Richard Buskin meets a successful American composer who's specialised in a unique kind of music for television...

A prodigious worker, Shawn K. Clement has provided the music for a wide range of network television shows, including Buffy The Vampire Slayer, Dawson's Creek, Ally McBeal, Married... With Children, The World's Most Amazing Videos, The World's Wildest Police Videos, As The World Turns, Crime And Punishment, California Dreams and Ray Bradbury Theatre. However, it is in the genre of 'reality TV' that Clement has really made his mark. ASCAP recently paid due recognition to this by presenting him with the 2000 Film and Television Award for Most Performed Underscore, and Clement's music has adorned such only‑in‑America TV specials as Stupid Behavior — Caught On Tape, The World's Scariest Ghosts — Caught On Tape, Conspiracy Theory: Did We Land On The Moon? and When Good Pets Go Bad. Outside this specialist field, Clement has an equally impressive track record in cinema — he recently scored We Married Margo, an independent comedy feature starring Kevin Bacon, Tom Arnold and Cindy Crawford, with music that the composer describes as "every style known to man, including Latin, jazz, cartoon, circus and orchestral textures." Other recent film scoring projects include Last Chance, starring Tracey Walter and Tim Thomerson, and A Fate Totally Worse Than Death, starring Christopher Lloyd and Janet Leigh. Then there is the animated feature, 2004: A Light Knight's Odyssey, featuring the voices of John Travolta, Samuel Jackson, Christian Slater, James Earl Jones, Sarah Michelle Gellar, Anne Archer and Michael York, as well as a Batman video game for Warner Bros and the inaugural Donald Duck Playstation 2 video game for Disney.

Originally from Milford, Massachusetts, Shawn Clement started playing the guitar when he was 12 and subsequently moved to Boston to study at the Berklee College of Music. In 1993, he visited Los Angeles for the first time and joined a country band with a regular residency at the Roxbury club on the Sunset Strip. There he played sessions with such diverse musicians as Skunk Baxter, Don Johnson and Harry Dean Stanton, and the following year he relocated to Los Angeles... on the precise day that the Northridge earthquake came to town. Undaunted, Clement pursued his dream, and by 1995 his composing career had moved into high gear courtesy of the Showtime TV series Women, as well as The Savage Dragon, an animated series for Universal. He has never looked back, and recently moved his operations to his own recording studio called Clemistry Ranch in Canyon Country, just north of Los Angeles.

Acting On Impulse

"I take my first impulse and make it work," Clement explains. "I grew up playing in bands, so I have that whole psychology of being able to play all night in different styles. Some of the instruments that I have are just things that I've picked up as I go along, and I then find places for them in the music, using them in often untraditional ways. Sometimes I'll buy an instrument and find a way of incorporating it into the music, and at other times a director or producer might come to the studio and say, 'That's really cool. I want it,' and make a different creative decision.

"For instance, I've used the didgeridoo on a lot of different things. I can't play it very well, because to play it properly you've got to learn how to circular breathe, which I just cannot do. Therefore, what I've ended up doing is sampling it. There are tons of samples which you can already get, but it's a little different when you make your own, and I've used this on Buffy The Vampire Slayer, the Batman video game and all kinds of different things, just to get some weird low‑end growls and various kinds of tones."

Among the unusual instruments in Shawn Clement's studio is this theremin, custom‑built by Bob Moog.

Among the unusual instruments in Shawn Clement's studio is this theremin, custom‑built by Bob Moog.

Among the other wild and woolly instruments in Shawn Clement's extensive collection are an oud, an 11‑string lute‑lookalike with a wide neck and giant body which came all the way from Syria, and a waterphone, which basically looks like a metal jug with rods sticking out of it and produces bizarre feedback‑type sounds that are often heard on the soundtracks of suspense thrillers. Then there is his theremin, custom‑made by Robert Moog... "I've messed with it and I've used it on a bunch of different projects, but I have no idea what the hell I'm doing," Clement admits. "it's so hard trying to figure out where the notes are, I don't know how anyone plays it proficiently. Still, I used it recently on a trailer for an independent movie and it was really wild. I'll put it through distortion boxes and effects boxes to get some really way‑out sounds. Then again, when I did the movie A Fate Totally Worse Than Death, it was temped with old Bernard Herrmann scores and some of the stuff that I'd done for Buffy, and when the director came to my studio and saw the theremin I thought he was going to lose it! I ended up using it on a lot of the film and it was really, really cool. That was the first time I had to use it for real, employing it for its tonality."

