Colin Cartmell’s decades‑long tonequest has led him to create some of the best guitar cabinet IRs out there — so we asked him for advice on how to roll your own.

Most guitarists will be very familiar with the idea of using impulse responses (IRs) to impose the character of ‘sampled’ speaker cabinets on a guitar signal. They’ve long been useful in a studio setting, but when guitarists in bands at every level are touring and performing with modelling software running on laptops, or high‑end hardware modellers such as the Line 6 Helix, the Axe FX and the Kemper Profiler to drive in‑ear monitors and/or powered full‑range, flat‑response (FRFR) guitar cabs, you know that cab IRs have moved beyond the studio to the stage.

Some of the best IRs I’ve heard are those from JTC Tones, whose Cyber Driver and Daemon Driver collections I reviewed back in SOS October 2021 (https://sosm.ag/jtc-cyber-daemon). But it wasn’t only the libraries themselves that impressed me: in researching that review I spent quite some time talking with Colin Cartmell, the guitarist and music technologist who created, developed and curated those collections, and I was struck by the extraordinary lengths he’d gone to in order to create them. A few weeks ago, I got back in touch to see if I could tease out some useful advice for SOS readers on how to go about making their own IRs and how to get the best results with them. We enjoyed a wide‑ranging discussion about what Colin feels really contributes to ‘guitar tone’ and what aspects of it can and can’t be delivered using an IR. We explored the capture process, the post‑capture manipulation of the result, and how to use a captured IR to its best advantage. And since Colin’s decades‑long journey of tonal exploration provides important context, I’ll take you through some highlights of that in a separate box.

Colin’s JTC Tones cabinet IR collections were developed with a slightly different ethos from most libraries.

Colin’s JTC Tones cabinet IR collections were developed with a slightly different ethos from most libraries.

What Is Guitar Tone?

To really understand how an IR is contributing to your sound, you have to understand what goes into ‘guitar tone’ more generally, and Colin is keen to stress that every tone is the result of a unique combination of all the elements in the chain: everything that can affect the harmonic profile of the signal, from the string beginning to move within the magnetic field of a pickup pole piece to the amplifier’s power stage driving a speaker cone to produce the sound waves in the room. Colin views each stage, including the amp’s volume level, as being like an EQ filter, since a change in any part of the chain will, to a greater or lesser extent, affect the frequency profile of the overall tone.

Consistency, then, is vital when you’re trying to develop a guitar tone: he advises that it’s best to change only one element at a time, and decide whether or not you can hear a difference before changing anything else. Interestingly, Colin suggests that in developing your tone, you start at the very beginning of the chain — despite the undoubted importance of the guitar’s design (the wood that it is made of, its pickups, string gauge and so on), he considers the plectrum material to be one of the most important elements in a guitar tone. This, he says, can have a large effect on the harmonic content in the vibrating string, and that obviously impacts on everything else in the chain, so he regards experimenting with different plectrum materials and thicknesses as an essential precursor to developing your personal tone. He tells me his change from celluloid pick to Jim Dunlop’s Ultex was responsible for a significant and beneficial change in his own sound.

After the pick, strings and guitar, comes the amp, of course, which for those using IRs could mean a real amp and a load box of some sort (the best of which can produce superb results), or a hardware or software amp modeller. Some of us will already have developed a sound with amps used in rehearsal rooms and on stage, and be looking to replicate that setup. Others, whether through choice or not, will be developing their new guitar tones at home. Colin reckons that a potential risk with modeller‑based amp sounds is that the player fails to put in the same time and effort (and, perhaps financial investment) that they would if building and editing a tonal chain in the physical world. If you don’t work hard enough, he says, everyone ends up sounding much like everyone else, no matter what software or hardware is used!

Colin views cabinet IRs as the last ‘EQ’ in the chain, and believes they have the capability to make or break a guitar tone. The vast majority of cab IRs are of loudspeakers made by well‑known manufacturers in conventional cabinets, and recorded using a pretty standard selection of mics, with each IR marketed on the accuracy of its reproduction of the sound of “that loudspeaker from that manufacturer in that type of cabinet recorded through that type of microphone at that distance etc”. This, again, can lead to players using similar sounds. In developing his JTC IRs, Colin does cover such setups, but describes his Cyber Drivers library, as “loudspeaker cabinets that have never existed until now,” and designed it for those interested in crafting a more individual tone.

Setting Up for Capture

For Colin, the process of capturing an IR begins with a decision between creating a “clone” of a particular loudspeaker cab or making what he refers to as a “custom” creation. Then, he says, “the process begins with getting the loudspeaker sounding good in the room. I start out by selecting a guitar and pickup combination that will suit the sound of the IR that I am aiming to create.” Yet, he also stresses that it’s all about capturing the speaker/cabinet/mic combination, without the ‘filters’ in the rest of the chain. “I do not use the preamplifier tone controls,”“ he told me, and suggests that “the room itself is not important, as I don’t capture any room sound in the IR.”

