Immersive audio is a powerful way of presenting live music — and it’s becoming more and more accessible to independent artists.

When I delivered my first immersive set in 2019, the addition of spatial audio was not something that had even crossed my mind. At the time I was gripped only by the desire to create a show uniting electronic music with visuals — creating something to take an audience out of their day‑to‑day experience — and was working with designer Jan Petyrek to achieve this.

Jan and I were searching for venues to test out our nascent AV set when we were offered a last‑minute slot at a Hackathon event at Abbey Road Studio 2, the aim of which was to encourage participants and performers to innovate. The company providing the sound system, L‑Acoustics, explained they were bringing a 12.1 system into the venue, and suggested I might like to program the set for this setup. This seemed intriguing, and with encouragement and guidance from their engineers I was able to reformulate my set using their L‑ISA software in just a couple of days.

Live For Live

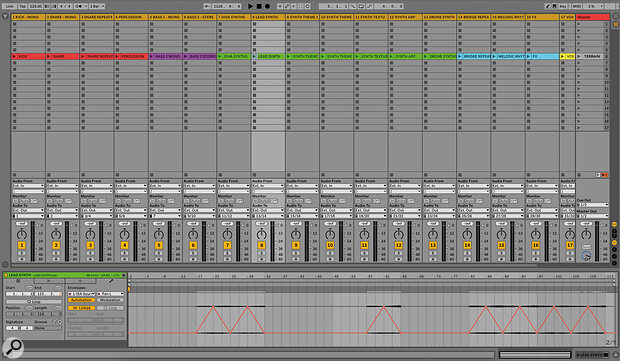

Like many electronic music producers, I use Ableton Live for both production and performance. For my live sets I was already used to bouncing audio of each track into component stems such as kick, percussion, bass, effects and synths, and placing these into a number of scenes in Ableton, with each scene triggering a whole track. I would then add a variety of instruments and samplers into the Ableton set to play live over the audio playback.

The author’s setup uses Ableton Live and L‑ISA from L‑Acoustics.Photo: Chloe Hashemi

The author’s setup uses Ableton Live and L‑ISA from L‑Acoustics.Photo: Chloe Hashemi

The first time working in L‑ISA introduced me to the now‑familiar process of stemming my tracks in a much more granular way to create audio objects for spatial mixes. In brief, spatial audio gives you the opportunity to place and animate all of these audio objects, aka sound sources, independently within the auditorium. An L‑ISA Processor — either physical or virtual — maps the objects to the physical speaker array to convey the spatial mix you have created. The programming to achieve a spatial mix involves adding metadata to each created audio object. (For more about the principles of object‑based mixing, see our 'Introduction To Immersive Audio' article in the January 2022 issue.)

Metadata can include information about panning, elevation, and even effects such as distance created through the addition of dynamic reverbs. These can all be changed over time, either using snapshots within the software engine or — as felt more comfortable in my workflow — using L‑ISA plug‑ins in Ableton Live and drawing in automation. These then communicate with the L‑ISA Controller, which integrates information for all your audio objects, speaker setups and monitoring options and also includes a spatial effects engine.

These days, I might create between 10 and 20 stems depending on the project. The idea is to achieve a good balance between the number of outputs and programming required, and the flexibility to treat sounds differently. As an example, if you bounced a synth and a vocal sample together in the same stem, they would receive the same metadata and would be placed in the same way around the room, which may not be the desired effect. However, you can group multiple granular stems in the L‑ISA software if you actively want them to receive the same metadata; for example, you could group a number of synths together and place them around the room in one go.

The L‑ISA plug‑ins allow spatial audio metadata to be written directly into a Live session.

The L‑ISA plug‑ins allow spatial audio metadata to be written directly into a Live session.

Advance Planning

For that first project at Abbey Road, the main challenge was monitoring, and this is still a key issue for the development of immersive sound today. At that time, the only way to audition my programming was within a multi‑speaker monitoring setup, and I completed much of the object‑based mix at the L‑Acoustics Creations showroom studio in Highgate with an 18.1.5 studio speaker array. In the words of Ferris Bueller: “It is so choice. If you have the means, I highly recommend picking one up.” But that luxury isn’t often available, and many people need a more affordable and portable way to test out their panning and effects choices.

