These 1950s compressors are probably the most revered — and imitated — processors in the world. But what is it that makes them so special?

The Fairchild 660/670 compressor-limiter is arguably the most iconic of all dynamics processors. A decent plug-in emulation can now be considered pretty much a standard tool, and there are quite a few to choose from. There are also, in current production, quite a few hardware units that are inspired in some way by these legendary limiters, and a few manufacturers even offer precise clones of the original circuitry. But why? Just what is it that has bestowed such an enviable reputation on this legendary processor?

In common with other ‘legends’, it’s fair to say that a number of factors are responsible for the Fairchild’s enviable status, and as with all legends, the truth becomes a little distorted. Its age certainly plays a role; its decades of deployment in control rooms across the globe, and on such a range of commercial material, have contributed to its mystique. Its relative scarcity has also made it an expensive collector’s item and, despite all the maintenance issues, the asking price for vintage specimens keeps rising (at the time of writing, originals are fetching prices upwards of £20,000).

But there are plenty of rare old processors which lack the Fairchild’s fame and desirability. In short, despite its age and scarcity, this behemoth limiter would not be so desirable if we didn’t also love its special sound character. A well-maintained Fairchild sounds fantastic, even by modern standards, and if you know how to use it — or one of its many software or hardware imitators — it remains a very useful and great-sounding studio tool today.

The aim of this article is to separate the fact from the fiction, which I’ll do by taking a closer look at the Fairchild’s origins, explaining some technical details and describing the typical sonic attributes of this most classic of processors. Perhaps we’ll bust a myth or two along the way...

Origins

The original Fairchild was developed in the early ‘50s by Rein Narma, an American engineer with Estonian roots. Earlier in his career, Narma had constructed mixing consoles for the likes of Rudy Van Gelder and Les Paul, and history has it that the latter, the famous guitarist and inventor, may have provided the impetus to design the compressor. One way or another, the work was finally carried out under the roof of the Fairchild Equipment Corporation, with Narma as the lead engineer overseeing the project.

Fairchild offered both a mono version, the 660 (shown here), and the dual-channel 670.

Fairchild offered both a mono version, the 660 (shown here), and the dual-channel 670.

All of the design characteristics of the Fairchild were conceived for maximum level control and minimum artifacts — its development took place in an era when pretty much all engineers tried their best to record sources as naturally and pristine-sounding as was possible. Compressors and equalisers were almost universally viewed as tools to help an engineer achieve the clearest, most natural-sounding results, rather than as the ‘colour’ processors or ‘groove tools’ that are in vogue today. They were typically deployed for fairly mundane tasks: radio transmitter valves and cutting styli could be damaged by unwanted high levels, and dynamic tools like the Fairchild were used to keep those dangerous peaks in check, thus helping to maintain a healthy programme level for the following devices in the signal chain.

Furthermore, the Fairchild was designed at a time when stereophonic recording techniques and the stereo vinyl record were becoming established. Virtually twice the amount of information as on a mono LP needed to be stored on the same size surface for a stereo record. To maintain parameters like programme length and level, dynamic shaping of the audio material was essential. The Mid-Sides (M-S) process helped to save lacquer real estate during the cutting process, and (an equally important benefit at the time) it retained mono compatibility. It was for this very reason the two-channel Fairchild 670 was designed for use either as a dual-mono unit (with unlinked stereo channels) or in M-S mode. (The mono 660 version and the dual-channel 670 were released almost at the same time.)

Yet the Fairchild was not only conceived as a protective device in front of a cutting lathe. It was also advertised — and used — as a broadcast limiter. Around 1000 stereo units were sold in the early years, and while that might not sound impressive today, numbers like that meant it was a huge success at the time: it wasn’t until the late ‘50s that independent recording studios and broadcast houses began to emerge, and subsequently there was much less demand for professional audio devices at that time than today. A magazine ad praised the Fairchild as the “World Accepted Standard For Level Control” at the time, and the description was spot-on. There may have been plenty of alternatives available — including but by no means not limited to the Gates Sta-Level — but the Fairchild was a huge success indeed.