Colin Cartmell: "I have spent weeks on some IRs trying to find the volume level that works for the loudspeaker whose sound I want to capture."

More important is how hard the speaker is driven. “I begin by playing a guitar in a controlled, basic way at a relatively low volume level through a solid‑state preamplifier and power amplifier combination which is set flat.” Then, he will “tweak the volume up or down until the loudspeaker sounds good. What I’m listening for from the loudspeaker is the character and harmonic response that I want to hear. I have found that a very minor change in volume level can result in a large change in the sound of the loudspeaker.” Colin also hinted at the great lengths he goes to to perfect his IRs: “This is very much a trial‑and‑error process, and I have spent weeks on some IRs trying to find the volume that works for the loudspeaker whose sound I want to capture.” If the volume is too low, his experience is that the cabinet resonances will dominate and change the EQ profile of the capture, whereas if the volume is too high the capture will sound, in his words, “woofy”.

“Once I’m happy with the sound of the loudspeaker,” he continues, “I move on to determining the best‑sounding point on the cone for the microphone that I decided to use for the capture.” Finding this ‘sweet spot’ can again be time‑consuming, with mic movements sometimes as small as a millimetre at a time. Colin will record as he goes until he finds the spot at which the sound coming out of the monitors reflects what he heard whilst playing in the room. He also stressed that the process is not precisely repeatable, since a cab IR inherently captures the cumulative ‘EQ filter’ effect of the entire chain; changing the settings on or replacing any item in that chain, including the volume, will tend to move the miking sweet spot!

Capture, Edits & Processing

With the overall tonal chain from guitar to microphone established, Colin returns to his basic goal when capturing IRs of the setup to, as far as possible, take all the ‘filters’ other than the speaker, cabinet and mic out of the equation. To that end, he removes the guitar, any pedals and the amp, and replaces them with a flat‑response solid‑state amplifier, which drives the speaker cabinet with a full‑frequency sine‑wave sweep of 20 or 60 seconds. Finally, he records the result and runs it through a deconvolution program (eg Logic’s Impulse Response Utility) to produce an impulse response.

Normally, he says, the raw impulse response will then require editing to remove silences at the beginning and end, and to adjust the fade‑out time in order to trim it to the required length. Colin recommends an impulse length of 20 to 41 ms, since going longer will start to capture the room effects and, of course, it will add more latency.

Trimmed IR waveforms before and after Colin’s primary EQ treatment.Inevitably, Colin isn’t keen to divulge the full details of his proprietary MHVT process (see 'Colin's Tonequest' box), but he does suggest experimenting with EQ. His major tip is to use only subtractive EQ moves, as the most useful application is “to use take out harmonics and spikes in the IR’s frequency response curve that I don’t want to hear, using very tight parametric EQs”, and, more generally, he feels that boosting frequencies tends to lend an “unnatural” sound, undoing all the hard work put into setting up the tone to capture!

Trimmed IR waveforms before and after Colin’s primary EQ treatment.Inevitably, Colin isn’t keen to divulge the full details of his proprietary MHVT process (see 'Colin's Tonequest' box), but he does suggest experimenting with EQ. His major tip is to use only subtractive EQ moves, as the most useful application is “to use take out harmonics and spikes in the IR’s frequency response curve that I don’t want to hear, using very tight parametric EQs”, and, more generally, he feels that boosting frequencies tends to lend an “unnatural” sound, undoing all the hard work put into setting up the tone to capture!

A 20‑41 ms WAV file is short, of course, so for editing he’ll generally load it into a DAW, and zoom in until he can see its waveform clearly. If you don’t feel comfortable editing an IR directly, he suggests using an IR loader such as Redwirez mixIR3, which allows you to EQ and mix single or multiple IRs.

What Colin doesn’t recommend is applying EQ to the captured sweep before it’s been deconvolved. He feels that, for whatever reason, this again adds an ‘unnatural’ edge. A better tactic, he suggests, is either to change the mic, or set up a second mic in its own sweet spot and capturing it alongside your original mic, then deconvolving them separately. You can use the IRs separately or mixed together, as you prefer — whichever works best for you.

Some amps are noisier than others, so does he use noise‑reduction? “I don’t use any ‘hiss reduction’ techniques other than ensuring that the sweep is well above the amplifier noise floor. My experience is that capturing an IR with excessive hiss leads to a poor‑sounding IR, and trying to correct a ‘hissy’ IR just leads to more problems.”

