David Mellor looks at the roles of computers in the modern studio. This is the second article in a four‑part series.

Until very recently, it was taken for granted that the centrepiece of any recording studio, large or small, would be the mixing console. Now it is often the computer. The computer can play the major roles of MIDI sequencer, multitrack audio recorder, stereo recorder and, in addition, the supporting roles of sample and synth editing. It can even be a sampler or synth. Mixing and effects are rapidly becoming a practical proposition, and it may be that the next time you think about changing your mixing console it will be simply to get rid of it and not replace it, because the computer can do all the mixing you need. Perhaps one day the computer will be the studio, aside from the mics, monitoring and acoustics — not for all of us, perhaps, but quite possibly the majority. Let's look at the functions of the computer in turn and see what it might do for your studio, starting with MIDI sequencing.

MIDI Sequencing

This, and word processing, is what computers were made for. You can't word‑process better than on a computer, and if you can't create the MIDI sequence of your dreams on a computer, then no stand‑alone hardware sequencer will do a better job. MIDI, as you know, starts as key‑presses on a piano‑style keyboard, or other controller, and becomes data — such as note number, key velocity, aftertouch, and so on. The job of the MIDI sequencing software is simply to record that data and allow you to manipulate it in various ways. It doesn't sound too complicated, and in fact it is quite an easy task for the computer to perform, but the fact that the perfect sequencer has yet to be invented shows that the technical performance of the sequencer doesn't matter as much as the way the software interacts with the human operator — the musician.

Different sequencers have different 'feels', as different as the necks of different guitars.

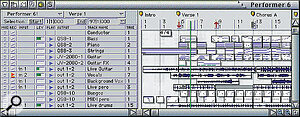

Most people use sequencers to build up a composition instrument by instrument — synthesized or sampled, of course. I personally might start off with a guide track for a song using a piano and strings program on my keyboard. Then I will record drums, bass and all the other elements of the arrangement, eventually replacing the guide track. In the process of doing this, I will probably at some stage decide that there ought to be a few extra bars here, a few bars cut out there, and that there might be certain inadequacies in my performance that need fixing, such as wrong notes or poor timing. Any decent sequencer software can handle all of this, so how do the various products on the market differ and how do you decide which to buy? Firstly, take a look at the display. Does it look simple and sensible to you, or does it seem complex and over‑fussy? You will be interacting with the display for much of your recording day and you really do need to feel comfortable. For example, look at Figure 1 (above), which shows the transport bars of two sequencers. Which do you prefer? To me, one seems well laid out and logical, the other cryptic and not at all intuitive, but I know people who think the opposite, so it really is a personal decision.

Most sequencers use an overview display (see Figure 2 below) of segments which represent snatches of MIDI data — or phrases of music, if you like. You can grab segments with the mouse and move them or copy them elsewhere in the composition, or to other tracks, to be played by other instruments. This is something else you'll be doing a lot, so you should try and get a comparative demo. Different sequencers have different 'feels', as different as the necks of different guitars. There was a version of one major sequencer, not now current, where I found it difficult to grab the segments, and frequently I would 'drop' a segment before I had managed to move it. On another, still current, I keep forgetting that I have to press a certain key before I grab the segment I want to copy when really I feel I should be able to press the key before or after, as I can in other software. You might think that these are small points when the software designers keep bombarding us with the magnificence of their feature sets, but I think the way the software responds to the operator is vitally important and deserves more attention than it usually gets.

During the sequencing process, one facility that is used (over‑used?) more than any other is quantisation, which you may regard as the simple matter of aligning notes to their correct positions in time. Different sequencers have different options, however. All sequencers offer basic quantisation; some go further and allow quantisation of the beginnings and/or the ends of the notes. Some make it easy to set a given duration for each note. Most have a swing function where offbeats can be delayed by a certain amount. Beyond that there is a wealth of quantisation effects, usually known as 'grooves', where your playing can be quantised in various creative ways — sometimes to the style of another musician. These features are worth investigating when choosing a sequencer, but also check that any groove quantising feature, if available, makes sense to you. If it's too complex, you simply won't use it. A further quantisation feature often provided is the ability to match the positions of notes in a segment to those in another segment, even if the previous segment hadn't been quantised. I use this technique by playing, for instance, 20 or so bars of hi‑hat, selecting the best bar and looping it, and then forcing other rhythmic parts to the same quantisation. It can be very effective, and a means of 'humanising' the sequence.

