The edits in the two guitar tracks at the top of this screen are obvious, but the real problem is with the double bass in the lower half of the screen. Here an edit has been rendered without fades or backfilling, meaning the waveform suddenly cuts off and gives way to digital silence.

The edits in the two guitar tracks at the top of this screen are obvious, but the real problem is with the double bass in the lower half of the screen. Here an edit has been rendered without fades or backfilling, meaning the waveform suddenly cuts off and gives way to digital silence.

Bands are still recording music even though they can’t use professional studios or play together — and this means new challenges for mix engineers.

The Covid crisis has prompted lots of musicians to get stuck into home recording. As a result, many mix engineers have been tasked with bringing order to unruly lockdown projects! Every mix bring its own challenges, but current circumstances often introduce particular issues. In this article, I’m going to look at some ways of dealing with these, with the help of well‑known Cambridge musician Nick Barraclough.

Nick went into lockdown with a brand‑new copy of Pro Tools, some great songs and a bulging contact book. In most cases, he began by recording his own parts: electric or acoustic guitar, vocals, and sometimes double-bass. He then sent the skeleton tracks to collaborators, before stitching together everyone’s contributions. As Nick describes it: “Contributors’ technical abilities ranged from those far more adept than me with studios, to those whom I had to supply with recorder, mics and even headphones! Some said they missed the buzz of live collaboration. Others said they appreciated the opportunity to get their part right, in their own time, without the presence of others pressurising them.”

From the point of view of the mix engineer — me — that meant a starting point rather different from a conventional studio‑recorded session. Some of the musicians had recorded themselves to a very high standard. In other cases it had been a struggle to get anything at all on disk. Quite a few of the drum parts came in as single tracks, and not always even in stereo. Some parts were ‘mix ready’, some were vanishingly low in level, while others pushed the endstops. Some were dry, but many bore the stamp of various different domestic environments. And although the piecemeal recording process had delivered great individual performances, these didn’t always sum into a satisfying whole.

In a sense, then, this article will be less about mixing itself, and more about the preparatory work needed to make a project like this ready for mixing. I’ll be illustrating it with examples from Nick’s songs, which you can hear by going to https://sosm.ag/lockdownmixdownaudio or downloading the ZIP file below.

Editing: Undoing The Damage

Most people can spot when a note is out of time and move it a bit to the left, or use their DAW’s comping tools to assemble the best bits from multiple takes. However, inexperienced engineers often don’t make the cleanest job of tidying up after the editing process. If you solo the edited tracks, zooming right in in both horizontal and vertical axes, and listen on headphones, you’ll often notice all sorts of issues that aren’t apparent at first listen. You need to fix these even if they don’t generate audible clicks and pops, because the resulting audio will usually sound unnatural, if only on a subconscious level.

One thing that’s often neglected by home‑studio recordists is fades. Every single region boundary in a project should be protected by a fade, even if this is only a few milliseconds long — and that includes all of the new boundaries that are created by audio edits and comps.

Another common problem is gaps. Anything recorded with a mic, especially in a home studio, will have ‘room tone’ and reverberation in the background. Our ears quickly get accustomed to that when it’s consistent, but you don’t want it cutting in and out wherever an edit has been made. So check that region boundaries have been dragged out to fill gaps, and that crossfades have been used at the joins, rather than fading one region out before the next one fades in. Check also that this process hasn’t led to note attacks and drum transients being duplicated, or note tails cut off unnaturally. Something to watch out for on vocal tracks is breaths that have been truncated or doubled; it might look as if edits have been made in gaps, but these artifacts become obvious when you start to apply compression and other mix processing.

If you’ve received a DAW session to mix, any edits that need checking will be fairly obvious. But if you’ve just received a bunch of files, or if the DAW session includes tracks recorded by others, they may include edits that have been rendered. These can contain all of the problems I’ve just described, and they’re a lot harder to identify and fix. Nick’s session for ‘Tell Me What You’re Thinking’ had some audible clicks and pops on playback, even though no edits were visible. Zooming in on the double‑bass track revealed waveforms suddenly cut off, moments where the natural noise floor gave way to digital black, and so forth. Fixing these required detailed work with the Pro Tools pencil tool to draw in missing waveforms, creative copying and pasting to fill holes, and the use of the De‑click module in iZotope’s RX. I was able to get it sounding OK, though not as good as the re‑recorded version Nick did when I complained about it!

