Is Apple’s Mac Studio the perfect computer for the studio?

Apple users with long memories will remember the stunning, fanless PowerMac G4 Cube. Launched back in 2000, the Cube ended up being too limited for professionals and too expensive for other users, and was discontinued after just one year. However, Apple persisted with the idea of a miniature desktop machine, and four years later, the Mac Mini saw the light of day. It’s been a great success, and is widely used in music studios, but is there still room for a more pro‑oriented compact machine? Apple obviously think so, and the result is the Mac Studio.

Hip To Be Square

The Studio and Mini both occupy the same 7.7‑inch square (197mm) footprint, but at 3.7 inches (95mm), the Studio is nearly three times as tall (it fits comfortably within 3U of rack space). It’s also somewhat heavier. The Mac Mini weighs in at 2.6lb (1.2kg), while the Studio is 5.9 or 7.9 lb (2.7 or 3.6 kg), depending on how it’s configured.

To cool the inside of the system, Apple’s engineers have once again created a unique and innovative thermal architecture, parts of which are visible from the outside. Using a double‑sided blower (more commonly found in fireplaces), air is pulled in through the perforated circumference around the base of the enclosure and guided over the circular power supply to the chip’s thermal module. The warm air is then pushed out the back of the machine, through over 2000 precisely machined perforations, by a low‑impedance rear exhaust.

The Mac Studio’s cooling system pulls air into and across the system from the bottom of the enclosure, before pushing it out of the rear exhaust.

The Mac Studio’s cooling system pulls air into and across the system from the bottom of the enclosure, before pushing it out of the rear exhaust.

Given that the M1 series of chips are already designed for energy efficiency, this means the system is barely audible in use. So much so, in fact, that according to tests compliant with the ECMA‑109 standard (for “Declared noise emission values of information technology and telecommunications equipment”), the Mac Studio emits only 15dB SPL as measured from the operator’s position. To put this in context, if you remember those charts you were shown at school, 15dB is between the sound of calm breathing or leaves rustling (10dB) and whispering (25dB).

I don’t recall ever hearing any audibly obtrusive fan noise during the test period, even though the Mac Studio was placed on the desk in front of me. It simply didn’t seem interested in pushing any air though the system, whether I was running Geekbench tests or even when trying to play back a complex Pro Tools session. The only time I really got it going was running GFXBench, which throttles all the GPU cores on the chip in a manner that music and audio software does not. Some users have reported issues with persistent fan noise, but this didn’t seem to be a problem with the test machine, and I wouldn’t be afraid to use it in a live room with a musician.

Putting The ‘A’ Back Into USB

Given the physical similarities, it makes sense that Apple would use the Mac Mini’s connectivity as a starting point for that of the Studio, and that is exactly what the company’s engineers have done. On the rear you’ll find four USB‑C connectors supporting Thunderbolt 4 (allowing for speedy data transfer of up to 40Gb/s), DisplayPort (up to 6K resolution), USB 4 (also up to 40Gb/s), USB 3.1 Gen 2 (up to 10Gb/s), and a maximum of 15W for supplying power to bus‑powered devices. Joining the USB‑C ports are two USB‑A connectors supporting up to 5Gb/s for MIDI interfaces, dongles, other input peripherals and anything else you might need it for.

Rear panel: Good news, folks: ports are back! Even the venerable USB Type A port, long since considered an endangered species.

Rear panel: Good news, folks: ports are back! Even the venerable USB Type A port, long since considered an endangered species.

With the combination of ports and the graphics processing capabilities of the M1 Max or Ultra chip, it’s possible to connect a maximum of five external displays to the Mac Studio, pushing nearly 90 million pixels! Each of the four Thunderbolt 4 ports can be used to drive a display with a maximum 6K resolution, such as Apple’s own Pro Display XDR, and there’s also an HDMI port (as on the Mini and the 2021 MacBook Pro models) that supports an additional 4K display. This is useful if you want to use a separate display, like a TV, to show picture if you’re working on a project with video assets.

The Mac Pro offers dual‑10Gb Ethernet networking, and it would have been nice if this had carried through to the Mac Studio, but there’s just the one 10Gb Ethernet port as standard. It also features the same wireless networking capabilities as the MacBook Pro, with support for Wi‑Fi 6 (technically known as 802.11ax, which is compatible with the earlier 802.11a/b/g/n/ac standards) and Bluetooth 5.

