Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s performances on the tour featured seven musicians and numerous instrument changes. It was Elliot Mazer’s job to capture all this on tape. Photos: Joel Bernstein

Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s performances on the tour featured seven musicians and numerous instrument changes. It was Elliot Mazer’s job to capture all this on tape. Photos: Joel Bernstein

Forty years on, one of the most famous tours in history is now the basis of an epic live album.

In 1974 a band planned a tour of the US and England. Four years had elapsed since the release of their only studio album, and in the meantime, solo projects by the band members had met with mixed success. Yet demand for the group’s music was such that the 31 shows played by David Crosby, Stephen Stills, Graham Nash and Neil Young were planned on an unprecedented scale. Across North America and at Wembley Stadium in London, CSNY would play outdoor venues holding an average 50,000 punters. Stadium tours have since become commonplace — but at the time, this was revolutionary, both from a technical perspective and as a business proposition.

To handle the immensely complicated logistical side of things, the band’s manager Elliot Roberts teamed up with legendary promoter Bill Graham. The band themselves decamped to Neil Young’s California ranch to rehearse on a specially built outdoor stage, while the live sound on tour was entrusted to Young’s long-serving engineer Tim Mulligan. As the plans developed, Young came up with the idea of recording the shows for possible release, and again, he knew exactly the man to call.

Wheels On Fire

Producer and engineer Elliot Mazer first worked with Young on the hit 1971 album Harvest, and recorded numerous dates on his subsequent Time Fades Away tour. The 1972 album of the same title was taken entirely from these recordings, making it an unusual example of a live album consisting entirely of new material. And by 1974, Mazer had built one of the most advanced mobile studios in the US.

“His Master’s Wheel’s was my mobile studio. It had a Neve 8016 and a Neve BCM 10/2 ‘Melbourne’ sidecar. I worked on Bob Dylan and the Band at the Isle Of Wight Festival [1969]. Glyn Johns was the engineer. Those recordings sound great, and that is when and how I decided to use Neve in the truck.

“Monitor speakers were Klipsch Cornwalls, with Crown power amps, and a Sony small boom box which I still use for small-speaker reality. We had 1176s, but they and the Neve compressors were not used for this gig. Tape machines were Ampex MM1000s, with no transformers, and we ran at 30ips.

“The truck was laid out horizontally; the desks were mid-truck, and the speakers were on platforms and angled down. We had controlled power from a huge transformer.”

Doing The Splits

When Neil Young finds people he likes working with, they often end up part of his team for many years. This was true of both Mulligan and Mazer, who were thus able to collaborate fruitfully. In particular, Elliot Mazer was able to help specify the stage mics used on the shows, choosing models that he felt would produce the best recorded results as well as working well through the PA system.

Listening to playback inside His Master’s Wheels.

Listening to playback inside His Master’s Wheels.

“Tim Mulligan, who did FOH, and I had worked together for years. Tim and I worked great together and he knows Neil specially as he had been Neil’s live sound guy for a bunch of tours. We had many common mics that were split in our custom mic splitter. The splitter box on stage was built from high-end transformers by Magna-Tech, who then were the pre-eminent manufactures of film dubbers. We split most mics, and I had my own drum overheads and house mics. We had four mics in the house; they were planted by Denny Purcell, who then worked for the truck, before he became an amazing mastering engineer.

“The mics were Beyer M500s [hypercardioid ribbon mics] for voice, which sound great and reject unwanted sounds as well as any other mic. Drum overheads were Schoeps condensers. Those makes were made for distant pickup. We also used Schoeps in the house. Each drum was miked with [Electro-Voice] RE15s or RE20s. Snare probably had an SM57, and bass drum, some sort of dynamic. Amps and guitars were miked appropriately.”

Tour Of Beauty

CSNY performances on the tour could be anything up to four hours in length, and although the set list evolved as the tour went on, it always took the same general form. The band would begin with an ‘electric’ set featuring drummer Russ Kunkel, bassist Tim Drummond and percussionist Joel Lala. This would be followed by an ‘acoustic’ set in which the four singer-songwriters collaborated in varying combinations on each other’s material. Finally, a further ‘electric’ set would close the show.

