Arranger Sally Herbert (second from left) playing in London's AIR studios at a string-quartet session.

Arranger Sally Herbert (second from left) playing in London's AIR studios at a string-quartet session.

Just what should you expect when engaging a professional arranger or orchestrator to work on your own production? We find out from some of the best in the business...

Countless musical productions in all sorts of genres have benefitted from the addition of brass, woodwind or strings, and in almost every case a skilled arranger or orchestrator will have taken the ideas of the composer or producer and transformed them into a score that musicians can work with quickly and efficiently. It’s also very common for the arranger to conduct the recording session, and on other occasions the arranger may act as a sub-producer, overseeing proceedings from the control room and tweaking the arrangement on-site to better fit the other elements in the mix.

To help give you a better understanding of what it’s like to work with these skilled professionals, I spoke with two leading arrangers, Sally Herbert and Nick Ingman — you can find out more about them in the ‘Meet The Experts’ box. I asked them to reveal how they turn a composer’s ideas into orchestral scores, and to describe the type of material a composer should, ideally, provide an arranger with.

Source Material

Obviously, an arranger has to be given a composition before they can start work, but the material that they receive varies hugely from job to job. Nick and Sally have experienced it all, from the very good to the extremely bad.

“It’s everything from sitting in a room and the artist playing the guitar to you, to a completely finished track, with everything on it except what you are about to do,” says Nick. “The perfect setup is MIDI files, Sibelius files, audio, and maybe something printed out. That’s very unlikely, but it can happen.”

“Sometimes I’m given a song demo and there’s no clue apart from what the producer says, and its up to me,” adds Sally. “Sometimes the bands will give me MIDI files, which is often difficult. A lot of people plonk something on a keyboard and assume it’s an arrangement but it can take a long time to sort out for recording with the instruments we’re using... If they’ve played a particular hook line then that makes total sense, but it’s sometimes harder if they’ve used a fake strings sound as a kind of pad or to fill up space. Then you have to find out if they really want it to sound like that. You have to ask a lot of questions to get to the bottom of why they put it in and if they want you to improve on that or add more. You don’t want to overdo it but at the same time you need to find out if the band are expecting a lot more.” Nick Ingman putting some notes down the old–fashioned way.Photo: Liz Norden

Nick Ingman putting some notes down the old–fashioned way.Photo: Liz Norden

Nick is also no fan of rough approximations played on keyboards. “The worst package is when the composer is so musically illiterate that they’ve played stuff instinctively on a keyboard without any knowledge of what they’re doing,” he insists, specifically referring to film scores. “What happens a lot is a very successful pop artist gets hired to write a film score because they have what’s called ‘marquee value’. It makes very little sense because the two disciplines are so different. They tend to create the score in the way that they work when doing pop music and give you the most approximate thing, and that’s tricky for us in the back room. The issue is that he or she may not have been able to completely express the idea in their head, so there is a disconnect between that and what I am making the best of.”

Nick has often encountered a similar problem when asked to interpret the ideas of pop and rock bands. “It always seems to fall to the keyboard player [to compose the score] and inevitably they play the strings like a keyboard player — which is not the best way to make a string section sound good! It can be alright, and there are lots of instances where that has happened and the arranger simply transcribes that idea, but most of the time we’re hired to take it a stage further.”

So if you want string, woodwind or brass parts and you’re not musically literate, how best can you communicate your ideas to an arranger? On some occasions the arranger is not given MIDI or audio, but the name of a piece of music to use as an example of what’s required. “I’ll often have someone describing a song or album they are influenced by, which is quite a good clue as to what style they want the strings or brass to sound like,” says Sally. “I like to know what they have in mind but I’m happy for them to tell me in words. If they give me a few string ideas that’s fine, but I’m usually happy to hear about influences or styles. If they say ‘We want a big tune here,’ or ‘we want something to give a bit of texture to the chorus,’ that’s usually gives me enough of a clue to get it right.

Nick is frequently briefed with similar requests. “Most of the time they ask you to make it sound like what we call ‘role models’. Can it sound like Led Zeppelin? Can it sound like Olly Murs? That’s the question because they need to know that they are going to get what they want. That’s the pop business, in essence.”

In A Perfect World

It’s clear from what Sally and Nick say that arrangers and orchestrators are usually prepared to work with most briefs, no matter how vague they may be, but they have clear recommendations to offer those composers who are willing to supply an arranger with high-quality source material.

