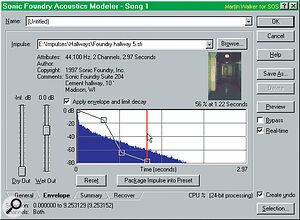

Here is the Acoustics Modeler window inside Sound Forge. The auditorium sound currently running in real time takes more than 100% of the computer's processing power with a Pentium 166MMX — but who said realism was easy?

Here is the Acoustics Modeler window inside Sound Forge. The auditorium sound currently running in real time takes more than 100% of the computer's processing power with a Pentium 166MMX — but who said realism was easy?

If you want to recreate the sound of a particular hall or studio live room, why not capture its essence and then use this to treat your music? Sonic Foundry's new software makes it all possible. Martin Walker samples the results.

If you want to recreate the sound of a particular hall or studio live room, why not capture its essence and then use this to treat your music? Sonic Foundry's new software makes it all possible. MARTIN WALKER samples the results.

Acoustics Modeler is a new PC plug‑in from those clever people who designed Sound Forge (and for those who don't know, the name is not a misprint, but the American spelling of 'Modeller'). Rather than launching yet another reverb plug‑in, Sonic Foundry have provided a way to capture the sound of real acoustic spaces, such as actual halls, rooms and churches, reduce each of these to an 'acoustic signature', and then allow you to use these to add the effect of the chosen environment to any audio recording. Since the signature is of a real environment, the result can be uncannily real. However, Acoustics Modeler doesn't stop there — the same system can capture the signature of a music signal emerging from another piece of equipment, such as an existing reverb unit, or an expensive condenser mic, to simulate passing your music through the same device. It can even be used in a totally off‑the‑wall fashion, by creating signatures from synth patches, or indeed any recorded sound, and using these to process other sounds, for some totally unique results. Appetite whetted? Let's take a closer look.

Software Support

The Envelope page allows the user to create gating effects, and impose a volume envelope to change the recorded decay characteristics of the chosen environment.

The Envelope page allows the user to create gating effects, and impose a volume envelope to change the recorded decay characteristics of the chosen environment.

Since Acoustics Modeler is compatible with Microsoft's DirectX plug‑in standard, it can be accessed from any application that supports DirectX, such as the 'big three' PC MIDI + Audio sequencers (Cakewalk Pro Audio v6, Cubase VST PC v3.5, and Logic Audio v3.0), as well as audio editors such as Sound Forge v4.0 itself, and WaveLab v1.6. The installation routine checks that you have DMSS (DirectX Media Streaming Services) on your PC, and if not, offers to install it for you. Copy protection is taken care of via a unique serial number found inside the front cover of the manual, which must be entered just once, but the CD‑ROM will be required again if you download any free software update from the Sonic Foundry web site, just to check your honesty. As with all audio software, your PC must be fairly powerful, but Acoustics Modeler needs more power than most for real‑time operation. You will need a Pentium, but a Pentium Pro is recommended, along with Windows 95 or NT 4.0 (or later). Due to the large amount of data processing, 24Mb of RAM is required, along with several hundred megabytes of temporary storage space on your hard disk.

Once installed, the program can be accessed from any DMSS‑compatible host, and basic operation is simplicity itself. You just choose an Impulse file (which contains the acoustic 'distillation'), either by typing in its name, or using the Browse button to call up a list of such files provided with the package — there are a wide variety on the CD‑ROM. These normally have a Sonic Foundry Impulse file extender (.SFI), although choosing a normal WAV file can also produce interesting (although often unusual) results. The natural sounds include not only standard environments like halls, churches, and auditoria, along with hallways, tunnels, and bridges, but also extend to forests and caves. On the equipment front, there is a range of mics (including condenser, dynamic, and ribbon), guitar amp spring reverbs, and a selection of real reverb plates. However, nothing escapes the microphones of the Sonic Foundry team, and even showers, bathrooms, kitchens, and their new office have been pressed into service (before the furnishings went in, by the sound of it!).

Once you start to think of these Impulses as simply acoustic events, changing over time, you start to realise why there are also folders containing the sound of running streams, footsteps, synth sweeps, and even drum loops — any changing sound can be mapped onto an audio signal, to give all sorts of weird acoustic vocoder‑like effects.

Sounding It Out

I grabbed a reverb preset from my Alesis Midiverb 4: the upper plot show the test‑ tone frequency sweep, along with the two spikes (extreme beginning and end). The lower plot shows the WAV file recorded from the output of the Midiverb 4 — the Impulse is extracted from this.

I grabbed a reverb preset from my Alesis Midiverb 4: the upper plot show the test‑ tone frequency sweep, along with the two spikes (extreme beginning and end). The lower plot shows the WAV file recorded from the output of the Midiverb 4 — the Impulse is extracted from this.