Relatively quickly, though, as recording techniques evolved through the 1960s, engineers began to discover the more creative tone-shaping capabilities of the Fairchild. It’s well documented how several Fairchild 660 units became key weapons in Abbey Road’s arsenal. Those units were used on virtually all Beatles recordings after their introduction at the London studios. Since the A Hard Day’s Night sessions in 1964, almost all the Beatles’ vocals were sent through the Fairchilds, and the American limiters also played a huge role in shaping the sound of Ringo’s drums, the guitars, and many more sources. The Beatles pedigree greatly helped to establish the Fairchild as a classic choice in music-production facilities all over the world.

Tech Talk

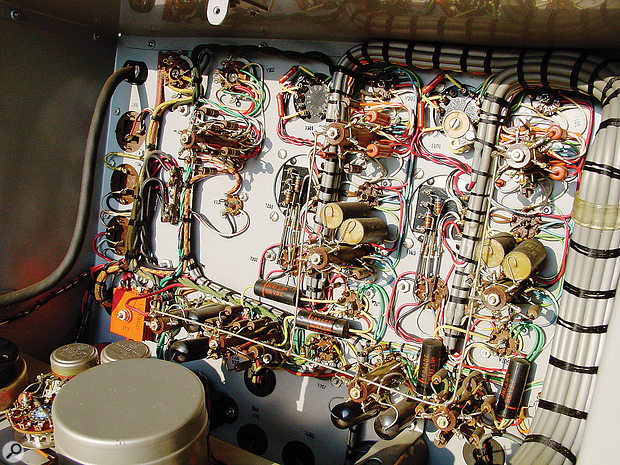

Transparent peak limiting and a sound as natural and pristine as possible... That reads like a not-too spectacular goal these days, but it required a complex hardware design half a century ago. The Fairchild employs no fewer than 20 valves with 30 systems and 11 transformers. Its solid 6U enclosure weighs in at a hefty 30kg. Most of the numerous parts and pieces in the circuitry aren’t employed in the signal path, which, as is typical of designs from this era, is simple: the input transformer is followed by a single, variable push/pull valve stage, and the signal is then fed directly to the output transformer. The rest of the components help to shape the processor’s side-chain control voltage.

As simple as the signal flow may appear at first glance, closer inspection reveals the circuit to be more sophisticated. In the central valve stage, which combines both gain-cell and output-amplification duties, each channel employs no fewer than four 6386 dual-triode valves. This, in turn, means that each half of the push/pull stage relies on four triode elements wired in parallel. This amplification circuitry behaves like a single gain stage, albeit one with a very low impedance. Combined with the (even for valve circuitry) extremely high control voltages, this trick minimises undesirable artifacts like noise and signal distortion.

Impressive circuitry: the 670 boasts no fewer than 20 valves and 11 transformers.

Impressive circuitry: the 670 boasts no fewer than 20 valves and 11 transformers.

Such a complex setup requires precise calibration. The user manual suggests a warm up period of 30 minutes, which is a long time even by valve-equipment standards. This valve setup is the reason maintaining and servicing a Fairchild has never been easy — and why it is becoming more and more difficult to keep a vintage unit in a good, stable working condition. The Fairchild is said to ‘eat’ the 6386 valves at a fast pace. The original 6386 was phased out a long time ago, and NOS types are becoming scarce, fetching premium prices. A modern equivalent is available from JJ Electronic, but the debate over whether this new valve is a worthy successor to tried and true NOS specimens hasn’t yet been settled!