“You need to provide a demo of your song,” begins Sally, “and if you have a guide string or brass part, you can have one version with it on, and one without, for the arranger to work on. It’s useful to give a MIDI version of what you have played so the arranger doesn’t have to decipher what it is. It can be quite tricky to work out what someone has put into a track on a fake string or brass sound, because it can get mixed up in guitars and other things.

“Give guidelines, but keep the idea simple. If there’s a theme you want the orchestra to play, put that in, but don’t take it too far or overcomplicate it. Leave it to the people who are used to doing it.

“If you can’t afford an orchestra or a strings section, which most bands can’t, you can sometimes find players who will help you out, but,” she advises, “keep it really simple again, and use the strings or the brass more texturally to bring out one line. Don’t try to create a masterpiece if you are not sure what you’re doing! And if you are producing a manuscript, ask the players for advice. You may think that it looks all right in Logic but it’s always worth asking someone if it is readable and in the right clef.

The scoring facilities built into DAWs such as Logic might be all you need to produce a score for basic pop/rock arrangements, if not for more complex classical styles. But remember that the MIDI information required to play some virtual string or brass instruments is very different from what’s needed to generate a score that musicians can follow.

The scoring facilities built into DAWs such as Logic might be all you need to produce a score for basic pop/rock arrangements, if not for more complex classical styles. But remember that the MIDI information required to play some virtual string or brass instruments is very different from what’s needed to generate a score that musicians can follow.

“A lot of bands say they’ve done the scores, but when you get there you find the violin in the bass clef and they haven’t realised that violas play in a different clef to violins. Or they have played it on a keyboard without quantising and just printed it out. MIDI files can be confusing when not quantised. Even if it sounds alright as MIDI, the score can be unreadable, and if you are asking people for favours that doesn’t go down so well!

“Logic is fine for scoring a small section like a quartet but I do quite a lot of classical crossover for people like Sarah Brightman and Catherine Jenkins, and it’s pretty awful for things like that, so I get an arranger called Olli Cunningham, who works with me occasionally, to put it into Sibelius and then we make a clearer set of parts. That’s important because often those artists will take that on tour. I literally print out my Logic score, write notes on it, scan it back, and give that to him.

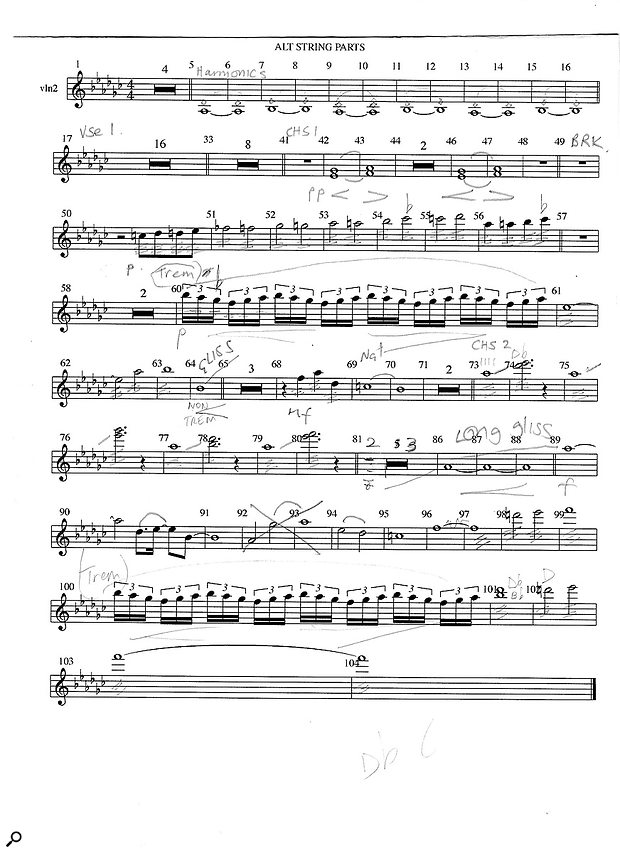

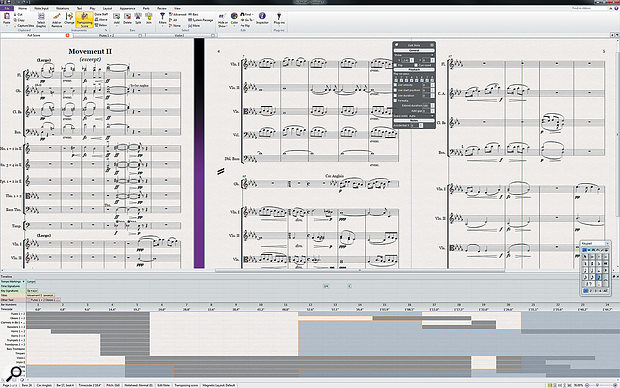

When presented with a basic score from DAWs such as Logic or Cubase, an arranger might make manual annotations, and have someone turn their scrawls into a tidy score using a dedicated application such as Avid’s Sibelius.