In 2021 the launch of the L‑ISA Studio suite brought the addition of binaural headphone monitoring, a feature also available in other popular spatial audio software such as the Dolby Atmos Renderer. Binaural monitoring uses psychoacoustic techniques to emulate how we perceive sounds coming from behind or above us. There is also the option to use a head tracker, which allows a more fully realised rendition of a 360‑degree space, constantly reinterpreting the sound as you turn your head. In my experience, binaural monitoring has never sounded exactly like the eventual room setup, but it gives a clear enough idea of the movement of sound objects to enable me to program a set using headphones. Even for reproduction in stereo, a venue can sound radically different from a studio mix and require some adjustment, so I don’t think spatial audio brings any new challenges here.

That initial, experimental Hackathon opened a door for me to consider using spatial audio in future shows, adding to the palette of options with which to create immersive experiences. It had particular relevance to my practice, as the compositions ranged from pure sound design — delivered all around the audience — to beat‑driven IDM tracks, which benefit from a static frontal image (kick, bass and so on) enhanced with effects and synths placed around the auditorium. I was excited to push forward — and then Covid happened, and these ambitions were put on hold.

Multi‑format

By the end of 2021, the world was opening up and live performance became a possibility again. In the intervening time, I had been building up the visual aspect of my set, incorporating generative art and elements of mixed reality. In addition, I had developed my amateurish skills in programming lights, and was keen to put all these elements together with spatial audio to create a coherent immersive show. But where and how could such a show be presented?

Although there are some entry‑level venues that have spatial sound systems, and more are slowly emerging, the number is still quite small. There are good reasons for this: it’s more expensive than stereo to fit and maintain, and as immersive audio is still a niche area for most artists and genres, there is rarely a requirement on the venues to have such systems, nor is there necessarily the content available. Audiences still have minimal familiarity with immersive sound and are content to receive audio in stereo or even mono, even though their experience may be enhanced when presented in spatial audio. With these factors in mind, venue operators are naturally hesitant as to whether a spatial system would pay back the investment in time and money.

A good example of a forward‑thinking, emerging space is Dareshack in Bristol, where co‑founder and creative director Adda Cohn has pioneered the implementation of a d&b Soundscape system into a 200‑capacity venue so that grassroots AV groups can trial immersive content. Unfortunately, this is still a rarity, so if you want to put on an immersive live show, you may well find yourself needing to hire in a system.

A 12‑speaker immersive setup at the Copeland Gallery.Photo: Michael Augustini

A 12‑speaker immersive setup at the Copeland Gallery.Photo: Michael Augustini

For my first post‑pandemic show, I was fortunate enough to have some support from Arts Council England and so took the route of hiring both venue and sound system. A 12‑speaker L‑Acoustics system was installed for three days at the Copeland Gallery to implement both a daytime installation piece and two evening performances. The job of fitting the audio, projections and lighting into the venue seemed for a while to be overwhelming, but the audience reaction was so intensely enthusiastic that the general indication was that there was something in this formula to pursue.

Down To EartH

Following this experiment, I was keen to find other venues where I could present the immersive show. The natural progression in London was to take this to EartH Hackney: a 670‑capacity venue built in a reclaimed theatre, where a 17.1.8 in‑house L‑Acoustics L‑ISA configuration made it easy to integrate my existing set, and the L‑ISA‑trained in‑house sound engineers ensured the sound had great delivery on the day. The main consideration in preparing my set for this space was to do with the layout of the venue and the system. At the Copeland Gallery, we had had a true 360‑degree setup with identical speakers placed evenly around the space. By contrast, the setup at EartH is more akin to the arrangement you might find in an arena, with the majority of speaker power along the front of the stage and supplementary speakers to the sides, back and ceiling of the auditorium. This still allowed enough scope for some playful positioning and movement of sounds across the audience, and again the reception was very enthusiastic.

