Korg's Trinity workstation has, like their earlier instruments, become virtually an industry standard — but far from resting on their laurels, the company have upped the ante still further with the new Triton. Derek Johnson and Debbie Poyser provide an exclusive hands‑on review.

The Korg name is forever entwined in the minds of hi‑tech musicians with the word 'workstation'. Having basically invented the mass‑market keyboard workstation with 1988's M1, which introduced the magical pairing of sequencer and synthesizer, Korg went on to cement their workstation reputation with a series of very capable machines, culminating in the most impressive workstation of the last three and a half years: the Trinity.

This silver dream machine, incorporating synthesizer, effects and sequencer, was rightly hailed as "probably the first affordable instrument that truly earns the tag 'music production workstation'" (Gordon Reid, SOS Trinity Plus review, December 1995/January 1996). It has a staggering array of features, and where the standard facilities leave off, the options kick in. A fully‑loaded Trinity really is a studio in a box — dedicated Trinity owners could add sample RAM, physical modelling synth boards, a multitrack hard disk recording option and digital interfacing. Musicians flocked to buy it, even at its premium price, lured by the feature set, the polished, high‑quality sounds, and innovative ideas like the huge touch‑sensitive screen which gave new meaning to the overworked term 'user friendly'. It's a hard act to follow.

Yet the modern pattern of regularly refreshing ranges means that follow it Korg must, with a workstation that has to go one (or several) better, correcting Trinity's faults, refining its user interface still further, adding new features, and, if it forgoes any Trinity facilities, subtracting only those which won't be missed. Can Triton pull it off and keep Korg at the top of the workstation heap?

Sea Changes

It's easy to see why Korg chose 'Triton', the name of a minor sea‑god in Greek mythology, for Trinity's successor. It's similar enough to make it obvious that they are of the same lineage, it has classical overtones, and the fact that said sea‑god was given to frolicking about with a three‑pronged trident echoes Trinity's 'triple' theme!

Similarities between the two machines continue to an extent with their appearances. Like Trinity, Triton is silver, but where Trinity's panel is smooth brushed aluminium, the Triton has a subtle sparkle finish that's very contemporary, if not quite as expensive‑looking (or as easy to clean!). The touch‑screen still dominates, but the sci‑fi art‑deco moulding that lifts it from Trinity's panel is gone, replaced on Triton by a less dramatic rectangular frame. There are some extra buttons, and even some knobs — but we'll save those for later.

At the back, perhaps the most significant change is the presence of six audio outputs (compared to Trinity's four). A paucity of individual outs was one of Trinity's few weaknesses, so it's good to see the issue addressed, at least to this extent, on Triton. Two audio inputs, with level control and mic/line switch, have also been added, and though the most obvious use for these is to pipe material into Triton for sampling — yes, sampling — they can also be used to bring in external audio for treatment by Triton's effects. (Trinity effects could not be employed in such a way without the HDR option installed.) Staying with the back panel, another new arrival is a direct Mac/PC serial interface. This feature has been appearing for some time on more modestly priced keyboards and modules, but is new on a Korg deluxe workstation.

Whereas the Trinity offered four independent outputs (two of which doubled as the main Left + Right outs), Triton offers four individual outs in addition to the L‑R outputs. Also new is the serial port for direct connection to a Mac or PC.

Whereas the Trinity offered four independent outputs (two of which doubled as the main Left + Right outs), Triton offers four individual outs in addition to the L‑R outputs. Also new is the serial port for direct connection to a Mac or PC.

Sound Architecture

A very significant difference between Trinity and Triton is the new machine's 62‑note polyphony. This really might turn Trinity owners greenish with envy, as Trinity offers only 32 notes — a decision for which reviewers took Korg to task. The company were adamant, however, that their priority with Trinity was to ensure the finest sound quality and most comprehensive effects implementation, so resources were directed towards these areas rather than towards providing masses of notes. So what's changed? Have Korg compromised their original vision to provide the extra notes? It seems not.