Mention of Bernard Herrmann brings us to Clement's own influences in terms of film composition, for it was the music of masters such as Herrmann and Erich Wolfgang Korngold that he heard when watching thrillers and sci‑fi movies as a kid. "I watched a lot of those movies just because of the music, and that's how I learned to write," he says. "I was playing in all of these bands and I started making this weird fusion, writing really way‑out music. I watched a lot of old 50s sci‑fi movies and a lot of Hitchcock films, and that's how I really got a feel for Herrmann's sense of harmony and the way he moved around with his melodies. He was not necessarily this big, sweeping melody type of composer, but he had motifs where he'd move around with all the different instruments, and my style's a little bit like that. I don't have these big, long melodies. So, that stuff really had an effect on how I would write music. Most guys were buying Van Halen and Led Zeppelin records, and while I listened to that stuff too, I was throwing on Stravinsky and Bartok records and getting into full‑on scores.

"We all have our favourites, and to this day I just love Bernard Herrmann. He was one of the first film score guys who actually wrote for film. Most guys were writing pieces of music to stick into a film, but they didn't necessarily have anything to do with the movie. Herrmann would actually make music to fit the film, and while it might not stand up on its own as great music, it worked for the movie, and that was more important because that's what it was for. I just love how he had motifs that became the melody. The latest gig I did was this Batman video game, and we talked about making themes for all of the characters. Basically what I kept saying was 'You don't necessarily need a theme as far as the melody is concerned. It can be a riff, it can be a sound,' and that was directly related to my influences such as Bernard Herrmann."

We all have our favourites, and to this day I just love Bernard Herrmann. He was one of the first film score guys who actually wrote for film...

Finding A Direction

Shawn Clement doesn't work on riffs and motifs in advance of commencing a new scoring project. Instead, he derives his ideas from watching a TV show or film, and thereafter sits down almost immediately at a keyboard. "When I played gigs I would improvise solos, and that's how I approach a scoring gig," he explains. "You know, there are guidelines too. Before viewing the show I'll meet with the director and producer and they'll say, 'We want this, this, this and that.' Like when I did Buffy The Vampire Slayer once a week, there were pretty specific guidelines; 'OK, we want orchestral music. When it's scary, make it scary, and when it's funny make it funny.' Every week we would have spotting sessions where I'd sit down with the producers, the music editor and the post‑production assistants, and we'd be spotting for music and for sound effects and foley. Of course, my only concern was the music, so we'd go over the entire one‑hour show and I'd be told what they wanted in that regard. There might be specific things, but they'd basically rely on what I would bring to the table, seeing as it was my gig.

"I'd go home with that, knowing the parameters I had — what they wanted to hit, when they wanted a cue here, when they wanted a cue there — and then it was left up to my own head. Personally, I like some guidelines, if only for the simple fact that when you're scoring a project you have to satisfy that producer or that director, and the more direction he gives you, the better you can satisfy him. Because you can write an incredible score, but if it ain't the direction he wanted, when you play it for him he'll be going, 'No, no, no, no, no,' and you've wasted a lot of time and you also look bad. Guidelines tell me what direction he wants, and even though I may not like that direction, I have to satisfy him."

