Rebecca plays cello overdubs, which were captured in Paul's studio using a Lewitt LCT-140 Air mic.

Rebecca plays cello overdubs, which were captured in Paul's studio using a Lewitt LCT-140 Air mic.

Our engineer tracks and comps some piano and vocal performances, before overdubbing both real and sampled string parts.

In this article, I want to discuss a recent recording session with Alice Marple-Horvat and her mother Helen, who co-wrote the two songs we tracked that day, 'Cinnamon Wine' and 'Judas'. The brief seemed simple — I'd record Alice singing and backed by Helen on the acoustic piano, and at a later date we'd add a 'string section' by overdubbing some violin and cello parts. Helen had scored out all the lines in Sibelius, and both songs had similar formats and required similar treatments.

The voice and piano recording was to be done at their family home, so I decided to assemble a simple portable recording system based on my 12-inch MacBook Pro running Logic Pro X and a PreSonus AudioBox audio interface. That would give me up to eight inputs, which would be more than enough. With no 'control room' to speak of, monitoring would be entirely on headphones, and I'd also need to split out headphone feeds for the performers, so I took along my four-output Aphex HeadPod headphone amplifier. As she often records into her own system running an old version of Logic Express, Helen has her own mics and they'd be available to me, but I decided also to take along some of my own so we'd have some options on the day.

Piano

Helen's piano is a well-maintained Bechstein Boudoir Grand Model A dating from 1896, and it takes up most of the space in a downstairs room that adjoins the family kitchen. Several duvets were already hung from a picture rail around the room to help damp any boxy 'small room' acoustics, and Helen had also placed some damping material in the piano itself, around the edges of the piano frame. The lid was propped open. She normally records to an old version of Logic Express using a couple of mics on a stereo bar, but I wanted to try something a little different — I did try a stereo bar at first but couldn't get the mics aimed where I wanted them. Instead, I opted to rig my two Aston Starlight mics as a spaced pair, each on its own stand and suspended in Rycote InVision shockmounts for good measure.

The piano was captured using a spaced pair of capacitor mics, but due to the constraints of the recording space they were much closer than is typical.

The piano was captured using a spaced pair of capacitor mics, but due to the constraints of the recording space they were much closer than is typical.

Classical piano is often recorded with a spaced pair aimed around halfway up the underside of the piano lid, but in this case we didn't have the space to get the mics far enough back to allow this traditional approach. In fact, the mics ended up being quite close to the edge of the piano case. As an experiment, I thought I'd put the mics' in–built alignment lasers to good use by holding a mirror flat under the piano lid, then positioning the mics so that one laser spot fell half way along the bass string section near the hammers and the other half way along the treble strings. I'd never tried this before but on playback the piano sounded very much as I heard it in the room, with a good balance across the strings — and Helen was more than pleased with the result.

Of course, grand pianos are big mechanical monsters, and although this one was well maintained to avoid pedal squeaks and scrapes, the physical action of the dampers nonetheless produced an audible thunk each time the pedal was used. This was particularly evident during the quieter sections because the damper noise doesn't follow playing dynamics. I thought we might just have to live with this as a part of the natural sound produced by the beast, but another spot of experimentation at the mixing stage enabled me to reduce the offending sound significantly, without compromising the basic piano sound. In order to kindle some sense of anticipation, I'll tell you about that when I talk about mixing...

Vocals

Helen decided to play using headphones but, after some experimentation, Alice decided she was more comfortable singing without them. She set up just inside the kitchen area so as to have a clear line of sight to Helen playing the piano, but the kitchen sounded like — well, a kitchen! So we had to improvise some acoustic treatment. A duvet was draped over the fridge-freezer (which was turned off during the recording), a towel hung over a shelving unit, and an Aston Halo screen was set up behind the mic, but rather than have it square-on to the mic, I turned it slightly. That way, Alice could see her lyrics, which also provided more cover against reflections from the kitchen window to her right. To damp down the room and to attenuate reflections coming from behind, we hung a double duvet over a lighting stand behind where Alice was standing.