The EartH speaker setup modelled in L‑ISA.

The EartH speaker setup modelled in L‑ISA.

The EartH show highlighted another benefit of an immersive system: the ability to achieve coverage in a larger space. This was also evident at a performance I did at a church in Berlin: an unusual though beautifully designed round space where half the audience were on the ground floor and the other half on a mezzanine level. For this show, a 16‑speaker system was brought in with speakers encircling both levels. In this instance, spatial audio was an effective tool for a Heineken-style effect of reaching the parts other setups could not reach.

EartH in London is a slightly more conventional performance space with a stage and a well‑defined ‘front’.Photo: Michael Augustini

EartH in London is a slightly more conventional performance space with a stage and a well‑defined ‘front’.Photo: Michael Augustini

Lost In Translation

Just because a venue is equipped for spatial audio doesn’t meant their system will necessarily integrate so easily with the software you’ve used to program a show. As an example, I performed in 2022 at arts venue Iklectik, also in London, which has a bespoke multi‑speaker setup created by the organisation Amoenus using Max for Live. Working with their in‑house engineer, we decided that rather than reprogram my entire set for the venue, we would use Dante Virtual Soundcard to send speaker signals coming from my virtual L‑ISA Processor in the L‑ISA Studio software out to the front of house for dissemination into their speaker array. This method was used again to drive a 7.1 speaker system in Milan at the Triennale Theatre.

This was a relatively simple solution, but it raises a wider point about future interoperability of systems. Will there ever be a common language or standard for translation between spatial audio software and processors? Many artists release their recorded music immersively using the Dolby Atmos format, but may then have to alter or reprogram for live spatial audio where systems such as L‑ISA Studio by L‑Acoustics or Soundscape by d&b are more often found. In theory, the beauty of object‑based mixing is that it can elegantly translate to any speaker setup, whether that be in a cinema, at home, in a venue or on headphones. As far as I know, however, there is currently no simple way to take a mix from one object‑based immersive format to another.

Outside The Box

Whilst traditional music venues have been relatively cautious about installing immersive systems, other spaces have been a bit more proactive. In London, it seems as though a new immersive space or exhibition appears every week. Some theatres and other cultural venues have been quick to adopt this as a future trend and are responding to changing audience demands. Earlier this year I worked with The Old Market theatre in Brighton, to look at a phased evolution of their layout to present immersive events. Using a modular system of screens plus a number of high‑end projectors they can change their main audience area into a ‘white cube’ space ready for 360‑degree projection and audio. I created an ‘in the round’ version of my show using projection‑mapping to show graphics on all four of the white screen walls. For sound we brought in a 12‑speaker L‑Acoustics system evenly spread around the space, with three speakers mounted at the top of each wall. Beanbags were placed in the space so the audience could be even more involved in the performance.

The programming for this show was interesting and a little challenging, as there was not even a nominal ‘front’ to refer to. I found myself replicating core elements such as kicks and bass on speakers on opposite walls to give a sense of evenness for the fundamentals of beat‑driven tracks. However, it was also possible to be totally experimental with other elements.

Visual designer Freny Antony and I worked together to create bespoke graphics that moved around the four walls of the room, and the sound programming worked in tandem with these to create the illusion of audiovisual objects moving in space. The possibilities of this seem very interesting for future AV shows, and I can imagine that there will be companies working on products that can integrate programming of the two elements together in the future.

As venues such as The Old Market evolve their sound systems to become immersive, there could be a vacuum of content and potentially a requirement for more producers to create in immersive sound for these spaces.

The venue took detailed audience feedback for this event to understand the impact, and again, this was overwhelmingly positive, indicating a strong desire for more similar events. Looking forward, as venues such as The Old Market evolve their sound systems to become immersive, there could be a vacuum of content and potentially a requirement for more producers to create in immersive sound for these spaces.