For note editing, sequencers offer various means of editing in bulk, or editing individual notes. For example, you might want everything to be a little bit louder, quieter, longer, shorter, earlier, later, etc. All decent sequencers offer such editing facilities but, once again, it's a matter of usability, and of how the software fits in with the way you think about music. Editing individual notes tends to be pretty much the same from one sequencer to another — fiddly — but it's often worthwhile to fix one bad note in an otherwise well played section, rather than trying to play it all again.

I have mentioned just a few of what I consider to be the important aspects of sequencer software. Once you've trawled through manufacturers' literature, web pages, SOS reviews and, most importantly, have had a thorough demonstration at your pace of understanding, you will have chosen a sequencer and will be ready to choose a computer and other hardware. Note that this is usually considered to be the correct way of doing things — choose the software first and then the hardware on which to run it. Some sequencers are Macintosh only, some are PC only, some are available for both platforms. Where MIDI data only is involved, a sequencer doesn't really stretch a modern computer and most current models will be fine. It's always best to follow the software designer's recommendations, however, and preferably buy a computer at least a little bit faster and more powerful to allow for the inevitable software updates/upgrades in the future.

You'll also need to buy a MIDI interface. There's a wide range available, for both Macintosh and PC, and these were detailed in Sound On Sound in July and August 1997. They range from simple but effective models, with one MIDI In and Out, up to all‑singing, all‑dancing units offering up to 240 MIDI channels. Some include synchronisation to SMPTE/EBU timecode, so that you can link your sequencer to a multitrack recorder, digital or analogue.

Audio Sequencers

A so‑called audio (or MIDI + Audio) sequencer is a MIDI sequencer with additional audio recording facilities which will soon make the MIDI‑only sequencer seem old fashioned. The idea is that you can combine guitar or vocal tracks easily with MIDI sequenced tracks, and move and copy segments in a very similar way. Audio sequencers rely heavily on the performance of hardware installed within or connected to the computer. I said earlier that you should select the software first and then buy appropriate hardware, but in the case of audio sequencers, you'll have to consider the capabilities of the software and audio recording hardware together, and then buy a computer that will suit both. Let's look at the hardware side first.

Macintosh computers have stereo audio recording hardware built in, which can be said to be of CD quality since it has the same 16‑bit resolution and 44.1kHz sampling rate (in most current models). The audible results don't bear these figures out, however, and the output is a little on the noisy side, although still usable. According to the speed of the computer, it is possible to mix anywhere from eight to 32 tracks (you will need a fast hard disk array for the latter figure) into the stereo output. PCs don't have audio built in, but can be fitted with a soundcard. Some of these cards have synthesis and/or sampling facilities but do not allow hard disk recording. Although these types of card have potential, my personal feeling is that at the moment it is generally a better option to buy separate MIDI sound modules and samplers, although I expect to be persuaded otherwise over the course of the next year or so. At the low end of the market for PC hard disk recording cards, there are some with a similar performance to the built‑in audio of the Macintosh but, Mac or PC, I really think we should be looking at something a little more professional in capability.

There are now a number of manufacturers involved in professional music and audio who offer soundcards and modules of the standard we should be looking for, which is a sound quality approaching that of an ADAT or DTRS digital multitrack recorder. Some approach this standard more closely than others, so a look at the specifications is called for — signal‑to‑noise ratio is key, and a figure of 92dB or more is the target. Aside from the audio quality, one important factor will be the number of inputs and outputs. With two inputs and outputs, obviously stereo recording is possible. It should also be possible to replay more than two tracks through the stereo outputs, although mixing and the addition of effects will have to take place within the computer. Cards with up to 12 separate outputs are now available, and multiple cards may be used, which means that the computer can be used almost as a conventional multitrack recorder and the outputs mixed through a console in the normal way. This is a very effective way of working. On the input side, it's fine for a card with multiple outputs to have only two inputs, because for many types of recording two inputs are all that you need at any one time. If you want to record a band all playing together, however, you will need more inputs. Once again, up to 12 inputs are available on a single card. If you look further up the price scale to systems which handle the audio in an external module in addition to a card, then even more inputs and outputs are practical — but it costs.

