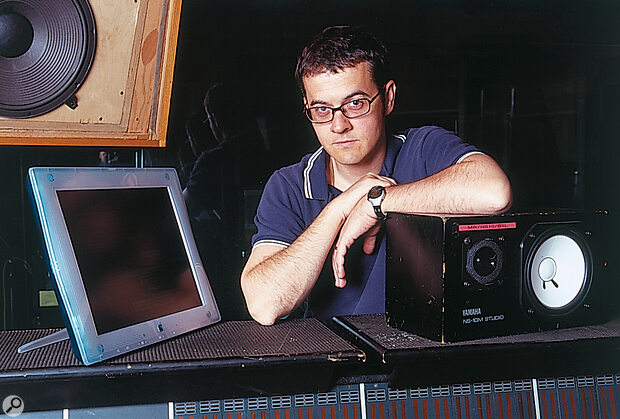

Sue Sillitoe talks to one of the most influential British record producers of the '90s, Stephen Street — the man behind a string of hit albums for The Smiths, Blur, The Cranberries, Catatonia, Sleeper, Shed Seven and many more.

The last time Stephen Street was interviewed by Sound On Sound was in July 1994, when he was enjoying chart success with Blur's Parklife and The Cranberries' Everybody Else Is Doing It So Why Can't We? Now, in 1999, Blur's latest album, 13, is their first without his expertise behind the mixing desk. I asked him if it came as a shock when Blur chose William Orbit to produce instead of him?

"It wasn't my choice. I just think they wanted to stretch out a bit more and having made five albums with me, the best way to do that was to work with someone different who would approach the project in a different way. I understand that perfectly and certainly wasn't offended. I did five albums with the band and I must admit I thought each one would be the last because they were bound to want to try something new."

Do you think this latest album is very different?

"Well, yes and no. People say that the style of 13 is different but I'm not so sure. For example, there's one song on the new album that was written in 1992, so they are still able to do things they touched on in the past. I think the goalposts moved more between The Great Escape and the Blur album, which was released two years ago. I count myself lucky to have been involved with that album because the band could have decided to go for a change of producer then. Yet I was very happy to be part of that album because, artistically, it was my favourite of the five I worked on."

Do you know how the choice of William Orbit came about?

"Oh yes — I saw it coming and wasn't at all surprised. After the Blur album came out the record company wanted to do the remix version, Busting And Droning, so they sent out tracks to various people including William Orbit and Moby to see what interpretation they would come up with. In my opinion, William's mixes were by far the best. He is a very talented guy. When I heard his mixes I thought if they want to go further down this avenue, then working with William would be a logical way to go."

What do you think of the new album?

"I like it, but then I'm a huge Blur fan. However, I can imagine why some people might be a little disappointed with the direction they have taken, because it is far murkier — in the sense that Damon's vocals are treated quite heavily and are quite subdued in the mixes, while Alex's bass lines are reduced to pretty much a subsonic rumble most of the time. It's not how I would produce it, but I still think its a good record and anyway that was the whole point. It will be interesting to see where they go with the next one — whether they will pursue this new direction or return to a more balanced view. With the Blur album we were able to be arty and experimental, especially with tracks like 'Essex Dogs', but at the same time it was counterbalanced with pop tracks like 'Beetlebum'. Hopefully they won't let that pop sensibility disappear too much."

The Producer's Role

The last time we met you'd just finished recording the second Cranberries album No Need To Argue. Have you worked with them since?

"No — they produced their third album themselves and have recently released a fourth. No Need To Argue wasn't a very happy experience. It has to be said that by the end of the album there was a bit of ego forming because Delores [O'Riordan] wanted credit as co‑producer. I didn't agree because I was employed to produce the album and, as far as I was concerned, that was that. Any band can turn round and say 'oh, we did a bit of co‑production because we brought this idea in here and that idea in there', but that's no more than I expect because you don't want to work with someone who is completely robotic. Just because the artist worked on a string line on a particular song doesn't make them the producer of the album. As the producer I am accountable to the record company and to the band, but mostly to the band because I want to make sure I'm deliver a good record. That's the pressure I take on when I agree to do a project and I take it seriously. There is a lot involved in being a producer — not least directing the artist throughout the recording stage so that I make sure they end up with an artistically strong record."

Does this mean you will never work with them again?

