Apple continued to demonstrate a commitment to music in January at both the San Francisco Macworld and LA Winter NAMM shows, as well as releasing G5-based Xserve machines. And this month we continue exploring the G5's performance in a musical context.

I really wanted to avoid starting this month's column by saying it's been a busy month for Apple, but it's been, well, a busy month for Apple. The Macworld show in San Francisco ushered in the 20th anniversary year of Macintosh, and if Apple's musical focus last year was in the distribution of music, it looks like this year's focus will also encompass the creation of it, with the first signs of Apple's strategy for purchasing Emagic towards the end of 2002 becoming clear.

Although the rumours predicted there would be no new Macintosh hardware announced in Jobs' Macworld keynote, Apple's CEO did take the opportunity to unveil the much-anticipated G5-based Xserve upgrade, along with a revised Xserve RAID. And while these announcements were very welcome, it was curious that Jobs used a consumer show to present products that are ultimately aimed at the professional and server markets. Perhaps this was to compensate for the lack of any Power Mac or iMac revisions, especially since Jobs began his keynote by saying that it would be a great year for new products, indicating straight away that we wouldn't actually hear about any of these developments during the San Francisco keynote.

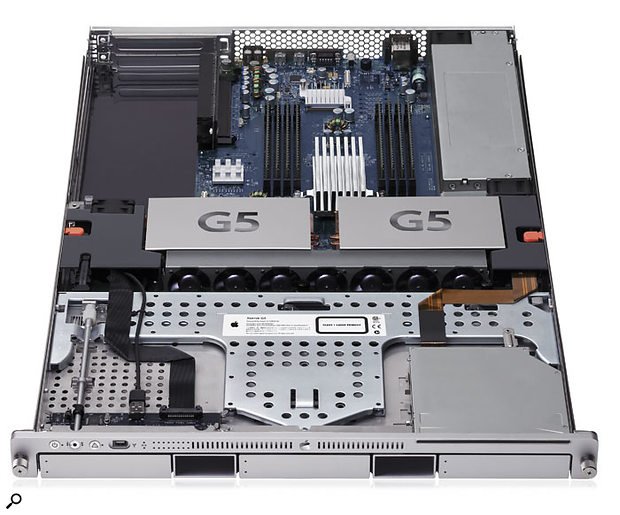

Xserve G5

The Xserve G5 is basically a server-orientated implementation of the technology used in Apple's Power Mac G5 desktop range of computers, and is available in three configurations: a single or dual 2GHz G5 server, or a dual-2GHz cluster node for those who require additional processing power without extra storage.

All models share the same basic architecture, with a 1GHz buss per processor, 512MB RAM (expandable to 8GB), two full-length PCI-X slots running at 133MHz, two Gigabit Ethernet ports, two Firewire 800 ports, a Firewire 400 port, two USB 2 ports and a 9-pin RS232 port. In terms of storage, the server models feature a slot-load Combo drive and space for three Serial ATA (SATA) Apple Drive Modules, while the cluster node features a single SATA Apple Drive Module (ADM). Both server and cluster node models come with an 80GB SATA ADM as standard.

Like its G4-based predecessor, the Xserve G5 is housed in a 1U rack-mountable enclosure, despite speculation that Apple would not be able to provide suitable cooling for the G5 in such a small space. The way the engineers seem to have solved this problem is by jettisoning one of the original complement of four drive bays in favour of two ventilation holes. It will be interesting to see just how much noise the Xserve G5 machines actually produce in everyday usage.

There was much speculation on the release of the original Xserve about its suitability as a music workstation; especially since Apple were keen to highlight the usefulness of Xserves, and, indeed, Xserve RAIDs (Redundant Array of Inexpensive Disks), in the video world. On this subject, it's perhaps a little disappointing that Apple choose to leave out the digital audio I/O from the Xserve G5, although I have to concede that including such ports would have no real purpose in the server markets Apple is targeting. And, of course, there's nothing to prevent you from using the PCI-X slots (assuming you have a compatible audio card) or the Firewire ports to connect suitable audio hardware.

Aside from aesthetics, though, the difference between an Xserve G5 and a Power Mac G5 isn't that radical for musicians and audio engineers, and most users would probably be better off sticking with the latter for the built-in audio I/O and the extra PCI slot. Far more interesting, however, is the use of an Xserve RAID for recording and playing back audio tracks, streaming samples, or both, which has been mentioned in past Apple Notes columns. The biggest improvement in the revised Xserve RAID is the larger 250MB ADMs, meaning that you can now have up to 3.5 Terabytes of storage in a single unit; although, unlike the Xserve G5, the Xserve RAID remains ATA-based rather than using SATA. Hopefully Apple will let us check this out at some point, since the potential of a G5-based computer, Logic, EXS24 and an Xserve RAID is rather intriguing.