Alice Marple-Horvat recording vocals, with an Aston Halo screen in front of her and a duvet hanging behind.I set up an Aston Origin cardioid-pattern capacitor mic to try on the vocals, but was greeted by a few low level crackles and pops when I turned up the gain. That's a sure sign of condensation, which often affects capacitor mics brought from a cold place into a warm one — and wasn't a huge surprise here, since I'd left this particular mic in the car overnight! A few minutes warming the mic with a fan heater solved the problem. So, with a mesh pop screen in place, it was time to carry out a few checks.

Alice Marple-Horvat recording vocals, with an Aston Halo screen in front of her and a duvet hanging behind.I set up an Aston Origin cardioid-pattern capacitor mic to try on the vocals, but was greeted by a few low level crackles and pops when I turned up the gain. That's a sure sign of condensation, which often affects capacitor mics brought from a cold place into a warm one — and wasn't a huge surprise here, since I'd left this particular mic in the car overnight! A few minutes warming the mic with a fan heater solved the problem. So, with a mesh pop screen in place, it was time to carry out a few checks.

Despite both the piano and vocals covering a very wide dynamic range, the levels seemed fine and we were getting good-sounding recordings without recourse to EQ or effects at this stage, though I did plan to add a hint of vocal reverb when mixing. Helen didn't want to play to a click track, as there's a lot of ebb and flow in Alice's songs, but she did want a count–in at the appropriate tempo, so I set up Logic to give a one bar count-in. At this point, Alice realised she also needed a count-in — but as she wasn't wearing headphones she couldn't hear it. The solution was to feed the count-in click to a pair of phones placed close to her, so that she could hear it without having to actually wear the phones. This setup gave us negligible vocal spill on the piano mics, but inevitably there was some piano spill getting into the vocal mic, and this was especially noticeable during sections of the songs where Alice sings very quietly. However, it wasn't so much that we couldn't live with it.

Once set up, we recorded two or three complete versions of each song, plus a few extra takes of the more 'challenging' sections in case we needed to do any patching up. In reality every take sounded extremely good, but Alice and Helen knew precisely what they wanted in terms of piano dynamics, timing and vocal phrasing, so several apparently perfect takes were done over until they had what they wanted. Somewhere during this process I realised that rubato actually means 'Don't even think about mentioning a click track!'

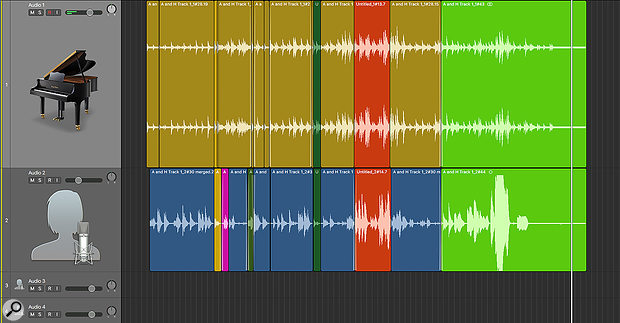

Comping

Before we could add the strings, we needed to comp the final takes, and this wasn't as straightforward as you might imagine because the piano dynamics were sometimes different on the takes that had the best vocals, and so didn't always slot in comfortably. At other times, Helen wanted me to adjust the timing between notes to improve the feel. We soon realised that Helen was navigating by bar number, but as there was no timing grid I could go only by time and waveform shape. To speed up proceedings, Helen jotted down time locations for the various song sections so that we could move around fairly quickly.

The final piano and vocal parts were comped from the best parts of several takes, with some careful edits to get the best from both instruments.

The final piano and vocal parts were comped from the best parts of several takes, with some careful edits to get the best from both instruments.