"Not at all. It was a shame to end that particular project on a sour note, but it hasn't affected my relationship with the band, because I still see them as friends. In fact I was recently asked to mix their latest album, and the only reason I didn't do it was because I had other commitments. But it just goes to show how things often come full circle. I could have been involved in that album had I been free."

How do you feel about coming to a project at the mix stage?

"I don't mind it now and again — in fact I find it quite refreshing. While I'm primarily known as someone who produces projects from beginning to end, it is quite nice to come in on something that has already had a lot of work done to it. If all the vocals have been recorded and everything else has been done it can be fun to sit there and think 'all I have to do is balance this and make it sound great'. It makes a change not to have to argue with singers about which is the best vocal take or worry about getting the drummer to sound good. Sometimes when I do this type of project I think 'wow, this is easy — and remixers get paid a fortune to do this!' But the difference is that remixers are under enormous pressure because they are perceived to be responsible for the success or failure of the track. Those guys are not only flavour of the month but also the last link in the chain — the ones who invariably get blamed if things go wrong. So, although I like dabbling from time to time, I'd still rather be known as someone who works with the bare bones and does everything, because I find that much more satisfying."

I'd rather have a great vocal slightly dodgily recorded than a pristine version of a bad performance. If someone has captured the moment, it doesn't matter if the vocal has a few imperfections.

And what about having your work remixed — do you mind?

"I don't mind so long as I've had the opportunity to mix it first. I object to people deciding halfway through a project that they are going to get the latest hip person to mix my work without giving me first refusal. Mind you, this doesn't often happen. Last year I did some tracks with Chrissie Hynde that Bob Clearmountain mixed, but I didn't mind because I knew about it in advance. I did initial mixes and Bob worked from those, using them for stereo placement and so on. He didn't change too much, which was reassuring!

"I did half the tracks on Chrissie's current album (Viva El Amor) and Stephen Hague did the rest. The tracks were recorded over a year ago, but it has been one of those albums that has gone through a long birth. I wasn't sure if any of my work would be used, but I'm delighted that so much has made it on to the finished album."

Irresistible

Don't you find it frustrating when record companies take a long time to release your work after you have finished it?

"Yes — very. Last year was an incredibly frustrating year because hardly anything I'd been involved in was released. That's just the way it works sometimes and you have to accept it, but the upside is that all of a sudden I've got a glut of work coming out. I did a variety of projects last year including two tracks with Liz Horseman who is a new singer songwriter, plus an album with a band called Tiger, which I think is one of the best I've ever made. I took that project after hearing their demos and liking them, but what clinched it was hearing about the line‑up of the band which was so wacky that I couldn't resist. They don't have a regular bass player because Dido — the bass player as such — plays everything on a Minimoog. They also have a female guitarist, Julie, who plays a guitar with only three strings all tuned to the same note! Working with Tiger was like going back to punk ethics, which was fantastic. There I was — a producer who has worked with the likes of Johnny Marr and Graham Coxon, who in my opinion are among the best guitarists in the world — and I was going into the studio with this girl who plays with three strings tuned to G or A depending on the key of the song! I think she learned guitar that way because it was easier and so she began writing songs to fit. It's amazing and it sounds really cool. I loved working with Tiger and I think we've achieved a stunning album. They have already released a single called 'Friends' that got some airplay but the market changed so much last year that I just don't think the moment was right to release the album. Last year was like that for a lot of bands — very much a watershed, with artists that had previously been selling well suddenly being dropped."

I understand you are also waiting for the Cupcakes debut album and the Ooberman debut album to be released.

"These were both projects I completed last year. Cupcakes are from Chicago, and it's quite rare for me to work with an American act, but when I went over to work with Lloyd Cole in New York I took the opportunity to go to Chicago to meet them because I'd been sent their demos and liked their interesting mixture of influences.

"The Ooberman album also came via a demo — this time from Blur's management company CMO. The band released a track last year through Graham Coxon's label Transcopic, but I thought the demo tracks were even better."

You have a reputation for taking on new artists and helping develop their sound. Is this deliberate?

"Not really, but it is something I enjoy. I like working with people when they are newly signed to see if we can take it to stardom or whatever you want to call it. If you do that you feel very much part othe act and that's what I'm most comfortable with."

You also seem to get a lot of return work.

