The five rackmounting members of the Digigrid hardware interface range are, from top, the DLI and DLS, which are specifically designed to connect with Pro Tools HDX systems; the versatile IOX which, with its plentiful analogue I/O, is intended to live in a live room; the IOC, which offers mainly line–level and digital I/O; and the IOS, which includes a built–in SoundGrid server and a broad palette of connection options.

The five rackmounting members of the Digigrid hardware interface range are, from top, the DLI and DLS, which are specifically designed to connect with Pro Tools HDX systems; the versatile IOX which, with its plentiful analogue I/O, is intended to live in a live room; the IOC, which offers mainly line–level and digital I/O; and the IOS, which includes a built–in SoundGrid server and a broad palette of connection options.

Two heavy hitters in the world of digital audio have come up with an intriguing new synthesis of hardware and software.

From string libraries to sealing wax, Sound On Sound has evaluated a great variety of products over the years. But as far as I can remember, we’ve never before reviewed a “scalable network infrastructure”. In fact, had anyone asked me what a scalable network infrastructure was, I’d have guessed it was something from The Thick Of It.

This particular scalable network infrastructure is a collaboration between two big names in digital audio: Waves, who have created the software component, and Digico, who supply the hardware. And although the three words in question make for a slightly indigestible mouthful, they do in fact describe the Digigrid system well.

A Digigrid system is made up of three types of physical element: computers running Mac OS or Windows; audio interfaces; and DSP servers. These are connected physically by Ethernet cables, and functionally by Waves’ SoundGrid Studio software, which handles routing, monitoring and audio processing. It’s an infrastructure because it’s designed to be permanently installed at the heart of a studio. It’s a network in the sense that its features can be shared and used by any connected computer (with the limitation that individual DSP servers can’t split their processing between more than one user). And it’s scalable because you can add more of the physical components at any time. If, for instance, you find yourself running out of audio inputs or DSP horsepower, you can simply buy or rent another Digigrid unit, power it up and attach it to the network. If more users want access to your Digigrid network, then as long as they have the software installed and licensed on their computers, they too can simply plug in a Cat 5e or Cat 6 cable.

Black Boxes

To start with the physical side of things, the current Digigrid range includes a total of seven Digico audio interfaces. Of these, four have no analogue I/O at all: the MGO and MGB are portable devices designed primarily to enable a laptop to hook into the MADI output of a live-sound rig or similar, while the DLS and DLI are intended to allow a Digigrid network to interface with Pro Tools HD, HDX and HD Native systems (see box).

Assuming you run a non–HD–equipped studio, that leaves a palette of three multi–purpose interfaces to choose from. With 12 mic/line inputs on combi XLR connectors, six line outs on quarter–inch jacks and four independent stereo headphone outs, the 1U rackmounting Digigrid IOX is designed to live in your live room, piping miked signals into the network and cue mixes back to the musicians. The IOC, by contrast, is intended for connection to other manufacturers’ preamps or A–D converters: it has two front–panel headphone sockets and two mic/line inputs, but the bulk of its I/O is on D–Sub connectors, providing 16 channels of AES3 digital and eight analogue line inputs and outputs, along with word clock and a single optical ADAT in and out.

Finally, the Swiss Army knife of the range is the IOS, a 2U device that offers all you need to set up a small–scale Digigrid system. It features eight mic/line inputs, eight line outs that are mirrored on D–Sub and quarter–inch jacks and a pair of front–panel headphone outputs plus MIDI, word clock and AES3 digital I/O. Like the Digigrid DLS, but unlike any of the other models, the IOS has a SoundGrid DSP server built in, so you can set up a complete Digigrid system with just an IOS, a computer and an Ethernet cable. The Digigrid IOS offers eight combi mic/line inputs and eight line outs, mirrored on jacks and a D–Sub connector. Connections with the SoundGrid network are made using its four RJ45 Ethernet sockets.

