Rescued this month: Kirsty Cooke.

Rescued this month: Kirsty Cooke.

There are times when a mix engineer needs to do more than just mixing — even if that takes you out of your comfort zone!

Mission creep is a fact of life in mixing. Our job is to generate a finished track that sounds good. If that can only be achieved by editing, pitch and timing correction, replacing sounds or even adding new parts, so be it. The challenge is to know when this additional work is necessary, and to retain enough objectivity to judge whether it’s really helping.

This month’s Mix Rescue was a case in point. Kirsty Cooke had posted several iterations of her song ‘Heydays’ on the SOS Forum, but despite lots of helpful feedback from Forum members, the mix wasn’t quite fulfilling her vision for the track. Realising that potential required a lot of conventional mixing work — but it also meant stepping out of that box.

Imagination

‘Heydays’ is a heartfelt ballad, with Kirsty’s voice backed by piano, strings, synth bass, numerous backing vocal parts and a handful of other elements. She wanted the vocal to be quite forward, “like a solo vocalist in front of a choir in front of an orchestra”, but in her own mix, the backing instruments were too low in level and very reverberant; and although the prominence of the lead vocal highlighted the excellence of the performance, it also brought out loud breaths, sibilants and harshness.

The sophistication of Kirsty’s vocal arrangement was obvious on opening the beautifully organised multitrack. She had exported the backing vocals in named groups, suggesting that they were not intended to form a single choir‑like mass, but distinct parts with their own musical identities. All of them had been generated using her own voice, with artificial harmony generation extending her impressive range even further. The vocals were supplied dry, but the piano recording had rather more reverb baked in than I’d have liked, so my first step was to recreate a new version from the MIDI part.

Kirsty had mentioned John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’ as a point of reference for the piano sound and, slightly to my surprise, I discovered the perfect patch in the free Arturia Analog Lab Lite plug‑in supplied with Pro Tools. This let me vary the hardness of the virtual hammers to dial in an appropriately muted tone. I then put together different impulse responses in HOFA’s IQ‑Reverb V2 until I had something that sounded both intimate and expansive, and turned my attention to the vocals.

The free Arturia Analog Lab Lite plug‑in provided the perfect piano sound for the song.

The free Arturia Analog Lab Lite plug‑in provided the perfect piano sound for the song.

Marginal Gains

Hearing the vocals in isolation made clear that the issues I was noticing in Kirsty’s would need dealing with at source. Given that these parts had been recorded on an AKG D5 — an inexpensive handheld mic — the overall tone was surprisingly good, and there were no issues with background noise or spill. However, some breaths were distractingly loud, and sibilants and ’t’ sounds likewise stood out jarringly, especially when they were duplicated in stacked parts. As is often the case when the singer is moving the mic around, the vocal levels also varied rather unpredictably, with sudden level changes in the middle of notes, or quietly sung notes coming through louder than belted ones.

Clip Gain was used extensively to control levels before the signal hit the Pro Tools mixer. This is just one small group of backing vocal clips!When you have more than 30 vocal tracks to contend with, it’s obviously a massive time‑saver if you can handle these issues using automated tools such as compressors, de‑essers and so on. But in a case like this, where the issues are clearly audible even in the raw tracks, and the level variations aren’t necessarily related to the content of the parts, there is only so much that these tools can do. In other words, you need to roll up your sleeves and get busy with the mouse.

Clip Gain was used extensively to control levels before the signal hit the Pro Tools mixer. This is just one small group of backing vocal clips!When you have more than 30 vocal tracks to contend with, it’s obviously a massive time‑saver if you can handle these issues using automated tools such as compressors, de‑essers and so on. But in a case like this, where the issues are clearly audible even in the raw tracks, and the level variations aren’t necessarily related to the content of the parts, there is only so much that these tools can do. In other words, you need to roll up your sleeves and get busy with the mouse.