Given that a single reel of two-inch tape running at 30ips lasts for only about 15 minutes, careful choreography was necessary to ensure that songs were not lost to tape changes. Typically, the second of the two recorders would be started one song after the first. “Tim and I had been to many rehearsals and I had recorded those guys earlier too,” explains Elliot Mazer. “We had two Ampex MM1000s running at 30ips. They ran together and were changed one at a time. We knew the song lists and set lists, and were able to plan appropriately.”

Five shows were recorded by Elliot Mazer: “We recorded two shows in Washington, two in Chicago and the Wembley show.” Thanks to the impracticality of shipping a mobile recording studio across the Atlantic, the last of these was recorded using the Manor Mobile, then equipped with a Helios desk. According to Mazer, however, the sound on stage did not vary a great deal from venue to venue — perhaps unsurprisingly given that the band were playing outdoors on huge stages. “The sounds were similar show to show, except for the house sounds. We were consistent. I knew how to record those folks and most things were similar night to night. Russ Kunkel is an amazing drummer and his kit always sounded great.” The Wembley shows were also filmed by the BBC, for a potential concert movie or TV special, but the footage was never aired.

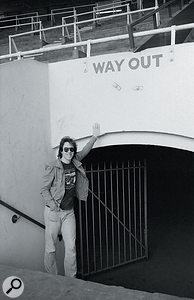

Elliot Mazer poses for the camera in Wembley Stadium, London.

Elliot Mazer poses for the camera in Wembley Stadium, London.

Out Of The Archives

Given the high profile of the tour, not to mention the success of CSNY’s earlier live album 4 Way Street, it was originally intended that Mazer’s recordings would form the basis of a new live album. The band themselves were enthusiastic, to the point where “I had added some more CSN voices in my studio in San Francisco after the tour. We set up a large PA in the studio to make the new voices sound real.”

Soon, however, the project became mired in the internal politics that have dogged the band throughout their career, and although Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young have recorded and toured since, the ’74 Tour tapes have remained in the vaults — until now. For the 40th anniversary of the tour this year, Rhino Records issued a deluxe three-disc box set taken mainly from Elliot Mazer’s recordings, lovingly recreating a typical 40-song set list from the tour. A bonus DVD includes selections from the BBC Wembley footage and from a bizarre experimental video system that had been installed at the Capital Centre in Landover, Maryland.

And regardless of the legacy of the tour itself, there has never been any doubting the scale of Elliot Mazer’s achievement in getting the proceedings onto tape. “I had decided a few years earlier that there is no reason why a remote recording should not sound better than a studio recording,” he says. And listening to the CSNY 1974 box set, there are plenty of moments — like the chill-inducing ‘On The Beach’, or the ferocious version of ‘Ohio’ that closes the collection — that bear out his conviction.

The Big Mix

Elliot Mazer’s CSNY 1974 master tapes were transferred to 24-bit/192kHz digital from a Studer A827, and mixed at Graham Nash’s studio by Nash, Stanley Johnson and Joel Bernstein, whose documentary photographs adorn the booklet that accompanies the CD. “The original masters were in great shape, considering they were already 36 years old,” says Johnson. “There was very little shedding — the heads were cleaned after every roll, and there was rarely ever any oxide or residue on the Q-Tips.

At Elliot Mazer’s suggestion, Beyer M500 ribbon mics were used for CSNY’s vocals, while all their acoustic guitars were amplified using Schoeps capacitor microphones rather than pickups.

