![]() Strip Silence can be a quick way to chop up narration, but it takes fiddling around to get the settings right, and some amount of adjustment will be needed to events as you proceed with editing.

Strip Silence can be a quick way to chop up narration, but it takes fiddling around to get the settings right, and some amount of adjustment will be needed to events as you proceed with editing.

We offer some tips on working with speech in Studio One.

Podcasts, radio drama, audiobooks, news stories... there is a lot of audio‑only work around today that focuses on the spoken word. Working with narration is different from dealing with sung vocals, but Studio One is well equipped. There are a few tasks, such as noise removal, that may require third‑party plug‑ins, but Studio One’s bundled processors are adequate for handling pretty much everything else.

This month I will give some tips to help you get great narration tracks for your projects. There can be a lot of variation in the nature of projects, the narrator’s voice, the recording equipment and the recording environment, so no hint can fit all situations. As always, the quality of the raw recordings is key to the final result, but that discussion is beyond the scope of this little column. That qualification made, let’s talk.

Cut & Cover

It is exceedingly rare for a narration track to get used without edits, and one sometimes encounters level and tone changes across the narration in a project. Cutting narration into chunks facilitates handling both of these circumstances, but longer chunks make a better jumping‑off point than events of only half a sentence.

The Strip Silence command is one quick way to cut up narration. Set the Minimum length parameter to 1 second, the longest value available. Use generous Pre‑roll and Post‑roll settings; I’ve often used 500ms or more. Shorter values can cut off quiet details, such as the end of a ‘t’ sound after the main transient, that are more noticeable in narration than in a sung vocal with a band.

After chopping, delete events that are obviously undesirable noises: paper rattling, throat‑clearing and so on. Insert basic high‑pass filtering with Pro EQ or Fat Channel to get rid of thumps and excessive proximity effect, and use low‑pass filtering to reduce fan noise and other high‑frequency garbage if present. You don’t generally need bandwidth up to 20kHz for the spoken word.

At The Edit

The actual process of editing the wanted audio into a coherent narration can be a huge task. Turn Snap off for greater precision in making edit cuts. Double‑click at the edit point to split an event. Select the narration track and press Command (Ctrl on Windows)+Shift+A to select all events on the narration track, then drag at the beginning and the end of any selected event to create top and tail fades on all events. Note that fades will already exist on events created using Strip Silence with pre‑roll and post‑roll. I find exponential fade shapes most often sound the best on speech.

If your desired edit point sounds rough, try moving the edit point a word or two before or after. Save a new version whenever you’ve done a tricky edit, or enough edits that you’d be upset to lose them. Give the version a useful name that squeezes in enough information for you to figure out later why you saved it. Consider smoothing edits by adding some small room ambience on the narration track or adding room tone between edited events.

Studio One’s nudge feature uses grid snap, so nudge amount is expressed in musical terms. This chart shows the nudge amount in milliseconds for given tempo and quantise values.The importance of timing and pacing in narration cannot be overstated. Shifting a phrase or sentence by a small amount can make a noticeable difference in the flow, and getting this right means repeatedly auditioning a small section while sliding an event earlier or later. A nudge function is the most efficient method for this, but Studio One’s nudge function is based on musical values, not absolute time, which presents a few issues. The biggest is the impact of tempo. If you only have narration in your session, you can set the tempo to its maximum of 400bpm for the finest nudge resolution. You won’t have this flexibility if there are music or sound design tracks in the same Song document, when changing the tempo will cause obvious problems!

Studio One’s nudge feature uses grid snap, so nudge amount is expressed in musical terms. This chart shows the nudge amount in milliseconds for given tempo and quantise values.The importance of timing and pacing in narration cannot be overstated. Shifting a phrase or sentence by a small amount can make a noticeable difference in the flow, and getting this right means repeatedly auditioning a small section while sliding an event earlier or later. A nudge function is the most efficient method for this, but Studio One’s nudge function is based on musical values, not absolute time, which presents a few issues. The biggest is the impact of tempo. If you only have narration in your session, you can set the tempo to its maximum of 400bpm for the finest nudge resolution. You won’t have this flexibility if there are music or sound design tracks in the same Song document, when changing the tempo will cause obvious problems!

Nudging requires snap to be enabled, so nudge time is determined not just by tempo, but also by the quantise value, which is also specified in musical terms. The chart in this article translates tempo and quantise values into nudge times in milliseconds. Note that at the maximum tempo and smallest quantise value, the nudge time dips just below 10ms, which is fine for most purposes. For finer resolution, turning snap off sets the nudge value to 1ms.

To check pacing, listen to entire sections; listening to just a few seconds on either side of an edit does not give enough context to put timing in perspective.

Main Events

Event volume is an excellent primary tool for levelling narration. In this example, the highlighted event has not yet been levelled, while the others have.

Event volume is an excellent primary tool for levelling narration. In this example, the highlighted event has not yet been levelled, while the others have.