There are a few ways to go here, depending on the tools available in your DAW. Since Avid introduced Clip Gain into Pro Tools, my preference has been to start a mix with the faders at zero, and use this feature to adjust the levels of any clips that are inaudible or much too loud. I took this approach further here by making the Clip Gain line visible and using it to write clip‑level automation, aiming to do most of the heavy lifting at the lowest possible level. One benefit of doing it this way is that the height of the on‑screen waveform reflects the adjustments you make, giving you a handy visual guide as to what sort of level to aim for. Another is that it leaves track fader automation available as a second line of defence for fine‑tuning.

Leapwing Audio’s StageOne stereo width plug‑in was used to spread the backing vocals.It will be apparent from the screen captures just how much Clip Gain automation I ended up writing. The total number of automation nodes ran into four figures, and there were places where I re-did it several times. It’s vital to audition the results in context, especially with backing vocals. When there’s a prominent consonant or sibilance in six parts simultaneously, it’s often necessary to make much more drastic moves than you might do in an exposed lead part.

Leapwing Audio’s StageOne stereo width plug‑in was used to spread the backing vocals.It will be apparent from the screen captures just how much Clip Gain automation I ended up writing. The total number of automation nodes ran into four figures, and there were places where I re-did it several times. It’s vital to audition the results in context, especially with backing vocals. When there’s a prominent consonant or sibilance in six parts simultaneously, it’s often necessary to make much more drastic moves than you might do in an exposed lead part.

I also bused each thematic group of backing vocals to its own stereo Aux. As most of them included obviously artificial harmonies anyway, there seemed little point in aiming to have them sound natural. Instead, I decided to try to give each group its own ‘signature sound’. This involved using a different saturation or band‑limiting process on each Aux, but also the creation of separate, deliberately ‘characterful’ reverb treatments. In one case, for example, I fed a rotary speaker emulation from IK’s Mixbox into SoundToys’ Little Plate; elsewhere, I had a lot of fun with the more weird and wonderful IRs from IQ‑Reverb. Finally, reasoning that the centre of the stereo field belonged to the lead vocal, I bused all the backing vocal Auxes to a global Aux where I used Leapwing Audio’s StageOne to spread them as wide as I dared.

The lead vocal needed to sound as natural as possible — and, perversely, this meant doing quite a lot to it!

Leading Role

In contrast to the backing vocals, the lead vocal needed to sound as natural as possible — and, perversely, this meant doing quite a lot to it! Reducing breaths and ‘ess’ sounds in level by exactly the right amount to create the illusion of naturalness is always a delicate balancing act, and I decided this would be achieved most easily by splitting them out to a separate track. Doing this also allows them to be processed differently, which can be handy if for instance you want to use a super‑bright vocal reverb; in this case, though, I bused all the lead elements to a single Aux track to recombine them and apply processing. This included Oeksound’s Spiff plug‑in, which I find to be very effective at attenuating unwanted spittiness and other transient elements.

Achieving a natural lead vocal sound meant splitting problem sounds such as esses and breaths to their own separate tracks.

Achieving a natural lead vocal sound meant splitting problem sounds such as esses and breaths to their own separate tracks.

Conventional EQ is often of limited value on this sort of vocal, because the same treatment that enhances a softly sung verse makes a powerful chorus harsh or brittle. Again, there are several ways you can get around this. You can split the verses and choruses out to separate tracks and apply different treatments. You can automate an EQ plug‑in to apply different settings at different points in the song. Or you can do what I did, which is to use multiband dynamics, in this case FabFilter’s Pro‑MB. I divided the frequency spectrum up into three bands, set so that quiet signals would receive a small gain boost in the midrange and highs, but loud ones would provoke compression in the same regions.

A suitably dark‑sounding lead vocal reverb was derived from Relab’s LX480 Essentials.Reverb is crucial on an exposed ballad vocal, but again, it can be difficult to get right. The treatment needs to give the vocal that all‑important sense of spacious, lavish opulence, but at the same time, it needs to be intimate, as though the singer is standing next to you. The key here is to use plenty of pre‑delay to separate the vocal from the reverberation, and to keep the reverb itself quite dark. This led me to a vintage Lexicon‑style hall algorithm in Relab’s LX480 Essentials, augmented in small doses by a much larger patch from EastWest’s QL Spaces II.