Setting aside the parallel wiring of multiple valve stages, the otherwise basic layout of the circuitry is typical for the era in which the Fairchild was born, and the same can be said for the simple set of controls. A rotary switch increases the input signal in 1dB steps, and there’s a rotary threshold control. Switches select L-R or M-S operation on the Fairchild 670, and the VU meter mode, which can display gain reduction or plate current, for calibration purposes. There’s also a single switch offering six time-constant ‘presets’ — in other words, each switch position selects a different pairing of attack and release times (see box). All positions offer extremely fast attack values, between 0.2 and 0.8 milliseconds. This was considered to be lightning fast at the time, and the figures weren’t beaten until a decade later, when solid-state units with FET gain cells (like the Universal Audio 1176LN) brought attack values down to a mere 20 microseconds. Given its primary purpose as a protective device in broadcast or vinyl cutting environments, in which the limiter was required to catch any unwanted signal peaks reliably, these fast attack times were one of the Fairchild’s most important features.

A happy by-product of this objective was soon discovered, though: the Fairchild didn’t only manage to keep those nasty transients in check on full programme material, but also proved an excellent cure for sibilance and harsh, spitty vocal consonants. Granted, a number of other factors contributed to the final result, but the buttery, smooth vocal sound of the Beatles can be attributed in no small part to the creamy compression of the Fairchild.

The fastest available release setting of 300 milliseconds is an acceptable value even today. As an interesting side note, the two fastest time-constant settings (see box) were recommended for pop productions, and the following two presets for classical music. In addition, the Fairchild also boasts two settings with a programme-adaptive release curve, and the last setting is particularly interesting. It offers, depending on peak level and intensity, a release of 300 milliseconds for signal peaks and up to 25 seconds for average level. Interestingly, nowadays most engineers seem to favour the fastest setting, and on most Fairchilds still in service today, the time-constant switch can usually be seen set to the ‘1’ position.

Fine details aside, no matter how you look at it, this compressor generally combines fairly fast attack times with a fairly long release. This behaviour was important, because it guaranteed reliable peak control and a natural-sounding release with minimum unwanted artifacts like ‘pumping’ — all of which made it perfect for inaudible level control during broadcast or cutting. It’s this characteristic which largely defines the distinct personality of the Fairchild today.

Further typical attributes of the Fairchild sound are the feedback design of the circuitry and the compression ‘curve’. As with most vintage dynamic processors, the side-chain signal is tapped after the gain cell, something which helps to stabilise the circuit, evens out unruly behaviour and also adds to the programme-dependent nature of the compression. An inherent feature of the variable-mu compression principle is the soft knee of the compression curve. Gain reduction starts with a very low ratio, between 1:1 and 2:1 for smaller peaks, and gradually increases to a ratio of up to 20:1 on loud input signals. On the Fairchild, the curve can be adjusted to some degree by way of an internal trim pot. It allows for a broad range from a very smooth transition between compression and harder limiting, to a more pronounced, harder knee.

A peek inside reveals the point-to-point wiring.

A peek inside reveals the point-to-point wiring.

Modern Applications

As I’ve explained, the Fairchild’s compression character is largely defined by its short attack and long release times, and this means it’s destined for applications where you wish for fairly unobtrusive gain riding, yet with a solid grip on the transients. You should not expect this compressor to pump and breathe like, for example, an 1176 — such aggressive ‘effect’ compression requires release values that are way below the Fairchild’s minimum of 300 milliseconds!

Its fastest time-constant setting (‘1’) seems to be laid out perfectly for use on vocal channels and vocal buses — in fact, it’s on such sources that the Fairchild can sound particularly glorious.

Although the Fairchild, especially the 670 stereo version, has its origins in bus and programme processing —and may have done a stellar job back in the day — the overall frequency range and desired pressure levels of popular music have advanced since the ‘50s and ‘60s; the loud, fat and aggressive bass levels that have become common (in many genres, not just urban and club music) weren’t even on the horizon when the Fairchild was designed. Thus, great care should be taken when deploying a Fairchild (or one of its hardware or plug-in adaptations) in these roles today.

