Zynaptiq’s innovative processors are claimed to address previously intractable problems with recorded audio.

Innovation doesn’t come easy, and sometimes requires bold steps from small companies who have fresh ideas and a willingness to think different. Zynaptiq are one such, and have carved out a niche for themselves by focusing on innovative digital processes that have yet to be realised by mainstream developers. Following the release of their de–reverberation software Unveil (reviewed in SOS July 2013: www.soundonsound.com/sos/feb13/articles/unveil.htm), Zynaptiq continue to upend the status quo with another pair of interesting utility plug–ins that not only offer a unique approach to conventional signal processing, but also tackle problems that previously were considered nearly impossible to solve.

Unfilter promises to help remove comb filtering in dialogue recording, as well as providing easy–to–use, intelligent corrective equalisation. Unchirp is designed to remove artifacts that arise from broadband noise reduction and lossy audio encoding, and can also restore transients lost or smeared as a result of over–compression. None of these tasks are easy to accomplish using conventional processors.

Big Balls

The graphical interfaces of both processors feature the unique spherical controls, referred to as Trackball Sliders, that are found on other Zynaptiq plug–ins. They function as vertical faders, and have a horizontal line along with a colour–coded border that accompany movement. I really like these: they’re not just easy to use with a mouse, but are fun to use on a multi–touch display, and make it very easy to see at a glance what your settings are. Both plug–ins sport a graphical display that provide live visual feedback of both frequency and amplitude of input (in magenta) and output signals (for Unfilter) or clean components (for Unchirp) in mint green. This colour scheme allows input and output data to be displayed simultaneously without feeling too cluttered to view.

Zynaptiq’s Unfilter can correct not only broadband tonal imbalances, but comb filtering too.Each display offers a Breakpoint Editor, which allow you to enter a number of points to either influence the intensity of the processing in certain frequency ranges, or serve as a dedicated EQ. There are a number of curve types that connect the nodes in either linear or smooth transitions or stepped edges and peaks/dips. Herein lies the power of these plug–ins, and their potential for creative sound design applications: in Unchirp, these nodes allow you to adjust the threshold and frequency amounts independently, offering greater control and flexibility. For sound–design applications with Unfilter it’s possible to use a mouse (or better yet your finger on a Slate Raven) to employ a real–time resonance filter during playback.

Zynaptiq’s Unfilter can correct not only broadband tonal imbalances, but comb filtering too.Each display offers a Breakpoint Editor, which allow you to enter a number of points to either influence the intensity of the processing in certain frequency ranges, or serve as a dedicated EQ. There are a number of curve types that connect the nodes in either linear or smooth transitions or stepped edges and peaks/dips. Herein lies the power of these plug–ins, and their potential for creative sound design applications: in Unchirp, these nodes allow you to adjust the threshold and frequency amounts independently, offering greater control and flexibility. For sound–design applications with Unfilter it’s possible to use a mouse (or better yet your finger on a Slate Raven) to employ a real–time resonance filter during playback.

To put Unfilter and Unchirp to the test, I assembled some pretty difficult test material to find out if they live up to Zynaptiq’s claims.

I Can See Clearly Now

At its heart, Unfilter is designed to estimate the frequency response of a filter that has been applied to a piece of audio, then apply a complementary filter to reverse its effects. It accomplishes this with what Zynaptiq call “real–time blind de–convolution” to analyse the signal and guess at what was done to it. In order to remove the applied filtering, Unfilter then creates a transfer function, which can be thought of as a ‘mapping’ of the frequencies that need to be manipulated in order to restore the signal to a more desirable state. The controls in the Process section determine the degree to which this function is applied.

Simple examples of corrections that Unfilter can make include compensating for overzealous high– or low–pass filtering that has removed too much bass or dulled the top end of a signal. It takes very little time for Unfilter to analyse the problem and apply corrective equalisation to bring the signals back to life.

More of a challenge is one of the more frustrating issues that can arise when working with location dialogue recording: comb filtering. This is often the result of signals from separate boom and lavalier mics being collapsed into a single channel, rather than split to separate tracks. As the sound reaches both mics at slightly different times, the resulting interference creates frequency peaks and troughs that wreak havoc on the recorded dialogue.

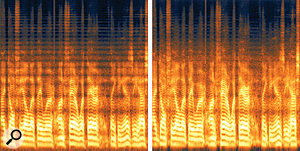

This might sound like an elementary recording mistake, but it’s something that you very often run into on low–budget films and reality shows. To test Unfilter’s ability to get rid of it, I used some location dialogue recorded for a reality television show. As can be clearly seen in the screenshot of the ‘Before’ spectrogram Before (left) and after (right): you can see from this spectrogram that the comb filtering which is clearly visible in the unprocessed audio as horizontal bands across the entire spectrum is significantly reduced once Unfilter has done its work., horizontal lines running through the entire frequency range are visible, and look like the effect of running a comb through smooth sand — hence the name ‘comb filtering’. The result is a very hollow and boxy sound that, in this case, was almost unusable. There are few conventional solutions that sound any good, and often you’re left having to apologise to the director or point a finger at the location mixer who got his wires crossed. You may be able to re–record the dialogue after the fact for narrative film, but documentaries and reality shows don’t have that luxury.

