We're used to hearing rock albums reworked by electronic producers — but Alanis Morissette chose to do things the other way around...

Joe Chiccarelli at Sunset Sound.Photo: Ana Gibert

Joe Chiccarelli at Sunset Sound.Photo: Ana Gibert

Some time in the second half of 2011, producer Joe Chiccarelli accepted an unusual assignment. He was presented with what was, in essence, a finished Alanis Morissette album, and was asked to reinterpret the tracks as he saw fit. "Alanis' managers played me a few songs and I loved them,” Chiccarelli recalls. "They said that they and Alanis didn't want to exactly remake her previous album, Flavors Of Entanglement, that they wanted to do something a bit different. They wanted to keep to the modern feel of the tracks, but humanise them, give them more edge. In every other respect I more or less had carte blanche. I said, 'Look, I'm a big fan, I love what she does, I'm happy to be involved.'”

The tracks for the new album had been co-written by Morissette with Guy Sigsworth, and the latter had also recorded and comped the vocals, programmed the arrangements and produced everything. Apart from some guitars played by Sigsworth's engineer Chris Elms, nothing had been done on 'real' instruments. So, over three months during the winter of 2011-12 at Sunset Sound Studios in Los Angeles, Chiccarelli set about reinventing the songs, using a group of studio musicians, including several members of Alanis' live band. "I recorded the musicians, changed some of the arrangements, restructured some of the songs, added new sections, replaced some of the parts with live musicians, and so on. In some cases I kept a lot of the programming, in other cases nothing remained. Essentially, I put up the vocal, and built new arrangements around it, sometimes using elements of the original arrangements. It felt like I was taking the remix version of the album, and going back inside the tracks to do the original album. It was like reverse engineering.”

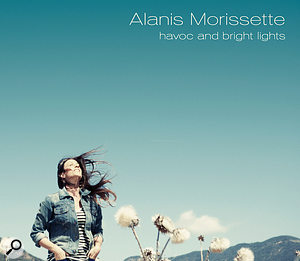

The end result was Morissette's eighth studio album, Havoc And Bright Lights, which was released in August, more than four years after its Sigsworth-produced predecessor. The long hiatus was marked by the singer giving birth to her first child on Christmas Day of 2010. Havoc And Bright Lights contains 12 songs, six of which were produced by Chiccarelli alone, three by him with additional production by Sigsworth, and three by the two equally together. Sigsworth's original tracks were fully realised in his own signature electronic style, which he has also used to great effect in his work with Björk, Seal, Madonna, Bebel Gilberto, Kate Havenevik, the Sugababes and Britney Spears: delicate, airy electronica. Chiccarelli's reworkings, by contrast, have all the hallmarks of 21st Century rock & roll: grittier, brash, with lots of distorted electric guitars, augmented by electronic wizardry from Sigsworth and others.

Home From Home Studio

Chris Elms (left), Alanis Morissette and Guy Sigsworth during the initial making of Havoc And Bright Lights.

Chris Elms (left), Alanis Morissette and Guy Sigsworth during the initial making of Havoc And Bright Lights.

Sigsworth and Elms are based in London, and the duo travelled three times to Los Angeles during the Summer and Autumn of 2011 to write and record in a makeshift studio in Morissette's house. They then spent a further two months in Imogen Heap's studio in Essex (Sigsworth's own London studio was not in use at the time) completing and mixing the tracks for what they thought would be the finished album. Sigsworth: "For the previous album, Alanis and I had written the songs in my own studio in London and The Village in LA, but because she had just become a mother she was quite housebound, so we decided to create a setup in her house. One of the joys of modern record-making is that you need very little to get going. We had a MacBook Pro and my favourite monitors, the Dynaudio Air 6 monitors, and Alanis' favourite microphone, the AKG C12.”

Chris Elms, who has worked for Sigsworth for three years, and before that attended Brit school in Croydon and played live guitar for Leona Lewis and Katie Melua, adds, "This may disappoint readers, but I'm very much of the school that if I can get it into Pro Tools, I can always fix it! A baby crying or dogs barking didn't deter us from doing a vocal take. The main thing that matters to me is that the signal chain is clean and as short as possible. I hate patchbays, splitter boxes, and spaghetti wiring. When I'm recording a vocal, I want to see the cables that go from the mic into the mic pre and the mic pre into the interface. That's the only way I feel in total control of the entire chain. So for the vocals we fed Alanis' AKG C12 into a Universal Audio 6176 channel strip that we borrowed from the studio of her husband [Mario 'MC Souleye' Treadway]. I used that purely as a mic pre and switched the 1176 half of it off. It went straight into the [Avid] 192. Really simple.