The ultimate nightmare editing scenario involves edits that span multiple tracks. Novice engineers aren’t always aware of the need to lock different tracks or regions together so that edits are applied identically to all of them. If this hasn’t been done, it can lead to strange and subtle problems where the sound of an instrument changes as the phase relationships between the different mics are altered. When you’re faced with something like this, especially if those edits have been rendered, it’s almost always necessary to ask for unedited versions so that you can do the job properly, rather than trying to unpick the mess.

Time Travel

Nick’s song ‘Wish You Well’ exemplified another common issue with lockdown recordings. “I sent the song out with the brief to make the verses bossa nova and the choruses New Orleans,” explains Nick, and his contributors had gone to town on the concept. As well as a full drum kit, the Pro Tools session included congas, guiro, go‑go bells and tambourine, plus other instruments such as banjo and piano that added their own rhythmic contributions. However, all these parts had been separately overdubbed, and the result was a piece of music that sometimes crossed the boundary from relaxed to downright messy. This was especially the case at the verse/chorus interfaces, where the musicians had to negotiate a jump from straight to swung feel. Nick had done a handful of edits to some of the parts, but I felt that more drastic measures were required before it would be possible to do a satisfying mix.

There are lots of tools and techniques available for this sort of work nowadays. Sometimes you get lucky and find that an algorithm can do the heavy lifting. Other times you need to spend a few hours dragging regions or warp points around with the mouse. But the most important things are to have a clear idea of what it is that you’re trying to achieve, and a sufficient level of detachment to judge whether you’re achieving it. The technique that worked very well on the last project you did can often turn out not to work at all on the next one, so be prepared to try out many different approaches. And when you’re evaluating timing correction, be sure to start playback a few bars before the section you’ve just worked on, so that you hear it properly in context.

Hands On Your Time

The first step is to save a copy of your session so that you can get back to where you started when things go wrong. The next step is to identify one source that you’re going to use as a timing reference. In some cases that might be the DAW’s grid. Often, it’s the drum kit. Sometimes, though, it pays to use one of the other rhythm instruments. As a rule of thumb, I’d suggest trying first the instrument that was recorded first. In this case, that was Nick’s acoustic guitar.

Once you have chosen your timing reference, it’s worth trying out any automated options you have available. For example, the multitrack version of Celemony’s Melodyne can sometimes be a real ‘get out of jail free’ card. Set the default detection mode to Universal, load in the reference part, engage Auto‑Stretch and then drag in the rest of the audio. Surprisingly often, a kind of magic will occur, rendering your multitrack free from timing slop whilst retaining all its human feel.

Unfortunately, this wasn’t one of those times, so I returned to Pro Tools and tried out two options there. For sound quality, I find Beat Detective is pretty much unbeatable, because it doesn’t use time‑stretching; it simply chops audio up into lots of separate clips and aligns them with the grid. Elastic Audio, by contrast, can introduce audible artifacts but, unlike Beat Detective, isn’t limited to rhythmic material with obvious transients. It also enables ‘concertina‑style’ warping, where you set a warp marker at either end of the section to be edited, then click and drag a third warp marker somewhere in the middle. This lets you modify the timing of a part on a large scale while retaining small‑scale feel or groove variations. (Both tools have equivalents in almost every DAW.)

Map Making

Beat Detective conforms things to the Bars & Beats grid in Pro Tools, so if you’re using an audio part as your reference, you’ll need to adapt the grid to reflect the timing of that part. This can be done manually, by positioning the edit cursor at downbeats and using the Identify Beat command, but Beat Detective also has a Generate function that will derive a tempo map from a clip. Whichever approach you take, the key point is that you don’t want the tempo map to be too detailed. If you allow Beat Detective to detect Beats or Sub‑beats within the audio and transfer those to the ruler, you’ll end up with a map that incorporates every last nuance of the part in question. The rest of your audio will sound very odd when corrected to a map like this! It’s much better to detect only Bars, and use a low sensitivity setting so that bar divisions are only detected when they’re very clear. All we’re looking for here is an outline of the general contours of the reference part.

