Mixed this month: Cambridge–based band Fred’s House.

Mixed this month: Cambridge–based band Fred’s House.

Fred’s House: Our engineer overcomes lashings of speaker bleed as he massages a vocal–heavy mix into shape.

You might remember this month’s band, Fred’s House, from the recent feature about tracking vocals in the control room without headphones (http://sosm.ag/voxnoheadphones) — they kindly provided the vocals for our test sessions. This time, I want to write about mixing their track ‘Ghost Town’, which I’d recorded before those test sessions in a similar fashion — that’s to say, without headphones, monitoring via the speakers in my control room — in an attempt to help the vocalists inject a little more energy into their performances. However, these sessions were one of the reasons we’d been keen to test the phase–cancellation techniques away from the pressure of a real session — the recordings suffered with rather more bleed from the speaker playback than was ideal!

‘Ghost Town’ is a particularly vocal–heavy track, with three–part harmony sections in the chorus and dual lead vocals for most of the song, which meant that there was plenty of bleed to deal with come mixdown. How would having that much vocal bleed affect the mix process? And would the finished mix generally be able to keep that live feel, whilst still having enough polish and presence to stand up on radio and modern playback systems?

Getting Started

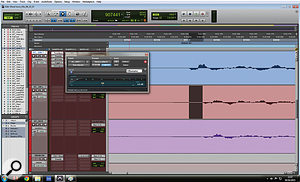

I’ve very recently returned to using Pro Tools as my primary DAW after a few years away, and have slowly been re–acquainting myself with some of its house–keeping features. Although general templates can be useful starting points, I always like to spend a little time tailoring each session to the specific song — it just makes it easier to work on a mix when the creative juices get going. This preparation involves stacking the tracks in an order that makes sense to me, colour-coding and sectioning off key areas into groups. I’ll also create aux tracks for sub mixes and perhaps three or four effects sends. As well as speeding things up and helping with project navigation, my goal here is to be able to get quite quickly to a point where I can work on shaping a mix using as few elements as possible. Unlike some monster pop projects you see, with hundreds of tracks, most of the stuff I work on will have somewhere in the region of 30–40 tracks and even then I’ll usually train my focus primarily on six to 10 critical elements for about the last quarter of the time I spend mixing. The fully prepped Pro Tools session, with groups, colour-coding, aux channels and markers, to help speed up the mix process.

The fully prepped Pro Tools session, with groups, colour-coding, aux channels and markers, to help speed up the mix process.

Fast & Fresh

With everything laid out in this fashion, I worked quickly to get a rough balance of the song using nothing but the level faders and some panning. If the song is good and has been recorded reasonably well, this process should give you an enjoyable half an hour or so — it’s a unique time during which your ears hear a track in a fresh and fairly objective light; the minute you start wheeling out the plug–ins this changes. At this stage, then, it’s worth actively thinking about what you feel are the key elements to enhance (or hide!), developing a broad idea of where you might like to take the track, and storing away a few ideas for adding excitement and interest that you can come back to later in the mix.

Included in this particular arrangement was a full drum kit, with close, stereo overhead and mono room mics, DI’d bass guitar, one electric rhythm guitar part, a solo acoustic guitar with a few mic options, some keyboard pads, group claps and tambourine parts, and several lead and backing vocals. Although the result of my 20–30 minutes’ work sounded a little dull and flat when judged by final–mix standards, I was able to build a pretty decent balance of the track, as well as having 3–4 ideas tucked away for things to try later on. I also decided that the drums and those all–important vocals would need the most initial work.

Drums

As a mix engineer, I really wanted to get to the vocals as soon as possible but, being a drummer too, I felt a real need to get the drums sounding half decent fairly swiftly, so I started work with them. The raw drum sound was actually pretty good, but there was quite a strong build-up of low–mid frequencies (around 200–350 Hz) and a slightly dull ‘papery’ feel that I suspected was due mostly to the somewhat ancient batter head on the snare drum. I was keen for the drum sound to reflect the overall aesthetic of the track, which meant that although I wanted to add some polish and punch, I also wanted to retain the nice sense of energy and live performance.