When presented with a basic score from DAWs such as Logic or Cubase, an arranger might make manual annotations, and have someone turn their scrawls into a tidy score using a dedicated application such as Avid’s Sibelius. Avid Sibelius.

Avid Sibelius.

“If you are expecting the musicians to listen to the song and pick it up that’s fine, but make sure they are pre-warned. Experienced players are usually quick at picking up a line, as long as it’s clear and they can hear the track a few times.”

Sally also has some advice for anyone wanting to avoid paying for a commercial studio. “I’d rather not try to record strings in someone’s bedroom because the acoustics can be a problem. If you haven’t got an AIR Studios or an Abbey Road, where the instruments sound glorious whatever you do, you sometimes pick up horrible frequencies, particularly with strings, so it’s probably better if it is acoustically dead — you can add the reverb later. You also need space. If it’s just one violin or cello you don’t need much, but if you have a quartet sitting down with four music stands and four chairs it takes up more room than you might think!

“If you are not sure what you want then the best thing is to have a chat with the arranger and describe how you’d like it to sound overall, what your influences are, and how big a part you want the arrangement to play. Flowing, melancholic, lovely and uplifting are the sort of words I hear a lot! I don’t usually get sent lyrics but sometimes the artist feels it’s important that I understand what the track’s about, which is fair enough.”

Providing Stems

Nick asserts that the arranger’s skill is to take whatever they’re given and make it work, and he says that he is always keen to receive instrument or group stems along with the main mix so he can properly analyse the material and match his score.

“It’s always helpful to have stems because then I can really get into the track and find out what’s happening in each bar,” he explains. “If the bassist is playing sevenths in the chord, for example, that could be interesting, but that’s sometimes hard to hear when you get the whole track.

“If I am adding a string section which has a bass part, I’ll want it to play along with the synth or electric bass and I need to be very precise so that the harmonic structure and the rhythm are correct. But I’m also listening out for mistakes! That’s always interesting because if the bass player wasn’t absolutely on it you have two options. You can go back to the producer and say ‘Do you really mean that in bar seven where he is playing an A and the band is playing a B chord?’ He may say ‘Yeah, it’s fine, what’s your problem?’ In that case then you go with the ‘mistake’, and you make a meal of it. Unless it’s really catastrophic, you have to underline it and make an issue of it, otherwise it gets lost in the undergrowth and sounds wrong.

“There are thousands of instances where there are ‘wrong notes’ in a pop tracks, particularly where people are singing a note that’s not in the chord, and often the track is massively interesting and successful, so the rules go out the window. You have to make a judgement as to whether it is interesting or just a mistake.

“A mistake can be something very basic, like plagiarism: people copying ideas consciously or unconsciously. Or notes that are not happy in the chord and sound wrong. More normally though, too many ideas is the problem. Embryo arrangers always make the mistake of using too many ideas. The reality is, in pop particularly, that the string part is not a big part of the picture. So if the embryo arranger comes along with 10 ideas it becomes a sonically crowded mess. It’s better to have two really good ideas and put them fairly upfront in the mix and then live with that, instead of having a whole bunch of stuff in the background which you don’t really hear.”

When asked if one of the problems is instruments clashing in terms of their sounds and articulation details, Nick is insistent that there is no simple rule to adhere to, only professional knowhow. “I think it’s a choice thing,” he says. “It’s not wrong or right instruments, it’s just what works with the track. If you listen to Motown records from the ‘60s or ‘70s, they had pretty much everything there — brass, strings, woodwind, harp, you name it — but it was done with such skill that it works. They were trained classical musicians and knew what combinations would make a good sound, so that was their skill as hopefully ours is now.”

Studio Craft

Although orchestral arrangements tend to be added to pre-recorded productions, the arranger often has to be ready to alter their work when there are late changes to the mix or basic arrangement. Sometimes the arranger gets asked to write the score with reference to a demo, only to find that by the time they start recording the orchestral parts, the track has moved on! Needless to say, it is better to keep the arranger in the loop and indicate, if possible, whether or not the track is finished or in a state of development.

“Pop is difficult because it is a work in progress until it becomes a record,” confirms Nick. “It’s being constantly tampered with because that’s how it works, but when I come in I need to know where they are in the timeframe. Often, they are not finished and you have to keep going back to them, so when you finally get in the studio you are not surprised to find the track is in a different key or tempo!

