Here you can see the recording layout for the main band, comprising drum kit, upright bass, piano and sax. The singers and other instrumentalists were isolated in separate rooms.Photo: Daniel Plappert

Here you can see the recording layout for the main band, comprising drum kit, upright bass, piano and sax. The singers and other instrumentalists were isolated in separate rooms.Photo: Daniel Plappert

Working with a band for the first time can be exciting, but a second session provides the opportunity to deliver even better results.

Back in 2015, I wrote a short series of articles about recording, mixing, and mastering a couple of CDs by the band Spektakulatius. The tracking process was fast-moving and a lot of fun, so I was delighted when they recently asked me to get involved in creating their latest seasonal album About Christmas. Of course, one of the great advantages of repeat clients is not having to start with a blank slate at the planning stage, so in this article I'd like to focus on how I updated my recording methods with the benefit of hindsight.

Once More With Feeling

The challenges were much the same as we'd faced before, in that we were building the entire tracking setup on location at a venue I'd never visited before, namely the theatre of a local music school. We had three days to record 14 songs, all in different styles with different band line-ups. The group's four instrumentalists were joined by four singers alternating lead and backing roles, often during the same song, and we wanted to acoustically isolate those vocalists so we could later comp and edit their performances freely between takes.

As before, the need for speed dictated that we record the whole band simultaneously wherever possible, so I chose to capture the four main instrumentalists (sax/clarinet, piano/keyboards, bass, and drum kit) as an ensemble on stage in the theatre auditorium, with the four singers isolated in a separate rehearsal room on the floor above. Previously, I'd brought quieter instruments such as acoustic guitar into my impromptu control room with me to record those without spill, but that had forced me to refine the control-room performer's mic positioning while monitoring over headphones, which never feels very dependable to me. So I resolved this time to find another room I could press into service as an isolation booth for those instruments. Fortunately, adjacent to the theatre's backstage area (my control room in this instance) there was a small storage room that fit the bill nicely.

Expanding The Rig

On the earlier session, my hardware recorder's input restrictions had required me to repatch and submix microphone signals. Since then, though, I'd upgraded to a laptop-based DAW system which effectively doubled my input count. This meant that I could give each mic, DI, or line signal its own exclusive recording input. In the end, I had eight mics on the drum kit; bass and electric guitar DI signals; stereo mic pairs for piano, accordion, acoustic guitar/mandolin, and percussion; a stereo keyboard line signal; and mono mics for upright bass, bass amp, guitar amp, sax/clarinet, flute, and each of the four vocalists. As a result, I could switch between recording different band line-ups very quickly per song, just by choosing which inputs I armed for recording. Mind you, this approach required a lot of mics, mic stands, preamps, and cables, so it was only by pooling resources that the band and I were able to make that happen. For preamps, I'd brought an Audient ASP008 and a Mackie 1642 VLZ3 mixer, and had borrowed a further Audient ASP880, while the band had provided their own Mackie Onyx 1640, giving us ample channels to work with.

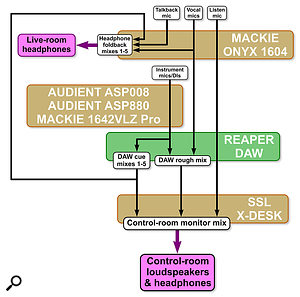

Mike generated six different monitor mixes for the session, incorporating talkback and listen mics and enabling easy auditioning of the different cue mixes from the control room.The foldback monitoring scheme built upon what we'd done before too. We'd previously got along fine with the instrumentalists sharing two mixes and the vocalists sharing another two, but now I had to add a fifth mix to serve the second isolation booth. I was happy to build cue mixes of all the instruments within the DAW, because I was fairly confident that the small latency involved wouldn't interfere with the musicians' ability to perform. With the vocals, however, I was keen to provide zero-latency analogue monitoring, because for some singers even tiny latency delays can adversely effect their pitching. So I preamplified the vocal mic signals through the Mackie Onyx, fed my DAW cue mixes through there too, and then used the analogue mixer's aux sends to feed each of the headphone amplifiers with an appropriate blend of software-monitored instruments, latency-free vocals, and a control-room talkback mic.