The initial sessions for the album took place in an improvised studio at Morissette's house. Many of the vocal takes from these sessions survived Joe Chiccarelli's reinterpretation."For monitoring, we used the Waves Renaissance EQ to cut some bass and add some treble, and the Renaissance Compressor to hold the level. Alanis loves to sing with loads of reverb, and we used the [Avid] Reverb One for that, with a very strong de-esser in front of it. Some of the electric guitars I played remain on the record, and I recorded those via Guy's Focusrite Platinum Tone Factory, which sounds really clean. Guy and I agree that [Native Instruments'] Guitar Rig 5 rules in the box! The Rammfire amp is super-heavy, and we love the really low detuned parts. Check the deep guitars on 'Guardian'. I had both Logic and Pro Tools open pretty much all the time. If an idea started on a guitar, we'd use Tools, if Guy started with a beat or a bass line, we'd opt for Logic. From memory, 'Guardian', 'Woman Down', 'Celebrity' and 'Edge Of Evolution' started in Logic, but every song had some Logic in it, whether it be an ESM, ES2 or ring-shifted Structure patch.”

The initial sessions for the album took place in an improvised studio at Morissette's house. Many of the vocal takes from these sessions survived Joe Chiccarelli's reinterpretation."For monitoring, we used the Waves Renaissance EQ to cut some bass and add some treble, and the Renaissance Compressor to hold the level. Alanis loves to sing with loads of reverb, and we used the [Avid] Reverb One for that, with a very strong de-esser in front of it. Some of the electric guitars I played remain on the record, and I recorded those via Guy's Focusrite Platinum Tone Factory, which sounds really clean. Guy and I agree that [Native Instruments'] Guitar Rig 5 rules in the box! The Rammfire amp is super-heavy, and we love the really low detuned parts. Check the deep guitars on 'Guardian'. I had both Logic and Pro Tools open pretty much all the time. If an idea started on a guitar, we'd use Tools, if Guy started with a beat or a bass line, we'd opt for Logic. From memory, 'Guardian', 'Woman Down', 'Celebrity' and 'Edge Of Evolution' started in Logic, but every song had some Logic in it, whether it be an ESM, ES2 or ring-shifted Structure patch.”

Sigsworth adds, "I'm quicker in Pro Tools, but I think it's easier to throw a track together from nothing in Logic if it is very synth-based. Using Logic had mostly to do with the soft synths, particularly the ES2 — it's amazing what you can do with that. In general, we have the same stuff everyone has, and I'd like to think that the personality comes from the aesthetic choices that we make. But I am a big fan of [Modartt] Pianoteq, because of the way it allows you to mess with the sounds, and also because it's based on physical modelling rather than samples, so it's not going to crap out on you when you're playing a large chord or are using the sustain pedal a lot. Massive sample libraries are great, but it's still great to have things that are lean, and Pianoteq is very lean! It's also to do with my taste in pianos: bright pop pianos turn me off, I prefer mellower piano sounds. In addition, I love all the Native Instruments stuff, especially the Massive synth and Kontakt, which is the default sampler that I use for everything. I also have the Arturia CS80 and quite enjoy that. Beats we usually began by dragging audio onto the screen and chopping that up, or to pull in a loop if we wanted get a groove more immediately. In cases where we wanted to make the drums sound like a real drummer, we went for [Toontrack] Superior Drummer, [XLN] Addictive Drums and Steven Slate Drums.”

The Heat Of The Moment

Once they had Morissette's contributions recorded, Sigsworth (left) and Elms decamped to the latter's London studio to finish — as they thought — the album.

Once they had Morissette's contributions recorded, Sigsworth (left) and Elms decamped to the latter's London studio to finish — as they thought — the album.