There are problems, however. Firstly, hard disks have a limitation on how many tracks they can record or replay at the same time. A fast, so‑called 'AV' type, disk can manage up to 16 these days, although a standard disk may not be able to achieve more than eight reliably. Secondly, although manufacturers of soundcards may say that multiple cards may be used, having more than one may place a severe strain on your computer's capabilities. It isn't just the processor speed, although that is important. The buss speed is important too, and buss speed is usually tucked away somewhere deep in a computer's specifications. A figure of 50MHz would be reasonable today, but 80‑100MHz should become feasible over the course of the next year.

When you've found an audio recording card that suits your purposes, you need to find a sequencer that will support it, since, unfortunately, not all sequencers support all cards. As with MIDI‑only sequencers, there are differences in operation which will, on demonstration, sway your preference. Audio sequencers now come with a selection of effects, such as equalisation, delay, chorus and reverb. The operation and quality of the effects will almost certainly be important to you. There are also differences in support for third‑party effects in the form of software 'plug‑ins' (see box, left). A thorough read of the software manufacturer's literature is called for.

Hard Disk Recording

Figure 2: MOTU's Digital Performer overview screen.

Figure 2: MOTU's Digital Performer overview screen.

There is a thin and blurred dividing line between audio sequencers and hard disk recording systems. It's easier for me to look at the top end of the market, where there is a small but growing number of systems which use a combination of cards and external hardware to process the audio, with the computer acting, for the most part, as a dumb controller. This is potentially the ideal situation, because audio, even in digital form, really needs its own environment and should not have to jostle for position with other types of digital information on the computer's data buss. Also, the computer is relieved of the strain of dealing with multiple streams of audio, and so does not necessarily need to be the latest, fastest or best model. Systems such as this major in audio, and MIDI — if available — is an extra; you may need to synchronise the hard disk recording software to a sequencer, which is often possible. In terms of audio, these systems are coming to the point where anything you might want, sonically, can happen within the system — an external mixing console and effects rack are almost becoming irrelevant. With some systems, it's also possible for the hardware to be controlled by an audio sequencer, so you get the best of both worlds. As with audio sequencers, you need to check numbers of inputs and outputs, the number of tracks possible, and the mixing and effects features.

Hard disk recording and mixing, however well specified the system, are not really suited to control via a keyboard and mouse interface, and the current wave of products coming onto the market may also offer a physical knob‑and‑button interface as a controller. Ideally, controllers such as these should have motorised faders and knobs which have a ring of LEDs or similar indicator to show their position. Otherwise, you will frequently find that the fader or knob is in a different position to where the computer thinks it should be, which is an irritation.

Considering the incredible advances in technology over the last year or so, before long we might find that the computer itself almost disappears and becomes the powerhouse behind a controller and display interface which are totally directed to our needs as musicians and recordists. When this happens, the traditional recording studio may finally disappear.

Next month — the 'traditional' recording studio (it hasn't gone away yet!). I'll return to computers later in the series, when I discuss mastering in detail.

It Has To Be Asked...

Why do you want to have a computer in your studio?

Four simple potential answers...

- I love computers!

- I want to record dance music.

- I want to create music that is new and wonderful.

- I want to sound like a band, and the computer can substitute for the other musicians.

There are many reasons why anyone might want to have a computer in their studio, but I guess these are the four primary motivators. If you don't have a computer in your studio, or you're thinking about an upgrade, don't rush out and buy one just yet, because you need to make a very carefully considered decision on whether you actually need a computer, and which type and model you should buy. Strangely enough, it's still possible to make music without a computer, so you may decide that the computerised studio is not for you. But computers have found their way into virtually every field of human activity, and they have the potential to allow you to make better use of our own abilities, and hopefully make better music, whatever your style.