I have a few different ways of approaching drum mixing, my choice typically being determined by the sound of the overhead mics. Sometimes, it’s a damage–limitation job, but for this track, once I’d removed some low frequencies, I felt I had a nice general picture of the kit and that I’d be able to flesh this out with the other mics. This fleshing out, or ‘building against the overheads’, as I call it, requires a little patience and a methodical approach, checking the phase relationship of each mic with the overheads, ensuring the close mics are working as well as they can to support the natural sound of the kit.

Pro Tools’ Time Adjuster offers an easy way to compensate for timing differences in multi-miked drums.

Pro Tools’ Time Adjuster offers an easy way to compensate for timing differences in multi-miked drums.

I find that monitoring in mono (see the Mono As A Mix Tool box) is really helpful at this formative stage, as it gives a much more pronounced result when comparing phase relationships. So, working in mono, I first checked the phase relationship was good between the left and right overhead mics before moving on to listen for improvements when the polarity of each close mic in turn was inverted. This can often produce quite dramatic changes but it can also be quite subtle, with the preference being a subjective question of taste and general mix tonality. In the latter case, it’s worth taking time to decide on your preference because the right choice can mean you ask far less of your EQ plug–ins.

I chose what I thought gave me the best results and moved on to see if I could gain any extra ‘tightness’ and ‘punch’ by adjusting the time relationships between the mics. One of the things I’m enjoying about returning to Pro Tools is the ability to use the cursor to highlight and give a sample-accurate reading of the distance between the beginning of drum transients on different channels. Looking at the close mic channel for the snare drum I could quickly work out that the snare drum was hitting the close mic 91 samples sooner than it did the overhead mics and could thus line them up via the ‘time adjuster’ plug–in. It doesn’t always work conclusively, but in this case I was able to extract a nice bit of extra fullness from the snare and tom mics with minimum fuss. I was also able to remove a little flabbiness from the kick drum that I’d noticed while setting up the rough balance. You can of course achieve the same thing by dragging the audio tracks in line with each other by eye, but I love how easy it is to undo and audition the processing at various points in the mix.Remaining in mono for the moment, I began to do some subtractive EQ on various elements of the kit. To counter the aforementioned build-up of low–mid frequencies, I removed varying amounts around 200 to 400Hz from the kick, snare and overhead mics until I was happy that the drum sound had a bit more clarity.

With this basic work done, it was time to free myself from the confines of mono monitoring and listen to what was going on in stereo. Assuming all is well, this is usually a nice, refreshing and sometimes inspiring moment — the sound opens out beautifully. Before moving on, though, I wanted to make the drums a bit more ‘real world’, which I did by brightening the snare a little (with some EQ in the 2–5 kHz region) before applying some subtle parallel compression on the whole drum kit. I’d fine tune this later, alongside some other processing.

The Murky World Of Vocals

I had three double–tracked vocal parts to play with and these were, in relation to the male lead vocal, broadly low, mid and high harmony parts that came in during the choruses. All three vocalists in the band sing in quite different styles, so my main challenge was to create a nice blend at the right times whilst managing the interplay between the different vocal styles. As I mentioned, all the vocals had been recorded in the control room with the cue mix coming over the speakers, and the recordings suffered from a fair amount of bleed. I normally wouldn’t be hugely concerned about a little speaker spill, but as I had literally six layers of bleed to contend with at times, I wanted to see what effect this was having on the overall tone and feel of the mix.

Some spill was removed from the backing vocal parts using Pro Tools’ Strip Silence tool.

Some spill was removed from the backing vocal parts using Pro Tools’ Strip Silence tool.