Korg's pre‑Trinity AI2 (Advanced Integrated) workstations made use of 32‑note polyphonic tone generator ICs which also incorporated filtering and effects. Two chips yielded 64‑note polyphony. For Trinity, things changed: to achieve the sound quality they wanted, Korg used discrete chips for different functions — samples, filtering, DSP — on a processor board. Achieving 64‑note polyphony in Trinity would have required two of these boards, which would have been "phenomenally expensive" according to Korg UK. Since Trinity's launch, however, Korg have been beavering away to achieve Trinity sound quality on one chip. The resulting 32‑note polyphonic TG96 IC has been three years in development, incorporates everything, and has made Triton's increased polyphony possible. As in earlier years, they simply use two chips, though in the case of Triton this produces 62‑note polyphony for reasons connected with its built‑in sampler. Multitimbrality remains at 16 parts.

In other respects, Triton's sound‑generating side — now called Hyper Integrated (HI) synthesis — should be as familiar to seasoned Korg synth users as Trinity's. (For a fuller description of the Korg method, check out SOS's two‑part Trinity review, mentioned earlier.) Briefly, just like Trinity, Triton is sample‑based: at the bottom level of sound creation are raw sampled waveforms. Up to two of these can be combined (as 'oscillators') in a Program, and up to to eight Programs can be layered, split or crossfaded in a Combi, which can also be multitimbral if desired. There's also the option of velocity‑switching between the two oscillators in a Programplus, if you can handle it, the ability to velocity‑switch between two waveforms in each oscillator, with no adverse implications for polyphony. Oscillators may also be delayed, treated to random tuning (where each time an oscillator sounds, its pitch is slightly different) for recreating the effect of an analogue synth with unstable tuning and, new to Triton, reversed, so that a waveform plays backwards. Strangely, the Trinity's reverse factory waveforms have made their way over to Triton even though the latter has this facility.

The raw waveforms in a Program can be treated using a familiar collection of subtractive synth parameters that, again, have much in common with Trinity's. The basic signal path of oscillator, resonant filter and amplifier is augmented by two LFOs, plus a variety of envelope and modulation options. In most cases, Triton has more parameters, and certainly more modulation options; the filter, for example, is actually meatier and more resonant than Trinity's, but there don't seem to be quite as many options when it comes to filter types. Excellent effects processing is the icing on all stages of the cake.

Like the standard Trinity, Triton comes with two banks each of Programs and Combis, both banks containing 128 sounds, overwritable with user edits. Korg have upped the PCM waveform count, though: Triton has 425 multisamples, plus 413 single drum samples for use in kits, as opposed to Trinity's 375 multisamples and 258 drum samples. Trinity users will be keen to know how far Triton's voice selection differs from that of their own machine. Many of the basic waveforms seem the same, and many Programs also sound very similar across the two machines, though lots have been re‑named for Triton. Combis appear to have been largely reprogrammed. You'll certainly find the staple bass/vibes and bass/piano splits, piano/string layers and classic Korg orchestral combinations, plus more fairy‑like atmospheric pads than you could shake a wand at, just as with Trinity, but they seem to have been re‑done from scratch for Triton.

Korg's intention to give the Triton more dance appeal emerges in various new Combis and Programs, though not really in the raw waveforms; even so, there is a collection of DJ‑friendly scratches, yells and hits, many of which were included on Trinity. Some of the dance‑focused Combis are great fun, and a few make excellent instant tracks, too! The dual arpeggiator — more later — offers a wide selection of dance rhythms, suitable for producing quick bass lines or drum patterns.

Some might question one or two of Korg's decisions: abandoning digital connectivity options at a time when the world is becoming increasingly digital seems almost perverse.