A 360‑degree immersive show at The Old Market theatre in Brighton, March 2022, with 12 speakers mounted above screens that enclose the entire space.Photo: Chloe Hashemi

A 360‑degree immersive show at The Old Market theatre in Brighton, March 2022, with 12 speakers mounted above screens that enclose the entire space.Photo: Chloe Hashemi

Along the same lines, there are also opportunities emerging in retail environments as brands capitalise on the rise of interest in immersive experiences and look to create ‘activations’ with an element of spatial audio. An interesting space utilising this is The Outernet in London, which is billed as a concept in retail, entertainment and tech and incorporates enormous LED screens and a 70+ multi‑speaker spatial audio system. Passers‑by can stop in and engage with their programme of cultural and brand‑related content.

I was invited to create the sound design for Monolith, a crowd‑reactive piece created by visual designer Jack Dartford and production company Chaos Inc. An immersive L‑Acoustics L‑ISA system was installed in the space, but had not previously been used for its spatial capabilities. It was a very enjoyable experience to create reactive spatial sound on this huge canvas, with the installation reaching over 100,000 passers‑by across the course of a week. The likelihood is that more similar spaces, both fixed and ‘pop‑up’, will emerge as brands enable investment in spatial audio.

A ‘crowd‑reactive’ installation with 70+ loudspeakers at The Outernet, London.Photo: The Outernet

A ‘crowd‑reactive’ installation with 70+ loudspeakers at The Outernet, London.Photo: The Outernet

Space Exploration

As an independent artist, I am still encountering practical challenges when it comes to presenting shows in spatial sound. The limited number of spaces with spatial audio setups means I have to retain the ability to perform in stereo for now, but adoption by venues and practitioners is increasing, and the tools for programming and monitoring spatial audio sets are becoming more accessible. Study programmes on spatial audio are appearing on music production curricula everywhere, and I think this will be a completely familiar format for the next generation of producers.

Overall, I’m excited to see the development of immersive sound, and to enjoy the relatively rule‑free environment where one can pioneer and trial new creative ideas. Whatever the future holds for this tech, it’s something we can all be involved with to shape and create new audience experiences.

Did They Enjoy It?

One of the hardest things to do in evaluating audience feedback is to isolate the influence of spatial audio on their response. Most of the time the impact of the sound, or the way in which sound is delivered, is harder for attendees to articulate than, say, the size of the projector screen, or how the lights are mounted around the room. Sometimes I receive very specific descriptive feedback — I have heard people enthuse about the quality of the sound separation they experienced — but these are quite professionalised terms and often come from those who have worked previously in music production. More usually the feedback is just that “The sound was great!”, or there’s a vague sense of enhancement compared to conventional shows. I also have the impression that the audience feels anticipation and excitement just from the physical presence of speakers all around the auditorium. In the case of the Copeland Gallery, it even seemed to enhance the general aesthetics of the room. It also contributes to the audience’s sense that the show is designed for and around them, and is therefore a different experience from other music events.

Free Space

An immersive metaverse performance with Condense Reality.

An immersive metaverse performance with Condense Reality.

Physical spatial audio setups can be costly, but there are also opportunities for immersive audio where the speakers are not physical at all. Metaverse events have started to become more accessible for independent artists. In February this year I worked with Bristol‑based Condense Reality, which enables content creators to stream live 3D video directly into online platforms to create a metaverse event. This included a volumetric recording of me as the performer with the audience joining as avatars. It was presented as a live binaural mix to the audience. This was an interesting first step for me of uniting a virtual environment with spatial audio. The complete freedom to programme sound here is again quite disorientating, as there is no physical constraint on how and where sound should be placed. In this instance, as it would be received as a binaural mix mainly in headphones, there was a practical consideration to mono and centre bass and kick, allowing other elements to exist in a wider field.

Working with doctoral candidate and researcher Victoria Fucci the resulting assets have been recreated in a VR application for headset use and will be used as a basis to research the effect of audio and visual mixing conditions on emotional experiences for music events in VR. An interesting field of development and one where spatial audio need not present as much of a barrier in terms of cost and setup time.