The Digigrid IOS offers eight combi mic/line inputs and eight line outs, mirrored on jacks and a D–Sub connector. Connections with the SoundGrid network are made using its four RJ45 Ethernet sockets.

If you have sufficient I/O already but want to add further DSP grunt, you have the option of three Waves hardware products: the portable SoundGrid Impact Server, the standard Server One and the more powerful Extreme Server. All three are, basically, embedded PCs. Live-sound engineers looking to connect digital consoles from Digico, Yamaha and Allen & Heath can also choose from a range of appropriate expansion cards for those desks. A Digigrid network can consist of up to 512 channels at 48kHz and below, or 256 at 88.1 and 96 kHz. These can be divided between inputs and outputs in any way you like, and controlled from any attached computer, but the ASIO and Core Audio drivers are currently restricted to 128 channels, so you can’t at present have a combined input and output count greater than this on any one computer.

Off Grid

Turning to the software dimension, what’s not included is any sort of recording or playback program. Instead, Digigrid is designed to be compatible with any DAW that supports ASIO or Core Audio, as well as with Pro Tools HD, HDX and HD Native. Its software functionality is split between two main components: a stand–alone application called SoundGrid Studio, and a plug–in called StudioRack. Users will also want to buy some SoundGrid–enabled Waves processing plug–ins in order to take advantage of the Digigrid DSP resources.

The StudioRack plug–in does not process audio, beyond allowing you to trim input and output levels. However, it is itself a plug–in host or ‘chainer’, with eight sequential insert slots that can accommodate any SoundGrid–enabled Waves plug–ins installed in your system. The clever part is that this chain of insert processors can run either natively, using your computer’s CPU resources, or remotely on the Digigrid DSP server. A simple drop–down at the top of the StudioRack window lets you switch just the instance that’s open, or all instances at once. If you open a project that uses StudioRack on a computer that isn’t attached to a Digigrid server, all instances will automatically be switched to native mode. So, for instance, you can track or mix a project at the studio with processing offloaded to the server, then take it away on a laptop for further work, then bring it back again, with minimal interruption.

Any StudioRacks that are in DSP mode also show up within the SoundGrid application, which is centred around a mixing utility called eMotion ST. The key advantage of this is that StudioRacks in DSP mode can be monitored directly, without the additional latency incurred by your DAW’s buffer settings. So if your singer needs to hear her voice compressed, equalised and reverberated, or you’re a guitarist playing through Waves’ GTR amp simulator, you can hear the processed sound without any distracting delays. What’s more, with a little bit of configuration, it’s possible to have input monitoring switched automatically when you engage Record in your DAW.

Getting Started

For this review, Waves and Digico loaned me a Digigrid IOS along with temporary licences both for the SoundGrid software and a selection of Waves plug–ins. Costing £2700$3760 without factoring in the plug–ins, computer or DAW software, this is pretty much the smallest and simplest DSP–based Digigrid system with I/O that you can buy: the scalability from this point is all one–way!

Connecting everything up is supremely simple, and even if you don’t need the networking side of things, the advantages of Ethernet as a connection protocol are obvious: cables are cheap and plentiful, and cable runs can be pretty much as long as you like. The review IOS had a rather annoying cooling fan, but production units will be fitted with a fan controller which should improve matters; Digico sent me one to retrofit at the end of the review period, and it did indeed eliminate most of the noise. In any case, it’s feasible to hide the IOS away in a machine room, as all of its features are controlled remotely from the SoundGrid Studio utility. Hardware metering is minimal, so the only thing you’d really miss are its headphone outputs (which are, incidentally, bloody loud!).

Digico describe the IOS’s mic preamps as “award–winning”, but although I like the fact that phantom power can be switched individually and gain set to within half a dB from SoundGrid Studio, they are more functional than flashy. The gain range is restricted to the usual 0–60dB found on most budget interface preamps, there are no pads or high–pass filters and, sonically, they are transparent rather than characterful. They’re perfectly usable, but I’d have though most serious studios would want to augment them with something a bit more sexy.

