JBL's new studio monitor system, the LSR32, represents a radical departure in their approach to the design and technology of loudspeakers. Hugh Robjohns lends them his ears...

There was a time (when policemen were middle‑aged, and sequencers controlled only the flashing lights at discos) when I would rather have used a pair of cocoa tins and a bit of old string to coax a mix from a master tape than suffer the aggressive, coloured 'American Sound' of older JBL monitors. Tough as old boots they may be, punchy and directional in PA systems they certainly can be, but point a pair at me in a studio control room and I would have begged for the cocoa tins every time! But that was then... now, JBL have caught up with all that is good and worthwhile in modern loudspeaker design practice — and they have even added a few new twists of their own.

The LSR32s are the first in a new range of monitor loudspeakers based around JBL's new‑found approach to speaker design, which involves careful analysis and control of the total radiated sound of the speaker, not just the on‑axis sound. This attention to the spatial response of the loudspeaker system as a whole lead to the moniker LSR or 'Linear Spatial Reference', and it represents a significant leap forward in perceived sound quality.

The design aim is twofold, and has been set out in a white paper available on JBL's professional products web site, www.jblpro.com, in the 'Technical Notes' section (Volume 3, Number 2). The primary goal was to create a 'listening window' in which the user can move around and receive consistent sound quality, ideally with stable and accurate stereo imaging. The second aim is that off‑axis sound projected above, below and to the sides of the loudspeaker should have as smooth and consistent a frequency response as possible with a gentle tailoring of HF energy levels. This tailoring is based on the psychoacoustics of how we react to the combination of direct, reflected and reverberant soundfields within a listening environment. Off‑axis sound hits the side walls, ceiling and floor, and bounces on to the listener as the first strong reflections, before going on to create the reverberant sound. Consequently, the spectral balance of these reflected sounds can have a very significant effect on the perception of the overall quality and clarity of a loudspeaker system.

There is nothing earth‑shatteringly new in this approach to speaker design — many of the more reputable hi‑fi manufacturers and the best of the professional monitor builders have been aware of the importance of the off‑axis contributions of their loudspeakers for a long time, and have designed and built their models accordingly. Indeed, most of the references quoted in JBL's LSR white paper list AES papers from the '70s and '80s. However, analytical techniques have improved enormously since then, and computer analysis and modelling allow the testing of theories and optimisation of the design prior to building mechanical prototypes for the fine tuning.

The real advantage of the LSR approach of getting the total spectral power emitted by the loudspeaker balanced properly is that the resulting loudspeakers work better in real rooms. They tend to have less perceived coloration, larger usable listening areas with good consistency of sound and wider, more stable stereo imaging — all critical qualities in a monitor loudspeaker design.

LSR32

So, to the first of JBL's new LSR products, the LSR32. This is a passive three‑way system, described by the manufacturer as a midfield monitor. It is certainly far too big to be used as a nearfield, with cabinet dimensions of 635x394x292 mm and weighing in at over 21kg (47lbs). With boxes of this type, and with drivers spaced as these are, a certain minimum distance is required for the sound from the drivers to become fully integrated — hence the midfield label.

The simple rectangular cabinet encloses a 50‑litre volume which is vented to the front through what appears to be an elliptical flared port, but which JBL's white paper refers to as a "linear dynamics aperture"! The dual‑flare design is claimed to reduce port compression and eliminate port noise (a breathing noise accompanying LF peaks and known in the trade as 'chuffing').

Moving and repositioning the LSR32s is not a trivial task because of their size and weight. However, I quickly discovered that the port on the front and the recessed terminal panel on the rear provided excellent finger‑grips for lifting the cabinet. Whether by design or accident I know not, but the balance of the cabinet and the positioning of the grip points are almost ideal for the purpose!