My strategy was to first group the stereo piano track and mono vocal tracks so that any edits would move both parts together to avoid any sync problems. After identifying the sections that should be replaced, we started from the beginning of the track, auditioned all the alternatives and then dropped the replacement part in place. The 'in' edit was placed initially just before a piano note that fell between vocal phrases, then the section of song following the edit was adjusted until the next piano notes along were in the same position for the insert section and the original recording. A short crossfade just before the piano notes chosen for editing usually worked to avoid any obvious transitions.

However, not all edits were this simple, so after getting the new section in place it was often necessary to ungroup the tracks to allow tweaks to be made independently to the vocal and piano parts. For example, an edit might leave you with two vocal breaths before a phrase, so the 'in' point for the vocals needed adjusting to keep just one breath. For the piano, matching the note positions doesn't always result in a seamless edit, because if the two parts were played with different dynamics, the harmonic overhang from a previous note might change very obviously at the edit point. For that reason, it was often necessary to move the piano edit point one or two notes further back or forward to find the most seamless transition point. But at the same time, I had to avoid the situation in which piano spill in the vocal mic didn't sit correctly under the edited piano. Hitting Save after each successful edit helped avoid problems; you have to maintain concentration when editing this way and make sure the track grouping is turned back on after each edit.

Where timing changes were needed, these were dealt with between vocal phrases, and most of the time Helen only wanted a piano line to start a fraction of a second earlier or later. A simple 'cut and move forward' edit leaves a gap that has to be filled, of course, so my strategy was to drag the start of the inserted region back until it overlapped the section before it, then do a crossfade at the tail end of the decay of the previous note. Where this didn't sound right, I occasionally resorted to time stretching the previous piano note so as to fill the gap.

As you can imagine, doing maybe a dozen edits of this kind in a four minute song takes a while when you're working with free timing rather than a click track, but once complete I rendered each part into a complete new region, so that I couldn't make a mistake further down the line that would leave me with a pile of musical confetti. We've all been there! Of course that should have been the end of the editing, but Helen and Alice took home a rough mix, ostensibly to give the string players something to rehearse to (Helen had all the string parts scored on Sibelius). Naturally, next time we met up they'd found further little things that they wanted to change, either by finding a phrase from an alternate take or making a timing tweak — so that meant a few further edits.

Solving Problems

We had only one technical problem, and almost inevitably that occurred on a loud vocal section that was deemed to be the best performance! It was so loud that there was actually a very brief period of clipping, despite me having left what I thought was around 12dB of headroom when setting up for the recording. Fortunately iZotope's Declipper provided a remedy, leaving us with a clean-sounding part.

After a couple of hours we had versions that they were both happy with — then I found a problem that I really wanted to fix, even though it didn't worry Helen and Alice. The outro of one of the songs was a simple, very quiet piano line, but the noise of the piano dampers being used sounded excessively loud to me — as if somebody were demolishing a shed next door! There were a couple of very definite clunks that simple processing couldn't hide, so I suggested we look at some of the alternative ending takes to see if there was a better one, before I resigned myself to a session of spectral editing. Fortunately we did find a much better ending that had initially been rejected simply because Helen thought one of the piano notes was played too loudly, but after some experimentation with level automation to drop the offending note by a few decibels it was deemed OK.

My catchphrase for the day after tweaking some quite minor things ended up being 'Will it affect sales?' Still, it's always best to have clients who know exactly what they want to hear, especially when, like Helen and Alice, they have the talent needed to put their musical vision into practice.

Once the two parts were set in stone, Alice did a couple of very short vocal overdubs and Helen added a few bars of piano overdub towards the end of one of the songs. She also spotted a missed piano note that she hadn't noticed earlier so we added that as an overdub too.