On both albums Sigsworth and Morissette have written together, their preferred method of writing was for the former to knock up some backing tracks, over which Morissette improvised melodies and lyrics. Sigsworth says: "The important thing was to give her three ideas to choose from, and she would immediately pick one. She obviously also has ideas in her mind where she wants to go lyrically. Sometimes I put more music on than was necessary, and we'd later on strip stuff back again, making sure the track harmonically complemented where she had gone melodically. It's tricky writing song-starter inspiration sketches. You need enough music to create a vibe, but you still need to leave space. I've sometimes written amazing backing tracks, but they sounded too self-sufficient to let a singer into them. Sometimes a sketch with just a piano and a weird electronic noise inspires a writer more than a symphony.”

Elms: "Guy and I would get to the studio early, and knock up three or four ideas in a couple of hours. Alanis would choose one and we'd start recording straight away. Sometimes Guy would be playing live keyboards with Alanis singing, and my goal was just to record everything and always be ready for a change in key or tempo. Alanis is very instinctive and in the moment as a writer, so I had to make sure to always be in record mode, to make sure I didn't lose anything. At various points, Alanis would say, 'That's a verse,' or 'That's the last line of the chorus,' and I'd immediately make markers and notes to keep track of everything. We would then bounce these sketches onto Alanis' laptop for her to write her lyrics to. At this point, we'd also transfer everything to Pro Tools to make sure we were ready to record her master vocal takes. She writes lyrics very quickly, so there was a lot of pressure. We'd then make rough comps of her vocals. Listening back at the end of the day to what we had done, I was always struck by how big these demos sounded. Ninety percent of the parts remained in the final productions we delivered.”

Finishing The Album The First Time

Back in the UK, Sigsworth and Elms set about turning the songwriting sketches and Morissette's vocals into finished articles. On Flavors, Sigsworth had used additional musicians for drums, bass, strings and guitars, but he decided to realise the new project just with Elms. "Yeah, it was just Chris and I doing those tracks. Chris plays guitar really well, and I liked the idea of it being just us. I often have a creative vision for a track from early on, and wanted to realise these visions myself. Like on the song 'Havoc', my idea was for all sounds to be piano sounds, with different piano sounds going through different effects, a bit like on a Harold Budd record. Also, my experience is that unless strings are the main feature in a track, the fake stuff actually sounds fine. We recorded real strings on Alanis' previous album, but afterwards I edited pretty much every note, which is very time-consuming.”

Elms adds: "During mixing, Waves plug-ins did most of the heavy lifting. In TDM they are super-reliable, and in RTAS they are super-efficient! I can have hundreds of instances of Waves plug-ins open and the Mac won't struggle at all. Other plug-ins we love are the Valhalla Shimmer, which can turn any sound into a thing of beauty. The Izotope RX2 plug-in also got a lot of work, especially the Spectral Repair Module. You want to remove a dog barking or baby crying from a vocal take? No problem. Most of the vocals that Guy and I recorded and edited remained on the final record, and it sounds like my plug-in chain remained intact, as did things like the reversed guitars I played in 'Spiral', the Valhalla reverb effects on the piano in 'Havoc' and the synth programming in 'Woman Down'.

"Alanis' mix vocal chain began with a [Waves] Q10 with each frequency automated. Basically, I'm taking out the fundamental frequency [of each note] so the higher harmonics cut through. The vocal sounded less boomy as a result, and I could make her louder and she'd still sound embedded in the arrangement. Next was the Renaissance EQ with just a high-pass to take out unwanted low rumble so it didn't affect the compression, and then a Pultec MEQ5 notching out at 500Hz, which helped to warm her vocals a little bit and added a slightly creamy analogue tone. After that, there was compression from the Waves CLA3A to take out the biggest peaks, followed by the Sonalksis SV315, set to a low ratio and slow attack to hold the vocal further without destroying any detail of the performance. Sometimes I'd use the Renaissance Compressor instead of the CLA or the Sonalksis. I compress mainly for tonal quality, and did a lot of detailed vocal riding for volume control, which creates a real sense of intimacy.”

"Alanis' mix vocal chain began with a [Waves] Q10 with each frequency automated. Basically, I'm taking out the fundamental frequency [of each note] so the higher harmonics cut through. The vocal sounded less boomy as a result, and I could make her louder and she'd still sound embedded in the arrangement. Next was the Renaissance EQ with just a high-pass to take out unwanted low rumble so it didn't affect the compression, and then a Pultec MEQ5 notching out at 500Hz, which helped to warm her vocals a little bit and added a slightly creamy analogue tone. After that, there was compression from the Waves CLA3A to take out the biggest peaks, followed by the Sonalksis SV315, set to a low ratio and slow attack to hold the vocal further without destroying any detail of the performance. Sometimes I'd use the Renaissance Compressor instead of the CLA or the Sonalksis. I compress mainly for tonal quality, and did a lot of detailed vocal riding for volume control, which creates a real sense of intimacy.”