The cabinet is a conventional rectangular MDF box finished in a matt black 'sand‑texture'. It incorporates some internal bracing and a small amount of glass‑fibre wadding on all side and rear surfaces. The crossover is mounted behind the woofer on the rear panel and good quality components and wiring are used throughout. An unusual aspect of the design is that the front baffle is made of carbon fibre 38mm thick. This is claimed to be virtually resonance‑free, and has radiused edges to minimise sound diffraction from the discontinuities of the cabinet sides. There is no provision for a front grille, nor any protection for the drivers, although they are all recessed to some degree and should not suffer accidental damage in normal use.

The LSRs are handed — they are supplied as pairs with the tweeters and midrange units on opposite sides. The packing cases denote the speakers as LSR32L and LSR32R, implying that the drive units should be on the outside edges when set up for stereo listening, but the speakers themselves do not appear to carry any designations at all. Nor does the brochure supplied with each speaker provide any advice on recommended siting (relative to rear wall or ideal listening axis for example). Surprisingly, the review pair did not even have consecutive or related serial numbers. However, they certainly worked very well as a stereo pair, which is presumably a good indication of the consistency of the production line.

The tweeter, midrange driver and port are all mounted on a square cast‑aluminium sub‑baffle which can be removed and rotated to allow the speakers to be mounted vertically or horizontally, whilst maintaining the vertical alignment of midrange and tweeter (for accurate stereo imaging) and the correct dispersion angles for the off‑axis energy distribution. Apparently, the response of the system remains almost identical with horizontal or vertical cabinet configurations.

As delivered, the speakers were configured for horizontal use, but eight minutes and 16 crosshead screws had them realigned for my preferred vertical arrangement, and placed on a pair of very sturdy stands. I positioned the LSRs with their fronts about 18 inches from the rear wall, and toed‑in to cross axes slightly in front of the listening position. Although I experimented with positioning once I had become familiar with the speakers, I found this starting point to be the best arrangement in my listening room.

Drivers And Crossovers

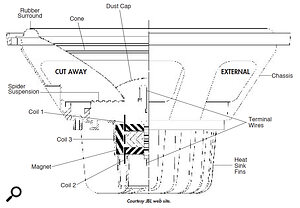

The LSR32 boasts three 'advanced' drivers. The 252G 12‑inch woofer employs a carbon fibre and polypropylene composite cone, supported on the outer edge by a soft butyl rubber roll surround. The motor assembly is based on JBL's patented DCD technology which is very unusual in its use of three voice coils — the two outer ones provide the motive force, whilst the central coil is shorted (its terminals connected together) and acts as a dynamic brake limiting the maximum cone excursion to protect the driver without adding to the distortion at high sound levels.

Most loudspeaker designers follow the theory that linearity stems from ensuring the voice coil remains within a uniform magnetic flux — hence the prevalence of the short voice coil in a long magnetic gap. JBL have instead followed a radical path whereby each of the two voice coils are deliberately arranged to start off half way out of the magnetic gap. The flux from the neodymium magnet is arranged to pass in opposite directions through the two coils (looking at the cutaway diagram of the drive unit, above, the magnetic field effectively flows clockwise, left to right through coil 1 and right to left through coil 2), but as the coils are wired in opposite polarities, their mechanical efforts add to move the speaker cone as required.

Although apparently complicated, JBL claim a number of advantages to this novel approach for a given specification of electrical‑to‑mechanical coupling. Since there is double the surface area of coil, the heat dissipation is far better allowing a 3dB increase in power handling and a reduction in dynamic compression. As the two coils are wound in opposite phases, their mutual inductance is reduced helping to provide a flatter impedance curve to the amplifier, again making the loudspeaker easier to drive. Also, the entire magnet and voice coil assembly can be made more compact and requires less iron in the magnetic path than most designs, making it lighter. These combine to allow greater efficiency in heat dissipation and improved power handling.

The central, shorted coil does nothing at all most of the time, as it is well away from the two magnetic gaps. However, during high cone excursions, the third coil enters the magnetic field and a current is induced within it. This sets up an opposing magnetic force which acts against the motion of the cone, thus damping the movement and acting as a brake. The design is certainly clever, and apparently the introduction of the third coil into the magnetic gap helps to cancel the inherent distortion artefacts caused by the magnetic field instability as the main voice coils reach the outer edges!