For thick, broad bass transients to come through bus-compression unscathed, or to be made even more pronounced, a bus compressor must offer long-ish attack times. Typically, for mix-bus compression, the attack parameter has to be set somewhere between 10 and 120 milliseconds; an attack time in the microseconds range will prove way too short, and suck all the punch and life out of the programme. At the other extreme, when it comes to straight-forward limiting, digital processors employing a lookahead function have more than a slight edge over their analogue forbears.

This, I suppose, is the most common misconception about the Fairchild from today’s perspective — the idea that because it was an ideal ‘quasi brickwall’ limiter in its day, it should make an ideal mix-bus compressor today. Granted, if it sounds right, it probably is right, and I don’t mean to discourage you from trying out a Fairchild-type limiter on the mix bus. It may even work very well in a given situation, but especially when handling large amounts of punchy bass the Fairchild is far away from being a good bet as a mix-bus compressor when working with a lot of modern material.

But even though the Fairchild might not be the perfect solution for contemporary mix and drum buses, it’s capable of doing a wonderful job on other mix groups such as a horn, keyboard or vocal bus. Few other compressors can provide a similar quality of ‘glue’ to a combined bus signal. The Fairchild can seemingly weld signals together; the output very often sounds somehow like one, cohesive ‘block’ of audio, without much gain reduction registering on the meter. The key factors are the mutual envelope shaping, due to the rather fast attack parameter, and also, of course, the sound of the compressor’s line stages. The Fairchild actually offers quite subtle signal colouration, but it yields results that can be hard to achieve by alternative means. Very often, a signal that has been fed through this valve and transformer behemoth sounds more focussed and more contoured; it gains a tangible, three-dimensional aesthetic.

By the way, one other factor probably contributed to the Fairchild’s reputation: not only has it always enjoyed a reputation for sounding good, but it is also fun to use — and it has always been this way. In fact, the legendary limiter provided the inspiration for some downright funny effects. The wobbly background vocals of the Beatles’ ‘Octopus’s Garden’, for instance, were achieved by way of compressing them with a Fairchild 660, whose side-chain was fed with a pulsing LFO.

Alternatives Abound

Whether these elusive, elegant capabilities can be achieved with modern Fairchild inspired plug-ins — or, more precisely, whether they can emulate all the subtleties of the original high-voltage valve stages and the rather special transformers — is still open to debate. But it should go without saying that the latest generation of plug-in offerings by vendors such as Universal Audio, Waves and Acustica Audio gets us more than just in the ballpark. And for hardware aficionados there is ample supply today, despite the scarcity of coveted vintage originals. Many vari-mu compressors, such as the Pendulum ES-8, are at least to some degree inspired by the Fairchild, and some units can even be custom-ordered with original NOS 6386 valves, even though the regular version relies on other types of remote cutoff valves. Boutique manufacturers, including ADL, Analoguetube, Pom Audio and UnderTone Audio, strive to offer units that are way more authentic than just ‘Fairchild-inspired’, but of course these compressors not only rival the original in parameters like size and weight, they often fetch premium prices, too. And then there are also companies like Amtec Audio, who emulate the Fairchild concept but with a simpler valve layout, thus helping to minimise production efforts and costs. The Amtec 099 is a good example of such a ‘modern’ Fairchild — it offers many of the sonic attributes of the original, yet it comes in a smaller, more affordable form, and it still adds a few additional parameters to the archetypal feature set. And the modern 6368 valve remake by JJ adds more options to this field, as good-sounding NOS types are getting scarce. In short, if you’re planning to infuse your productions with some classic Fairchild goodness, the options to suit most pockets are plentiful.

Time-constant Settings

|

Switch Position |

Attack (ms) |

Release (sec) |

|

1 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

|

2 |

0.2 |

0.8 |

|

3 |

0.4 |

2 |

|

4 |

0.8 |

5 |

|

5 |

0.4 |

2 (peaks), 10 (multiple peaks) |

|

6 |

0.2 |

0.3 (peaks), 10 (multiple peaks), 25 (programme material) |