Pianoteq 7 loaded up with its new New York Steinway D. Users of previous versions will feel right at home: all the important changes are under the largely unchanged surface.

Pianoteq 7 loaded up with its new New York Steinway D. Users of previous versions will feel right at home: all the important changes are under the largely unchanged surface.

Pianoteq 7 introduces new morphing features and an even more realistic modelling engine.

It’s been fascinating to follow the progress of Pianoteq, by French company Modartt, since its debut in 2006. In case you haven’t heard of it already, it’s a virtual instrument specialising in acoustic and electric pianos, mallet instruments, harps and harpsichords that’s based on principles of acoustic modelling, as opposed to sample replay. That makes it computationally intensive, potentially, but also laughably small in its installation footprint on your computer: still only around the 50MB mark (which by my calculations makes it about 0.0007 the size of something like Synthogy’s Ivory II) and requiring only 256MB RAM.

This latest version, Pianoteq 7, adds two new features. The first is a morphing and layering engine. Morphs allow you to create hybrid instruments that don’t exist in reality by blending aspects of two or more donors. Layering is a simpler and more familiar concept, but can make for a different kind of sophistication. The second headline addition is a new piano, a brand spanking American Steinway Model D ‘SPIRIO|r’. That’s an update of the already no‑expense‑spared 8’11” model D, and it adds motorised‑key replay facilities. The real thing would cost you over $200,000 to buy new.

Perhaps just as important, though, is yet another refinement of the underlying modelling engine, which promises to improve the sound of the entire existing instrument line‑up. ‘Double polarisation’ takes account of string vibrations that can emanate in any direction into the soundboard, and is said to provide more complexity, a three‑dimensional character, and supports acoustic piano bass notes that can sustain as long as a couple of minutes.

Morph The Cat

I was excited to try the new morphing features in the Pro version I had on test, and I must say they did not disappoint: they enable a new kind of sound design.

Working in a dedicated (and detachable) panel you load presets for any of your instruments into slots that have accompanying mute and solo buttons, and which have a horizontal travel fader that controls the intensity of that ‘ingredient’ (Modartt’s terminology, suitably culinary perhaps). There will also be a vertical crossfader between the slots, which acts as a macro for the slot faders, and determines the relative dominance of each preset in the morph. It’s not especially pretty but it could hardly be quicker or more intuitive.

The new morphing feature is like some kind of sonic DNA splicing, letting you create entirely new instruments by melding together existing ones, in different proportions. Here, a bizarre mix of grand piano, hand pan, and Hohner Electra‑Piano. The user interface takes on styling that’s appropriate to the most dominant ‘ingredient’.

The new morphing feature is like some kind of sonic DNA splicing, letting you create entirely new instruments by melding together existing ones, in different proportions. Here, a bizarre mix of grand piano, hand pan, and Hohner Electra‑Piano. The user interface takes on styling that’s appropriate to the most dominant ‘ingredient’.

Morphing between presets then proves to be a fascinating thing. I liked taking one of the pristine grands, for example, and morphing it with a rough, inharmonic Hand Pan or Steel Drum. Strange and wonderful chimeras would emerge: pianos with bizarre overtone structures or muted decay phases. Everything is up for grabs: Wurlitzer/xylophone clashes, or tubular bell/virginal mash‑ups. And if that weren’t enough, you can add up to eight ingredients in a morph, for really strange, genetically scrambled hybrids with lots of mothers and fathers.

Aside from being fundamentally a very intuitive way of deriving new sounds, morphs must surely be one of the most creatively fruitful. Tweaks of voicing or design parameters for individual instrument’s could already yield interesting distortions of them. However, with morphing you’re messing about apparently much deeper in the mathematical engine room, and the results can end up far removed from any of the starting‑point ingredients. Excitingly so, I thought, and yet still musically persuasive and inspiring, as opposed to weird or ugly.

There are some really useful supporting features. A Random button can give pleasant surprises, whilst Flatten makes any given morph into a new preset in its own right, with the potential to become an ingredient in a new morph. There’s also a ‘Freeze’ feature which lets you select parameters to be excluded from a morph: that helps overcome difficulties with switch‑ or toggle‑type parameters (like Effects enables) that can’t be smoothly transitioned. Finally there’s a ‘Smooth x2’ option to run two Pianoteq engines in parallel, which doubles CPU use but achieves entirely smooth morphs even if there are parameter step‑changes, via crossfading.