It’s worth pointing out that in this sort of configuration, the IOS works perfectly well as a standard ASIO interface. All of its inputs and outputs were visible and accessible in my DAW software, and buffer sizes right down to 32 samples are supported, so if you want to keep things simple, it’s possible to run a recording session quite happily without using the Mixer or StudioRacks features of SoundGrid Studio at all. However, Windows users should note that there is no MME or WDM driver for SoundGrid or the IOS. It thus doesn’t show up as an option in the Playback or Recording pages of the Windows Control Panel, and you can’t route the output of non–ASIO programs such as iTunes into it.

Silly Wizard

When you first install the SoundGrid software, it runs a Wizard which attempts to configure the system and routing to your needs. I suspect I must have done something wrong at this point, because the DSP server within the IOS did not get added to my system, and I spent really quite a long time trying to figure out why I couldn’t use many of the features of SoundGrid Studio. Once I’d visited the Setup page and added it as a Server in the System Inventory’s Device Racks, it sprang to life and I had no further problems. The System Inventory page lets you see what devices are connected to a Digigrid network. In this case the Digigrid IOS is supplying both my Server and my Hardware I/O Device.

The System Inventory page lets you see what devices are connected to a Digigrid network. In this case the Digigrid IOS is supplying both my Server and my Hardware I/O Device.

Although SoundGrid Studio boasts a commendably large, clear and friendly graphical interface, however, configuring a SoundGrid system manually is not for the faint–hearted. This is especially true if you need to venture into the Patch page, where you’ll find four separate routing matrices that interact in ways which are not always obvious. It would be easier if the large, clear and friendly graphical interface could be resized — I don’t like to think about the amount of scrolling you’d have to do in a large Digigrid patching setup with multiple I/O units and servers. Fortunately, this should be the sort of thing you can forget, once set, and the preset arrangement worked fine for me.

Second That eMotion

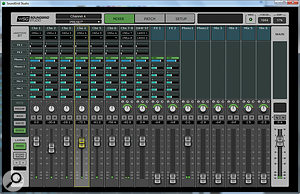

Most of your time with SoundGrid Studio is spent in the eMotion ST Mixer page. As well as utility areas for configuring the preamps and setting channel input and output routings (which are mirrored in the Patch page), eMotion ST provides two mixer ‘layers’. Typically, inputs that you are recording into your DAW project would be accessed via the StudioRacks layer, which we’ll come to in a minute, while everything else is visible in the main Mixer layer.

As well as the Preamp and Route pages mentioned above, this has two main modes. Rack mode gives you access to eight insert slots per channel, each of which can be populated by an individual SoundGrid–enabled plug–in. This opens up a number of possibilities. For instance, plug–ins applied to input channels process the sound prior to recording, so if for instance you want to record guitar through an amp simulator or bass through a compressor, you could do so here. Alternatively, if for instance you wanted to use a metering or monitor calibration plug–in across your outputs without affecting the mixdown within your DAW, you’d insert it on an output channel.  The eMotion ST window has two layers. In the main Mixer layer, shown here, you can use the Sends page to create up to eight separate cue mixes, as shown; alternatively, the Preamp, Rack and Route buttons select other views.

The eMotion ST window has two layers. In the main Mixer layer, shown here, you can use the Sends page to create up to eight separate cue mixes, as shown; alternatively, the Preamp, Rack and Route buttons select other views.

The other main mixer mode is Sends, which is fairly self–explanatory, and makes it easy to create up to eight different cue mixes routed to different destinations. A nice touch is that selecting an output channel on the left side of the mixer screen ‘flips’ the faders so that they control the aux send level to that destination rather than the main output. The whole mixer turns blue as a friendly reminder that you’ve done this.