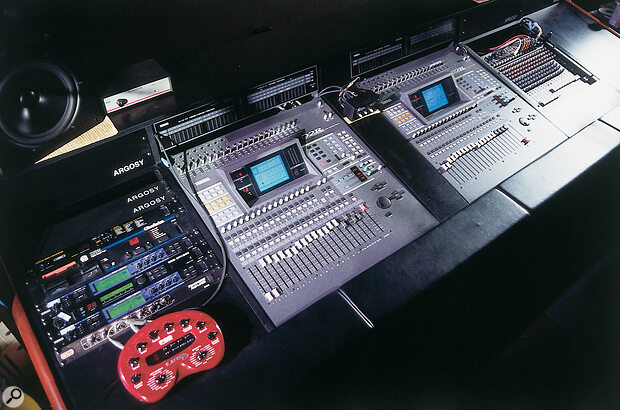

Home on the ranch: Shawn Clement's studio at Clemistry Ranch is based around two Yamaha O2R digital desks and Genelec 1032 monitors. To the left can be seen his main outboard rack and Line 6 Pod guitar preamp.

Home on the ranch: Shawn Clement's studio at Clemistry Ranch is based around two Yamaha O2R digital desks and Genelec 1032 monitors. To the left can be seen his main outboard rack and Line 6 Pod guitar preamp.

Still, are there not times when Clement feels compelled to express his extreme dislike for a desired direction? "It depends on the job," comes the reply. "Sometimes I will. For instance, on a lot of the reality shows that I do, I have a lot more freedom. They'll say, 'We're looking for this,' and I'll say, 'Nah, it's the wrong way to go,' whereas on a show like Buffy the producer gets what he wants. And sometimes he's right, sometimes he's not."

For his part, Clement admits to occasionally being clueless rather than inspired when viewing some footage that requires scoring. In such cases, the common factor tends to be a scene that everyone has been having problems with. "On Buffy there was an episode called 'Phases', which I guess was doomed from the beginning," he recalls. "No‑one was happy with the writing, no‑one was happy with the acting. It was just a bad episode, there was no time to do anything about it, and the basic direction for the music was 'Look, you need to save the show. You've got three days.' That was a little puzzling, because what could I do? I mean, when I watched the episode I saw the problems that everybody else saw, so it was a really tough thing to do.

"I thought my ass was on the line — you know, 'If I don't save the show, I'm gonna be canned!' That's why I decided for once to do everything I could to make people totally ignore the visuals. What I did was to go a little bit over the top on it, and while I don't know if I saved the show, it actually ended up being a really popular episode. One of the problems was that there was a character who turned into a werewolf, and the makeup looked really bad. The joke on that show was that he looked like an oversized groundhog. So, to try to avert attention from that, I just made really huge, crazy music, which is not something I would normally do."

Normally, however, Shawn Clement asserts that experience has taught him to ensure that music should never get in the way of the on‑screen action. "Music is another actor in the film," he says. "It creates an alternative form of dialogue to reinforce the visuals." That being the case, the aforementioned 'Buffy' assignment was an undoubted exception to the rule.

Locking On

Something Clement strives very hard to avoid is having to rewrite his music to accommodate late changes of mind from producers and directors. "Some guys have got to do rewrites all the time," he says, "but these days, before going into a project, I try to see how the producers are, and if I sense that they're the type who will want extra cues for no reason, I won't take the gig. it's too much craziness."

To avoid having to rewrite, Clement insists at the start of a project that he will only work to a locked picture. However, this stipulation often creates its own problems, not least when the show isn't locked until three days before delivery. "I'm left with very little time," he says. "However, if you start working without a locked picture it gets impossible, because things keep changing all the time and you're just doing three times the work. You have to retell the story and you get burned out. I mean, when I write music for a scene, in my head there's only one way I can write that scene, so if I have to keep rewriting it I'm going to be fried.

This work area contains Clement's Korg M1 workstation, a Peavey StudioMix controller used to manipulate controls in Cakewalk, and a vintage Emu Emulator II sampler.

This work area contains Clement's Korg M1 workstation, a Peavey StudioMix controller used to manipulate controls in Cakewalk, and a vintage Emu Emulator II sampler.