The Xserve G5 costs either £2399, £3199 or £2399 for the single, the dual, and the dual cluster-node models respectively, while the Xserve RAID starts at £4799 for the 1TB model.

Round Two: EXS24

In last month's column we took a close look at the performance of the Power Mac G5 with the aid of Logic 's Platinumverb, but despite having more space than usual for Apple Notes, I didn't get to describe the second part of my performance tests, based on the performance of Logic 's EXS24. So now it's time to put the white coats back on again, as we answer the question that I'm sure you lose as much sleep over as I do: how many voices can the EXS24 sampler play back on a G5?

To recap from last month, the G5 in question is a dual-2GHz model with 2GB of RAM, running Logic Platinum 6.3.2 and Mac OS 10.3.1. And while I'm recapping, it's worth remembering the Emagic co-founder's comments during the keynote that introduced the G5 at Apple's WWDC last May, where he claimed the G5 could play back over 1000 stereo 24-bit voices. Was he right? And am I going to end every paragraph with a question?

In order to carry out the EXS24 test, I turned to a Harp instrument from the Vienna Symphonic Library (HA_ES, to be specific), which contains 386.7MB of 16-bit samples at 44.1kHz. I used the built-in Core Audio drivers with a buffer size of 512 samples and initially disabled the EXS24 's Virtual Memory disk streaming option so the performance of the disk and controller wouldn't impede the processor and system buss's capabilities. In Logic 's Arrange window I created a one-bar object that looped indefinitely with a 64-note cluster over the first quarter-note beat, adjusting the tempo of the song until the EXS24 's voice indicator reported that 64 stereo voices were playing back continuously.

With 11 instances of EXS24 working flat-out in the same configuration as described in the last paragraph, the first and second CPU meters in Logic showed approximately 95 and 100 percent usage respectively; the User value from OS X's Activity Monitor reported 88 percent. Adding a 12th instance overloaded the system, but even with 11 instances of EXS24, each playing back 64 voices, the total number of stereo voices was 704, which is pretty impressive.

Apple News From The NAMM Show

Walking into Hall A on the lower floor of the Anaheim Convention Centre between January the 15th and the 18th, you couldn't have avoided seeing the large illuminated fruit-inspired logo that was the back of the Apple booth at the 2004 Winter NAMM show. While the booth was really an Emagic one in all but name, this year saw the largest and most significant Apple presence at a professional music trade show, and the company took the opportunity to show off both the G5 Power Mac and G4 Powerbook hardware, along with software such as the recently-announced Garage Band, Soundtrack and, of course, Logic.

The biggest Apple news at NAMM, however, was the price and name restructuring of the Logic range to be in line with the company's Final Cut video software. Emagic's three-tiered Audio, Gold and Platinum line-up of Logic software will be replaced by two versions: Logic Pro, priced at $999, and Logic Express for $299. While Logic Pro might initially seem more expensive than Logic Platinum, Apple will now bundle every optional instrument and effect with Logic Pro at no extra charge. Yes, that means for less than $1000 you now get Logic Platinum, ES1, ES2, EVOC20, EXS24, EVD6, EVB3, and the new Space Designer convolution reverb, which, altogether, Logic users have previously paid thousands in any currency to obtain.

The biggest Apple news at NAMM, however, was the price and name restructuring of the Logic range to be in line with the company's Final Cut video software. Emagic's three-tiered Audio, Gold and Platinum line-up of Logic software will be replaced by two versions: Logic Pro, priced at $999, and Logic Express for $299. While Logic Pro might initially seem more expensive than Logic Platinum, Apple will now bundle every optional instrument and effect with Logic Pro at no extra charge. Yes, that means for less than $1000 you now get Logic Platinum, ES1, ES2, EVOC20, EXS24, EVD6, EVB3, and the new Space Designer convolution reverb, which, altogether, Logic users have previously paid thousands in any currency to obtain.

Those who have used Logic since day one probably won't feel too annoyed with the new pricing structure since they will already have benefited from Emagic's effects and instruments over the last four years, although those who have made recent purchases may be less forgiving. However, there are perhaps serious implications for the industry proceeding from Apple's actions, since the company is arguably eroding the value of software by literally giving much of it away. This bundling could possibly harm plug-in developers in the short term. How many Logic Pro users will purchase Altiverb when they already get Space Designer for free, for example?

Logic 's aggressive pricing could also have implications for other sequencer manufacturers, whom I imagine will struggle to match Apple's pricing in the professional space of the market. Can Steinberg afford to sell all their products in one box for less than the current retail price of Nuendo?