String Theory

We had to wait a couple of weeks before adding the string parts due to the availability of the players, and the plan was to do all the cello one day and all the violin another. That way, each take would be separate and free of spill, leaving me to take editing liberties when it came to tuning and timing if necessary. In the meantime, we added some MIDI representations of the string parts as a timing guide, and also for possible use in fattening up the live strings if we felt that was needed. We used mainly Logic's own Studio Strings plug-in to provide the sounds. This was a learning curve for Helen, who was used to the feel of a 'real' piano, and she found herself playing some of the notes so gently on my unweighted keyboard that nothing sounded — so I added a velocity boost of 30 to the MIDI input to ensure we always got an audible note. The playing dynamics were too wide for the same reason, so I corrected any notes that were too far off in the grid editor and also reduced the dynamics to 25 percent. Logic's string articulations don't include diminuendos, so where long notes needed to fade out, this was done using volume automation.

A fair amount of time went into balancing the string parts and also automating specific phrases that needed to stand out above the other parts in certain sections.

Strings don't have the defined attack of a piano, and their soft attack tended to put Helen off her timing, so I set up a synth string 'dummy' sound with a faster attack on Logic's Retro Synth for her to use when recording, then switched to the appropriate violin or cello section instrument for playback. She said she felt far more comfortable working that way. To make the string timing feel more natural, I advanced the timing of each track by around 60ms using Logic's track delay parameter, with a negative value so that the softer string attacks felt naturally timed. After a critical listen through, any notes that still felt slightly mis-timed were moved individually until the performance felt right. We couldn't use quantise as the performance was played without a grid, and without any rhythmic instrument present, I didn't trust Logic's auto tempo detection to work on a piano part such as this. We recorded around three violin parts, a couple of cellos and, on one of the tracks, a double bass, which turned out to give us a very good idea of how the finished track might sound. It also let Helen hear how her scored arrangement worked, as this was the first time she'd heard all of the parts playing together.

String Recording

For the cello parts — three on one song and five on the other — Helen's friend Rebecca arrived with her cello, which we set up towards the rear of my one-room studio. I'd been sent a Lewitt LCT 140 Air microphone for review, so I thought I'd try that first — and as it did a perfectly good job, I opted to use it for the recording. It took a few test recordings for me to find the sweet spot for the microphone, but it ended up being aimed more or less at the bridge from around 350mm away. Lower down the body overemphasised the body resonances, whereas moving more towards the fingerboard kept a nice woody tone but lost a bit too much of the low end on deeper notes.

Rebecca read the parts and followed the piano line for timing and got almost everything down in the first take. Just a couple of parts had to be done over, and we did use Logic's Flex Time to massage the timing of a few notes to more closely match the feel of the piano part. Only one note during one of the takes was deemed to be slightly off pitch, and I automated Logic's own auto pitch correction to pull back just that part of the performance. Essentially, the pitch correction was always on but set with a very slow retune speed. Then, when the problem note came along, the retune speed was made faster just for the duration of that note.

Lynette, laying down some violin overdubs.

Lynette, laying down some violin overdubs.

The violin parts were performed by Lynette, another of Helen's friends, with three parts on one of the songs and four on the other. Again, most things went down first take with just a couple of sections redone to tighten up timing issues. This time I used an Aston Stealth dynamic mic in its non-active mode and with its voicing switch set to D (the warmest setting). This isn't a mic I'd tried for strings before so I was curious to see what it could do. It was placed on a stand looking down towards the violin from around 600mm above it and produced a well-defined, woody tone that sat nicely in the mix, so I stuck with it.

After recording there was a little more shifting of note timings using either 'cut and move' or Flex Time, and we also decided to put Logic's pitch correction on each cello part to really nail the intonation on the harmonies. This was slow enough to allow all the nuances to come through but ensured any sustained notes stayed solidly in tune.

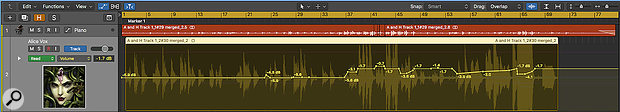

Mixing

Before mixing, the sampled strings (just in case we decided to use them), cello and violin parts were each routed to their own bus; having each section controllable by a single fader would make mixing much easier. I also decided to give each string section a fairly narrow stereo spread, so that I could place the cellos at one side of the mix and the violins at the other. A fair amount of time went into balancing the string parts and also automating specific phrases that needed to stand out above the other parts in certain sections. At the level the strings were finally mixed, I decided that EQ wasn't really necessary so the only processing added was a dash of concert hall reverb.