Using Cabinet IRs

Arguably the most important piece of advice Colin offered about using your IRs is that you shouldn’t build up unrealistic expectations about what can be achieved using IRs. They don’t react dynamically to the signal level, so, while a Marshall JTM45 running into a loadbox with the finest 4x12 cabinet IR in the universe will give you a great result, it can never feel or sound precisely the same as the real thing.

What you can do, though, is compensate for this to some extent, and a great technique Colin shared — I’m definitely going to use this going forward — is to run the output from an IR into your favourite tape saturation plug‑in. This can add in just enough of a sense of the nonlinear loudspeaker distortion that a single IR just isn’t capable of capturing. Colin discovered this technique after trying, and failing, to achieve that effect from both real and emulated distortion pedals. He’s also a big fan of mixing cab IRs together, but he recommends using only two IRs at any one time and, for best results, to use IRs that sound very different from each other.

It’s A Wrap

I really enjoyed talking with Colin. He has a strong, very personal tonal vision, and has developed a unique way of creating cabinet impulse responses that goes far beyond the approaches used by the vast majority of developers. If you haven’t already tried his commercial IRs, you can get a free download of two of his Daemon Drivers from the JTC Tones website at www.jtcguitar.com/jtctones.

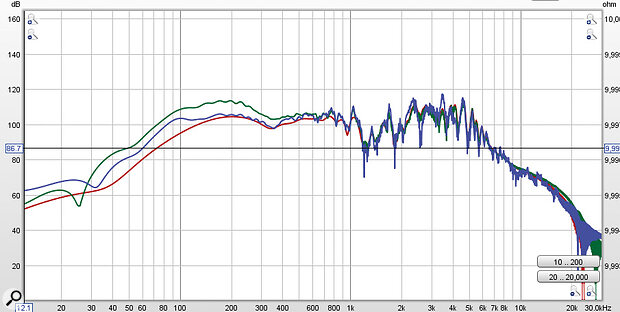

The frequency responses of three Redmere Soloist combo IRs, which Colin created specifically for SOS readers. The ‘raw’ untreated IR is in red. The initial EQ‑optimised version is in green. And, in blue, the Track version has been optimised to be more generally ‘mix ready’, with more subtractive EQ.

The frequency responses of three Redmere Soloist combo IRs, which Colin created specifically for SOS readers. The ‘raw’ untreated IR is in red. The initial EQ‑optimised version is in green. And, in blue, the Track version has been optimised to be more generally ‘mix ready’, with more subtractive EQ.

Exclusively for SOS readers, though, Colin has also created three unique cabinet IRs which demonstrate his process, and you can download them for free from the SOS website, at https//:sosm.ag/capturing-cabinet-irs.

![]() colin-cartmell-downloadable-irs.zip

colin-cartmell-downloadable-irs.zip

The first IR is a raw, unprocessed capture of his Redmere Soloist’s preamp, ‘Fender Twin’ channel, power amp and left‑hand loudspeaker via a Shure SM57 microphone. The second one is a more ‘polished’ version of the original, in which Colin has removed the effect of the EQ filtering introduced by the Soloist’s preamp, emulation and power amplifier, leaving just the sound of the Soloist’s G12‑80 loudspeaker and the Shure SM57 mic used for the capture. For the third, he’s refined the same IR using a bit of EQ, as he typically would for use in a track. Now it’s over to you to see what you can do with them!

Colin’s Tonequest

Colin Cartmell’s fascination with guitar sounds began in the 1980s, when he heard the D5 power chord that kicks off Aerosmith’s ‘Young Lust’, the first track on their 1989 album Pump. His sister had to tell him that he was listening to an electric guitar, and his desire to emulate that sound led to the purchase of a Kay guitar, a 5W tube amp and, pretty soon after, a fuzz box.

Pump’s producer, the late Bruce Fairbairn, was famed for his work with guitar‑based bands such as Bon Jovi, AC/DC and Van Halen, and in the 1980s Colin found himself attracted to the highly processed guitar tones that characterised these productions, amongst others. This, in turn, led him (and many other guitarists, myself included) to discover the Tom Scholtz Rockman, an all‑analogue headphone guitar amplifier, and Colin now owns almost all its variants! Developed by Tom Scholtz (of the band Boston, but also a trained electronics engineer), this was engineered to simulate a full‑volume amplified guitar, and featured compression, distortion, stereo chorus and echo.

Driven by his desire to access that 1980s processed tone in his own playing, Colin took up Joe Satriani’s ‘Boss DS‑1 into a clean Marshall’ approach, using a selection of overdrive and distortion pedals into clean amps, which got him into the 1980s MOSFET Marshalls. Whilst studying for a BTEC in Music Production in 1999, he bought an original Line 6 POD, right at the beginning of the amplifier/loudspeaker modelling era. But he didn’t like the excessive ‘honk’ he heard in its cabinet emulations, preferring instead his fully analogue 1991 Zoom Player 2020 multi‑effects for drive and EQ. It’s a unit that he still uses to this day and although Colin contends, tongue in cheek, that the Rockman‑like livery of the 2020 may have something to do with its continuing presence on his pedal board, the unit’s JRC4558 chip (also found in the original Ibanez TS‑808 Tube Screamer) delivers the drive sound that keeps it there.