The only reason Apple can position Logic in this way is that Logic users will be locked into purchasing Macintosh hardware, which is where Apple make their profit — Apple is a hardware company, after all — so the software merely becomes a way of selling more hardware. Not that this is a bad thing if you happen to be a Logic user already, or if you happen to like Logic; but it could mean less third-party development in the future for the Mac platform, which I think would not be a good thing. A clear parallel to this can already be seen in the video world, with Adobe no longer developing Premiere for the Mac because of the market penetration of Final Cut Pro. It will be interesting to see how the music and audio markets respond to Apple's move over the coming year.

More Is Less

There's an oft-forgotten option in the EXS24 editor window's preferences that lets you select 32-bit floating-point storage for samples, rather than the 16- or 24-bit integer format of the data as it's stored on a disk. This option offers a huge improvement in terms of performance, since, as discussed last month, Logic 's audio system is based around 32-bit floating-point arithmetic. So if the EXS24 sampler stores sample data in a 16- or 24-bit integer format, it has to convert every sample into 32-bit floating-point when retrieving the data from memory. However, when the samples are loaded into memory as 32-bit floating-point, this integer to floating-point conversion isn't necessary — the only downside being that the same instrument will require either twice the memory, or a third more, when the 32-bit floating-point storage option is enabled.

Choosing 32-bit floating-point sample storage allowed me to run an incredible 51 instances of EXS24 on the G5 before overloading the system at the 52nd.In the case of the VSL 's 16-bit harp instrument, enabling 32-bit floating-point storage doubled the amount of memory required to 773.4MB — and suddenly the Power Mac G5's 8GB memory limit seemed small again! However, in terms of performance with the same 11 instances of EXS24, Logic 's CPU meters dropped to around 25 and 15 percent respectively, with the User value reporting 25 percent. Not bad. In fact, with 32-bit floating-point storage enabled I was able to get 51 instances of the EXS24 sampler playing a total of 3264 voices. At this stage in the experiment, Logic 's CPU meters read approximately 100 and 95 percent respectively, and the User value was at 90 percent. Adding a 52nd instance overloaded the system.

Choosing 32-bit floating-point sample storage allowed me to run an incredible 51 instances of EXS24 on the G5 before overloading the system at the 52nd.In the case of the VSL 's 16-bit harp instrument, enabling 32-bit floating-point storage doubled the amount of memory required to 773.4MB — and suddenly the Power Mac G5's 8GB memory limit seemed small again! However, in terms of performance with the same 11 instances of EXS24, Logic 's CPU meters dropped to around 25 and 15 percent respectively, with the User value reporting 25 percent. Not bad. In fact, with 32-bit floating-point storage enabled I was able to get 51 instances of the EXS24 sampler playing a total of 3264 voices. At this stage in the experiment, Logic 's CPU meters read approximately 100 and 95 percent respectively, and the User value was at 90 percent. Adding a 52nd instance overloaded the system.

After the 32-bit floating-point test, I switched back to 16-bit storage to see the effect of enabling Virtual Memory, so that the samples streamed from disk instead of being wholly stored in memory. However, as you can probably guess, enabling 32-bit floating-point storage makes little difference when the samples aren't stored completely in memory, since they will be read in their native storage format. Virtual Memory was configured with Disk Speed set to Medium and Disk Activity set to Average, requiring a constant RAM allocation of 15.1MB. With this setup, nine instances of EXS24, playing 576 voices, pushed both of Logic 's CPU meters to the limit, with a User value of 92 percent, and the system performed better with eight instances playing 512 voices.

Another factor that makes a big difference to the performance of the EXS24 sampler is whether the filter is enabled or not. With 32-bit floating-point storage and Virtual Memory disabled I managed only three instances of the EXS24 sampler (192 voices), each with the filter enabled. In this context, Logic 's CPU meters showed approximately 60 and 100 percent usage respectively, with the User value indicating 75 percent. Adding a fourth EXS24 instance with the filter overloaded the system. Enabling 32-bit storage allowed the fourth instance to be added, while adding a fifth overloaded the system. With four instances playing 256 voices, Logic 's CPU meters each gave a reading of around 85 percent, with the User value showing 73 percent.

Caveat

While the figures described above are certainly pretty impressive, I have to admit that there's a slight flaw in my test, given that every sampler is playing back from exactly the same part of the memory; and given that the same notes are being repeated, there's a good chance that the system's caches are giving a slightly skewed performance result. A better test would be to have random notes being played with a different instrument loaded on every EXS24 instance, although I haven't had time yet to delve this deep. Even so, the tests described here are at least useful to show what the absolute maximum performance of the G5 would be, depending on how you're using the EXS24 with regards to sample storage, Virtual Memory and filter settings.

And finally, just in case you were wondering: since this month's column needed to be finished before the actual release of the Garage Band sequencer with the iLife '04 suite of programs, we'll be taking a closer look at Apple's foray into the entry-level sequencing market in next month's Apple Notes — stay tuned.