Mike generated six different monitor mixes for the session, incorporating talkback and listen mics and enabling easy auditioning of the different cue mixes from the control room.The foldback monitoring scheme built upon what we'd done before too. We'd previously got along fine with the instrumentalists sharing two mixes and the vocalists sharing another two, but now I had to add a fifth mix to serve the second isolation booth. I was happy to build cue mixes of all the instruments within the DAW, because I was fairly confident that the small latency involved wouldn't interfere with the musicians' ability to perform. With the vocals, however, I was keen to provide zero-latency analogue monitoring, because for some singers even tiny latency delays can adversely effect their pitching. So I preamplified the vocal mic signals through the Mackie Onyx, fed my DAW cue mixes through there too, and then used the analogue mixer's aux sends to feed each of the headphone amplifiers with an appropriate blend of software-monitored instruments, latency-free vocals, and a control-room talkback mic.

In addition, I remembered feeling frustrated that I couldn't easily monitor different cue mixes from the control room, so I set up my little SSL X-Desk line mixer as a monitor controller to remedy this, feeding it not only with my main DAW rough mix, but also with the five DAW cue mixes. This allowed me to flip quickly between those different signals using the SSL's channel mute buttons while responding to requests from the musicians for 'more snare' or 'more bass' or whatever.

Miking Adjustments

The main updates to the previous session's drum miking involved moving the kick mic inside the drum.You never really know for sure whether you've recorded something right until you try mixing it, and although the previous session's multitracks had been fairly straightforward to mix, hindsight nevertheless inspired me to make a few refinements to my mic techniques. For instance, while I'd been happy with the way the overheads (a near-coincident pair of Shure KSM141 cardioid condensers) sounded, I'd been overcautious with their internal pad switch settings, such that the raw mic signals ended up noisier than necessary. My original mic choices for the three toms (Avantone CK1 small-diaphragm cardioid condensers) were also retained, although this time I decided to switch in the mic's internal high-pass filter for the upper toms, as I'd ended up doing a similar move pretty much as a matter of course while mixing previously. For the kick, I used my large-diaphragm ADK S7 condenser as before, but having struggled to achieve sufficient rhythmic definition while mixing the rockier numbers on the previous project, I decided to move this inside the drum itself, angling it through the hole in the resonant head using a small mic stand. This also reduced the level of spill on that mic from other band instruments, which had been a concern on the earlier session.

The main updates to the previous session's drum miking involved moving the kick mic inside the drum.You never really know for sure whether you've recorded something right until you try mixing it, and although the previous session's multitracks had been fairly straightforward to mix, hindsight nevertheless inspired me to make a few refinements to my mic techniques. For instance, while I'd been happy with the way the overheads (a near-coincident pair of Shure KSM141 cardioid condensers) sounded, I'd been overcautious with their internal pad switch settings, such that the raw mic signals ended up noisier than necessary. My original mic choices for the three toms (Avantone CK1 small-diaphragm cardioid condensers) were also retained, although this time I decided to switch in the mic's internal high-pass filter for the upper toms, as I'd ended up doing a similar move pretty much as a matter of course while mixing previously. For the kick, I used my large-diaphragm ADK S7 condenser as before, but having struggled to achieve sufficient rhythmic definition while mixing the rockier numbers on the previous project, I decided to move this inside the drum itself, angling it through the hole in the resonant head using a small mic stand. This also reduced the level of spill on that mic from other band instruments, which had been a concern on the earlier session.