A suitably dark‑sounding lead vocal reverb was derived from Relab’s LX480 Essentials.Reverb is crucial on an exposed ballad vocal, but again, it can be difficult to get right. The treatment needs to give the vocal that all‑important sense of spacious, lavish opulence, but at the same time, it needs to be intimate, as though the singer is standing next to you. The key here is to use plenty of pre‑delay to separate the vocal from the reverberation, and to keep the reverb itself quite dark. This led me to a vintage Lexicon‑style hall algorithm in Relab’s LX480 Essentials, augmented in small doses by a much larger patch from EastWest’s QL Spaces II.

Another thing to bear in mind is that you don’t always want the vocal reverb and other effects to remain static throughout the song. It’s worth looking for opportunities to use delay throws to highlight single words, moments where you might want to ride up or duck the reverb levels, and so on. In the mix of ‘Heydays’ I tried to add a subtle extra dimension to the choruses by bringing in a very short, pitch‑shifted stereo delay.

Keeping the vocal at the right level against the backing required not only the use of a conventional compressor and the aforementioned Clip Gain adjustments, but also plenty of fader automation. The last chorus featured a second lead vocal; this received similar treatment, but with the addition of some stereo spreading from SoundToys’ Microshift to try to keep it out of the way of the first.

Pulling The Strings

At this stage, I had what seemed to me a pretty great‑sounding piano ballad. But whenever I tried to reintegrate the other elements of the arrangement, it just didn’t work. No amount of EQ, reverb or compression seemed to help, and I became convinced that the problem was down to the arrangement. So, with Kirsty’s permission, I hopped across the line that separates mixing and production.

I liked Kirsty’s idea of using a deep, sustained, almost organ‑like sound to fill out the very bottom end of the mix, but her part was perhaps a bit too busy, with occasional wide leaps and staccato notes that just manifested themselves as a momentary loss of low end. This was easily sorted by simply removing any note shorter than a minim, and making sure that the remaining long notes didn’t stray on to the fifth of the chord. A suitably drone‑like bass patch in Sonic Academy’s well‑equipped ANA 2 completed the job.

The string arrangement was rather more challenging! Kirsty’s original arrangement featured just viola and cello, with no violins. The cello part contained two lines, with a lot of thirds and other closely spaced intervals that wouldn’t usually be found in the nether regions of a string arrangement. These congested lower registers, combined with a general lack of motion, meant that it had a tendency to disappear into and muddy the mix.

Rather than use Kirsty’s original as a template, I decided to see if I could write a completely new arrangement. What was needed, I decided, was not a full symphonic string section, but a more intimate chamber ensemble. Spitfire Audio advised that their Chamber Strings should be perfect, and so it proved.

Spitfire Audio’s Chamber Strings offered an intimate string sound which was just right for the song.

Spitfire Audio’s Chamber Strings offered an intimate string sound which was just right for the song.

My first step was to bounce out the existing vocal‑and‑piano mix and load it into a new Pro Tools session, allowing me to lower the buffer size in order to play string parts from a keyboard without noticeable latency. Then, I worked out the chords from the piano part and wrote them to the Chord track in Pro Tools. This revealed a slightly unusual song structure, with a bridge section that appeared only after the first verse, and a restless chord sequence in the chorus. Each chorus was preceded by the dominant chord of Bb; however, instead of resolving immediately to Eb, the chorus began on the subdominant, and only visited the tonic chord in passing before working its way back to the dominant again.

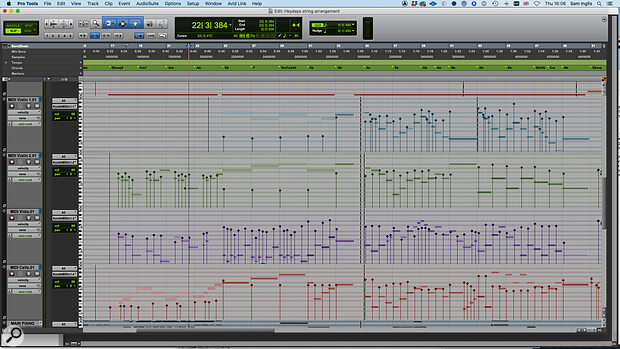

The string arrangement was drafted in a separate Pro Tools session, with the Chord track (top) providing a helpful reference.