“I worked with Oasis a lot and they were constantly changing things. On one occasion, I turned up to a session with a string section, having written this score to a track I’d been given, and they were playing something in the room. I said, ‘That’s a nice song, what is it?’ and it was the same track! It was unrecognisable, so I had to rewrite the score there and then.”

“Part of my job is to be there during recording, and if things need changing on the spot I have to be able to do that,” adds Sally. “You often have to cut or add things, which is stressful when you first start, and I used to take it terribly personally, but that happens all the time. If you are recording guitar or drums in the studio you’d do that, and orchestral parts are no different, it’s just that you might have 30 people waiting for you to change the part!”

Sally’s solution to the vagaries of pop production is to work with a regular group of players, who are capable of adapting to changes very quickly and improvising when necessary. During a typical recording session, she is apt to consult her players to ensure she is getting the best possible results from them, and this is especially true when tweaks and changes are being made.

“If you have a quartet,” she explains, “then that’s small enough to discuss what you are going to do, and I always take on board the ideas of others, but I don’t encourage it in a much bigger section,” she continues, ”because if everyone has an idea it’s time consuming. For a bigger section you’ll have the leader. There is a guy I work with a lot called Everton Nelson, and quite often we’ll discuss the part and he becomes the mouthpiece for the section. Or the lead cellist will come into the control room and we’ll listen to the recording, so you have three or four people with ideas.

If the arranger is also playing on the session, then that adds a layer of complexity. “If it’s a big orchestra,” Sally continues, “I’ll be conducting, or I will be in the control room listening, but sometimes when it’s a string quartet I’ll be playing the violin and I’ll be going in and out of the control room all the time, because you have a very different balance through the headphones in the live room and you have to hear how it is sitting in a track... You might have the drums loud in your headphones if it’s a rhythmic part, but the track will be fairly quiet and the likelihood is that the vocals will be low because vocals can interrupt the tuning. When you are trying to concentrate on tuning you need to listen to, say, the piano or acoustic guitar. The voice or an electric guitar that’s moving about a lot can be really off-putting. So you need to hear how it is sitting when the vocal or the guitar is up, and make sure the tuning is working and not interrupting the vocal.

“The things that I change the most are those that get in the way of the vocal, and I usually have to simplify them. The tendency is to be too fussy because it is hard not feel your instrument is the most important! And because the strings are often in the vocal range, when you hear the real strings against the vocal you sometimes find that they are covering up a word, complicating a rhythm or not sitting quite right.... Most of the time strings are not important on the track; they are just another element, so my job is about keeping things very simple. The main thing I’ve learnt over the years is to stay out of the way and not push it.”

Final Thoughts

The modern arranger is multi-skilled, flexible and creative, which is great news for composers, producers and artists who want orchestral instruments on their tracks. Even if your idea is sketchy, the arranger should be able to develop it to fit the track, adapt the score to changes made in the studio, and instruct musicians accordingly. Ultimately, though, the composer must understand what an arranger will and won’t do, and be able to provide them with suitable material to work from.

Meet The Experts

Sally HerbertSally Herbert was classically trained at the Guildhall School of Music, but in her final year she landed a job in a quartet touring with the Communards, and decided that working in pop was more fun than following the classical route. After a brief stint as one half of the pop duo The Bandaras, she found herself arranging for producer Mike Hedges. “I was doing sessions as a violinist for Mike at a time when the Manic Street Preachers were recording ‘A Design For Life’ and there were lots of big-sounding tracks about,” explains Sally. “One day, his arranger didn’t turn up and he asked me if I wanted to do an arrangement. That was it and I started building a career and meeting other producers and bands.

Sally HerbertSally Herbert was classically trained at the Guildhall School of Music, but in her final year she landed a job in a quartet touring with the Communards, and decided that working in pop was more fun than following the classical route. After a brief stint as one half of the pop duo The Bandaras, she found herself arranging for producer Mike Hedges. “I was doing sessions as a violinist for Mike at a time when the Manic Street Preachers were recording ‘A Design For Life’ and there were lots of big-sounding tracks about,” explains Sally. “One day, his arranger didn’t turn up and he asked me if I wanted to do an arrangement. That was it and I started building a career and meeting other producers and bands.

“The producers I’ve worked with now trust that whatever band they get in I’ll be able to come up with something or I’ll be able to pick up what they want very quickly. Occasionally a band or composer hears what I’ve done and contacts me, but it tends to be through producers. I work with whole orchestras, but for pop I generally do strings, brass and choirs.”