Given the dynamic style of the vocal, level automation played an important role in the mix.

Given the dynamic style of the vocal, level automation played an important role in the mix.

Aside from a little EQ to soften the sound and some very gentle compression courtesy of the UAD Tube-Tech CL 1B analogue compressor emulation, the piano didn't need much by way of processing. However, the audible piano damper thump was still bothering me in places. I appreciate that the mechanical nature of even a well-maintained grand piano such as this one means some thumping as the damper pedal is released is part of the natural sound of the instrument, and that it tends to be most audible during quieter sections, but I still wanted to reduce it as much as possible without having to resort to lengthy spectral editing. After trying a few of the more obvious approaches, such as multi-band compression and dynamic EQ, I finally settled on iZotope's De-plosive plug-in — this was originally designed to reduce vocal popping, but though it didn't remove the thumps entirely it did reduce them to a much less intrusive level without unduly affecting the basic piano sound.

Despite having dried out the microphone, we discovered some audible low–level noise on the vocal track in the more exposed parts — this had either come from some part of the signal chain or been picked up from some domestic appliance we'd not noticed at the time. The adaptive voice de-noising plug-in that comes as part of the iZotope RX suite took care of this very effectively, without introducing any noticeable side–effects.

Logic's mixer for this project, which shows how the tracks were bused and the various processors and effects deployed in the mix.

Logic's mixer for this project, which shows how the tracks were bused and the various processors and effects deployed in the mix.

Another challenge was to keep the vocal correctly balanced with the piano and strings, as Alice performed these songs with an impressively wide dynamic range, going from barely a whisper to full throttle. To help even out her performance, I used an instance of Waves' Vocal Rider followed by some relatively gentle compression from a UAD 1176, inserted into a bus so that it would come after any level automation. This combination reduced the dynamic range to a useful degree, but without killing the important natural dynamics. That way, modest use of track level automation was all that was needed to keep the vocals in balance with the rest of the track. There was also a slightly shriller edge to one of the louder notes that Alice really belts out towards to the end of one of the songs, so I automated an EQ dip to pull down the stridency just for a couple of seconds. We also employed the Sonnox de-esser on that same track, just to soften some slightly prominent sibilant sounds.

In order to give the instrumental backing something of a classic feel, I set up a reverb send for the piano and instrument mix buses feeding Logic's Space Designer convolution reverb loaded with a concert hall IR. The vocals were treated separately; after auditioning several types of reverb, Alice decided to go with UAD's EMT250 algorithmic reverb, set to a three-second decay time.

On both the songs we recorded, the vocal is doubled in a couple of places by a very short phrase — just two or three words — and this was given a very heady dose of algorithmic reverb from Logic's SilverVerb, to lend it an other-worldly quality. And on the track 'Cinnamon Wine' we added just a hint of the MIDI strings, at maybe 10dB below the main string parts. On 'Judas', we just used the MIDI double bass to beef up the low cello part, and muted the other MIDI strings. To finish off the tracks ready for Alice to put online, I applied some gentle overall bus compression and also used Soundtheory's Gulfoss adaptive EQ, which helps prevent sounds masking each other. Universal Audio's UAD Precision Limiter came at the end of the chain, but with a modest target mix level of -15LUFS it really had very little work to do.

Reader Reaction

After reviewing the finished mixes using the time-honoured process of listening from the next room to try to pick up balance issues, Helen and Alice deemed the mixes complete, and after taking them home reported back that they were extremely pleased with them.

Alice Rose Marple-Horvat: "It was interesting to learn about the many useful tips involved in the recording and mixing of our tracks. Paul was really great to work with, combining patience with encouragement. We feel he brought out the best in us and my mum and I are thrilled with the result."