It’s tempting to try to use Beat Detective across an entire song, but in practice, it’s better to work through it in sections, taking a few bars at a time. That goes both for the process of creating a tempo map, and that of conforming other parts to it. It’s also vital to use the Capture Selection button every time you start work on a new section, otherwise chaos will ensue with little warning! Choosing other settings is a matter of trial and error, so be prepared to hit Undo a few times before you get it right. Sometimes you’ll want to quantise every last sub‑beat, other times only whole bar or beat chunks. Sometimes you’ll want it to detect eighth or 16th notes, other times only crotchets. In really difficult cases, it can be helpful to divide the region into largish chunks of four or eight bars’ length, quantise those to the grid, and then apply a second round of correction to each. And, almost invariably, you’ll want to reduce the Conform Strength from its default 100 percent.

Once I’d got an accurate tempo map set up, the drums, double bass, congas and go‑go bells in ‘Wish You Well’ all responded well to Beat Detective. In this case it was absolutely necessary to edit the verses and choruses separately, as the former were straight and the latter had a triplet feel. It’s also vital to make sure that all the elements within a multi‑miked kit are locked together when you apply Beat Detective to them. A Strength setting of about 65 percent was sufficient to get the ‘Wish You Well’ parts into the same time zone.

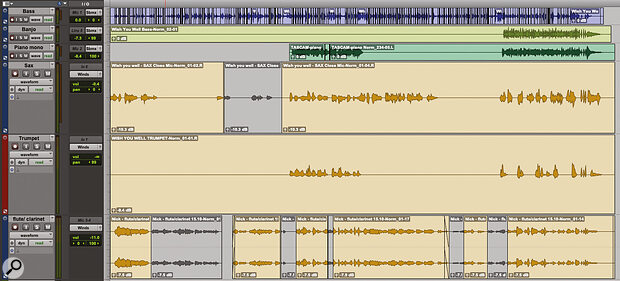

This excerpt of the Pro Tools Edit window for ‘Wish You Well’ shows the results of my timing correction. All the other parts had been overdubbed to the green guitar track in the lower half of the screen, so I began by creating a tempo map from this; the tempo changes at every bar line are visible in the ruler at the top. I used Beat Detective to nudge the timing of the go‑go bells, congas, drum kit and double-bass — the edits in these tracks result from this process. With the guiro, however, it was necessary to correct the timing manually using Elastic Audio.

This excerpt of the Pro Tools Edit window for ‘Wish You Well’ shows the results of my timing correction. All the other parts had been overdubbed to the green guitar track in the lower half of the screen, so I began by creating a tempo map from this; the tempo changes at every bar line are visible in the ruler at the top. I used Beat Detective to nudge the timing of the go‑go bells, congas, drum kit and double-bass — the edits in these tracks result from this process. With the guiro, however, it was necessary to correct the timing manually using Elastic Audio.

Beat Detective had no truck with the guiro, so I engaged Elastic Audio in Rhythmic mode, switched the track to Warp mode and went at it with the mouse. By default, Elastic Audio’s analysis only identifies potential warping points. Unless you actually click some of these to turn them into fully fledged warp markers, they won’t act as anchors, so it’s vital to do this before you start dragging them around. My strategy is to add new warp markers at the start and end of the part by Ctrl‑clicking, then step through and look for points that are already in time and don’t need editing. Since you don’t want to move these, you can add warp markers to anchor them before dragging any out‑of‑time points that fall elsewhere. The process is easier to do than to describe!

By the time I’d finished there were probably a couple of hundred warp markers in place, but it really doesn’t take that long once you get started. All in all, I probably spent a couple of hours sorting out the timing issues, and it made easily as much of a difference to the end result as the actual mixing.

In my experience, home‑studio recordings are often miked too close, perhaps in an effort to cut out unwanted room sound. This frequently leads to an excess of scratchy treble or proximity‑effect boominess.

Arriving At The Start

Once you’ve got levels under control and sorted out any timing issues, you can start to think about doing a mix. I’m not going to get into mixing technique in general in this article, but I’ll finish up with one consideration that is particularly relevant to this sort of project.

There are two senses in which a good mix needs to be balanced. Obviously, the relative levels of each part need to be set so as to produce a pleasing result. Less obviously, the timbre or tonality of the final mix needs to be balanced. When you’re working on a good studio multitrack, that tends to happen almost by default. When your session has been pieced together from lots of different home recordings, you can expect to have to do more work.