Before (left) and after (right): you can see from this spectrogram that the comb filtering which is clearly visible in the unprocessed audio as horizontal bands across the entire spectrum is significantly reduced once Unfilter has done its work., horizontal lines running through the entire frequency range are visible, and look like the effect of running a comb through smooth sand — hence the name ‘comb filtering’. The result is a very hollow and boxy sound that, in this case, was almost unusable. There are few conventional solutions that sound any good, and often you’re left having to apologise to the director or point a finger at the location mixer who got his wires crossed. You may be able to re–record the dialogue after the fact for narrative film, but documentaries and reality shows don’t have that luxury.

I have never before come across anything that can fix this, so at first I was very skeptical that Unfilter could achieve acceptable results. However, after some experiment with the Intensity, Resolution and Weighting sliders and slight modification of the Decay and Average settings, a very usable result was obtained, yielding a fuller sound without the hollowness the source suffers from. In most of the situations where I used Unfilter, I found that careful manipulation of the Intensity Bias breakpoints can determine success. Other important settings include the Learn function, which continuously updates the transfer–function estimate; the Noise option, which directs the Learn function to only use noisy signal components to derive its estimate; and a Weighting control that applies a Fletcher–Munson curve for a more natural–sounding result.

As can be seen in the ‘After’ screenshot, most of the mid–range filtering in the example has been undone. While the low and high frequencies in this example haven’t benefitted as much, dialogue mostly lives in the mid–range and suffers little as a consequence. You may not find that all dialogue problems will lend themselves to the same result, but we now have a tool that gives us a fighting chance, and after spending some time with the plug–in, I was often able to get results that would satisfy most clients.

Feeling Peaky

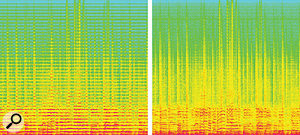

Another audio challenge Unfilter is designed to tackle is the presence of excessive resonant peaks. Zynaptiq supplied a sample recording that was virtually unlistenable. As with many difficult audio problems that come my way, I couldn’t for the life of me figure out how it could have gotten to the state it was in — it was that bad. The resonant peaks are clearly visible in Unfilter’s Graphic Display, and the comb filtering is even more dramatic in the spectrogram view. Another ‘before and after’ example: the left image shows an audio file rendered almost unlistenable by the prominent resonant peaks (horizontal red lines). Again, Unfilter has significantly improved matters (right).

Another ‘before and after’ example: the left image shows an audio file rendered almost unlistenable by the prominent resonant peaks (horizontal red lines). Again, Unfilter has significantly improved matters (right). The red line in this Unfilter screenshot shows the transfer curve it is applying to tackle the resonant peaks. While this particular example is not what you’ll see every day, Unfilter did an extraordinary job at smoothing things out and making the track listenable. It’s results like this that can often make the difference and make you a hero in the eyes of your clients. You won’t get positive results without spending some time with the plug–in, but the fact that you can improve these previously unsolvable issues at all clearly justifies the investment.

The red line in this Unfilter screenshot shows the transfer curve it is applying to tackle the resonant peaks. While this particular example is not what you’ll see every day, Unfilter did an extraordinary job at smoothing things out and making the track listenable. It’s results like this that can often make the difference and make you a hero in the eyes of your clients. You won’t get positive results without spending some time with the plug–in, but the fact that you can improve these previously unsolvable issues at all clearly justifies the investment.

It’s not just for fixing bad sound either: as already mentioned, Unfilter has sound–design applications, and can find a home just as easily in a mastering situation. Almost all recorded music can benefit from a little nip here and tuck there. Unfilter can add a sparkle to your mix in seconds with a mild twist of the knobs. It’s easy to overdo, but almost everything sounds better when passing through it. It’s not that you can’t do similar with your favourite EQ, but Unfilter allows you to get very quick results and wipe away whatever has been fogging up the sound.

Blurple Haze

Anyone who’s ever listened to a lo–res MP3 file or tried using noise–reduction software will recognise some of the common phrases used to describe the unwanted artifacts that these processes can give rise to: chirping, birdies, tweeties, warbling, underwater sound and so on. With MP3 encoding, the smaller the file size, the more aggressive the processing, and the more prominent the artifacts. There is no free lunch when you throw away 70 percent of the source data. Similarly, overly aggressive or inexperienced use of noise–reduction tools — not to mention poorly designed algorithms — often means that noise is removed only at grave cost to the wanted audio. There are conventional solutions to both these problems: compress the data less and increase the size of MP3 files, or back off on the amount of noise reduction. However, these are not much use if you’ve been presented only with the processed file! To the rescue comes Unchirp.