Completing our tour of the Mac Studio’s rear is the 3.5mm audio jack for attaching headphones or active speakers. As with the most recent MacBook Pro models, this audio output supports both high‑impedance headphones and a true line output.

Apple Inside

When Apple launched the new 14‑ and 16‑inch MacBook Pro models near the end of 2021, it was revealed — after much speculation — they were to be powered by two new members of the M1 SoC family: the M1 Pro and the M1 Max chips.

The M1 Pro was a natural evolution from the original M1 chip Apple launched the year before. Where the M1 had an eight‑core CPU comprising four performance and four energy cores, the M1 Pro builds on the M1’s foundations to offer either an 8‑ or 10‑core CPU (of which two are efficiency cores). And, perhaps even more impressively, the M1 Pro doubled the numbers associated with the GPU and Unified Memory. The number of GPU cores went from seven or eight to 14 or 16 cores, while the largest amount of Unified Memory went from 8 or 16 GB to 16 or 32 GB with 200GB/s bandwidth.

In addition to the quantitative CPU, GPU and Unified Memory improvements, the M1 Pro also introduced the so‑called Media Engine to do for video encoding and decoding what the Neural Engine had done for machine learning. The Media Engine is built on the M1’s image signal processing and media encode/decode engines, adding capabilities that were previously only available to Mac Pro users with an Afterburner card. It provides hardware acceleration for H.264, HEVC (H.265), ProRes, and ProRes RAW video codecs, using a video decoding engine, a video encoding engine, and a dedicated decode and encode engine for handling ProRes.

An insider’s perspective. This X‑ray view of the Mac Studio shows off the elegant internal engineering performed by Apple’s engineers.

An insider’s perspective. This X‑ray view of the Mac Studio shows off the elegant internal engineering performed by Apple’s engineers.

The M1 Max represented another giant leap, embracing the M1 Pro’s more powerful architecture to once again increase the number of GPU cores to 24 or 32, and doubling both the memory bandwidth and the capacities of Unified Memory available, to a rate of 400GB/s and amounts of either 32 or 64 GB respectively. The Media Engine was also boosted with the addition of an extra video decoding engine, and another ProRes decode and encode engine.

The reason for recapping some of these chip specifications from the MacBook Pro is because the M1 Max chip is used as standard for the base Mac Studio model, with 32GB Unified Memory and a 24‑core GPU. Spend more and you can get an M1 Max with either 64GB Unified Memory, a 32‑core GPU, or both. And should you want yet more performance, Apple also took the opportunity to unveil what was described as the last member of the M1 family, the M1 Ultra, which can be ordered with higher‑end Mac Studio configurations.

The M1 Ultra basically offers twice the capabilities of the M1 Max by literally putting two M1 Max chips together in the M1 Ultra’s packaging with the memory...

The M1 Ultra basically offers twice the capabilities of the M1 Max by literally putting two M1 Max chips together in the M1 Ultra’s packaging with the memory, making use of a hitherto unannounced feature of the M1 Max that Apple have decided to name UltraFusion. This is a new interconnect technology that acts as the glue to make two M1 Max systems appear as a single system to the computer, while preserving the benefits of Unified Memory.

In many ways, this approach is analogous to the days when high‑end desktops — such as certain models of Apple’s own PowerMac G5 and the first Mac Pro — borrowed from the server world to put more than one processor on the computer’s motherboard. However, rather than putting two M1 Max chips on a motherboard, which would have increased the latency between them and forced software developers to write specific code to take advantage of such a system, Apple instead chose to put all the silicon in a single package. UltraFusion offers so much bandwidth that the amount of latency falls well below where it would ever cause a problem in allowing two M1 Max chips to act as one. We were not able to test an M1 Ultra machine for this review, sadly.

On The Bench

To evaluate the performance that’s achievable from these machines, I began with Primate Labs’ Geekbench to see how the M1 Max‑based Mac Studio compared with similar machines and chips I’ve tested. Running the CPU Benchmark for Apple Silicon, the Mac Studio with M1 Max achieved single‑ and multi‑core scores of 1769 and 12433 respectively.

This chart shows the Geekbench scores for several related Macs I’ve tested over the past few years, except for the Mac Studio with an M1 Ultra where the score is taken from the Geekbench Browser.