Though Trinity was not General MIDI‑compatible in its original form, a disk full of GM sounds could be loaded for GM compatibility. Triton goes further, with a GM sound bank already on board. This is divided into sub‑banks providing the alternate voices required for XG and GS, the Yamaha and Roland extended GM formats. There's even a sequencer mode for playing Standard MIDI Song Files direct from disk, though since Triton doesn't support all GS/XG sound maps and messages, Korg don't guarantee that all GS/XG data will always play back correctly. (We tried a few XG files and they played back properly.) GM Programs, by the way, can be freely used in Combis and sequences.

Anyone unfamiliar with Trinity's sounds can rest assured that they are beyond reproach in terms of quality — and this extends to its successor. The presets are imaginatively and creatively programmed, and source samples have excellent clarity and sparkle, with basically undetectable loop points. The Korg bods who worked on voicing apparently used Jupiter Systems' acclaimed Infinity sample‑manipulation software to ensure the smoothest loops.

Just For Effects...

Trinity set its own standard in effects sophistication, allowing flexible processing similar to that achievable with a rack of outboard. Specifically, it provides more 'Insert' processing — effects that can be dedicated to a single sound, such as distortion on a lead guitar — than competing workstations, plus two global 'Master' processors. And it offers straightforward graphic routing of those effects, so best use can be made of them.

On Trinity, effects had a so‑called 'Size' (either 1, 2, or 4), which reflected their complexity and the consequent demands they made on the Trinity's DSP chip. As long as the total Size of all active effects did not exceed eight, you were free to set up effects in a variety of combinations (eg. two Size 4 effects, one Size 4 and two Size 2, up to eight Size 1). At first glance, it would appear that effects have been trimmed on Triton: its two Master effects are augmented by five Insert effects, as opposed to Trinity's maximum of eight.

In fact, Triton's effects have merely been implemented differently. Triton does not have any 'Size 1'‑style effects (except in chained pairs — see the 'Triton Treatments' box), and simply offers a list of Insert effects to choose from, most of which are equivalent in DSP terms to Trinity's old Size 2 effects, but with a selection of more complex effects which equate to Trinity's old Size 4 effects, and are dubbed 'double‑size' in Triton terminology. It's possible to use two double‑size effects at one time, along with a normal effect, so really there's more Insert processing than on Trinity, since the total permitted Size (to talk in Trinity terms again) on Triton equals 10 (five size 2, or two size 4 and a size 2). Furthermore, Trinity only allowed the maximum eight Insert effects to be used in a multitimbral sequence setup, limiting Insert effects per Combi to three (though still with a total Size of eight). Triton, however, can use all five Inserts in sequence setups and in Combis. Nevertheless, if you'd like the option to use eight size 1 Insert effects per sequencer setup, you might lament the Triton reduction to five, even though the Triton's are more complex.

Effects variety has been increased, though, especially in the Master department — Trinity had 14 Master effects to Triton's 89, and the two Master processors are not restricted, as in Trinity, to reverb/delay for one anmodulation for the other. Triton's Master effects can be any of the 89 available — which, incidentally, are identical to the 89 normal‑sized Insert effects. 'Double‑sizers' aren't available as Master effects.

On the Insert front, Triton offers 101 effect choices (including 13 double‑size effects available only to Inserts 2, 3 or 4) to Trinity's 100. However, 29 of the Trinity Insert effects were the small 'size 1' ones, so overall Triton does better. The selection of Insert effects has been changed very slightly.

As on Trinity, a Master EQ is available, but it's been improved: where the original machine offered a fixed high/low EQ that was more like a tone control, Triton features an effective, fully adjustable 3‑band EQ with swept mid. This is well worth having.

Effects routing, too, has been improved on Triton: the effects edit windows now have better graphics that make it even more obvious what is being sent where. Programs, or Programs in a Combi or Sequence, can be routed to the main or individual outs (and the individual outs can be grouped in pairs for stereo operation), or to the Insert effects. The Insert effects can themselves be routed to other Insert effects, or to the same choice of main or individual outs as the Programs, making it easy to send individually treated Programs to their own external mixer inputs, if required. The send controls to the two master effects are found in the Insert effect edit pages, just as on Trinity.