"Without blowing my trumpet I've been fairly lucky with return projects, and I think it's because I tread carefully and go out of my way to make the recording process enjoyable. There's no point going into a studio and alienating the band just to please the record company, because it doesn't matter how big a hit you end up with, if the band didn't enjoy the session they won't ask you back — even if you give them a number one album.

"Some bands move from producer to producer because they prefer lots of different influences. Liz Horseman, for example, worked with different production teams on nearly every track because she wanted to experiment with diverse influences. It took longer to make the album as a result, but perhaps with solo singers like Liz it's necessary to adopt this approach because she doesn't have a band to bounce ideas off."

'Albatross!'

You have been described as the producer behind Britpop, thanks to your involvement with Blur, Sleeper, Catatonia, Shed Seven and so on — how do you feel about that?

"It was great when everyone was saying that Britpop was wonderful, but now it could be seen as an albatross around my neck. But I don't think of music in such a narrow way, because bands like The Smiths were effectively Britpop, only they came along 10 years before anyone coined the phrase. The way I see it is that I'm very pleased to have been part of the huge surge of interest in the music industry in the mid‑1990s. I'm glad that albums like Parklife exist. Back in the early 1980s it was only artists like Phil Collins or Tina Turner who sold enough albums to go platinum but now, thanks to Britpop, there are lots of bands having double, even triple‑platinum albums which is a big shift in the market. It's nice to be considered part of that."

"It was great when everyone was saying that Britpop was wonderful, but now it could be seen as an albatross around my neck. But I don't think of music in such a narrow way, because bands like The Smiths were effectively Britpop, only they came along 10 years before anyone coined the phrase. The way I see it is that I'm very pleased to have been part of the huge surge of interest in the music industry in the mid‑1990s. I'm glad that albums like Parklife exist. Back in the early 1980s it was only artists like Phil Collins or Tina Turner who sold enough albums to go platinum but now, thanks to Britpop, there are lots of bands having double, even triple‑platinum albums which is a big shift in the market. It's nice to be considered part of that."

Do you feel your style as a producer is changing?

"Certainly, but then I think that's inevitable. Every producer goes through periods of using too much reverb or making everything too dry or putting on too much distortion, but you keep yourself fresh by changingnd adjusting. Working with different engineers or in different studios is a good way of staying open to new ideas, although having said that when I find a studio I like I do tend to stick with it. I like Maison Rouge and Townhouse Studio Four and will work in either, depending on the budget, because acoustically I like the way the rooms sound. I also like the way the staff operate, particularly at Townhouse. Maison Rouge isn't as hi‑tech and smart, but it's a good workplace and I know I'll get good results. Sometimes I track there and mix at Townhouse, but again it depends on the budget. I made the Tiger album entirely at Maison Rouge last year, and was back there a few weeks ago with Lloyd Cole. In the US there's a facility called Magic Shop in New York that I like where they have an excellent collection of valve gear — Neve, Pultec, stuff like that — which makes it a great place to track. I did some demos for the second Cranberries album there and they turned out so well that we ended up using them on the album."

What equipment has caught your eye over the last five years and how has it changed your production approach?

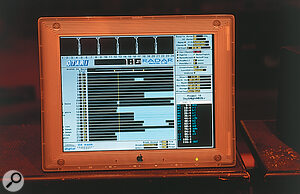

"The one piece of gear that has changed the way I work is the Otari RADAR. These days I use it all the time because I'm a complete fan. I bought one two years ago, soon after they were released, and used it on the Blur album. It sounded so good that it blew me away. Initially I bought 16 tracks but then added another eight for full 24‑track.

Stephen Street: "The one piece of gear that has changed the way I work is the Otari RADAR."

Stephen Street: "The one piece of gear that has changed the way I work is the Otari RADAR."

"I'm not into computers and fiddling about with a mouse because I think that kind of technology can get ithe way of the artist/producer relationship. But with RADAR, the remote sits on the desk and looks and feels like a tape machine, so people don't even think about it — it's just there recording whatever you are doing with the band. But the great advantage with RADAR is that it allows me to go back later and cut and paste the bits of the track that I like. This is such a creative leap that I can't imagine how I used to manage without it.

"RADAR played a huge part in the making of the last Blur album, and was probably instrumental in the direction they have now taken with Pro Tools, which was used extensively on 13. Tracks like 'Essex Dogs' began life as a 25‑minute experimental jam that was later cut down to eight minutes using RADAR, and we also used it for some of the drum parts on other tracks."

