF response rolled off a little earlier, being around 1.5dB down at 20kHz (EQ bypassed). I measured ‑3dB points at 35Hz and 30kHz (see plots), and also noticed that the low‑end response rolled off early below 100Hz when using the highest gain settings. At more moderate gains the response levelled out, albeit with a mild 2dB peak around 15Hz.

An EIN figure of ‑124dBm is stated in the specs, although I doubt that’s really taken with the implied 600Ω termination. My own measurements gave a value of 124.5dB with a 150Ω termination (measured between 20Hz and 20kHz), while the A‑weighted figure is ‑126.5dB — these being good values for a valve mic preamp.

While the specifications are good for a valve preamp, I was disappointed that the company are using outdated and technically inaccurate terms such as CPS (cycles per second) instead of Hertz, and ‘dBm’ — which doesn’t instil confidence. In the same vein, the published product dimensions are not only wrong, but the metric measurements don’t even agree with the imperial ones! I absolutely applaud the inclusion of comprehensive technical specifications, but they are worthless if not accurate — and that includes using the correct terminology and proof‑reading before going to print.

Pros

- Classy and musical sound character with valve/transformer warmth.

- Smooth‑sounding passive EQ.

- Simple but effective controls.

- Very well built.

- Understated aesthetics.

- Seven‑year warranty.

Cons

- Other than the price? Absolutely none.

Summary

Derived from the DW Fearn VT‑15 channel strip, the Hazelrigg VLC delivers a wealth of valve/transformer sonics with a simple set of controls and facilities that really help the user focus on capturing a very classy sound.

Information

£3395 including VAT.

ASAP Europe +44 (0)20 8672 6618

$3400.

Hazelrigg Industries +1 567 393 3276

support@hazelriggindustries.com

https://dwfearn.com/wp/hazelrigg‑industries