Once you have chosen an Impulse, you simply preview the sound as with any other plug‑in, either in real time, or letting the program build a preview. Since Acoustics Modeler takes a lot of processing power, there is a five‑way Quality/Speed setting which defaults to position 3 — the lower the setting, the less processing power is required, and the more likely you are to get a glitch‑free preview. However, the drop in quality is significant: position 1 is in mono, and position 2 often sounds quite 'grainy'. As you increase the Quality/Speed setting up to 5, the spatial characteristics become more pronounced. The top position is obviously the setting to use when treating your sounds, but many people will lack sufficient power to hear these in real time, especially with the larger environments, whose decay times are longer.

Acoustics Modeler should come into its own for special effects — if you find yourself wondering what that synth pad would sound like in the bowels of a cave, within a huge forest, or even underwater, now's your chance to find out for real!

Since what you hear from Acoustic Modeler is the effect of a real 'space', at a predetermined distance, you will normally only want to use the 'Wet' signal, as real reverb already includes the correct proportion of Dry and Wet sound. However, vertical sliders are provided so that you can set up your own balance if you wish. There are four pages of software settings: General, Envelope, Summary, and Recover. On the General page, besides the Dry and Wet controls (which are duplicated on several of the other pages), there are five additional horizontal slider controls (see the main screen on the first page of this article). Response Width defaults to 50% (the normal stereo response, as initially recorded in the Impulse), but you can reduce it all the way down to 0% for a totally mono result, and increase it 'beyond the speakers', all the way to 100%, although this does sound rather unnatural at extreme settings. Response Delay alters the relative timing between the Dry and Wet signals (‑500ms to +500ms). Again, the default position is in the middle, with other positive values delaying the wet signal, and negative ones producing pre‑delay, with the dry signal after the wet, for special effects. There are two shelving filters, each with a +/‑ 15dB range; the low shelving one can be set between 15 and 15000Hz, and the high shelving one between 20 and 20000Hz.

The final horizontal slider on the General page also features a graphic display from inside the main display of the Envelope page (see screenshot on page 120). If the checkable option box marked 'Apply envelope and limit decay' is selected, you can drag the vertical red line on the graphic display (the decay time) to chop off the decay portion of the sound and create gating effects. The actual volume envelope can also be modified, by creating and dragging any number of graphic envelope points. Although you can use this for special effects, it can also be a good way to manage those Impulses with longer decays (less PC processing power is needed if the modelling is applied to a truncated version of the sample). The Reset button returns the envelope to its default (flat out) setting, and the 'Package Impulse into Preset' button combines the Impulse with your current control settings, and saves it. The Envelope page also displays a small graphic showing where the Impulse was recorded (if a graphic was attached to the Impulse file).

The Summary page simply shows a larger version of the same picture, along with any descriptive notes that have been saved with the Impulse. The fourth and final page is Recover, and this is where you can convert your own WAV files into Impulses (the acoustic signature is 'recovered' from the WAV file). This is one of the main beauties of this program — you aren't restricted to what the manufacturer provides. Several test signals are provided on the CD‑ROM; they all consist of a full‑frequency sweep signal, with a single narrow pulse recorded a few seconds before the start of the sweep, and again after it finishes. The idea is that you set up a loudspeaker in your environment, replay the test signal, and then record the resulting sound, using a stereo microphone (or crossed pair), into your soundcard, using any stereo recording application (such as Sound Forge itself). The distance between the loudspeaker and the microphone will determine the wet/dry balance (this is real life, after all), and the room will add its sound to the test signal.

Once you have a stereo WAV file, this is 'topped and tailed', to remove all but the initial spike (for timing information), the sweep (containing the frequency response against time, including the early reflection information), and the decay right up to the start of the second spike (to ensure that the program knows what happens after the sweep has finished, to calculate the remainder of the reverb decay). Then you enter the Recover page, point to your recorded file, to the test tone that you used to create it, select an output filename, and then press the Recover Impulse button (see the screenshot below). The Impulse file is then written as a new WAV file in just a few tens of seconds, depending on its length.

The Proof Of The Processing

Once you have recorded your test tone output, you simply load it into the Recover page, and press the Recover Impulse button, and yet another acoustic environment is saved to your hard disk.

Once you have recorded your test tone output, you simply load it into the Recover page, and press the Recover Impulse button, and yet another acoustic environment is saved to your hard disk.

The Impulses provided with the program give a huge range of quality sounds, with a wider spread of reverbs than you could create in the majority of rackmount reverb units. Some of the really huge ones, such as 'State Capitol Dome', are wonderful, although more mundane settings such as multi‑storey car parks still provide exciting results. More unusual sources, such as 'Barn Silo', gave a useful reverb, but with an almost vocoded after‑echo. You do have to be careful to avoid overload, and normalised input signals can cause problems unless you pull down the Wet Out slider a bit — just adjust it so that the output play meters never clip.

My Pentium 166MMX showed occasional readings of 2000% processor overhead, but quite often there were still no audible glitches, which makes me wonder just what the processor overhead indicator is reading. However, when they did occur, the gaps in the waveform lasted a second or so, although they never crashed Sound Forge. The audible results seemed far better than the processor overhead would indicate, and Sonic Foundry do mention various buffering tweaks that managed to get rid of my gapping in most cases.