"It's a tricky situation. Like I did this ridiculous reality show, a special called Stupid Behavior, and basically it required 45 minutes of music wall‑to‑wall. Well, they kept recutting it and recutting it, and I eventually got the show and had four days to do it. Then, on the fourth day, they showed up at my studio with yet another completely recut version of the show. I was like 'Whoa!' I wasn't even finished writing it yet, and I already had to go back and start fixing what I'd done..."

At least they didn't expect everything to still be completed on that fourth day, did they? "Oh yeah! This was a Tuesday, the mixing was on Wednesday and it was on television on the Thursday. There was no time. It was ridiculous! In the end I had to bring in a music editor. There was no other way to do it, having to re‑edit the cues I had already written so that they would fit the new cuts of the scene. Talk about stupid behaviour!

"it's equally as hard to deal with footage being inserted as footage being deleted. It just depends on what it is. For instance, if you're doing a techno kind of music with lots of loops going on and they start altering the length of the piece, your rhythms and your times may not work anymore. Now you have to go back and reprogram, and that can be a nightmare. You know, the worst is an editor saying, 'Well, I only took out a few frames here and there.' They think it's no big deal, because editing is basically non‑destructive. They can go back to the original at any time, and they don't understand that when you're writing a piece of music, it's done. If you add four frames here and five frames there, that's worse than just taking a big chunk out, because now everything's off. You can fix one section and the rest of your cue won't work. it's bad."

Just Another Day At The Office

Among Clement's longer‑term gigs has been Fox Television's reality show The World's Wildest Police Videos, which he has worked on for the past five years. A fairly routine project, it perfectly encapsulates his approach to music scoring. "After getting the tape, watching it and deciding what to do, I'll start with a piano sound," he explains. "The Yamaha P200 is my controller, and the sounds actually come out of my GigaStudio 160. I used to use the Kurzweil K2500, but then I got the GigaStudio and the piano on that is unbelievable. I'll just use that as my working instrument, and when I'm scoring a scene I'll generally start with rhythmical ideas. So, sometimes I'll start with percussion coming out of my Kurzweil, my Emu or any one of my samplers, and at other times I might come up with some kind of phrase or motif or bass line. Basically, I'll come up with the main groove, thinking about it like I'm writing a song, and getting a sense of how the rhythm will go and what the tempo's going to be. With a reality show the tempo's really important, because you're making it exciting and you want to hit all of the things that go on. You're going to nail a lot of things with music. So, I'll be coming up with the tempo of the piece and the general rhythm of the piece.

"At this point the basic rhythm track won't run all the way through, just up to a certain point, and it will provide me with a general concept. For instance, I'll watch the whole cut — which might be three minutes long — and then I'll go back and make a mental note: 'Well, my first big hit's going to be three seconds in, so I'm going to write for those first three seconds.' I'll go and get the actual frame that I'm going to hit it at, and I'll make sure that it's in time. Then, having written everything up to that first point, I'll go from there to the next point. Mentally I do come up with a general piece, but the thing with reality shows is that on a lot of them you'll hear these groove beds and people will throw in hits where they need them. That's very boring, so I try to score it like a scene in a movie.

"That Wildest Police Videos show is actually a hard one to work on, because it's the same stuff all the time, and so essentially you're writing the same tunes every week. You can only do that so many times before you're wondering what the hell to do next, and then there's the running joke about the executive producer; 'OK, we want you to score this using no instruments.' He hates every instrument, so it's really difficult. I mean, what the hell are you going to do? That makes the gig hard, and now they're starting to do different types of pieces, which means I have to write different types of music, but they're so narrow in scope in terms of the style that they will allow. That makes it really hard."

Movies, Games & TV

Shawn Clement's general modus operandi when writing music for film or television is pretty much always the same. However, he considers movie scoring to be far easier than that for a TV show. "In a movie yo u have a lot more time to develop themes and create a whole mood," he explains. "Basically, you have more time overall, whereas TV's a little bit harder because for an hour‑long drama with 44 minutes of screen time you've got a 20 or 25‑minute score, and you have to tell that story. You're supposed to develop themes for every character, just like you would for a movie, but you have a shorter timeframe, and you can't make it sound like it's jumbled. You also have only three days to do it, and then after that you've got another one to do right away. Week after week, show after show, is a lot more difficult than a movie. You can be working on a movie for three weeks or six weeks, and during that time you're able to sit down and focus on just one situation. To me, that's the biggest difference.