Worthy Of Notes: The Sequencer

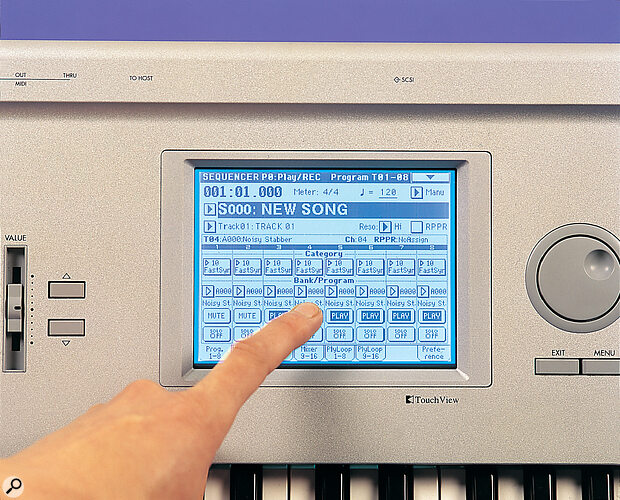

Triton's sequencer will be familiar to Trinity users, being an almost identical, largely linear 16‑track device, offering real‑ and step‑time recording with 192ppqn timing resolution, a 40‑240bpm tempo range, a wide choice of time signatures, and straightforward corrective quantisation facilities. Almost the same editing options are available — erase, copy and bounce track; erase, delete, insert, copy and move measure; create and erase control data; quantise; shift/erase note; and modify velocity. New for Triton is Repeat Measure, which allows the user to specify how many times a measure should be played, instead of making multiple copies — a sensible addition.

The Triton's sequencer is similar to that of the Trinity, but is expanded to store over 100,000 notes and 200 songs.

The Triton's sequencer is similar to that of the Trinity, but is expanded to store over 100,000 notes and 200 songs.

Other enhancements have been made, too: note capacity is over 100,000, to Trinity's 60,000, and the Triton sequencer's ability to loop individual tracks (so that a couple of bars of drums and eight bars of bass, forexample, could loop for the length of a song without the need for manual copying) will increase Trinity owners' envy. Maximum sequencer Song capacity is now 200, and there's a very good new Cue List mode which allows the playback order of up to 100 Songs to be specified. Korg suggest that small sections such as verses, choruses and bridges could each be saved as Songs and the Cue List used to lay out their order and repeats to make up a track — a finished cue list can be converted to a Song.

Many Trinity users apparently wished for real‑time phrase triggering from the keyboard, and their wish has been granted on Triton in the shape of RPPR (Real‑time Pattern Play/Recording). This allows musical phrases or patterns (up to 100 user patterns per Song) to be assigned to keys and triggered in real time, perhaps for live performance — though the result can also be recorded into a sequence. Triton even has over 100 preset drum patterns, though we found, on the review unit, that there was a slight lack of range, with blocks of adjacent patterns seeming very similar to each other. This may be to facilitate real‑time triggering of related patterns in different combinations, like 'variations' on auto‑accompaniment instruments.

Another new presence in the Sequencer is the Template Song. There are 16 user Templates designed to speed composition by allowing you to save favourite sets of voices, drum sounds and effects, to come back to time after time when creating a new Song — a good idea. Korg also provide 16 preset Templates, filled with voices and effects settings suited to particular musical styles (including, on the model we reviewed, Techno, Drum & Bass, New Age, and Rock) but not, perhaps strangely, matching arpeggiator settings or drum patterns.

The powerful sequencer is very easy to use, not least because of the superb screen. Perhaps a time display, which would be useful for checking how long a given Song is running, could be added at some point?