The best tool to rely on for basic level management is event volume. Use Option (Alt) with the plus and minus keys to adjust this parameter for the selected event(s). The aim is to obtain a healthy basic level that leaves a fair amount of headroom across the board, then drag event volume handles on an event‑by‑event basis to get levels fairly even through the whole piece. Individual words or parts of words that are too soft or loud can be smoothed with automation and/or compression; your first goal is getting everything in the ballpark.

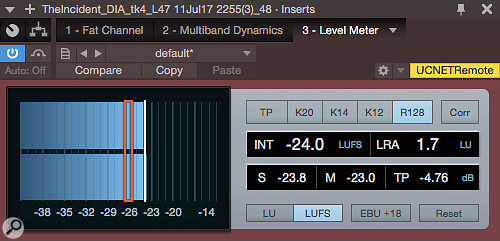

Set markers in key locations and jump between them to ensure the level is approximately constant throughout. Insert the Level Meter plug‑in on the narration channel, if there is only one narration track. If there is more than one, send them all through a bus channel and insert the meter on that. Be sure it is placed after all other plug‑ins. Click the R128 button for loudness metering, which will be the most meaningful. I usually target an integrated value of around ‑24 LUFS.

Although your ears are always the ultimate guide, metering can be helpful, especially loudness metering. This screenshot happens to catch the narration at an ideal integrated level of ‑24 LUFS.

Although your ears are always the ultimate guide, metering can be helpful, especially loudness metering. This screenshot happens to catch the narration at an ideal integrated level of ‑24 LUFS.

The Light Touch

A well‑recorded voice may need little in the way of general EQ, just touching up. A substantial amount of gain may need to be added to very quiet words, which can result in their coming across as bass‑heavy. Add a Pro EQ plug‑in with a high‑pass filter set to reduce boominess and automate its bypass to kick it in just for those moments. At the other end of the spectrum, it is better to avoid incurring sibilance than to have to fix it, but large‑diaphragm condensers can add sizzle. The Multiband Dynamics plug‑in can be set to do a good job of de‑essing, though there is not a factory preset for that.

The Fat Channel is a great toolkit for processing narration. Note that the HPF is set fairly high, just a bit under 200Hz. Other than that, all of the processing is quite light: expansion, compression, EQ and limiting. In this shot, neither expansion nor limiting are acting at all.The Fat Channel XT plug‑in is a great tool for voice work. It has a high‑pass filter, a limiter for catching peaks, and a compressor as well. You can experiment with the different types of EQs and compressors; I most often find the tube compressor and passive equaliser work well, though heaven knows the FET compressor has been used on many, many narration projects. Hopefully you won’t need a gate, but a touch of light expansion can reduce noise a bit in a way that would otherwise be pretty labour‑intensive. Now that we are talking about dynamics, I suggest using a light touch in general, with even the loudest moments triggering only 6‑8 dB of gain reduction, and maybe 0‑3 dB elsewhere, with short attack and decay times. Heavy compression is actually a sound most people are used to on speech, so there can be some slack if you really need to squeeze hard.

The Fat Channel is a great toolkit for processing narration. Note that the HPF is set fairly high, just a bit under 200Hz. Other than that, all of the processing is quite light: expansion, compression, EQ and limiting. In this shot, neither expansion nor limiting are acting at all.The Fat Channel XT plug‑in is a great tool for voice work. It has a high‑pass filter, a limiter for catching peaks, and a compressor as well. You can experiment with the different types of EQs and compressors; I most often find the tube compressor and passive equaliser work well, though heaven knows the FET compressor has been used on many, many narration projects. Hopefully you won’t need a gate, but a touch of light expansion can reduce noise a bit in a way that would otherwise be pretty labour‑intensive. Now that we are talking about dynamics, I suggest using a light touch in general, with even the loudest moments triggering only 6‑8 dB of gain reduction, and maybe 0‑3 dB elsewhere, with short attack and decay times. Heavy compression is actually a sound most people are used to on speech, so there can be some slack if you really need to squeeze hard.

To add presence, try a gentle broad boost, no more than 2dB. Low‑frequency boominess may require a narrower, deeper treatment. If you really need EQ flexibility, the standard EQ will probably be the ticket.

Frosting The Cake

With the basics in place, consider a few other finishing touches. One is simply adding a few dB of more limiting, now that everything else is done, to get it all feeling bigger. Beware of introducing sibilance or harshness.

Spreading narration just a little bit into stereo can make it feel richer. There are a few ways to do this. One is to use the Beat Delay set to a short note value with no feedback and moderate width. Be subtle: mix in just a very little bit. Alternatively, the Open Air convolution reverb can be used. Start with a very short setting, such as the Bedroom factory preset, turn off Cross Feed and set the ER/LR mix close to or at ER entirely. Again, only mix in a little. You can try other stereo synthesis methods, but keep the image relatively narrow.

Finally, if there are music or sound design elements, try submixing them to bus channels, inserting a compressor, and feeding the narration submaster to the compressor’s side‑chain. Adjust for light ducking, maybe 3dB of gain reduction.

On the whole, narration performances are more consistent than sung vocals, but they can also be more exposed, requiring greater attention to fine detail. If the basic recording is good, you may do a lot to the track, but it all might be with a light touch. Done right, the result can be rich and smooth, yet impactful.