"The video‑game format, on the other hand, is really different. That and reality shows are the two most difficult things I've ever had to write music for. You see, with the video game it's a double‑edged sword. You get a lot of time to work on a video game, and in one way that is a good thing — when I did the Donald Duck game for Disney I was on that for six months. That meant I had a lot of time to develop my theme, but the problem is you have to stay with that music for six months of your life, and if you take on other gigs in between, as I did, it's hard to keep getting back into Donald Duck world.

"The reason why it takes so long is that they're physically making this game, so as they finish different sections, you're given these to write music to and then you've got to wait. You write the next theme and then you've got to wait. it's stretched out over a long period of time, so you're constantly going back — it's like a never‑ending job. That's just the nature of the beast. The other really difficult thing about writing a score for a video game is that you don't know what the player's going to do. This means you have to come up with a piece of music that's really cool, and it has to loop without getting boring. Then, when a player does get to a certain point in the game, the music's going to switch to another cue, meaning you have to be able to design this cue so that, from any plane, it can jump to a little transition piece that you've written, connecting to the next cue. You have no idea when that's going to happen, so you almost have to become like a mathematician, and that's really hard. You've got to write a lot of cues.

Shawn Clement's master keyboard is a Yamaha P200, and he also has an extensive collection of samplers. Two Akai S6000s occupy the rack to the left of the computer, while that on the right contains two Emu E6400s as well as a Kurzweil K2500R sound module.

Shawn Clement's master keyboard is a Yamaha P200, and he also has an extensive collection of samplers. Two Akai S6000s occupy the rack to the left of the computer, while that on the right contains two Emu E6400s as well as a Kurzweil K2500R sound module.

"On the Donald Duck game there were about 60 minutes of music, and for that I wrote between 80 to 90 pieces of music, all of which had to be interchangeable, related to each other, and continuing similar themes. It was so much work, and being that it was the first video game I'd ever done, I was going, 'Oh my God, this is a nightmare!' Like anything, after doing it once you learn a lot, but it's really hard and I'd never realised it."

In November 2000, immediately after completing the Donald Duck project, Clement started work on the Batman video game for Warner Brothers, and at the time of our interview five months later he was still involved with it, having waited two months for delivery of the next section. "They want this big, dramatic music, so I've got to make this big, dramatic movie‑like cue which has to loop, and that's not easy," he says. "The producers for this kind of project are very specific, although in different ways to movie and TV producers. They talk about the themes and the stylistic and sometimes even the instrumentation that they want, but they're more about 'OK, I need a two‑second section, then I need a ten‑second section and a 30‑second section. That's gonna loop, that's gonna loop, that's gonna loop, and they're going to be connected together.' It really gets to be like a grid, and every cue is like that. So, they are very specific. I get sheets and sheets of paper containing very specific technical data regarding what must happen with the music.

"As for the music itself, with a video game it's a lot more over the top and lot more bombastic than with a TV show or movie, because you're essentially creating all of the excitement. I finally just received my copies of the Donald Duck game — I never once saw it while I was working on it. There were some cartoons that I scored to picture, but I never saw the actual game. So, I finally got it, I was playing it, I got caught up in the game, and it was really interesting because the music was actually making it frustrating. You know, it's going all the time and it's creating all that anxiety. it's over the top and it's ridiculous, but you want the player to be excited.