The string arrangement was drafted in a separate Pro Tools session, with the Chord track (top) providing a helpful reference.

A Bluffer’s Guide To String Arranging

With the vocal melody more or less internalised through repeated playing, and the chords laid out in front of me, I worked through the song in sections, sketching out and refining ideas. I am no Igor Stravinsky, so any attempt on my part to compose anything of this sort takes a long time, involves a lot of trial and error, and generally results in quite a bit of cursing. What follows should be taken as the lessons of bitter experience rather than formal training or theoretical correctness! With that in mind, here are a few thoughts that might be helpful to anyone in a similar position:

- Less is more. Don’t feel that every bar must have string action, or that all the instruments need to be playing all the time. Solo lines or two‑part harmonies can be very effective, especially if they’re juxtaposed with denser arrangement elsewhere.

- Rather than just playing block chords to reinforce the harmony, try to think of melodic or motivic ideas that mirror or answer what’s going on in other parts. These can always be simplified if they get too busy.

- Don’t be lazy. Once you’ve come up with an arrangement that works for the first verse or chorus, don’t automatically copy and paste it to the others. Think about how it might be varied, extended or built on to take the listener on a journey through the song.

- If you’re struggling to get started, begin with the outer parts — usually the first violins and the cellos — and fill in the inner parts later.

- Whilst you don’t need to follow all the ‘rules’ of harmony in order to produce an effective arrangement, it’s worth knowing some of the most important ones. They are rules because, by and large, the things they prohibit tend to sound bad! So, in general, it’s desirable to avoid parallel fifths and octaves; don’t use chords in the second inversion except under very specific circumstances; aim for wide spacings between the lowest parts and closer ones in the upper parts; and if there's any doubt about which note of a chord to double, the root is usually the safest bet.

- Any good string library will include different articulations such as pizzicato, marcato, staccato and so on, which can be selected using keyswitches — low notes on the keyboard that are below the range of the actual instruments. Used judiciously, these can add interest, life and realism to your arrangement. Used injudiciously, they can sound like a complete mess. The more exotic ones should be avoided unless you really know what you’re doing!

- String sounds take time to ‘speak’. In MIDI terms, this means that hard‑quantised notes will often sound late. Go with what sounds right, not what looks right.

- Be open minded to the possibility that the ideas you come up with on a MIDI keyboard might actually work better with other sounds, not just strings.

Putting it All Together

To my mind, the ideal string arrangement is one that adds melodic and harmonic interest to the song whilst supporting, rather than overshadowing, the other elements. Several times I found my own attempts yo‑yoing between ‘boring’ and ‘fusy’, and it took plenty of MIDI editing to prune them to a reasonably happy medium. I tried to reinforce the dynamics of the song by using soft, staccato sounds in the quieter choruses, and switching to legato for the more dramatic choruses. I even sneaked in a bar of trills at the end of the bridge.

Whatever its musical merits, or otherwise, the new arrangement at least made life easier from a mix point of view. With fewer notes crammed into the congested area below Middle C, it didn’t clog up the low midrange; and its more melodic, mobile nature helped it stand out even at a fairly low level. It didn’t hurt that Spitfire’s Chamber Strings sounds great, too.

Nevertheless, fitting everything together was still a challenge, and there was a tendency for other elements to fight with the lead vocal for attention during the chorus. To keep the lead vocal in its rightful position — in front of the mix, but not so much so as to make the rest of the track sound small — I routed all the backing vocals and all the instruments to stereo Auxes, so I could use the vocal as a trigger to duck them.

Ducking in action: the upper‑mid band is keyed from the external side‑chain input, named ‘LV Limit Out’, with a heavily limited version of the lead vocal.

Ducking in action: the upper‑mid band is keyed from the external side‑chain input, named ‘LV Limit Out’, with a heavily limited version of the lead vocal.