Mike also replaced the over-snare close mic with a figure-8 model pointing at the side of the shell.The snare mic that really worked well on the former tracking date was my Superlux R102 ribbon, which I'd placed over the snare and hi-hat at around the drummer's head height, capturing a full and rounded tone for the more laid-back songs. For a more assertive snare sound, however, a Sennheiser e905 cardioid dynamic close mic in the traditional close-miking position had proved less successful, so here again I chose to experiment with an alternative. I'm not a huge fan of the sound of close over-snare mics in general, as they usually seem rather two-dimensional, focusing primarily on stick attack and pitched head resonances. Sure, you can supplement those qualities with an additional mic under the drum, but I figured I'd just try putting my main close mic in a different position instead: alongside the drum where the balance of head resonance, shell tone, and snare noise would be more naturally balanced. The mic I chose was a bright large-diaphragm condenser (AKG's C414B XLII) with its polar pattern set at figure-8 to reject spill from the surrounding cymbals and toms, and this brought us to a much livelier and richer snare sound straight away.

Mike also replaced the over-snare close mic with a figure-8 model pointing at the side of the shell.The snare mic that really worked well on the former tracking date was my Superlux R102 ribbon, which I'd placed over the snare and hi-hat at around the drummer's head height, capturing a full and rounded tone for the more laid-back songs. For a more assertive snare sound, however, a Sennheiser e905 cardioid dynamic close mic in the traditional close-miking position had proved less successful, so here again I chose to experiment with an alternative. I'm not a huge fan of the sound of close over-snare mics in general, as they usually seem rather two-dimensional, focusing primarily on stick attack and pitched head resonances. Sure, you can supplement those qualities with an additional mic under the drum, but I figured I'd just try putting my main close mic in a different position instead: alongside the drum where the balance of head resonance, shell tone, and snare noise would be more naturally balanced. The mic I chose was a bright large-diaphragm condenser (AKG's C414B XLII) with its polar pattern set at figure-8 to reject spill from the surrounding cymbals and toms, and this brought us to a much livelier and richer snare sound straight away.

The mics inside the piano had been large-diaphragm cardioids on the previous session, but this time Mike replaced those with small-diaphragm omnis, which gave a clearer and more natural timbre.For the piano I'd originally used a pair of large-diaphragm cardioid condensers, which worked pretty well on that occasion. However, I've recently been gravitating more towards omnidirectional microphones in this role, on account of their superior low-frequency reach and clearer, more 'holistic' tone (especially when placing the mics inside the instrument to minimise spill from the other band instruments), so I opted for my Oktava MK012 small-diaphragm omni condensers instead. These were spaced about 20cm apart, angled downwards towards the strings from about 15cm away, and splayed by 70 degrees or so to spread their inherent on-axis high-frequency emphasis laterally. Again, this worked out really nicely — where spill from the piano onto other instrument mics had previously been a vital component in the piano's mixdown tone, the omni mics already gave a truer and more natural presentation in isolation. I'd been a little concerned that the omni polar patterns might pick up excessive spill, but this turned out not to be a problem, because we also had more blankets and duvets available to drape over the piano than before!

The mics inside the piano had been large-diaphragm cardioids on the previous session, but this time Mike replaced those with small-diaphragm omnis, which gave a clearer and more natural timbre.For the piano I'd originally used a pair of large-diaphragm cardioid condensers, which worked pretty well on that occasion. However, I've recently been gravitating more towards omnidirectional microphones in this role, on account of their superior low-frequency reach and clearer, more 'holistic' tone (especially when placing the mics inside the instrument to minimise spill from the other band instruments), so I opted for my Oktava MK012 small-diaphragm omni condensers instead. These were spaced about 20cm apart, angled downwards towards the strings from about 15cm away, and splayed by 70 degrees or so to spread their inherent on-axis high-frequency emphasis laterally. Again, this worked out really nicely — where spill from the piano onto other instrument mics had previously been a vital component in the piano's mixdown tone, the omni mics already gave a truer and more natural presentation in isolation. I'd been a little concerned that the omni polar patterns might pick up excessive spill, but this turned out not to be a problem, because we also had more blankets and duvets available to drape over the piano than before!