This chart shows the Geekbench scores for several related Macs I’ve tested over the past few years, except for the Mac Studio with an M1 Ultra where the score is taken from the Geekbench Browser.

As you can see from the chart, the Mac Studio with M1 Max performs in the same ballpark as my 14‑ and 16‑inch MacBook Pros with M1 Pro and M1 Max processors, and what’s particularly interesting is that an ARM‑based CPU core performs roughly the same across all M1‑based silicon. You can also see that the M1 Pro and Max‑based Macs nudge just ahead of the performance you’d get from an older iMac Pro or a newer 27‑inch iMac. And the Mac Studio with the M1 Ultra performs satisfyingly better than the current 24‑core Mac Pro. The biggest difference between these two systems? Oh, about $8000£7500!

Obviously, as these results indicate, performance for an M1‑native application is more than satisfactory, but how does the Mac Studio perform for those of us (most of us?) who are still using non‑M1 software? Fortunately, I had to do an Atmos mix in Pro Tools while I was writing this review, which provided an excellent opportunity for testing. I loaded up the Mac Studio with the requisite software: Pro Tools Ultimate (with Carbon), the Dolby Atmos Renderer with its Core Audio driver, and the usual truckload of plug‑ins from iZotope, Nugen, Sonnox, Sound Particles, Soundtoys and so on. Everything went swimmingly well, and it was only after a few days I remembered that all these ones and zeroes were intended for Intel‑based Macs and were running here with the aid of Rosetta 2! So far so ARM.

However, quantifying how much performance the Studio can bring to your studio (as with any computer) is a difficult task, especially since numbers of tracks and plug‑ins don’t really tell you all that much. Factor in that the days of mono and stereo channels are over, and the performance metering in most music and audio software is woefully inadequate — a subject for another day — and you have the perfect recipe for a migraine.

To put the Mac Studio through its paces, I wanted to use a real‑world session that anyone could download for comparison. Netflix conveniently host a selection of what the company term as ‘Open Content’ available for download, with the goal of providing “a common reference for prototyping bleeding‑edge technologies within entertainment, technology and academic circles without compromising the security of our original and licensed programming”.

Of these open content titles, Sol Levante includes two example Pro Tools Sessions, representing an excerpt from the final mix and the finished master. So, if you want to follow along, download the Final Mix session from opencontent.netflix.com, which is compressed into an 11.4GB zip file. You’ll need to be running Pro Tools Ultimate on a Mac with the Dolby Atmos Renderer; trial versions of all the software required are available, including Avid’s Pro Limiter, Multiband Dynamics and Subharmonic plug‑ins, along with ReVibe II.

To put what I was trying to play back in perspective, in terms of plug‑ins, the session contains 199 instances of Channel Strip, plus 49, 42 and four instances of Pro Limiter, Pro Multiband Dynamics and Pro Subharmonic respectively, not forgetting 23 instances of ReVibe II. That makes for a total 317 inserts; and, if that doesn’t sound like all that many, consider this is over a mixture of mono, stereo, quad, 5.0, 7.1 and 10.1.2 channel configurations. So the total number of mono streams being processed by the aforementioned plug‑ins is 638! (Along with many unprocessed streams I didn’t include.) And all of this was running natively, as I was routing 93 outputs via the Dolby Bridge virtual audio device to the Dolby Atmos Renderer on the same system as Pro Tools.

When I began playback, Pro Tools initially gave me the dreaded AAE ‑9173 error: “Pro Tools ran out of CPU power.” I tried enabling the disk cache so that all the audio data was preloaded into memory, but as was predictable: still no joy. Therefore, I began removing — in a not particularly scientific manner — the inserts used by tracks within seven of the Folders. This left 283 mono streams of processing, with 151 instances of Channel Strip and 26 instances of Pro Multiband Dynamics. After this, the Session played back fine with approximately 77 percent usage, as reported by Pro Tools’ slightly dubious CPU Total meter in the System Usage window.

Mac Vs Mac

For comparison, I decided to see how the Mac Studio compared to the last Intel‑based iMac Apple shipped, which was discontinued on the same day as the Mac Studio was announced. The iMac had the same 64GB memory (but obviously not in a Unified configuration) with a 3.6GHz 10‑core Intel Core i9 processor, with AMD Radeon Pro 5700 XT graphics with 16GB of GDDR6 memory. This played back the complete session fine, with Pro Tools reporting around 58 percent CPU usage, while the less demanding session with fewer inserts averaged about 15 percent.