"RADAR played a huge part in the making of the last Blur album, and was probably instrumental in the direction they have now taken with Pro Tools, which was used extensively on 13. Tracks like 'Essex Dogs' began life as a 25‑minute experimental jam that was later cut down to eight minutes using RADAR, and we also used it for some of the drum parts on other tracks."

Home (And Away) Recording

Are you a fan of bands having their own studio technology at home?

"Bands can equip their own digital studio very cheaply now, especially when you compare it to the cost of doing this 10 years ago, so fitting out a home studio isn't a bad investment because it saves money that would otherwise be spent in expensive commercial studios. However, I believe it is important to use proper facilities for mixing, because you need a desk with automation and a decent amount of outboard gear.

"A lot of the bands I work with begin projects in home studios. Ooberman is a good case in point. They have a studio in Liverpool and use a Roland VS1680 digital recorder which is an incredible piece of kit. I was amazed by the sound they got from it and impressed by the amount of built‑in reverbs and delays. Because so many bands are starting projects in well‑equipped home studios, I am now finding that the demo material they present me with is of much higher quality and can often be used as a starting point for the recording session. If I like a demo I'll certainly use it. This happened with Ooberman and on the last Blur album with the track 'Strange News From Another Star'. In both cases the vocal performance was so nice and relaxed that I thought 'let's not mess with it; let's just add to it instead'. I am not trying to cop out by doing this — or take credit for someone else's work. I'm just reorganising what is good and taking it to the next level, which in itself is a production choice. This is where RADAR comes into its own, because it allows you to copy material from demos and then perhaps change the arrangement. RADAR has certainly transformed the way I work and is the one piece of equipment that I would be loath to part with."

...the great advantage with RADAR is that it allows me to go back later and cut and paste the bits of the track that I like. This is such a creative leap that I can't imagine how I used to manage without it.

I know you have a small home studio setup yourself. What equipment do you have in there?

"I have a small studio in a summerhouse at home which is equipped with a Mackie desk, some samplers and keyboards and a few trusty guitars including a Gibson 330 and a 1964 Fender Telecaster. I add new items quite slowly — the most recent being a [Mutronics] Mutator, which is a fun piece of kit — you can use it to add an analogue‑type filter to a synth sound.

"I also have a Mac with Logic, which is useful if I want click‑tracks, or to speed up or slow down a track, but I don't go in for heavy sequencing. For a bit of fun, I also recently bought an Akai MPC2000 because I liked the idea of having something that would enable me to get ideas together quickly. With the MPC2000, you have something that's a sampler and a sequencer, so it's pretty cool.

A selection of Street's gear: from top, TL Audio Classic dual valve EQ and Indigo VP2051 voice processor, Empirical Labs Distressor compressor, Emu Vintage Keys and Proteus FX synth modules, Yamaha SPX900 multi‑effects, Antares ATR1 Auto‑Tune intonation processor, Novation BassStation Rack, Zoom Studio 1201 effects, Mutronics Mutator filter bank, Ensoniq DP2 effects, SPL Transient Designer dynamics processor, and two more Distressors."My other recent purchase was a Zoom 1901 which has some good, lo‑fi settings and only cost £99 — last of the big spenders, that's me! And, of course, I have an Akai S3000 sampler that I bought a long time ago and still swear by. I just buy bits and pieces that I want to try out. For example, when I did the Tiger album I bought myself a Roland JV1080 because the band had used one on some of their demos and it sounded good. I thought I'd get one in for the sessions and then decided I might as well buy it."

A selection of Street's gear: from top, TL Audio Classic dual valve EQ and Indigo VP2051 voice processor, Empirical Labs Distressor compressor, Emu Vintage Keys and Proteus FX synth modules, Yamaha SPX900 multi‑effects, Antares ATR1 Auto‑Tune intonation processor, Novation BassStation Rack, Zoom Studio 1201 effects, Mutronics Mutator filter bank, Ensoniq DP2 effects, SPL Transient Designer dynamics processor, and two more Distressors."My other recent purchase was a Zoom 1901 which has some good, lo‑fi settings and only cost £99 — last of the big spenders, that's me! And, of course, I have an Akai S3000 sampler that I bought a long time ago and still swear by. I just buy bits and pieces that I want to try out. For example, when I did the Tiger album I bought myself a Roland JV1080 because the band had used one on some of their demos and it sounded good. I thought I'd get one in for the sessions and then decided I might as well buy it."