As with all products that push back the boundaries, there are a few initial teething troubles with host applications other than Sound Forge itself. Apparently, both WaveLab and Cakewalk can crash and stutter during real‑time playback, and WaveLab only shows one of the four available pages. Philippe Goutier (the designer of WaveLab) sent me a pre‑release patch during the course of this review, which cures both these problems, and which should be generally available shortly. Expect speedy updates to all of these problems — thankfully, manufacturers of real time plug‑ins seem to be pulling together, as compatibility is the major lure for future customers.

To find out just how much information could be extracted via the Impulse, I grabbed the output of a reverb patch (see screenshot on page 122), and then created an Impulse from it. Comparing an 'Impulse‑treated' sound using Acoustics Modeler with the actual reverb unit sound was very interesting; despite the limitations of the average PC soundcard, the sounds were very close, and it should prove an ideal way of storing a selection of unique reverb effects. Of course, it is far less convenient than using a real‑time external reverb unit, but then not everyone can have access to a £2500 Lexicon!

Summary

This is an extremely clever program, with a wide variety of potential applications. Sadly, its high processing needs make it unlikely to run successfully in real time for all but shorter Impulses, unless you have a powerful processor (Sonic Foundry are being realistic in recommending a Pentium Pro). This will probably preclude it from use inside many people's MIDI + Audio sequencers, although you could still treat the required track off‑line, and then use the permanently altered version. This would also allow you to always use the highest quality settings, for best audio results.

I suspect that some people will buy this program to use as a bit of a gimmick, but it's far more than that — the ability to accurately recreate the sound of any real environment is an extremely powerful one, especially for TV or film work (see the 'Applying More Thought' box). Indeed, once you start trying out some of the more unusual impulses provided, it becomes obvious that the sound‑changing possibilities go far beyond reverbs. Being able to impose the frequency and decay characteristics of one sound on another is a bit like vocoding, although the modulator needs in this case to be a shorter 'hit', rather than a continuous second signal, as processing requirements rise with the Impulse length. The beauty of Impulses is that if you want a particular setting, you choose it from nature, rather than attempting to work out what knob settings to dial in on a rack unit. Acoustics Modeler is excellent value, and comes into its own for special effects — if you find yourself wondering what that synth pad would sound like in the bowels of a cave, within a huge forest, or even underwater, now's your chance to find out for real!

Doing It The Hard Way

Simulating real spaces using normal reverb algorithms can often prove frustrating. What if you find that a drum kit sounds wonderful in a certain stone cellar, or in the church hall that you use to practise in? If you attempt to recreate this environment using a standard rackmount reverb unit, you'll probably end up suffering from terminal frustration. When reviewing effects units, I've often tried to duplicate the sound of one reverb patch on another unit, and although you can quickly get fairly close when listening, for instance, to a single drum hit, as soon as you compare the two patches with another sound source, you realise how much is still different — the changing frequency response of the reverb tail as it decays and the spread of reflections all conspire against you in duplicating a reverb 'sound'.

Some units provide a Room Size parameter, which is a good start, but you've still got to know enough about acoustics to adjust all the other parameters correctly (or have golden ears). Although controls for decay time, along with low‑ and high‑frequency Damping, can be set fairly quickly by ear to approximate the size, surfaces and materials used in the room, the grouping of initial reflections can make or break the overall effect. All of these parameters are incorporated into the complex algorithms locked away inside the DSP chips of the reverb unit. The algorithms on high‑end units such as those made by Lexicon are world‑renowned for their clarity and smoothness, but every manufacturer will have a subtly different sound.

Acoustic modelling does offer a way for musicians with powerful computers to gain access to extremely realistic environments. The only alternative is to get out the microphones and record your sounds at the appropriate venue — this may arguably produce more hi‑fi results, but at the expense of flexibility and easy access. It also assumes you have the cash to re‑hire the Royal Albert Hall every time you need to add a touch more reverb to that drum sound!

Applying More Thought

Once you get past the initial 'gee‑whiz' factor, Acoustics Modeler would seem to have many additional uses, apart from providing a software reverb with presets named 'Royal Albert Hall', 'Ronnie Scott's with lots of people crammed in', and 'Taj Mahal at sunset'. It would seem ideal for film and TV post‑production, where Impulses could be captured on location, for adding to overdubbed dialogue later in the studio. Sound effects (foley) could still be produced in the studio, but again with acoustics captured previously from the actual set or location.

One thing this plug‑in can't do is model non‑linear systems, such as valve enhancers and guitar stomp boxes. This is because a different Impulse would be produced at every input level, since the frequency response is constantly changing, depending on the level presented to the input. I was surprised at some of the results given by using standard WAV files as Impulses. Rather than simply producing novelty effects, the process often created sounds that were a strange amalgam of the two sources. I suspect that creative users of Acoustics Modeler won't just use it to add a modelled 'space' around existing tracks, but also to twist new textures from their music, or to create new standalone samples.

Pros

- Wide variety of realistic reverb effects.

- Realistic price as well.

- Ability to capture your own sounds.

Cons

- Heavy‑duty processor needed for real‑time operation.

Summary

An extremely clever plug‑in that provides a host of unique reverb sounds, as well as many bizarre treatments.