The first things that get lost with over–aggressive MP3 file encoding are high frequencies. Depending on the codec, they’re not only reduced, but removed altogether. Trying to restore some of that brilliance can be a fruitless task with conventional EQ, since there’s nothing to boost. Additionally, codecs that use any degree of brickwall filtering can induce ringing at the cutoff frequency point. To remedy this Unchirp offers two paths: Excite synthesizes new harmonics to replace the missing high frequencies, while Enhance uses psycho–acoustic processing to fool the brain into thinking that missing frequencies are actually present. Anyone who has used low–frequency enhancers to imply the root tone of the bass on small speakers knows how effective this approach can be.

In order to combat the chirping and twittering artifacts, Unchirp breaks these down into two categories by frequency range and offers a refined approach to dealing with them. The Musical Noise section deals with random rogue tones produced in the low and mid–range. A window slider controls the length of the artifact detection, and care must to be taken to set this correctly to avoid smearing frequencies and removing material that belongs. The Dechirping section, meanwhile, focuses on higher frequencies. There is an extremely helpful I/O Diff button in the Global Parameter section, which allows you to hear what exactly you are removing. A Side mode matrixes the input into a Middle and Sides signal and treats only the Sides material, while a Warmth slider adds random modulation to counteract the metallic ringing that sometimes results from removing chirping and musical noise. The Transients section, meanwhile, offers the ability to synthetically add missing transients and reduce smearing by ‘re–sync’ing’ existing transients.

I found an excellent use for Unchirp when trying to improve a music track supplied for a film trailer I was mixing. The song was an epic orchestral piece from a well-regarded stock music library. The client supplied an OMF, and once imported into my Pro Tools session I found that although the music track was labelled as an AIFF file, it sounded more like a bad MP3. What I could hear was the kind of crunchy distortion you get when hitting Waves L1 a little too hard, as well as significant amounts of what appeared to be twittering. My guess was that at some point the client downloaded an MP3 file and then just made an AIFF of it, but when I asked the music company to send a WAV file instead, it sounded almost as bad, so perhaps it was just poorly mastered. The Sync button was critical in tackling this, as it is designed to reduce transient smearing and add clarity to the sound. Too high a setting can reduce high–frequency content on sustained sounds and I found myself backing off to a setting of about 30 percent. I found the I/O Diff button very useful to ensure I was not removing any musical content along with the noise. The end result was a clean and crisp track, devoid of the distortion and artifacts that had plagued the source.

Magical Changes

A few minor niggles include the inability to Ctrl–Option–Command–right–click in Pro Tools to enable automation for individual parameters. I’d love to automate control point nodes in the Breakpoint Editor, but given the fact that you can add an unlimited number of them, it’s not practical to implement this. Also, presets are only available via the plug–in interface rather than the preset selector in the host application. The factory presets are only available in the plug–in itself, and not visible in a user-accessible directory to allow reordering and renaming in the Mac Finder or Windows Explorer (although you can re–save existing presets wherever you’d like if you prefer).

However, if you’re considering alternatives to Zynaptiq’s offerings, there really isn’t much to choose from. Previously, these problems required very careful and time–consuming manipulation with a combination of the best existing tools available, but often with barely noticeable improvement. Unfilter and Unchirp will not solve every problem thrown at them — and in some cases the improvements will only be subtle — but on the whole, given the right conditions, they can do a better job than anything else available. These are powerful tools, indeed, and used appropriately, can perform some pretty impressive processing.

About Zynaptiq

When I asked Zynaptiq co–founder Denis Goekdag about the origins of the company, he told me that “their goal is to solve issues that haven’t been solved yet”: not issues that haven’t been sorted out yet at universities, but real–world problems that audio engineers battle on a sometimes daily basis. Goekdag has a background as a guitar player, music mixer/producer and sound designer. This experience has given him a solid perspective on the kinds of tools musicians, producers and engineers need. He partnered with audio developer Stephan Bernsee, who previously founded Prosoniq and serves as Zynaptiq’s chief technical wizard. They had met while working on the Hartmann Neuron synthesizer. “I get to dream up the toys, and Stephan is the one who actually makes that happen,” says Goekdag.

The first product that bore the fruits of their efforts was Pitchmap, which allows for real–time polyphonic pitch processing. In late 2012 they released Unveil, the first — and arguably still the best — processor to successfully remove reverberation from a previously recorded signal. Unfilter and Unchirp are now bundled with Pitchmap and Unveil in the sensibly priced ZAP Bundle.

Pros

- Very powerful.

- There is nothing else that can do what these processors are capable of.

- Unique, user–friendly interface that lends itself to tweaking.

Cons

- Tackling difficult material requires a lot of trial and error, and familiarity with some unusual controls.

- Preset handling needs attention.

Summary

These plug–ins offer solutions to previously insoluble problems, and are a virtual necessity if you make a living trying to make bad audio sound better.

information

Eleven Dimensions Media +1 707 981 4833.