Colin’s Redmere Soloist combo — a rare, all‑analogue device that has the honour of being the World’s first modelling amp to enter production — has had a significant influence on his approach.Continuing down the modelling route, Colin invested in the Yamaha DG‑series preamp, cabinets, combos and heads that appeared just after the POD. He owns examples of almost the entire range, although the DG Stomp didn’t make the cut. Colin describes this range as being the most tube‑like of the modelling amps of that era, likening their performance to that of a “POD without the honk”. One aspect of the DG series that Colin thought highly of at the time was that Yamaha made no attempt to market the units on the back of the modelled originals — as a user, he had to approach it with an open mind and use the models to develop his own sound, rather than be straight‑jacketed by tonal preconceptions. (Yamaha finally released the list of the DG series’ modelled amps in 2012).

Colin’s Redmere Soloist combo — a rare, all‑analogue device that has the honour of being the World’s first modelling amp to enter production — has had a significant influence on his approach.Continuing down the modelling route, Colin invested in the Yamaha DG‑series preamp, cabinets, combos and heads that appeared just after the POD. He owns examples of almost the entire range, although the DG Stomp didn’t make the cut. Colin describes this range as being the most tube‑like of the modelling amps of that era, likening their performance to that of a “POD without the honk”. One aspect of the DG series that Colin thought highly of at the time was that Yamaha made no attempt to market the units on the back of the modelled originals — as a user, he had to approach it with an open mind and use the models to develop his own sound, rather than be straight‑jacketed by tonal preconceptions. (Yamaha finally released the list of the DG series’ modelled amps in 2012).

Perhaps the greatest influence on Colin’s quest for the ultimate tone was his purchase, circa 2005, of a very rare amp: a mint‑condition Redmere Soloist. Manufactured between 1978 and 1979 by Cambridge‑based PA:CE, the all‑analogue Soloist has the honour of being the very first modelling amp to enter production. Colin describes the Soloist as an amp that he “liked but didn’t know why”. Although there was never any official confirmation of the amp models it was based on, PA:CE’s promotional material hinted at a Fender, Marshall and Vox line‑up.

Much as he liked the Rockman, the Zoom 2020, the DG Series, the Redmere and various other amp sims he encountered, Colin was never quite satisfied with their cabinet simulations — and that’s why he decided “to create a virtual cabinet which would work together with the guitar to augment the guitar tone and highlight its character in an organic way”.

Before moving into IR creation, Colin experimented with modelling hardware using switchable analogue components: he still uses this Tone Zone box today.At the time, he knew nothing about IR technology, so his first thought was to build a hardware unit, and on checking the internals of his Redmere Soloist he noticed the sheer number of capacitors and resistors on the circuit boards responsible for its emulations. It was this which prompted him to design his one‑of‑a‑kind Tone Zone pedal. The Tone Zone contains several complex filter modules, each mounted on its own circuit board. Developed and tuned by “trial, error and ear” using components selected from a large stock of vintage capacitors and resistors donated by his uncle, these filters are selected individually using a rotary switch. A Blend knob controls the mix between filtered and unfiltered signals and an In/Bypass mini toggle switch takes the selected filter in or out of circuit.

Before moving into IR creation, Colin experimented with modelling hardware using switchable analogue components: he still uses this Tone Zone box today.At the time, he knew nothing about IR technology, so his first thought was to build a hardware unit, and on checking the internals of his Redmere Soloist he noticed the sheer number of capacitors and resistors on the circuit boards responsible for its emulations. It was this which prompted him to design his one‑of‑a‑kind Tone Zone pedal. The Tone Zone contains several complex filter modules, each mounted on its own circuit board. Developed and tuned by “trial, error and ear” using components selected from a large stock of vintage capacitors and resistors donated by his uncle, these filters are selected individually using a rotary switch. A Blend knob controls the mix between filtered and unfiltered signals and an In/Bypass mini toggle switch takes the selected filter in or out of circuit.

Designed to be positioned at the end of a pedal chain, the Tone Zone remains an important part of Colin’s tonal approach to this day, as it gives him extensive and precise control of the tonal profile of the guitar signal going into an amp. But the increasing availability of software and hardware for creating and using IRs, as well as the developments in the quality of amp modelling technology, offered him more potential to realise his ambition of creating the virtual cabinet of his dreams. So he began the development work that led eventually to his own proprietary Modern Vintage Hybrid Technology (MVHT) approach, and to the Daemon Driver and Cyber Driver IR series.