- LOVING THE COMPUTER

The anorak‑wearing computer nerd is a popular fantasy figure. Undoubtedly they do exist, and I think it's true to say that there is a little bit of the nerd — sorry, technology enthusiast — in all of us. Let's face it, if there wasn't we would be reading Violin Monthly instead of Sound On Sound! Not that I have anything against violins, of course. We want our music to sound modern, and to create modern music we need hi‑tech equipment. This accounts for our interest in technology, which sometimes grows a little out of proportion into an interest in the technology for its own sake. I don't see any particular harm in this, but it's important to recognise that the urge to own and operate the equipment is a different thing to the urge to create music. It's possible to confuse the two and end up spending more time and energy on setting up a studio than on actually using it. Some people even end up writing magazine articles about setting up studios...

- DANCE MUSIC

However great your love of computers is, it can't be any greater than the love some people have for dance music. The sole intent and purpose of dance music — one might imagine — is to allow people to go out and have a good time. But I have met those who listen to dance music with an intensity that would put some classical music fans to shame. And the creation of dance music is as artistically challenging as any other style of music — perhaps more so, since it evolves so rapidly. In fact, you don't need a computer to produce dance music; a lot of dance music has been created using the Akai MPC60 sampling drum machine/sequencer, and the more recent MPC3000. Obviously, such equipment uses computer architecture internally, but there is no mouse, no monitor and no typewriter keyboard, and it's presented as a tool to fulfil a specific task. The latest MPC2000 may be similarly successful. But for most dance music producers, the computer will be seen as an essential element in the studio, alongside the twin decks and sampler.

- THE NEW AND THE WONDERFUL

New technology often leads to new musical styles. Let me tell you that there's something big on the way right now. I don't know what it is, or whether it will happen this year or next, but there is so much new technology in the form of software 'plug‑ins' available that there could be a change in music that could amount to a revolution. As I have said elsewhere in this article, plug‑ins are small software elements that can be linked to major sequencing and hard disk recording applications. They are relatively easy for software designers to create and market and they range from standard audio processes to weird, wacky and totally way‑out. It's like the primordial soup all over again, where molecules randomly organised themselves into amino acids, then into proteins, then into life — and it's going to happen to music. You could be experimenting with a couple of plug‑ins on an otherwise idle afternoon, when suddenly you realise that you have created a sound that has never existed before. It may be crap, but perhaps someone else is simultaneously discovering a combination of sounds that will form the basis of a totally new music!

- THERE IS NO SUBSTITUTE!

Computers may be versatile, but the one thing they can't easily do is emulate real live musicians. In my other life as a small‑time music publisher, I receive demo tapes at the rate of one or two a month produced by people with a musical talent, a computer and a soundcard, who aspire to write film or TV music. Often the music has the potential to sound great if played by a band or orchestra, but the computer is, by nature, a machine, and the recording almost inevitably sounds mechanical rather than human. Having said that, if you really work at it, it's possible to inject humanity into a computer‑produced recording, but I should advise that it is going to be very difficult and you would find it easier, if rather more expensive, to hire session musicians, who will give your music the human touch, amazingly enough, without any special instructions to do so! If you can't afford session musicians and you're going to try to create the sound of a band or orchestra with the aid of a computer, my first piece of advice would be to moderate your use of the quantise function; my second would be to consider at every stage whether your work sounds human or mechanical. Beyond that it's up to you — it can be done, but you're setting yourself a hard task.

Long‑Term Storage

One particular problem with recording audio onto a hard disk is long‑term storage. When a fixed hard disk is full, you have to erase something to record another piece of music. It is possible to back up onto DAT, but this is time‑consuming and there is no verification of the data during backup or restore. A better option is removable storage. The Iomega Jaz drive can be bought for around £250‑£300, with 1Gb disk cartridges (equivalent to 100 minutes of stereo audio) available for around £80.

If I Had To Start Over

If my studio burnt to the ground and I had to re‑equip from scratch, what equipment would I personally choose? This isn't a comprehensive listing, just a selection from what I consider to be the most significant products around.

Assuming that I wanted to make the computer the centrepiece of my studio rather than the accessory that it is at the moment, I think I would want a system that would fulfil almost all my needs without resorting to extra racks of equipment. This, believe it or not, is now possible — with the obvious exceptions of mics, instruments and monitoring — and will, over the course of the next year or so, become a practical reality at an affordable price.