Where bleed is a problem, it’s best dealt with at source, and if you’ve not read it yet, I’d urge you to read the recent article in which I describe ways to record in front of the speakers while minimising bleed. That wasn’t an option here so, with all the vocals set up as a group in Pro Tools, I quickly muted and un–muted all the vocals to see what effect it was having. It wasn’t catastrophic by any means, but it was definitely adding a bit too much ‘murkiness’ to the mix and it seemed to ‘smear’ the kick and snare drum sounds in particular. Applying a broad low–cut filter at around 85Hz on all the vocals helped quite a bit straight off the bat. Bizarrely, after a little experimenting, I decided that I actually quite liked the sonic effect of the bleed when one or two of the vocals were playing! Still, I would need to do something to reduce the impact on some of the other channels.

Leaving the male and female lead parts alone, I cleaned out all the spill between phrases on the double tracks and backing vocals with the Strip Silence tool in Pro Tools, taking care to tweak the start and end ‘pads’ to ensure that the results sounded as natural as possible. This worked pretty well, as the main bulk of the vocals entered during the chorus — any subtle changes in feel were lost in the crowd. The panning and balance settings I’d established during my rough ‘faders up’ mix seemed to be holding up well at this stage. I had the male lead vocal slap bang in the centre and its double track tucked underneath. This was flanked by doubled male falsetto-type parts either side at about 45 degrees and the female ‘mid’ vocals, which I’d panned hard left and right.

Softube’s TSAR–1R plug–in was used to provide a ‘chamber’ reverb for the vocals.

Softube’s TSAR–1R plug–in was used to provide a ‘chamber’ reverb for the vocals.

One problem I find when vocal recordings have spill, or more general ‘room’ sound for that matter, is that it can be tricky to optimise your vocal effects. This is the reason most people go to so much trouble to record dry vocals — it creates a nice, clean canvas on which to paint your effects. It’s not an insurmountable problem but I do always find myself having to work that bit harder to get vocals and their effects to ‘sit’ nicely in the mix, especially with the all–important lead vocal. Another, perhaps more obvious, pitfall is the effect that dynamics processing has on proceedings: that small amount of spill quickly becomes an annoying amount of spill when typical vocal compression is applied!

With this in mind, I kept the amount of compression fairly modest by modern standards, the idea being that I might have to do more riding of levels a bit later on. I normally like to keep things quite simple reverb–wise, but it was proving hard to find any kind of plate, room or spring sounds that I liked, even remotely. After endless auditioning and tweaking, I eventually found a nice short chamber effect courtesy of Softube’s TSAR–1R plug–in. This worked well when applied liberally on the two other vocals, but for the male lead I was only able to use a very small amount before it started to feel ‘detached’ from the music again, especially during the more exposed verse sections. By this point, I’d spent quite some time on the vocals and they were sitting well in the chorus sections. I knew the verse needed a little more work, but it felt sensible to park that issue for the time being, and devote some energy to other elements of the track. Sometimes just coming back to a problem later is all that’s needed, and I hoped that would be the case here!

The kick drum and bass guitar both had a lot of energy around 110Hz. Removing some of this build-up in this region on the kick drum helped them sit together better.

The kick drum and bass guitar both had a lot of energy around 110Hz. Removing some of this build-up in this region on the kick drum helped them sit together better.Bass & Guitars

Listening to the bass guitar, although it was nicely played and quite tight with the drums, it was a very busy part. There was little I could do about the choice of part but a quick check with the excellent Fabfliter EQ plug–in confirmed what I suspected, in that there was quite a large frequency build-up around the same area as the kick drum. Getting the right blend of unity and separation between the kick and the bass is a key part of many a mix and I set about trying to achieve this. Deciding the kick drum better suited holding the real low frequencies I used a high–pass filter to remove most of what existed below 50Hz on the bass. I removed a notch just below 110Hz on the kick drum to allow the bass to own that area, which is where the main clash was occurring, and then I used the old trick of side–chaining a compressor to duck the level of the bass a little on every kick drum. This was subtle but I liked the little bit of glue it seemed to add to the two parts and the combination of these two processes seemed to work nicely. A compressor was used on the bass guitar, but with the input keyed to the kick drum. This helped add a little glue to the low–frequency parts.