The C500G midrange driver is a more conventional design with a two‑inch kevlar cone, again supported on a butyl rubber surround. The voice coil has the same diameter as the cone and works with a neodymium magnet for high power handling. The unit is housed in a cylindrical metal chamber and is designed to cover a frequency range of 250Hz to 2.2kHz. The 053ti tweeter employs a one‑inch titanium dome damped with a substance called Aquaplas as well as a "unique low recovery foam" in the rear chamber. This high‑frequency driver is mounted to the baffle via an 'Elliptical Oblate Spheroidal Waveguide' (fortunately abbreviated to EOS!), which controls the horizontal and vertical dispersion characteristics of the tweeter to 100x60 degrees respectively. The tweeter is intended to cover the range from 2.2kHz to well over 20kHz.

The crossover network presents a nominal load of 4Ω and allows bi‑wiring via two pairs of '5‑way' 4mm/binding posts on the rear panel. As supplied, metal links short the high and low sections together, but these are easily removed if required. I auditioned the LSR32s in bi‑wired mode simply because my normal monitors (PMC AB1s) are also configured for bi‑wiring (I once managed to convince myself that I could hear an improvement with a ludicrously expensive bi‑wired cable...).

The crossover employs fourth‑order (24dB/octave) Linkwitz‑Riley filters claimed to minimise lobing at the crossover points. Lobing is an inherent but detrimental side effect of dividing the frequency range between multiple drivers, and can have an adverse affect on the off‑axis energy balance from the speaker. The crossovers incorporate both magnitude and phase correction at the crossover points, and a very mild ‑1dB level trim option is available for the tweeter if required via links on the rear panel. Decent‑quality crossover components are arranged carefully on a large circuit board mounted on the inside of the cabinet's rear panel and linked with respectably chunky wire to the drivers. JBL's published plots of the system impedance and phase are commendably controlled and my amplifier had no problem driving the LSRs at all.

Listening

I must admit I approached auditioning the LSRs with a certain amount of trepidation. I was never a fan of the 'JBL sound', which I always felt was brash, coloured, typically American (I don't mean to be nationalist, but American speakers have always sounded different to British ones), and fatiguing. Not the qualities which make a decent monitor speaker, in my opinion!

So imagine my surprise when I first heard these speakers last year at the New York AES Convention. It has taken a long time to get hold of a pair for a proper review in decent listening conditions, but I am even more impressed now than I was then. These speakers have changed my views of JBL for ever. I cannot stress too highly what a high grade product the LSR32 is, and there are a lot of British manufacturers around in this sector of the market who now have some very serious competition to deal with.

...there are a lot of British manufacturers around in this sector of the market who now have some very serious competition to deal with.

These loudspeakers are impressive. They can sound smooth, delicate, revealing, clear, neutral and uncoloured, but are also weighty and dynamic when the music calls for it (but not in an over‑the‑top way). They can generate frightening sound pressure levels with very little hardening of the sound quality, and could probably cope with ear‑splitting abuse all day if necessary, such is the build quality and solid engineering of the drive units.

Although it is clear from first auditioning that the LSR employs a metal (titanium) tweeter, it does not exhibit that typically metallic ringy quality that gave such devices a bad name in the '80s. It actually sounds very smooth and controlled with an excellent balance of revealing inner details without becoming fatiguing, even after long periods.

The midrange driver deserves praise too for its ability to present complex audio signals with fine clarity. A well‑designed three‑way system will always outperform a good two‑way, simply because of the extra driver to handle the inevitably complex midrange portion of the audio signal. The LSR demonstrates this very well when compared to my (two‑way) PMC AB1s which, although extremely good and certainly worthy of the monitor quality label, were clearly outperformed by the LSRs in midrange detail.