Following my own advice in the main text (for once), I should consider software first, then the audio hardware, and only then decide on what sort of computer I need. To record audio as well as MIDI, I need an audio sequencer, of which the heavyweights are Emagic's Logic Audio, Mark of the Unicorn's Digital Performer, Opcode's Studio Vision Pro and Steinberg's Cubase VST, in alphabetical order according to manufacturer, you'll notice! This is not to suggest that other software is lightweight, but the guys I mention above have been around since the beginning of time, MIDI‑wise, and they should know a thing or two by now. I have to declare that I have been a Cubase user for a long time, therefore I'm biased. I have used all the other sequencers, but none of them have given me the grass‑is‑greener feeling yet, so for me Cubase VST is an easy answer, at £329 for the basic version, or £499 for Cubase Score with music desktop publishing. Cubase VST also seems to have the best plug‑in support at the moment, considering variety and price, and this would be another important factor in my decision. If I didn't have so much cash to spare, I'd look at the simplified versions of their main product lines which most software manufacturers offer, and which are worthy of consideration.

Next, I'd need a MIDI interface. I've managed for years on a couple of very simple 1‑In, 3‑Out units, and since my multitrack outputs MIDI Timecode (MTC) directly, I don't actually need a SMPTE/EBU timecode facility. If I did, however, I like the look of the Opcode Studio 64x, at £259, very much, and it's compatible with both Macintosh and PC.

For audio hardware at an affordable price point, I would probably have to choose the Korg 1212 I/O card, which has two analogue inputs and outputs, two S/PDIF digital inputs and outputs and eight ADAT optical inputs and outputs, all for £599. It isn't very exciting to look at, but it's an incredible piece of equipment at the price. It's compatible with Cubase VST, Digital Performer and Logic Audio, and I would expect other audio sequencers to be able to take advantage of its capabilities very soon. It is also compatible with hard disk recording and editing software such as Macromedia's Deck II and BIAS Peak. The drawback to the 1212 I/O is that it really needs to be linked to A/D and D/A convertors in both S/PDIF and ADAT formats, so that every input and output can operate in the analogue domain (Korg themselves make two boxes, one for A/D and one for D/A conversion, but these cost around £500 each). This would push the price up quite a lot. Also, if I didn't buy the extra convertors and I didn't have any other equipment with an ADAT‑format interface, the eight ADAT‑format channels would be of little use to me. If I decided on a PC as my computer platform, I'd also have to have a serious look at the Event Gina PCI card (Mac drivers were not available at the time of writing), which features two analogue inputs and eight independent analogue outputs, plus S/PDIF digital in and out. The output connectors are housed in a little breakout box, and the whole lot costs £499.

So now it's time to choose a computer — the controversial bit! Cubase VST is available in versions for Macintosh or Windows 95 (as is Logic Audio), and the Korg 1212 I/O is a standard PCI card and therefore suits either. I think it's still fair to say that the Macintosh is the more established platform at the moment for music, and software designers have been playing a catching‑up game with their Windows 95 products, so if I wanted to play safe I would go for the Mac. It would have to be a PowerPC model, of course, and I would be tempted to go for the latest and the best. The extra‑safe option, though, would be to go for a recently‑discontinued model, which will be at a knock‑down price and will also have been around long enough that any problems with it should have been noticed. Apple's Mac range is 'refreshed' often (some would say too often) and by keeping my eye on the Mac press I would be able to spot when another round of discontinuing and discounting was about to start (usually with announcements of a new range). If I could find one second‑hand or tucked away at a dealership, the recently‑discontinued 7300 would be a good bet. (Working on the principle that if it's good enough for Martin Russ, of Apple Notes fame, it's surely good enough for me!)

To buy a Macintosh, however, is to buy into a minority, so I would have to consider a Windows 95 computer, of which there is a bewildering variety. Although it should be possible to buy a PC simply on the specifications given by the software designer, I would be inclined to look at the big names, such as Compaq and Dell, since they have a reputation to protect if things should go wrong. I would also, unless I was absolutely certain that it was safe to do otherwise, insist on Intel Inside. It's the safe option, but I don't think the saving I would make on an alternative processor would be worth even a slight risk of incompatibility. As has been mentioned on other occasions in this magazine, it's worth paying special attention to the size of soundcard that can be accommodated. Apparently, some computers make installation a rather tighter squeeze than it should be.