Racks & Racks

The eMotion ST mixer’s StudioRacks button is, by default, greyed out. To make it active, you need to have open a DAW project containing one or more StudioRack plug–ins that are set to run on the SoundGrid DSP server.

The StudioRack plug–in window consists of several functionally independent sections. At the bottom left are input and output faders; these have metering superimposed, and there is also a third meter labelled Dyn which can report the gain reduction being applied by any of the dynamics plug–ins inserted within that instance of StudioRack. Plug–ins themselves are inserted within the column of eight slots to the right of this area. A miniature version of the plug–in interface appears within the slot, and a further area to the right can display the full GUI for whichever of the plug–ins is currently selected. Above the faders are visible four assignable rotary controls, each of which can connect a knob on an attached MIDI controller to the plug–in parameter of your choice.

Perhaps the most important group of controls, however, are those found at the top left of the StudioRack window. The Processing pop–up lets you switch the current instance, or all instances in your DAW project, between native and DSP operation. As I’ve already mentioned, StudioRacks running in native mode don’t show up in eMotion ST, and within the plug–in window, the eMotion Monitoring controls are greyed out unless in DSP mode.

To set up low–latency input monitoring, you first need to tell the StudioRack plug–in which physical input to your DAW it’s controlling, and give it an appropriate name. For example, supposing you were recording a stereo keyboard track into Pro Tools via line inputs 5/6 on the interface, you’d need to make sure to select that input pair within the StudioRack plug–in on the keyboard track, and enter a suitable name within the plug–in. Setting all this up for a large session could be a bit of a faff, but with DAW templates and so on it shouldn’t be something you need to do often.

Once you’ve done this, each StudioRack plug–in can be switched between Playback and Input modes. In the former, it takes as its input the recorded signal from the DAW track; in the latter, its signal is taken directly from the selected audio interface input, bypassing the DAW’s input buffer. This makes it possible to monitor the input through any processing plug–ins applied within the StudioRack plug–in but with minimal latency. Pressing the Grp button adds the open instance to a group that can be switched in one go. This is handy for situations where you are working with a lot of inputs, but not nearly as handy as the Auto option. Making this work requires adding Waves SoundGrid StudioRack as an HUI controller, but this is a matter of moments to set up, and once it’s done, StudioRacks in Auto are automatically switched to Playback during playback, and Input in stop or record. Neat.

Finally, hitting the Sends button on the StudioRack plug–in displays all eight eMotion ST aux sends for that channel, so you can adjust its contribution to each cue mix without leaving your DAW. For the most part, in fact, the choice of whether to use eMotion ST or to work entirely in your DAW depends on your preferences. If you want to add or modify plug–ins in a StudioRack, you’ll need to do it in your DAW; if you want an at–a–glance overview of all active StudioRacks and their contribution to your cue mixes, eMotion ST is the place to do it. Otherwise, most of the actions you’d need to take during recording can be performed equally well in both. The other main eMotion ST view is StudioRacks. In this mode, any StudioRack plug–ins within your DAW project that are currently set to DSP mode are visible as mixer channels, allowing you to create low–latency cue mixes from inputs.

The other main eMotion ST view is StudioRacks. In this mode, any StudioRack plug–ins within your DAW project that are currently set to DSP mode are visible as mixer channels, allowing you to create low–latency cue mixes from inputs. The StudioRack plug–in running in DSP mode in Pro Tools. As Auto monitoring mode is active and the transport is stopped, it is currently processing the signal arriving at its input, bypassing the DAW’s input and output buffers. The Sends panel is open, and its settings mirror those for the relevant channel in eMotion ST’s StudioRacks page.

The StudioRack plug–in running in DSP mode in Pro Tools. As Auto monitoring mode is active and the transport is stopped, it is currently processing the signal arriving at its input, bypassing the DAW’s input and output buffers. The Sends panel is open, and its settings mirror those for the relevant channel in eMotion ST’s StudioRacks page.