Do you ever bring bands to your own studio or do you always use commercial facilities?

"If I'm working with a band, I always use commercial facilities and take my equipment with me in SKcases. I use my studio for cataloguing samples and deciding what's worth keeping. It's also useful when I want to try out a new piece of kit because I think it's wrong to turn up at a session unprepared. If I'm trying something for the first time I'll bring it home and play with it for a while until I know what it's capable of and how it all fits together. The Roland JV1080 is a case in point — it took me a while to learn how to use it and I did that at home. I'm a great believer in messing around with the sounds that are in these boxes and trying to adjust them so they are more individual, rather than just using factory presets.

"The studio is also good for rough mixes and experimenting with drum loops. I have a pair of AR18 speakers which are great for playback, plus a pair of trusty Yamaha NS10s."

Do you prefer nearfield monitors to main monitors or do you use both?

"Over the last few years a lot of new nearfield monitors have come onto the market and some of them are good, but although I used to hate them at first I've grown so accustomed to Yamaha NS10s that they are the ones I've stuck with. Let's face it, if you can make something sound good on NS10s it will sound good on anything!

"However, when I'm in a commercial studio I do use the big monitors — which is why I like Maison Rouge and Townhouse Four. Both these studios have great monitoring. At Maison Rouge they have an Eastlake system using JBL horns and speakers that still sounds fantastic even though it's fairly old technology, while Townhouse Four has Genelec main monitoring, which I also like."

Stephen Street: "I've grown so accustomed to Yamaha NS10s that they are the ones I've stuck with. Let's face it, if you can make something sound good on NS10s it will sound good on anything!"

Stephen Street: "I've grown so accustomed to Yamaha NS10s that they are the ones I've stuck with. Let's face it, if you can make something sound good on NS10s it will sound good on anything!"

Do you have any new projects about to start?

"I've just finished producing and mixing the lion's share of a Lloyd Cole album and I had a lot of fun doing that. He is quite meticulous to work with, but I love his vocal style and his lyrics, which are incredibly strong — he's just one of those songwriters you can listen to again and again.

"Now that's finished I'm about to start work with the Longpigs, which should be good. Their first album took off a good year after it came out and then they spent a long time promoting it, especially in the US, so I get the feeling they are seriously ready to move on. The majority of the second album is done and I'm helping with the last couple of songs. After that, well — who knows? But I have no doubt something exciting will come along."

Stephen's Vital Vocal Tips

"It's important to record vocals in the right acoustic environment — whether that be at home or in a studio. The room mustn't be too reflective and of course you need a good condenser microphone. I like Neumann 87s and 47s, but I'm also not averse to trying a dynamic hand‑held mic like the Shure 58. I always record vocals with as little EQ as possible and I prefer to use proper EMT plates, or failing that, a plate setting on a Lexicon. The hardest thing is making sure singers learn mic technique. The mic can only take so much and even with the best compressor in the world I can't get around the sound beginning to break up if they are screaming too close to the edge of their range into a condenser mic. But in the end what really matters is the performance. I'd rather have a great vocal slightly dodgily recorded than a pristine version of a bad performance. If someone has captured the moment it doesn't matter if the vocal has a few imperfections.

"On the last few records I've been trying out the Antares Auto‑Tune unit. I know a lot of people got into Pro Tools because it had a particular plug‑in that gave them the ability to pitch up vocals and so on, but I wasn't interested in the Pro Tools way of working so I didn't go down that route. Instead I bought the Antares stand‑alone box because I wanted to see what it could do. I don't like using it for lead vocals, but it's useful for backing vocals. I don't think it's ever going to ever make a poor singer sound good because the only way to do that is to get the notes right in the first place, but for tidying up and sorting out wobbly bits, it's brilliant. Using this kind of technology is something one keeps quiet about though, because no vocalist wants to admit they need it, but believe me it gets used a lot more often than you might think, especially in emergencies. I find Auto‑Tune particularly useful for cleaning up vocals that have been recorded in home studios where the vibe is great but there are one or two notes that didn't quite cut it. Instead of having to do the vocals again and risk losing the vibe, it's possible to just nudge them along a little."