Of course, the big caveat to this outcome is that at the time of writing, an Apple Silicon‑native version of Pro Tools wasn’t available, so the Mac Studio would be starting with quite a high handicap if this was a game of golf. However, there are a few points to consider. Firstly, a cursory look at the numbers would indicate that Rosetta 2 is placing a greater burden on the system than the load observed with equivalent software. This would indicate that, due to the way Pro Tools’ native audio engine distributes itself across cores (and whether or not it usefully differentiates between performance and efficiency cores), the session might still have problems even if an Apple Silicon‑native version of Pro Tools was available.

As a footnote, somebody I know from spending time at a well‑known audio post‑production facility in Marin County, California, did have access to a Mac Studio with an M1 Ultra, and apparently this session played back just fine. However, he also had no problems running it on a 5,1 Mac Pro with 12‑core 2.66GHz Xeon, and the M1 Ultra‑based machine actually reported higher CPU usage. He was using a buffer size of 32 samples on his machines, whereas I was running with a more generous 1024 samples. Therefore, until Avid releases an Apple Silicon‑native version of Pro Tools, we won’t be able to truly know what kind of performance advancement there might be.

M1 Giant Leap?

Whether or not you think Apple cracked the problem of a desktop Mac that sits alongside its three older siblings, it’s hard to contemplate what the company could have done differently to make the Mac Studio warrant a space on the product strategy grid. And perhaps the more important question for anyone reading this review is: should I buy one? Which could be further sharpened with the addition of another word: should I buy one yet?

The answer to this question, as you might expect, very much depends on the software you want or need to run. Although most music and audio applications are now available in native Apple Silicon versions, that’s not to say developers have figured everything out concerning this new hardware platform. Porting a version of an existing application to run natively on Apple Silicon‑based systems, for example, is different than the process of optimising an application to make it perform as well as possible on a new hardware platform. Therefore, you might not observe significant performance gains until developers fully acclimatise and learn some new tricks. Without the availability of a native Apple Silicon version of Pro Tools, the Mac Studio doesn’t yet represent the best option for seriously high‑end Pro Tools users working on demanding projects. However, if your requirements are more modest, and the plug‑ins you need are compatible both with Monterey and Apple Silicon, it might be worth gambling on the future if your current system is in need of replacing.

When you’re running native, optimised Apple Silicon code, the current glass ceiling in performance will shatter and any user working with music or audio in any domain will be able to fully benefit from Apple’s engineering.

On the other hand, if you’re a Logic Pro user, it would be hard not to recommend the Mac Studio! Assuming any third‑party Audio Units plug‑ins are compatible with Monterey, being M1 native is less of an issue since Logic Pro makes it possible to run both x86 and Apple Silicon plug‑ins alongside each other. And, of course, with Apple Silicon‑native applications, it’s easier to gauge the performance differential, even if you simply derive your ratios from the Geekbench scores. Since Steinberg only just released a Universal version of Cubase, it may take a while for issues to become apparent, but my initial impressions are positive, other than the fact you can only use Apple Silicon VST 3 plug‑ins if you run Cubase natively, which is a serious limitation. Performance wise, with ASIO Guard and the improved metrics, it seems very promising.

Right now, with music and audio software, how much power you’ll be able to experience on the higher‑end M1‑series chips like the Max and Ultra will depend on the software you’re running. But when you’re running native, optimised Apple Silicon code, the current glass ceiling in performance will shatter and any user working with music or audio in any domain will be able to fully benefit from Apple’s engineering.