Whichever computer I choose, if I'm going to be really sensible I'll only use it for music. Loading up a computer with extensions or drivers and installing games or demos from magazine cover CDs will ultimately lead to disaster. I'm afraid I'm not sensible — or rich — enough to have separate computers for music and for other tasks, but at least I make an occasional CD‑ROM backup of my system and applications disk, in addition to backing up my documents, so I can always get back to a state when my computer worked properly if I need to.

MIDI sequencing is important to me, but there are times when I would rather get away from MIDI and just record audio. In an alternative start‑over scenario I would go all out on a really good hard disk recording system, and there are two names that stand out for me. One is, of course, Digidesign's Pro Tools. Digidesign have been doing this for quite some time and they have obviously asked audio professionals a lot of questions. They've amassed nearly all of the answers and put all their knowledge and experience into Pro Tools version 4.0, and, more recently the 24‑bit Pro Tools 24 (reviewed on page 156 of this issue). A full Pro Tools system costs a lot of money; a Pro Tools Project system (which is not the highest level at which you can join the Pro Tools 'ladder') with eight inputs and outputs will cost around £5000 including the computer. The good news is that the entry point into Pro Tools isn't too expensive. Digidesign seem to be on a roller‑coaster ride of special offers at the moment and I wouldn't be surprised if things have changed when this gets into print, but at the time of writing the basic Pro Tools PowerMix software, which only runs on a Macintosh (check with your dealer for a list of approved models) has virtually all the full Pro Tools features and costs just a little over £700 — and you don't need to use a soundcard. Add another £100 to the price and you get (I'll stress at the time of writing) an Audiomedia III PCI card and D‑fx effects software. The Audiomedia III card only has two inputs and outputs (analogue and digital) but it can replay up to eight tracks simultaneously. Unfortunately, there is still no news on full Digidesign support for the Korg 1212 I/O.

The other product that has caught my attention, hard disk‑wise, is the Soundscape SSHDR1FS (it just trips off the tongue!) at £2000 plus PC computer. For this you get two inputs, four outputs, and up to eight tracks internally. It sounds great and has a reputation for reliability, probably because nearly everything happens within the Soundscape unit and hardly anything touches the computer.

Plug‑In Bonanza!

Firstly, what is a plug‑in? Plug‑in is an inelegant name for a piece of software that you can use in association with a major application, to provide additional processes and effects. You could, for instance, buy a compression plug‑in for your audio sequencer so that, in theory, an external compressor would not be needed. Plug‑ins come in a variety of standards, of which the best known are TDM, Audiosuite, Premier, VST and DirectX. TDM (named after Digidesign's Time Division Multiplex buss, which links their cards inside the computer) is compatible with Pro Tools and with other software that can address the Pro Tools hardware, such as Digital Performer, Logic Audio and Studio Vision Pro. TDM effects take place in real time and any parameter changes are instantly audible, and automatable. Audiosuite is also a Digidesign standard, but it works without the special TDM hardware. Audiosuite processes are file‑based, meaning that although you can get a preview of the effect, you can only hear the full result of the process by creating a new file and auditioning it. Premier is an editing application for moving images, made by Adobe, and as such you wouldn't expect to come across it much in Sound On Sound. However, the Premier plug‑in format has become something of a standard and is supported by Macromedia's Deck II, BIAS Peak, and others, and offers file‑based processing similar to Audiosuite. VST is, of course, named after Cubase VST and is similar to TDM in that effects take place in real time, but no additional hardware is required, given a suitable computer (and soundcard in the case of a PC). TDM and Audiosuite are Macintosh only, Premier and VST come in both Macintosh and Windows 95 versions. DirectX is Windows 95 only and is compatible with Cakewalk Music Systems' Cakewalk 6.0, Sonic Foundary's Sound Forge and Steinberg's WaveLab.

Just to whet your appetite here is a short selection of plug‑ins:

- Lexicon LexiVerb (TDM): a real Lexicon reverb inside your computer!

- Antares AutoTune (TDM and VST): no more out of tune vocals!

- Opcode Fusion:Vocode (Premiere and DirectX): fusing and morphing sounds together.

- Steinberg Magneto (VST): analogue tape simulation.