"When you're writing the music you have to be aware of all of the sound effects. I tend to use lots of tracks when I score, I'm a very notey kind of person, and so that was hard because I had to keep asking myself, 'If they're going to have all those sound effects, how is that going to mix?' I mean, there's so much stuff going on, it's crazy. For instance, one of the characters in the Batman game is the Joker, and they just said, 'Well, we need some kind of Joker music.' So, I thought about it and decided to use some circus clown instruments. I picked up a bunch of slide whistles and a thumb piano, and these are what I used for cues like the one called 'Joker's Letter'. That whole cue was done with slide whistles, a thumb piano and percussion instruments. I had total freedom, so I could be totally experimental and just do whatever I wanted, using effects and doing weird things with them. I had a great time."

"Are there projects," I ask, "where you basically feel like music is the last consideration?"

"All of them are like that," Clement replies without hesitation. "The only exceptions are the video games. With them the music is the last consideration in terms of the budgeting, but not in terms of the project itself. Those guys really care about it. However, with all of the other projects music is absolutely the last consideration. I mean, you'll meet with them and they'll tell you, 'The music is really important here. We need this, this and that.' Then they'll go, 'We need it tomorrow.' I'm like, 'What? Are you kidding me?' I always think it's the last thing on their minds, even if to me it's one of the most important things on the project. After all, it can make or break it..."

Shawn Clement's Cardinal Do's & Don'ts Of Scoring Work

- "Never say you can't do something, because that will get you fired. They'll automatically not like it, no matter what you write. So, you can be scared about it, but don't let them know that. The second you start sounding hesitant, it freaks them out."

- "Really figure out what they do and don't like. If they don't like something, don't keep redoing it, because regardless of your personal tastes, your boss is always right."

- "Conversely, don't ask too many questions! Only ask the key, important things. They're hiring you because you're a professional at what you do. You're supposed to know your job, so if you start asking them too many questions they won't trust you any more."

- "Don't waste any time on bad ideas, but if you have wasted time then just make it work, because you can't start over."

Into Guitars

While much of Shawn Clement's music is synth‑based, his contributions to the family drama Dawson's Creek revolve more around the acoustic guitar, not least because the music serves as a backdrop rather than as a scene enhancer. However, even though Shawn Clement is a seasoned player and avid collector of guitars, he hates doing guitar pieces, citing the fact that they entail a lot more work. "When you're using MIDI it's easy to fix things and easier to make them sound good," he says. "When it comes to record guitar, first you've got to get it sounding good, then you've got to get it miked good, then you've got to make sure you play the part right. You can't fix it, and it takes a lot more time. What's more, you might be getting the part right and then the guitar will go out of tune. It's so much work I dread it, and I'm a guitar player! For that reason I've always written music that does not involve guitars."

Shawn Clement: Selected Studio Gear

RECORDING

- AKG C414 and SolidTube mics.

- Apogee AD8000 converters.

- Genelec 1032 monitors.

- Line 6 Pod guitar preamp.

- Mackie 1604 mixer.

- MOTU MIDI Timepiece AV.

- PCs running Cakewalk Pro Audio and Nemesys GigaStudio 160 with Frontier Design Dakota and Montana soundcards.

- Shure SM57 and SM58 mics.

- Tascam DA88 digital multitrack.

- Yamaha O2R digital mixer (x2) with ADAT and TDIF cards.

- Yamaha NS10m monitors.

OUTBOARD GEAR

- Yamaha REV500 multi‑effects (x2).

- Yamaha SPX990 multi‑effects.

- Lexicon LXP15 multi‑effects.

- Korg DRV3000 multi‑effects.

- 1960s Tube Echoplex.

SYNTHS & SAMPLERS

- Akai S6000 sampler (x2).

- Emu E6400 Ultra sampler.

- Emu Emulator 2 sampler.

- Korg M1 workstation.

- Kurzweil K2500R sound module.

- Roland S760 sampler.

- Roland JV1080 sound module.

- Yamaha P200 master keyboard.

- Yamaha VL70m sound module.

Clement also has about 40 different instruments, including more than 25 guitars, and the following more unusual instruments:

- Sitar.

- Digeridoo.

- Oud.

- Waterphone.

- Theremin.

- 5‑string Deering banjo.

- Coral sitar.

- 8‑string Fender lap steel.