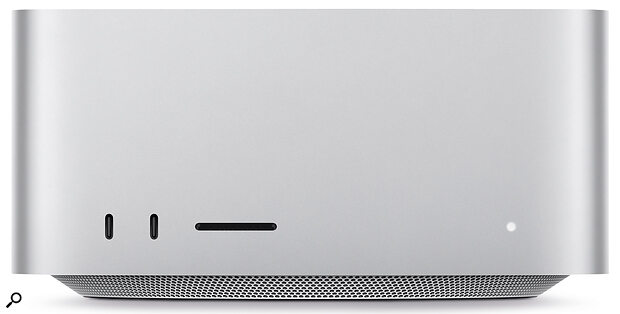

Ports: Front & Slightly To The Left

Where the last two Mac Pro generations in their standing form did away with front‑facing ports, the Mac Studio sees them restored with two USB‑C connectors. One important thing to keep in mind is that Thunderbolt 4 is only supported via these front‑facing USB‑C connectors on the Mac Studio models featuring an M1 Ultra chip. The configurations with an M1 Max chip only deliver USB 3.1 Gen 2 with the usual 10Gb/s speed. Although it would be a shame if this decision was made solely for the sake of price differentiation, it’s possible the M1 Ultra might be needed to support additional Thunderbolt busses since it essentially comprises two M1 Max chips and therefore two Thunderbolt controllers.

The front of the Mac Studio also features a UHS‑II SDXC card slot — what a brilliant idea! — and a power indicator LED. However, what it doesn’t offer is the headphone jack and the power button. Why Apple couldn’t put the headphone jack on the front is, like most things in life, beyond my comprehension — especially since the card slot is finally in a sensible place for a desktop Mac. The Mac Studio’s power button is located to the rear left‑side, and this too could be a real pain in professional environments with machine rooms.

As with the Mac Mini (and the 2013 Mac Pro), Apple have chosen not to include a keyboard or mouse with the Mac Studio, inviting you to either use your own or purchase what you need from Apple. This is probably the right approach, since Apple’s peripherals carry a premium price, and there’s no point paying for bundled extras you might not need or want.

What The GPU?

Here you can see the CPU usage over time whilst playing back one of the Cubase 12 demo songs. The lighter blue graph in the background is the CPU usage with software rendering in Cubase, where the darker blue graph in the foreground is the CPU usage if the rendering is offloaded to the GPU. It’s not a perfect superimposition, but it’s still quite clear that fewer CPU resources are required when more of the user interface is handled by the GPU.

Here you can see the CPU usage over time whilst playing back one of the Cubase 12 demo songs. The lighter blue graph in the background is the CPU usage with software rendering in Cubase, where the darker blue graph in the foreground is the CPU usage if the rendering is offloaded to the GPU. It’s not a perfect superimposition, but it’s still quite clear that fewer CPU resources are required when more of the user interface is handled by the GPU.

Although the M1 Max and Ultra’s CPU cores make the most significant contribution to performance when running music and audio software, the silicon also includes GPU cores designed to offer the best possible performance for the Metal graphics and compute API. These cores are essential when running 3D modelling and rendering applications, or anything involving image and video processing, and benefit applications that render their user interfaces with Metal. For example, Steinberg specifically announced Metal support with the release of Cubase 11, which is why Mac users should have noticed Cubase’s interface becoming noticeably snappier and more responsive.

While you wouldn’t expect audio applications like Cubase, Pro Tools, Logic Pro and others to tax the graphics processing power of the M1 Max or Ultra in quite the same way as more visually intensive software like AutoCAD, Maya, Unreal Engine, and so on, that doesn’t mean you won’t see any benefit from the GPU. Using Cubase 12 as an example (because it’s easy in Cubase’s Preferences to toggle whether the GPU is employed for the user interface by the application), you can see from the graph that offloading the rendering within Cubase from the CPU to the GPU makes quite a difference to the CPU load.

Pros

- An elegant system that focuses on giving creative professionals what they want.

- Exceptionally quiet.

- The M1 Ultra represents some particularly clever silicon engineering.

- While not obviously ‘cheap’, the Mac Studio’s price tag isn’t unreasonable — especially since it can outperform current Mac Pro models in handling certain workloads.

Cons

- Like every Mac other than the Pro, it can’t be upgraded after purchase.

- Until fully optimised, native versions of applications and plug‑ins are available for Apple Silicon, you might not get the performance boost that would justify a new studio Mac right now.

- Shouldn’t the headphone jack be on the front?

Summary

Delivering both phenomenal performance and exceptional energy efficiency, the Mac Studio showcases the breakthroughs Apple have achieved by moving the Mac platform onto the company’s own custom silicon.

Test Spec

- Apple Mac Studio featuring an M1 Max (with 10 CPU cores, 32 GPU cores, and 64GB Unified Memory), 2TB storage, running Mac OS Monterey (12.3).

- Apple Studio Display.

- Logic Pro 10.7.3.

- Pro Tools 2021.12 with 2022.2 plug‑ins.