At Elliot Mazer’s suggestion, Beyer M500 ribbon mics were used for CSNY’s vocals, while all their acoustic guitars were amplified using Schoeps capacitor microphones rather than pickups.“Mixing was a combination of computer and desk. I like to mix getting the levels from outboard gear and plug-in levels and run the mix bus as close to unity as possible. Elliot Mazer did a wonderful job of getting CSNY’s performance on tape and recorded with great dynamic range. Much of the ‘depth’ in the mixes started with the original recording; in mixing, we made sure we took advantage of those dynamics and augmented as much as possible.”When it comes to mixing a live album in particular, Johnson advocates letting the music do the talking. “Live mixing is defined by the balances and performance from the musicians. A great band and performance mixes itself if you get out of the way. With CSNY we knew we had great musicians and loads of energy coming off the stage. The live audience tracks were of huge importance to us for the final mixes. Tim Mulligan, the live mixer, did an amazing job every night and Elliot Mazer mixed a variety of mics in the house together onto a stereo pair on the 16-track machine to give us a great audience sound. Along with the band’s own dynamics on the stage, the mixes are very much a product of the delicate balance of the close mic tracks and the audience tracks. Unlike the guitars, the grand piano was sometimes amplified using a Countryman pickup system, but this often caused problems.“I spent lots of time listening to the audience tracks for, not only, the audience quality, but the ambience of the band in the building with the audience. In many ways, these tracks were like a guide for the final mix. There is a ‘sweet spot’ in the mix with the audience tracks and the band tracks: when you get to that spot, the energy of the band and the audience come together and ‘live’ takes over and a musical transparency takes over.“When mixing ‘live’ material, I have come tolove leakage. If you try and fight it you will lose, so I try to use it to my advantage, but it is tricky. Vocal leakage into an acoustic guitar mic can work well when both tracks are treated and balanced just right — did I mention phase? Perhaps one of the most useful tools in live mixing.”

Unlike the guitars, the grand piano was sometimes amplified using a Countryman pickup system, but this often caused problems.“I spent lots of time listening to the audience tracks for, not only, the audience quality, but the ambience of the band in the building with the audience. In many ways, these tracks were like a guide for the final mix. There is a ‘sweet spot’ in the mix with the audience tracks and the band tracks: when you get to that spot, the energy of the band and the audience come together and ‘live’ takes over and a musical transparency takes over.“When mixing ‘live’ material, I have come tolove leakage. If you try and fight it you will lose, so I try to use it to my advantage, but it is tricky. Vocal leakage into an acoustic guitar mic can work well when both tracks are treated and balanced just right — did I mention phase? Perhaps one of the most useful tools in live mixing.”

When asked about the challenge of ensuring consistency in a collection of recordings taken from different performances and venues, Johnson responds: “We were very fortunate to have Elliot Mazer as the live recording engineer! From night to night, the variable was more about the band’s stage blend and individual song performances, not great sound issues. We worked very hard to establish a way to keep the listener in the same ‘show’ for the entire concert — even though we did travel around a bit.

Visible in this shot is the miking used on Russ Kunkel’s drum kit, with Schoeps overheads.“Again, careful listening and treatment of the audience tracks from night to night was very important. We identified early on in the project our ‘favourite’-sounding hall and then aimed the other venues towards the qualities in that building. Width, depth and the size of the buildings then became the variables that we worked with to keep the concert and the listener in the same venue for the entire show. Fun stuff!”

Visible in this shot is the miking used on Russ Kunkel’s drum kit, with Schoeps overheads.“Again, careful listening and treatment of the audience tracks from night to night was very important. We identified early on in the project our ‘favourite’-sounding hall and then aimed the other venues towards the qualities in that building. Width, depth and the size of the buildings then became the variables that we worked with to keep the concert and the listener in the same venue for the entire show. Fun stuff!”

These days, one expects to see acoustic guitars and related instruments amplified using pickup systems, but almost all of CSNY’s instruments were miked, again with Schoeps capacitor mics. “On this tour, 1974, all the acoustic guitars were live miked — no pickups. It made for some mixing challenges but, in the end, we were very pleased at the sound of the guitars. I think they sound so much better than current-day direct/pickup acoustic guitars. I came to like the dynamics of the slight variation of sound when the players moved around a bit; it contributed to the ‘live’ feel of the performance I think.”

In fact, one of the more noticeable sonic compromises on the box set arose because of the lack of a microphone on Graham Nash’s piano; as a result, the mix of ‘Our House’ is nearly mono. “There were lots of issues with that track,” explains Johnson. “We worked to keep it ‘live’ and exciting, and also work carefully with a very problematic piano pickup as we did not have a mic on the acoustic piano for that night. The mix held together better when we brought it in to the centre a little more than maybe we wanted, but in the end, it is the song and the performance that is most important. It worked well.”