From a mixing point of view, the plug–in chaining functionality in StudioRack has some neat advantages. Entire StudioRack configurations can be saved and reloaded as presets that are independent of your DAW, so in a studio where multiple users who favour different DAWs collaborate, this would make it much easier to transfer settings and projects. It’s also possible to automate individual plug–in parameters, and each instance of StudioRack has a side–chain input that can be shared among any or all of the plug–ins it hosts. On the down side, if you want to perform an offline bounce within your DAW, you need to switch all StudioRacks to native mode. Otherwise, as I found to my cost, you’ll get silence.

Who Benefits?

As I’ve already mentioned, the review system supplied by Waves and Digico is pretty much the simplest complete SoundGrid configuration available that incorporates a DSP server. It’s interesting to contrast this system with something like Universal Audio’s Apollo, which is similarly priced and likewise offers high–quality DSP–based plug–in processing, but is much more narrowly targeted at the home– and project–studio market. In comparison with eMotion ST, the UA Console utility has several obvious limitations: plug–in processing can only be switched globally between the record and monitor paths, and there’s no real integration into your DAW’s mixer. Console–based cue mixing can’t be done from within the DAW, and if you want to employ the same plug–in configurations at the mix stage, they need to be manually re–loaded into your DAW. Yet for this market, UA’s approach also has some major advantages. Because it doesn’t offer the same scalability or flexibility, it’s far simpler to learn and use; and the hardware elements of the Apollo systems ooze glamour in a way that Digico’s utilitarian black boxes don’t.

If equipping a slightly more upmarket single–room studio, you might ask yourself what a Digigrid system would offer as an alternative to a Pro Tools HDX rig based around, say, an HDX Core PCIe card with an HD Omni interface. In terms of bang for the buck, at least, the Waves/Digico solution looks very tempting, delivering more I/O and quite possibly more DSP plug–in resources for less than half the price, with its scalability opening up more varied prospects for future expansion. On the down side, setting up low–latency monitoring and cue mixing using StudioRacks and eMotion ST is significantly more complex and slower than doing it all within the Pro Tools HD mixer. The HD Omni also builds in a powerful and sophisticated monitor controller, something which is currently absent from the Digigrid range. (You do, of course, have the option of combining Digigrid with something like an HD Native system, for the best of both worlds.)

One further way in which SoundGrid differs from the Avid and UA systems should be highlighted. Both of the latter run their plug–ins on dedicated DSP chips, and the plug–ins themselves are coded in such a way that their DSP load is always known in advance. This means there’s a fixed limit to the number of plug–ins that you can run on an HDX card or Satellite, but that within that limit, performance is guaranteed. The same is not true of the SoundGrid DSP servers, which are basically embedded PCs that allocate their CPU resources dynamically. This is a more flexible approach in some ways, but can’t guarantee a particular level of performance; the manual warns that using over 80 percent of the resources of an individual server risks causing dropouts and other problems.

Up Scale

The Digigrid system does have its attractions for a small, single–user studio, then, and I particularly like the option of being able to add additional I/O simply by hooking up extra IOX units. On balance, though, I’m not sure it would be my own first choice in such a context. When you consider the power of modern computers and the latency figures that can be achieved using interfaces such as RME’s Fireface 802 or Apogee’s Ensemble Thunderbolt, the idea of introducing the extra complexity of a SoundGrid server in order to run Waves plug–ins outside your DAW seems less compelling. If hooking up a multi–channel interface to a native DAW gives you plentiful plug–in power and low enough latency, there’s not much reason to add further complication. SoundGrid is a deep product that takes time to get your head around, and in the heat of a session, I’d feel slowed down by the whole StudioRack and eMotion ST apparatus.