In comparison to morphing, Layering might seem a less interesting proposition, but that’s not necessarily the case. Up to three presets can be involved in a layer, and as well as useful orchestral‑leaning combos (harp+celeste for example) you can take identical pianos, say, and set up octave stacks (nice for some Latin styles, and useful for the opening of the Liszt first concerto), phasey detunes, or combos of compressed dry sounds and spacey reverberant backdrops. And with Pianoteq Standard or Pro it’s possible to use the Note Edit feature to dovetail the output levels of two instrument layers across a pitch region, to have one sound in the bass crossfading to a different one in the treble, for example.

Taking the place of typical sample library mic perspectives is a multichannel virtual miking model which lets the user design their own captures, or fall back on a range of established starting points such as AB and ORTF.

Taking the place of typical sample library mic perspectives is a multichannel virtual miking model which lets the user design their own captures, or fall back on a range of established starting points such as AB and ORTF.

So, Spirio

As for the new Steinway, yes, it’s very nice. Complex and commanding, and with a typically 21st‑century bright and shiny character, in contrast to the more ‘woody’ European D. Perhaps not the most immediately attractive piano I’ve ever heard, but then real Steinway Ds often aren’t either. As with most Pianoteq pianos it comes in more than a couple of dozen preset alternatives.

And I’m wondering, actually, if I shouldn’t have written this next finding as the very first thing in this review: Pianoteq 7 does sound better than previous versions, by quite a long chalk. It’s really good.

There has sometimes been a certain character associated with modelling systems like Pianoteq, where all the wonderful stuff could be tempered by a note of artificiality or sterility, like an aural equivalent of not‑quite‑convincing movie CGI. In version 7 that seems to have gone for good. The acoustic pianos (and actually it was only ever the acoustics that were affected, which no doubt points to what a hellishly complicated business it is to model them) now sound entirely convincing to me. On the odd occasion I thought they were still a bit too squeaky clean the Condition parameter was on hand to loosen things up and add the modelling version of an analogue synth’s ‘slop’. I’ll also take this opportunity to put in a word for the less well‑known Steingraeber, Grotrian and Bluthner pianos — these sound particularly fine in version 7.

Other standout instruments include the electro‑acoustics and Clavinet (which has proper rocker‑switch interface and note‑off twangs), pretty much all the mallet instruments and the metal pans. That was already true of earlier versions. The more recent Hans Ruckers II harpsichord is energetic, playable and useful, at least as good as most sampled alternatives, and the various historical pianos are charming, evocative and seriously enlightening for appropriate repertoire.

It helps with these and all other sounds that the on‑board effects quality is high: there are three slots you can load up with three‑band EQs, choruses, delays, amp simulators and more, and a final convolution reverb. What seems to be a master‑level EQ is more sophisticated than that, working directly on the physical model. I’ll also praise the simple but devastatingly effective Dynamics slider, which controls the difference in audible level from the extremes of MIDI velocity. Natural‑sounding presets often have it set around 36dB, but at lower values pianissimo playing ends up far closer to fortissimo in level, so you get a kind of ‘pronounced hush’, a special kind of compression that can be a real boon in a busy mix.

Pianoteq 7 does sound better than previous versions, by quite a long chalk. It’s really good.

Teq The High Road

Pianoteq 7 ultimately presents an easy task to a reviewer: it’s a brilliantly refined virtual instrument that builds in meaningful ways on already formidable strengths, and is a pleasure to work with. Even if the idea of modelling doesn’t quite appeal, or you were not convinced by older versions, a demo of Pianoteq 7 will be worth a try. For acoustic piano duties it’s now virtually impossible to distinguish it in quality from huge single‑piano sample libraries, and the degree of sound design flexibility the modelling approach allows can easily make them look like dinosaurs.

It’s also so much more than a piano: indeed, you can legitimately use it for a wide gamut of sounds that doesn’t include piano at all. That’s to say nothing of all the other benefits, including top‑class support of MIDI pedal inputs and no less than 10 types of piano/harpsichord/harp pedal behaviours, polyphonic aftertouch support for clavichord sounds, the best sympathetic resonance in the business, velocity calibration for controller keyboards, Native Instruments NKS compatibility, and support for Linux as well as Mac OS and Windows. It’s not even especially CPU‑intensive, by today’s standards. A great update to an already excellent software instrument.

Packed & Ready

One really crucial difference from many sample‑based competitors is the somewhat flexible nature of actually buying Pianoteq. It’s changed a bit over the years, and this is the current scheme.