A compressor was used on the bass guitar, but with the input keyed to the kick drum. This helped add a little glue to the low–frequency parts.

For the electric and acoustic guitars things were reasonably straightforward. I’d initially panned them to opposite sides in my rough balance and I was keen to keep this sense of width, whilst also keeping the middle of the mix nice and clear. The only real hitch was that the acoustic wasn’t quite tight enough — or important enough to the track — to be made as loud as the electric. My solution to this was to ‘tuck the acoustic in’ a little, both in terms of volume and panning, the result being that it was fairly quiet and more textural. Keeping the Electric guitar out wide on the left, I then sent some of it to a spring reverb via a send. I hard panned this effects return to the opposite side. After carefully checking that nothing strange happened in mono, I was happy that this had the effect of balancing out the sides of the mix whilst also adding a nice bit of space around the electric guitar part. After some very basic brightening EQ, the final touch was to add a ‘spooky’ sort of effect — as requested by the band — which I did using the Soundtoys ‘Tremolator’ on the solo part. A spring reverb was used on the electric guitar, and the effect return panned to the other side of the mix.

A spring reverb was used on the electric guitar, and the effect return panned to the other side of the mix. Soundtoys’ Tremolator plug–in was used to add a ‘spooky’ effect to the guitar solo.

Soundtoys’ Tremolator plug–in was used to add a ‘spooky’ effect to the guitar solo.

Checks & Balances

In terms of mixing, it’s an interesting time for me at the moment. After several years of working in the same room with a familiar setup, I’m now working in a new room, with new monitors and less familiar DAW software. It’s been a testing but also enjoyable ‘reboot’. In learning a new room, I’ve made much more of a point of testing my mixes outside of the studio and I now have a routine of sorts that, depending on how much time I have to do that, seems to be working quite well. I like to do the usual checks in the car, on a small stereo at home and over headphones and so on, but I don’t find it 100 percent helpful to do so immediately after listening on studio monitors. I find that too much contrast displeases my ears and makes it hard to be objective, so I like to leave at least an hour or so (but ideally until the next day) before checking how things are translating in the ‘real’ world. When I return for the second, and hopefully last, round of mixing I try to work in very short focused bursts, being careful that I don’t allow my ears to settle and get too accustomed to the things I’m trying to improve.

The final EQ used on the lead vocal.

The final EQ used on the lead vocal.Pulling Things Together

In the case of this mix, and returning the next day after a few of the described checks, there were just two or three key areas that I was keen to work on. The general balance felt good but the main issue was that the lead vocal felt a bit detached. I was also keen for the whole mix to have a more defined, brighter sound. Tackling the lead vocal first, a simple dip in level helped and I got a bit more surgical with the FabFilter EQ than I normally would on a lead vocal, to give it a little more definition. With this done, a short 64ms echo delay from SoundToys Echoboy seemed to work better than the reverb: it gave the vocal just a little ‘wrapping’ to help it sit in the mix.

To add some useful clarity to the drums, EQ was used on the stereo drum bus, along with Noveltech’s Character plug–in.

To add some useful clarity to the drums, EQ was used on the stereo drum bus, along with Noveltech’s Character plug–in.When working on the overall tonality of a mix it’s easy to get dragged down the path of trying to make everything brighter. In the case of the ‘Ghost Town’ mix, although I was applying a high–shelving EQ on my mix bus, it felt more that their were some areas of the frequency spectrum where parts were masking one another, and that the track felt a bit ‘frumpy’ in the low mid–range area. I made a mental note of a few areas I could work on to try and address this, the first being the bass guitar. The guitar parts were quite passive–sounding, so the bass guitar needed to have a strong presence. With this in mind, I boosted some of the higher frequencies of the bass (up to around 2kHz) quite dramatically, making it more audible and thus allowing me to bring the bass down in level as a whole. My next step was to remove a bit of flab around the drum kit, using an EQ on the drum bus. This involved a little notch around 360Hz, which allowed me also to raise the bottom end with a little bump around 50Hz. As a final touch on the drums, I used the Noveltech Character plug–in, which slightly mysteriously claims to ‘enhance natural elements’ of a source. I’m not sure about that phrase, but it certainly added a nice sense of ‘forwardness’ to the kit, but without making the cymbals sound too harsh.