Nick IngmanArranger and conductor Nick Ingman studied under jazz composer Graham Collier before following in his mentor’s footsteps and heading to Berklee College of Music in the United States. When he returned to the UK he landed a job working for producer Norrie Paramor, alongside Tim Rice. “That was a massive learning curve,” says Nick. “I started to do arrangements when Norrie was too busy to do his own and when he was preparing to retire he handed over all the arranging and conducting to me. In those days, it was bottom-up arranging — in other words, the full score including drums, bass, guitar, strings and brass, and everything was played together in one room. The big rooms like Abbey Road were the main studios, and it would be 40 to 60 people recording four tracks in a three-hour session, complete from top to bottom. It was a huge discipline on everyone’s part, and the performances had to be absolutely flawless first time. All these huge names like Jimmy Page and Jim Sullivan were just jobbing musicians and would come in and do sessions.

Nick IngmanArranger and conductor Nick Ingman studied under jazz composer Graham Collier before following in his mentor’s footsteps and heading to Berklee College of Music in the United States. When he returned to the UK he landed a job working for producer Norrie Paramor, alongside Tim Rice. “That was a massive learning curve,” says Nick. “I started to do arrangements when Norrie was too busy to do his own and when he was preparing to retire he handed over all the arranging and conducting to me. In those days, it was bottom-up arranging — in other words, the full score including drums, bass, guitar, strings and brass, and everything was played together in one room. The big rooms like Abbey Road were the main studios, and it would be 40 to 60 people recording four tracks in a three-hour session, complete from top to bottom. It was a huge discipline on everyone’s part, and the performances had to be absolutely flawless first time. All these huge names like Jimmy Page and Jim Sullivan were just jobbing musicians and would come in and do sessions.

“As an arranger, I had to know all the instruments, their ranges and what sounded best — you are a multi-instrumentalist, even if you are not actually playing stuff! One of the good things they did at Berklee was make you learn to play the C major scale on every traditional instrument, so you had a working knowledge of pretty well everything.

“The modern pop scene, as far as an arranger is concerned, is adding strings or brass or whatever onto existing tracks created by the producer or the artist in a small MIDI studio. Very rarely any more do we arrange from the bottom up, including drums and so on.”

To Click Or Not To Click

Anyone intending to add orchestral arrangements to their recordings needs to consider whether or not it will be necessary to supply a click or guide track. A dance or rock track with a strong drum part effectively has a click already, but a piano ballad, for example, might be based around the ebb and flow of the performance, and that can be difficult for a section to follow without a more obvious guide.

“ If it is just straightforward drums and bass we won’t need a click, it’s only when thing are sparse,” confirms Sally. “Overdubbing is tricky if you are trying to match things exactly. It can be hard to pick up the starts of bars, especially when there are four or more of you trying to come in at the same place after a gap.”

“Mostly we work to click tracks, but not always,” adds Nick, referring to film score work. “Some composers believe clicks make the music too rigid, so sometimes we free-conduct. But there is a whole bunch of software — Auricle is one example — that helps you do that. You have your own screen showing the film and on it will be flashes that tell you where you are in the bar, and so on. It’s the music editor’s job to produce these, but you may sit down with them and say ‘Can I have a blip here, a spot there, a flash there?’”

Arranging For Film

Alongside his career arranging for pop tracks, Nick works as an orchestral arranger and conductor for film scores. Here, he explains where the differences lie.

“The film business is very tricky because right until the last minute films are being edited quite drastically, and if the composer is working — as mostly they are — to cues that are very precise, and the edit is screwed around with, then suddenly what’s written is wrong. That’s where the music editor comes in, because they are constantly updating the composer with the latest versions. They are a link between the composer, director or film editor, and are very crucial to that process.

“And then I come in and turn the composer’s approximate ideas, mostly presented as electronic demos, into reality. The demos are usually very good and precise, making use of string libraries and a whole bunch of stuff that’s out there.

“When we record an orchestra, I usually conduct, although that’s not always the case. Film music conducting is a very special art requiring lots of techniques that are not used in any other field. The main thing is that the conductor has to be precise. He or she has to bring the orchestra around to the right place at exactly the right time. If you listen to scores that were recorded in the 1940s, before click tracks were common, you can hear the music coming to a cadence, a climax, where the cowboy shoots the bad guy. There’ll be a big chord, and you can hear how the conductor brought the music to that point and held that chord until the Indians ran away! You can hear the music being manipulated.”