This was made very obvious when I auditioned a couple of tracks from Chesky Records' The Ultimate Demonstration Disc which is full of very challenging music. In an excerpt from Vivaldi's Flute Concerto in D (a rather busy piece of music) the starts of the flute phrases are often obscured by the rest of the instrumentation on average speakers. A decent monitor should be able to separate out the various instruments playing at the time and my PMCs can just about manage that, but the JBLs presented the flute very clearly as a distinct and separate instrument with its own audio environment perfectly intact, and the other instruments all just as clearly defined.

This example also raises another point. The idea of listening to 'serious music' on JBLs would once have had many engineers running for their earplugs, but the LSRs are quite at home with all types of music and voice — the sign of a truly well‑balanced monitor loudspeaker system.

Stereo imaging and focus were to very high standards, and once I had the LSRs sufficiently toed‑in, a good wide 'sweet‑spot' could be created with natural and stable spatial presentations. Depth information was also conveyed well. Bass extension is good, as one might expect from a 12‑inch driver, although careful room placement is important of course. Certainly, there was plenty of energy around to stimulate involuntary foot‑tapping (another good sign of a well balanced speaker), and bass instruments and drums were expressed with the solidity and weight required (whether for natural acoustic music or driving synth lines and heavily processed drum kits).

With the speech tests from the useful Canford Audio Quick Check CD, the excellence of the midrange was clear in its resolution and neutrality. The accurate matching of the drivers and crossover was also revealed by moving around in front and to the sides of the speaker: the sound quality remained remarkably consistent without abrupt changes, demonstrating how well the off‑axis output has been controlled.

I didn't expect these JBL LSR32s to sound as good as they do, and I tried everything I could to reveal weaknesses in their presentation. However, with each new challenge I became more and more impressed. Sure, there are better monitors available, but not many at this price point. The LSRs compete in the same ball park as the Genelec 1031A, Harbeth Monitor 30, Dynaudio BM15A, ATC SCM20SL Pro, PMC IB1S, and Tannoy 1200DMTII to name but a few respectable monitors. At the price, I would rate the LSR32s as a bit of a bargain, and if you have the space, the requirement and the budget, the LSR32s should definitely be on your auditioning list.

Figures, Plots And Specs

The LSR32s are very highly specified. Their quoted sensitivity is 90dB/W at 1m which is about average, with an anechoic frequency response between the limits of +1/‑1.5dB from 60Hz to 22kHz. In fact the bottom end is significantly extended on this in typical in‑room conditions with substantial energy being output to below 35Hz (the enclosure resonance is tuned to 33Hz). The recommended minimum amplifier power is 150W into 4Ω (with a maximum of 1000W) but I would suggest 250W is a more sensible figure for the headroom required in typical control room monitoring. I used a Bryston 4B amplifier which seemed very well suited to extracting near real‑life dynamics from the LSRs when required (the 4B is rated at 400W into 4Ω).

The distortion figures for the LSR32 are impressively low, with under 0.5 percent for second and third harmonic above 120Hz at a highish listening level of 96dB SPL (rising slightly to around 1 percent at 102dB SPL). Below 120Hz, the second‑ and third‑harmonic distortion figures are better than 1.5 and 1 percent respectively at all power levels, presumably thanks to the DCD motor design of the LF driver. Power compression is also well controlled at under 1dB for 100W input, and JBL show a pretty tidy impulse response for the system on the brochure with all most of the HF ringing tamed within 0.5mS and the LF ringing all done within 1mS. This confirms the smooth and well controlled phase response of the crossover.

Pros

- Professional and robust build quality.

- Able to cope with most forms of abuse.

- Accurate, neutral and detailed sound.

- Wide and consistent listening area with stable imaging.

- Very competitive pricing.

Cons

- Passive.

- That JBL badge might stir up preconceptions.

- Midfield design means room acoustics can be influential on sound quality.

- They wanted them back..

Summary

The result of a rethink in the design department, JBL's LSR32s are a passive three‑way design with excellent resolution, a wide and consistent listening area, and stable imaging. They have JBL's usual robust construction and power handling, but also offer a delicate, detailed and neutral sound. The LSR32s are JBL monitors of which the most demanding audiophile would approve.