Baffling Bass Bleed

The biggest headache I encountered while mixing the previous project was the upright bass mic, not on account of its basic timbre, but because of all the spill it was picking up from the piano, drums, and sax in the same room — even though I'd put up some DIY baffling around the player and switched my initial choice of mic for a hypercardioid model. Reluctant to disturb the rhythm-section cohesion by moving the bass player into a separate room, I decided instead to bring some proper mineral-wool acoustic panels with me this time so I could try building a sturdier 'hut' around the instrument on the theatre stage. Frankly, though, my first attempt at doing this was a bit of a duffer! Even with a couple of small mattresses between the bass and drums, two of the acoustic panels and some quilts behind the bassist, and the bass microphone (a Rode K2 large-diaphragm valve mic) switched to hypercardioid, the levels of drum spill in particular were pretty overbearing.

Had the band and I not worked together in the past, it's the kind of thing I might have let slide just to maintain the pace of the session, knowing that I had the instrument's bridge-pickup DI signal to fall back on. Instead, I played the musicians a test recording of the bass microphone, explained my concerns, and asked them to bear with me for half an hour while I built more substantial baffling using further acoustic panels, blankets, and some scenery supports we'd spotted in the backstage area. As I'd hoped, the musicians were very understanding, and in fact they all pitched in with the building process, so it didn't take long before we'd made an appreciable improvement in the spill levels.

Despite this, there was still a lot of spill on that bass mic, so I took one further precaution: the bass player had brought with him the amp he normally used for live gigs, so I set that up behind him and miked that too. On the one hand, I figured this would give a less sterile sound than the DI if I had to supplement the main mic signal in the mix, and on the other hand I also figured it might help the player hear himself more clearly in the room.

More Spill Remedies

Firing the saxophone's bell directly into an sE Electronics Reflexion Filter significantly reduced the levels of spill it generated on other instruments' mics.The sax had also caused me spill problems on the previous Spektakulatius session, because its room sound was bleeding into all the other mics, and that made it difficult to bring sufficiently up front during its solos. The kick mic's inside-the-drum positioning helped, as did the extra blankets we were able to put over the piano. The blankets I'd hung up behind the drum kit and bass must have helped, if only in reducing the overall reverb time in the stage area. However, I did also target the issue at source by asking the saxophonist to aim the bell of his instrument directly into an sE Electronics Reflexion Filter. Although this might seem quite an odd thing to do, it definitely reduced the instrument's projection into the room, and had the ancillary benefit that it provided a stationary target for the player while performing. The thing with sax is that it's often miked up directly on the bell in a live environment, so if you mike it off-axis for recording purposes (which often gives a more well-adjusted tone) many players will instinctively move themselves so that they relocate the mic onto the bell, therefore defeating your mic positioning efforts. Normally I'd use a dummy mic (in addition to the actual mic I'm recording) to combat this tendency, but the Reflexion Filter worked just as well on this session.

Firing the saxophone's bell directly into an sE Electronics Reflexion Filter significantly reduced the levels of spill it generated on other instruments' mics.The sax had also caused me spill problems on the previous Spektakulatius session, because its room sound was bleeding into all the other mics, and that made it difficult to bring sufficiently up front during its solos. The kick mic's inside-the-drum positioning helped, as did the extra blankets we were able to put over the piano. The blankets I'd hung up behind the drum kit and bass must have helped, if only in reducing the overall reverb time in the stage area. However, I did also target the issue at source by asking the saxophonist to aim the bell of his instrument directly into an sE Electronics Reflexion Filter. Although this might seem quite an odd thing to do, it definitely reduced the instrument's projection into the room, and had the ancillary benefit that it provided a stationary target for the player while performing. The thing with sax is that it's often miked up directly on the bell in a live environment, so if you mike it off-axis for recording purposes (which often gives a more well-adjusted tone) many players will instinctively move themselves so that they relocate the mic onto the bell, therefore defeating your mic positioning efforts. Normally I'd use a dummy mic (in addition to the actual mic I'm recording) to combat this tendency, but the Reflexion Filter worked just as well on this session.