Here I’ve multed the loud and quiet sections of a drum part onto separate tracks to give me more control.

Here I’ve multed the loud and quiet sections of a drum part onto separate tracks to give me more control.  When all that the drummer supplies is a single mono file, of questionable provenance, you sometimes need to do fairly radical things with plug‑ins. In the lower screen, I’m using Oeksound’s Soothe and Spiff along with several FabFilter plug‑ins to tackle a kit recording that was simultaneously muddy and harsh. In the upper screen, I’ve multed the loud and quiet sections of a drum part onto separate tracks to give me more control.

When all that the drummer supplies is a single mono file, of questionable provenance, you sometimes need to do fairly radical things with plug‑ins. In the lower screen, I’m using Oeksound’s Soothe and Spiff along with several FabFilter plug‑ins to tackle a kit recording that was simultaneously muddy and harsh. In the upper screen, I’ve multed the loud and quiet sections of a drum part onto separate tracks to give me more control.

In my experience, home‑studio recordings are often miked too close, perhaps in an effort to cut out unwanted room sound. This frequently leads to an excess of scratchy treble or proximity‑effect boominess, and the same project will often contain some tracks that are over‑bright and others that are muddy. It can take a surprising amount of channel and/or master bus EQ to rein in these excesses and give the whole thing enough presence in the midrange. Opinions differ, but personally, I like to dial in something on the master bus fairly early in the process so that the all‑important tonality of the mix as a whole is in the ballpark from the start.

Nick’s song ‘Tell Me What You’re Thinking’ was a good example. Nick’s own acoustic guitar was flabby at the bottom end and a bit soft in the midrange, while the song also featured several solo violin and viola parts. These were beautifully played but rather less well recorded: close miking had made them scratchy and harsh at the top end, and hadn’t prevented the capture of plenty of highly coloured living‑room ambience. Luckily, we have tools today that can address these previously intractable problems. In this case, for instance, I used iZotope’s RX De‑reverb plug‑in to tone down the unwanted room tone on the strings, before coaxing the frequency balance back to something approaching normality using EQ and FabFilter’s Pro‑MB multiband. Oeksound’s unique Soothe 2 plug‑in also saw heavy use to try to tackle the scratchiness, and I bused the key parts to separate channels on McDSP’s Moo X mixer plug‑in, which is the sonic equivalent of a bath of golden syrup.

If you’ve ever hired professional decorators, you’ll know that they can paint a room incredibly fast. That’s not because they’re quicker with a roller; it’s because they know how to prepare the walls so that the paint will go on quickly. Time spent stripping the surfaces and filling in the holes is always time well spent — and so it is with mixing!

Levelling Up (Or Down)

One issue I’ve encountered a lot with home‑recorded projects is wild variation in levels. Nick Barraclough’s Pro Tools sessions were a good example. Some of his contributors had apparently normalised their parts to 0dBFS, while others had barely managed to get signal into the system at all, and Nick’s own parts were in the ‘normal’ range somewhere in the middle.

For his rough mixes, Nick had dealt with this using the faders in the Pro Tools mixer, but before you get stuck into a proper mix, level mismatches really need to be dealt with at source. Working with faders at ‑30dB is no fun, and doesn’t alter the headroom within the channel, so the signal will still be hitting plug‑ins uncomfortably hot.

The wind and brass parts on ‘Wish You Well’ came in super‑hot. Rather than work with faders halfway up their travel, and risk overloading plug‑ins, I used Clip Gain to get the levels into the right area.

The wind and brass parts on ‘Wish You Well’ came in super‑hot. Rather than work with faders halfway up their travel, and risk overloading plug‑ins, I used Clip Gain to get the levels into the right area.

My usual approach is to use the Clip Gain function in Pro Tools to adjust the levels of individual audio regions. If your DAW doesn’t have a similar function, you could use a real‑time gain plug‑in as the first insert on each track, or an offline Normalise function to render the clips at a more appropriate level. What level? Well, a good starting point is to aim for a plausible rough balance when all the faders are at 0dB, so you’re starting the mix from a level playing field. Be guided by how things sound, not by how tall the waveform looks: some sounds cut through the mix even at modest levels.