However, the advantages of the Digigrid system become more apparent when you consider applications that exploit its scalability and networking features. For example, an increasing number of studios now follow a cost–effective model where multiple mix and programming suites are built around a smaller number of shared live rooms. The Digigrid IOX looks a tempting option for many studio applications, not least because of its four built–in headphone sockets. Place a couple of IOX interfaces in the live areas, run a few Cat 5e cables about the place and shove a server in the machine room, and you make it possible to run sessions in any live room from any of the connected control rooms. Users would be able to share not only hardware facilities but also StudioRack processing chains, no matter whether they’re Mac Logic acolytes or PC Cubase devotees. Likewise, it’s not hard to see the advantages that Digigrid and SoundGrid could bring to larger educational institutions, broadcasters or post–production and voiceover facilities. And there’s the advantage of close integration with a variety of popular live–sound desks.

The Digigrid IOX looks a tempting option for many studio applications, not least because of its four built–in headphone sockets. Place a couple of IOX interfaces in the live areas, run a few Cat 5e cables about the place and shove a server in the machine room, and you make it possible to run sessions in any live room from any of the connected control rooms. Users would be able to share not only hardware facilities but also StudioRack processing chains, no matter whether they’re Mac Logic acolytes or PC Cubase devotees. Likewise, it’s not hard to see the advantages that Digigrid and SoundGrid could bring to larger educational institutions, broadcasters or post–production and voiceover facilities. And there’s the advantage of close integration with a variety of popular live–sound desks.

There are, of course, plenty of other networked audio systems around, but the StudioRack element marks out Digigrid as being clearly different from these rivals, giving users the ability to employ almost any plug–in from Waves’ vast catalogue as a live signal processor for front–of–house and monitor mixing, as an insert to print to disk, in the monitor path and at mixdown. I have to say, though, that its appeal in a multi–room context would be greater if the Digigrid hardware range included a dedicated control–room unit with talkback and monitor control. As things stand, it’s not immediately clear how best these features might be implemented. I mentioned this to Digico, and apparently I’m not the first user to have pointed out the need for such a unit, so hopefully future developments will yield fruit in this area.

In its present state, there are also limitations to the software side of Digigrid which will limit its appeal in some quarters. Perhaps the most obvious is the lack of any support for surround sound. And although one of the selling points of the SoundGrid system is that it is open to third–party plug–in manufacturers, at the time of writing, the first third–party offerings from Brainworx, SPL and Eventide were not yet commercially available. It remains to be seen how much take–up there will be for SoundGrid among other developers.

Conclusion

It’s obvious that both Waves and Digico have invested considerable development resources into the Digigrid range, and for a product that’s still in its commercial infancy, it struck me as impressively mature. The hardware might not be sexy, but it’s reassuringly solid, and the ASIO driver proved as robust in practice as any I’ve encountered. I didn’t run into a single bug, crash or other oddity during the entire review period, and the consistent, clear and user–friendly design of the SoundGrid software goes a long way to mitigate for its complexity. For simple home– and project–studio environments with just one control room and one live room, I’m not sure that the benefits of the Digigrid system outweigh this complexity. However, if you need to equip a multi–room facility, integrate a modern digital live-sound rig, cater for the differing tastes of several engineers, or even if you just want to leave open the possibility of future expansion, Digigrid deserves serious consideration.

Alternatives

A number of audio–over–Ethernet protocols have been developed, and manufacturers such as Focusrite and MOTU have taken advantage of these to develop scalable systems that have applications in the studio. However, the way in which the Digigrid system runs Waves plug–ins on DSP servers at minimal latency is, as far as I know, unique.

Multirack

The Digigrid concept has close connections with Waves’ Multirack system, which is designed to allow live–sound engineers to use Waves plug–ins on their mixes. At its simplest, Multirack is a plug–in chainer and host which can be run natively on a Mac or PC, with audio piped in and out either using an appropriate multi–channel audio interface, or the built–in Firewire or USB connections on digital desks such as the Behringer X32, PreSonus StudioLive and so on. However, there’s also a SoundGrid–enabled version, where the plug–ins themselves run on a SoundGrid server, with the Mac or PC acting mainly as a controller. This provides guaranteed low–latency performance, which is of course hugely important in a live–sound context, especially with complicated multi–speaker PA systems.