The most basic way to set up ducking is to place a compressor across the backing Aux and send directly from the vocal to its side‑chain input. The problem with this is that you get more ducking when the vocal is loud, and less or none when the vocal is quiet — yet it’s the loudest sections of the vocal that need less help from ducking. To counteract this tendency, I sent from the vocal to a separate mono Aux, used a limiter plug‑in to completely flatline it, and then sent that signal to the compressor side‑chain. This makes it easy to achieve a consistent amount of gain reduction. Rather than using a conventional compressor on the instrument Aux, I used another instance of FabFilter's Pro‑MB to target the upper midrange where things needed to be kept particularly clear for the vocals. There was also a whole lot more compression going on on the mix bus than I’d normally be comfortable with, but that seemed the best way to achieve the sense that everything else was present, yet behind the voice.

Some songs invite you to throw the kitchen sink at them, and I did consider adding drums or electric guitars too. ‘Heydays’ is certainly strong enough to stand the treatment, but by this point it was working pretty well in its current incarnation, and I decided that I’d stepped far enough beyond the remit of the mix engineer already. The problem with mission creep is that, unless you keep a firm watch on it, it never stops!

The Perils Of Doubling

One thing that puzzled me about Kirsty’s own mix of ‘Heydays’ was a sudden huge jump in the level of the lead vocal, about a minute in. Opening the multitrack revealed a not uncommon problem in mixing. To try to give the vocal a stereo spread, she had duplicated it and panned the copies hard left and right; but unless these duplicates are shifted in time or pitch, they’ll simply recombine with the original part to give a louder mono vocal. To achieve any sense of width, the duplicates need to be processed to make them different from the main part, and each other.

Rescued This Month

Kirsty Cooke is a solo songwriter, vocalist and producer based in Somerset, UK. Her writing style varies depending on the message she needs to convey in her music, fluctuating from electronic pop and trip‑hop styles through to more cinematic emotional songs such as ‘Heydays’, hence taking on an eclectic mix of references during writing.

Kirsty spent three years studying Digital Music at Brighton University back in 2004 where she discovered her love of music for film and soundtrack, and tries to draw this type of emotion into her music. She releases independently and you can listen on all streaming platforms. ‘Heydays’ will be available to stream and download on all platforms from 20 August 2021.

Remix Reaction

“I could hear in my head exactly how I wanted the song to sound: big, emotive but well balanced. I sought advice on the SOS Forum as the mix was sounding muddy and unbalanced. I wanted my vocal to stand out, but it was overpowering the instrumentation as well as the backing vocals drowning each other out. I got a to a point where I managed to mix the vocals to a better standard, however the main vocal was always far too loud during the chorus after mixdown when I attempted to double the track and give it some stereo width. On top of this the instrumentation was dwarfed by the many vocal backing tracks during chorus sections and I struggled getting the levels to sit right without peaking it despite spending many hours playing with automation, EQ and plug‑ins.

“When Sam offered to assist with the mixing and string arrangement, I was excited to see what he could come up with. I can’t lie, I was a blubbering wreck when I first listened to his new arrangement/mix as it just sounded so emotive and beautiful, with big cinematic movements that are utterly captivating. When I originally wrote the song it was going to be a piano and vocal piece only, but it just didn’t seem up to par with the lyrical content, hence I added cello, bass and viola to fatten it up, but there was a certain edge missing.

“My original mix didn’t accommodate the lower frequencies enough to give a very rich sound, my piano was especially lacking in the low end. I mentioned to Sam I loved the piano timbre in John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’ and I think he did a fantastic job of emulating this, which is really very special for me as ‘Imagine’ was a song that my father loved and this song was written for him.

“The addition of the string arrangement Sam added has really helped all those vocal parts to slot into place without overpowering the instruments. The track still feels vocally led but now has that ‘big fat’ sound with the nicely balanced ‘big notes’ that I heard originally in my head. I had mentioned to Sam that I like the build‑ups and big orchestral sounds of Florence Welch and he has delivered beautifully on all these references. Thank you, Sam for bringing this song up to its potential, you have done a wonderful job!”

Hear For Yourself

Audio examples and brief notes to accompany this article can be heard by visiting https://sosm.ag/mix-rescue-1021 or downloading the ZIP file and auditioning the hi-res WAV files in your own DAW.

![]() mix-rescue-kirsty-cooke-audio-1021.zip

mix-rescue-kirsty-cooke-audio-1021.zip