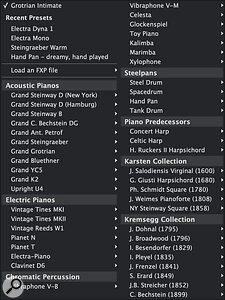

The array of sounds available within Pianoteq is quite astonishing: a veritable virtual museum’s‑worth of desirable instruments.To begin with, there’s a choice over the three available versions. Stage (€129$149) is the simplest, which exposes relatively few sound design parameters, and does not support the new morph/layer feature. Standard (€249$299) does, and further lets you tweak all aspects of the modelling engine, gives per‑note adjustment of volume, detune and attack, and adds advanced tuning, 3D multichannel mic modelling, and import of external reverb impulse responses. Finally, Pro (€369$449) extends the per‑note voicing capabilities to 30 parameters, allows manipulation of individual overtones, and adds support for sample rates up 192kHz.

The array of sounds available within Pianoteq is quite astonishing: a veritable virtual museum’s‑worth of desirable instruments.To begin with, there’s a choice over the three available versions. Stage (€129$149) is the simplest, which exposes relatively few sound design parameters, and does not support the new morph/layer feature. Standard (€249$299) does, and further lets you tweak all aspects of the modelling engine, gives per‑note adjustment of volume, detune and attack, and adds advanced tuning, 3D multichannel mic modelling, and import of external reverb impulse responses. Finally, Pro (€369$449) extends the per‑note voicing capabilities to 30 parameters, allows manipulation of individual overtones, and adds support for sample rates up 192kHz.

And then, as if your purchase had got you into to some kind of swanky virtual piano restaurant, you have to choose what sounds you want. These are offered as ‘packs’, and for the Stage version you get to choose any 2, for Standard, 3, and for Pro a total of 4, from the 21 that are currently available. Generally a pack covers one manufacturer or instrument type, so there are separate packs for the Steinway model Ds and model B, Bechstein D 282, Petrof 275, Steingraeber E‑272, Blüthner Model 1 and so on. Sometimes they’re more of a ‘bundle’, like Electric Pianos (encompassing two Rhodes and a Wurlitzer), the Hohner Collection (Clavinet D6, Electra‑piano, Pianet N and Pianet T), or the two Historical Pianos collections. There are some free add‑ons too, incidentally, including a good CP‑80 electro‑acoustic, some early grand pianos, a cimbalom and tubular bells.

Selecting from such an extensive menu may sound daunting, but it’s helped enormously by the fact that every pack is in fact built into every version of Pianoteq, and you’re only ‘unlocking’ the ones you end up choosing. That lets you play all others in a demo fashion, with various pitches missing, but enough remaining to form a meaningful impression. You’re at liberty to buy more packs at any time too, at €49$59 each. For those with deep pockets that just want everything, a €700$899 ‘Studio’ bundle gives you Pro, all currently available packs, and any new packs released within a year of purchase.

Alternatives

4Front’s TruePianos has sometimes been hailed as a Pianoteq alternative, but whilst it seems to utilise modelling technology, has a similarly small installation size, and is pleasantly affordable, it offers nothing like the same scope or refinement. Alternative modelling systems can be found in hardware, such as Roland’s SuperNatural‑based instruments, but otherwise the main competitors are sampled.

Pros

- Notably improved sound quality: Modartt’s claims of three‑dimensionality and increased complexity are completely justified.

- The line‑up of instruments (and official endorsements from their original manufacturers!) is even more formidable than before.

- Morphs and Layers open up user‑friendly (and unexpectedly effective) pathways for sound design.

- Offers flexibility that most sample libraries could only dream of, despite a delightfully tiny installation size.

Cons

- Instrument pack bundling can look a bit miserly, given the riches on offer, and purchasing many more soon adds significantly to the initial outlay.

Summary

Another important stride forward for this fine modeller of acoustic and electric pianos, clavinets, harpsichords, mallet instruments and harps. Pianoteq 7 retains brilliant playability and responsiveness, but takes the fundamental sonic complexity of its entire range of instruments, and the potential for sound design, to new heights.

Information

See ‘Packed & Ready’ box. Prices include VAT.

See ‘Packed & Ready’ box.

Test Spec

- Pianoteq 7.0.3.

- Apple MacBook Pro 16‑inch with 2.4GHz 8‑core Intel Core i9 and 32GB RAM.

- Mac OS 10.15.7.