I miked up the accordion with a pair of Rode NT5s as part of the main band setup, but this caused no serious spill concerns, because the instrument was only required on a couple of songs that had no drums, and for a couple of overdubs later on. Likewise, recording the acoustic guitars/mandolin (again with NT5s), and flute (with an AKG C414B XLS) in the backstage storage room gave pretty decent separation — at least until a visiting reporter from the local paper decided, mid-take, to sneak out of the control room, through the storage room, and into the main band room without closing the doors properly behind him. Note to future self: remember to gaffer down all bystanders before hitting record!

Mike built a cross-shaped MDF and plexiglass baffle to improve separation between the four vocalists.A couple of the singers on the previous project had ended up sounding a little harsh through the mics we'd chosen then, so I made a point of trying out some other options for the new session. However, my main innovation was in replacing the narrow DIY vocal booth from the previous record's tracking setup with a new home-made screen I'd built from MDF and plexiglass. This looked a bit like a giant revolving door, with each vocalist in one 'V'-shaped section facing inwards towards the others. With the help of several duvets slung behind and above the singers, this not only gave better separation between the voices than we'd had before, but also avoided the boxy timbral resonances normally associated with DIY isolation booths, because each singer only had reflective surfaces around them on two sides, rather than being completely boxed in.

Mike built a cross-shaped MDF and plexiglass baffle to improve separation between the four vocalists.A couple of the singers on the previous project had ended up sounding a little harsh through the mics we'd chosen then, so I made a point of trying out some other options for the new session. However, my main innovation was in replacing the narrow DIY vocal booth from the previous record's tracking setup with a new home-made screen I'd built from MDF and plexiglass. This looked a bit like a giant revolving door, with each vocalist in one 'V'-shaped section facing inwards towards the others. With the help of several duvets slung behind and above the singers, this not only gave better separation between the voices than we'd had before, but also avoided the boxy timbral resonances normally associated with DIY isolation booths, because each singer only had reflective surfaces around them on two sides, rather than being completely boxed in.

Conclusion

In the end, the planning paid off. We got all the tracks in the bag ahead of schedule, and everyone seemed happy with the sounds. Still, there are some things I'd change next time around, I'm sure. For instance, I'd probably try building a proper glazed screen for the bass to get better control over the spill on that mic. That's one of the great things about music recording, though — there's always more you can learn!

Enjoyment Versus Pragmatism

Now, I'm a big fan of trying to capture ensembles all at once, because that usually gets musical-sounding results more quickly, not least because musicians tend to have more fun working that way. Sometimes, though, the most natural performance method doesn't deliver a sufficiently polished end product, in which case you have to weigh up whether to settle for a lesser-quality recording or a less enjoyable recording process.

A case in point on the previous Spektakulatius project was a song the band wanted to do as an unaccompanied eight-voice a capella arrangement. I suggested that the quickest way of doing this would be if everyone stood in a circle around a centrally-placed omni stereo pair, and then I used additional spot mics for the lead, bass, and vocal-percussion parts. My thinking was that this would enable the ensemble to perform naturally, without the complications of headphone foldback, and I could then compile a final recorded performance from the best sections of several takes, much as you might when working in the classical sphere. However, because the band's instrumentalists weren't as accomplished singers, tuning discrepancies made it tricky to get a satisfactory result. I did manage to arrive at a usable final product in the end with a certain amount of editing jiggery-pokery and a touch of Melodyne's polyphonic pitch processing, but it was touch and go whether it'd be up to scratch.

So when, on this latest project, one of the songs featured all the band members singing together, accompanied solely by upright bass, my internal alarm bells began going off. The sheet music only strengthened my reservations, because the male vocal parts frequently maintained an open fifth interval between them, which is (in my long experience as an a capella singer) notoriously difficult to manage for very long without tuning drift. All in all, I felt that a more piecemeal tracking approach would therefore make more sense for this number and, once I'd explained my concerns, the band were happy to follow my advice.