In both cases, chains of Waves plug–ins created using Multirack can be opened in the StudioRack plug–in, and vice versa. This means that a recording engineer working on a multitrack recording of a live show that was mixed using Multirack can access all the effects and processors that were used by the front–of–house engineer; and, conversely, that the studio mix engineer can make his or her plug–in chains available as starting points to use in a live show. The potential benefits of this integration are obvious, especially when you consider the challenge of bringing to the stage a heavily produced album with lots of spot effects.

Incidentally, those with long memories might recall that the Digigrid system isn’t the first to run Waves plug–ins on a remote DSP server connected via Ethernet. Almost 10 years ago now we reviewed their APA 32: just like the current generation of DSP servers, this was basically a PC embedded in a rackmounting box and fitted with a very noisy cooling fan. It also had some basic networking features. Unlike Digigrid, however, the APA processors were purely intended to boost DSP power at mixdown, in the manner of TC’s Powercore or UA’s Satellite, and did not feature any audio I/O or low–latency input monitoring.

Digigrid & HDX

The way in which you use StudioRack plug–ins is similar in all native DAWs, but a different approach is needed to get SoundGrid working with Pro Tools HD, HD Native or HDX. Pro Tools accesses Avid’s HD hardware and its associated DSP processing using its own driver. This, unsurprisingly, cannot talk directly to a SoundGrid network.

Integration between Digigrid and HDX is achieved by attaching one or more Digigrid DLS or DLI units to a spare Digilink expansion socket or to an HD or HDX card, in the same way as you might attach a third–party A–D converter unit. Once this is done, plug–ins running on the SoundGrid DSP server are treated as if they were external hardware effects units with their own plug–in controllers: a Pro Tools Hardware Insert ‘plug–in’ handles routing to and from the server, whilst the StudioRack plug–in operates in ‘I/O Insert’ mode, configuring the processing that is applied. In this sort of system, the only I/O that is handled by Digigrid consists of connections between Pro Tools and the SoundGrid server, so there is no low–latency input monitoring — that is handled by Pro Tools, as usual.

I did not have the opportunity to test a system that used Digigrid and HDX hardware, so can’t tell you how well this works in practice.

Pricing

Because Digigrid is a modular system, it can be configured in many different ways. The SoundGrid software is included with all hardware units, but Waves plug‑ins will need to be purchased separately. Pricing for the Digigrid interfaces is as follows (including VAT):

Digigrid MGB and MGO: £1260$2000 each.

Digigrid DLI: £840$1280.

Digigrid DLS: £2035$3120.

Digigrid IOX: £1860$2640.

Digigrid IOC: £2040$tbc.

Digigrid IOS: £2700$3760.

Pros

- A scalable system with something to offer everyone from serious home studios to large multi–room complexes.

- SoundGrid Studio offers flexible cue mixing and the ability to monitor and record through Waves plug–ins at minimal latency.

- Can be used simultaneously by multiple engineers, even if they’re running different DAWs.

- StudioRack provides some neat plug–in chaining facilities, and the ability to run in native mode means projects can be worked on away from the host system.

- Plug–in chains can be transferred seamlessly between studio and compatible live–sound setups.

Cons

- The complexities of the Digigrid system are present at all levels, but some of its advantages will only be apparent in large setups.

- There are gaps in the initial hardware product range, most notably for a monitor controller.

- No third–party plug–ins available yet, and no surround support at present.

- Though it works well on Windows, there’s no MME or WDM driver to support non–ASIO–compliant applications or the Windows OS itself.

Summary

Waves and Digico have drawn on their shared expertise to create a versatile and well thought–out modular product range. The scalability and networking features aren’t relevant to everyone, and come at a cost in terms of simplicity, but they mean you’ll never outgrow a Digigrid system.

information

Sonic Distribution +44 (0)8455 002500