Whilst making these alterations I was also tweaking my mix–bus EQ to help get the final result I was looking for. After a little work on some individual mid–range elements, I applied some shelving EQ boost to both ends of the spectrum using the mix EQ. This final stage of mixing really requires that you have a high–quality monitoring setup, and you might think that it sounds rather like mastering. That’s true to a certain extent, but you, unlike a mastering engineer, have the luxury of being able to dip back into the mix to adjust things, which makes the process well worth going through. A good example of its worth is that I really liked what the high shelving EQ was doing to the mix, except what it did to the cymbals. As the mix was still ‘live’, I was able to go to my drum overhead tracks and take a little top end off to compensate. The final stage of the mix involved EQ’ing the mix bus, as well as fine-tuning individual channels.

The final stage of the mix involved EQ’ing the mix bus, as well as fine-tuning individual channels.

Summing Up

I felt like I met my objectives for this mix in the end, but I certainly had to work quite hard with a few areas. Aside from trying to manage the live/polished balance, the main issues were the layers of vocals that I’d recorded in a slightly unconventional manner. Although I’ve witnessed the benefits of recording vocals with speaker spill, it’s perhaps not ideal to have multiple vocal tracks recorded in this way. I could certainly have benefited from using phase–cancellation techniques to remove spill, had that been available for this mix. It’s all about the result, though, and while I had to be a bit more heavy handed with EQ than I typically like to on vocals, the spill actually helped me keep a little energy throughout and I was pleased at where things ended up. The band’s reaction was really positive and they were really pleased with how all the different vocal parts could be heard and that I’d managed to keep their precious live feel intact — so I must have got something right!

Mono As A Mix Tool

It’s still worth worrying about how your final mix works in mono, with the main concern for me being the small one–speaker DAB radios many people seem to use. The most common symptom of mixes going wrong in mono are when key stereo elements are dramatically reduced in volume or become dull–sounding. I can live with the cymbals and backing vocals seeming a little quiet, but if you’ve applied any pseudo–stereo processing (particularly Haas delays), without checking for phase cancellation, you might be in for a bit of a shock — things can literally disappear. I also find listening in mono very useful early on in the mix, to check phase coherence on different drum mics and to get a clearer idea of what frequencies of one instrument might be trampling on another. A good tip — after you’ve hit your mono button on your interface or mixer — is to switch one of your speakers off. This avoids the ‘fake centre’ effect you get from listening in mono through a stereo speaker setup, though you might find that you want to raise the level to compensate while monitoring like this. A better option is to have a dedicated single speaker, which can be matched to your reference level — that’s one reason for the popularity of single Auratones, Avantone Mix Cubes and the like.

Mix-bus Compression

It’s easy to misuse a compressor that’s operating on your whole mix, and it’s important to think about at what point you begin to use it. You can insert it towards the end of the process, in which case it will act almost as a kind of mastering tool, or use it earlier on, in which case it will be a fundamental ‘shaper’ of your mix. For ‘Ghost Town’ I chose to use the Slate Digital FG–RED mix-bus compressor early on, shortly after I began to go more in depth with the drums. I’d set the basic levels for the whole track by this point, so I had enough of a starting point to decide on basic settings and to be able to choose a ‘flavour’ of compression. Using it this early means you’re mixing into the compressor from there on in, but do remember it’s there, and that the key to getting this technique to work is that a little goes a long way!

Audio Examples Online

We’ve placed a number of audio examples from this session on the SOS web site for you to listen to at your leisure.