Not that I wanted to build the whole piece painstakingly one track at a time — that would have been overkill. First, I tracked the bass in the main band room, while simultaneously recording the lead soprano melody and its alto harmony voice (mostly moving in parallel thirds, which are a lot easier to tune) in the separate vocal room. Knowing that the pitch of a solo upright bass can be quite difficult to latch onto over headphones, though, I also asked the band's guitarist to strum basic chords on a DI'd guitar in the control room while we were recording, so as to provide a better tuning reference for the singers. The second take hit the nail on the head there, providing plenty of natural musical 'flow', and I subsequently overdubbed the male singers two at a time against that. The result was that I could freely patch any performance errors or tuning problems I wished because there was negligible spill between any of the tracks.

Using A Listen Mic

Overdubbing electric guitar can bring with it communication problems if the player's situated in the live room with a high-gain amp. You see, because the guitar amp is so loud, you need to set the preamp gain quite low to avoid overloading the recording system's A-D converters, and that means you then struggle to hear what the guitarist is saying in the room between takes unless he leans down and shouts into the mic. Sure, you could crank up the monitor level when he's speaking, but you'll then get your ears blown off if he suddenly tries to demonstrate some idea to you by playing it!

On the first session I did with Spektakulatius, we worked around this by shouting a lot and frequently running between the control room and live room, but it was a bit of a pain, so for the more recent session I implemented a 'listen mic' instead. This was a Groove Tubes GT57 large-diaphragm condenser (in omni mode) placed close to the guitarist, so that it picked up a more audible level of his speaking. I then routed that listen mic's signal to the SSL X-Desk I was using to create my control-room monitor mix, and soloed it for communication purposes between takes. Of course, the guitar sound was much more ambient when heard through the listen mic, so I'd unsolo it again whenever I needed to judge the timbre or performance more critically.

Many Hands Make Light Work

My earlier session with Spektakulatius was very much a self-op job, and while I'm well accustomed to working solo, the logistics of such a complex session weren't easy to handle, despite the band helping me out where they could. So I was keen to enlist a bit more assistance this time. Fortunately, my friend and fellow studio owner Herb Felho (www.mixxxster.com) agreed to come along and help me out, as well as lending us some of his own mics (including the Rode K2 we used on upright bass). As a result, I'd estimate we probably halved my normal setup time, not just because 'many hands make light work', but also because Herb could troubleshoot technical gremlins and refine mic positions remotely for me while I listened from the control room.

It's worth noting, though, that pre-session planning is vital to getting the best out of this kind of working relationship. You won't save much session time if you have to spend ages explaining to those helping you what you need done — you need to work as much as possible in parallel. On this project, for instance, I'd already emailed Herb a bunch of my preliminary planning information in advance of the session: a full song list (showing the band and vocal line-up for each number); a table detailing all the mics/DIs, stands, and preamps I was planning to use, which multicore channels they'd feed, and which DAW input those multicore channels would be connected to; a table showing all the cable loom connections needed for setting up all the control-room gear; and an overview sketch of all the audio connections in the recording system as a whole. Armed with those printouts, Herb was able to steam ahead with very little additional instruction, freeing me up to concentrate on live-room setup and mic positioning. I'd also carefully labelled all the pieces of my home-made vocal baffle (which I'd flatpacked for transport), so Herb was able to build that entirely 'in the background' while I was working on the band's instrumental ensemble sound.

Featured This Month

This month's column features the band Spektakulatius, comprising Thomas Göhringer (drums, percussion, vocals), Markus Braun (upright bass, bass guitar), Christian Bolz (guitar, sax, flute), Florian Blau (keyboards, accordion, mandolin), Martina Fritz (vocals), Aysun Idrizi (vocals), Ralf Meiser (vocals), and Christian Steiner (vocals, guitar). Their latest album, About Christmas, is available from their website.

Audio & Video Examples

If you'd like to hear how this project turned out, there is a selection of audio examples on the SOS website at https://sosm.ag/session-notes-0719-media. In addition, I've also posted a special video walkthrough of the whole session setup at www.cambridge-mt.com/youtube.htm, where I guide you through the control room and all three recording rooms to give an overview of how everything was configured.

You can download a ZIP file of hi–res WAV audio examples in the righthand Media sidebar or use the link below.

Download | 133 MB