Flying Blind

It was only after Sigsworth and Elms had put in all this hard work that Joe Chiccarelli became involved. The nine-time Grammy-winner has a very impressive track record, having worked with the likes of Frank Zappa, The White Stripes, My Morning Jacket, the Shins, Elton John, the Killers, Beck, U2, Rufus Wainwright and more. Chiccarelli and Sigsworth never met or communicated, so the American started his part of the project without being aware of any of the details of the two Britons' work. Sigsworth and Elms simply sent him Pro Tools Sessions of all the songs, sometimes with all parts separated out on individual tracks, sometimes with them combined into stems, but always with a finished lead vocal. Chiccarelli set to work in Sunset Sound to reinvent the arrangements and production for each song — with Morissette, for the most part, not present.

"There was a bit of flying blind,” says Chiccarelli, "but Alanis did give me a direction, which was that she liked the electronic elements Guy had brought to the tracks, but wanted me to kick the tracks in the butt. Even when everything is programmed, like with great electronic bands like Justice and Air and Nine Inch Nails, as well as with Guy's work, it's difficult to achieve the dynamics and edge you can get from real players. Guy and Chris had done great stuff and some of the programming was absolutely brilliant, but Alanis in some cases felt that it didn't match the lyrical content of the songs. She also wanted to have more 'humanity' in the tracks. Alanis and I both appeared to have the same thing in mind, which was to keep it modern and keep the programming where appropriate, but also give the arrangements and production more heart and soul. I'm doing a Café Tacuba album at the moment, and because the rhythm section is all machines, to add dynamics I end up putting several different compressors on the drums, turning up one compressor for the verse, another for the bridge, and so on. It doesn't really work to just turn up a drum sample, because you don't get the same feeling. So really Alanis' direction was to bring to the record what a rock band does in live performance.

"With every album you do as a producer, you get a sense of what the artist wants, and it's your job to read between the lines and understand that and deliver their vision. Alanis' initial direction was great, and because she was not around for most of the tracking and mixing, it was great that she gave me a lot of freedom and trusted me to go where I thought it should go. And I would send her rough mixes and she would come back with comments. Another thing that was helpful was working with guys like [drummer] Victor Indrizzo and [guitarist] Dave Levita, who have toured with her, so they understand what she likes and doesn't like. When we were tracking guitars, and I was wondering whether a certain part was too weird for her, it was great to have someone who knows her sensibilities say, 'No, no, she loves that kind of stuff!'”

Songs With Personality

Joe Chiccarelli snapped these camera-phone shots during the tracking at Sunset Sound, showing (above) his drum-mic overhead setup with a pair of Manley Reference Cardioids; and (right) an AEA R88 stereo ribbon mic and the AKG C12 used to record Morissette's vocals.

Joe Chiccarelli snapped these camera-phone shots during the tracking at Sunset Sound, showing (above) his drum-mic overhead setup with a pair of Manley Reference Cardioids; and (right) an AEA R88 stereo ribbon mic and the AKG C12 used to record Morissette's vocals.

As Chiccarelli settled behind Sunset Sound Studio One's unique 64:24:8 API/DeMedio custom desk and pushed up the faders, the directions in which he wanted to take the songs revealed themselves quickly. "One of my goals was to give each song a different personality, while also making sure the album as a whole remained cohesive. I'm a big believer in an album taking the listener to different places. In some cases I decided to totally reinvent the arrangements, in others I kept a lot of what Guy had done. One of the songs I did the least to was the piano ballad 'Havoc', which is a really powerful song. The pianos are mostly Guy's programming, but I heard orchestration on it. I wanted to do something different than strings and horns, and thought of the vulnerable, almost broken sound that woodwinds and clarinets have. So I asked David Campbell, a great arranger that I regularly work with here in LA, to write an arrangement for a sort of woodwind quartet.

"In songs like 'Woman Down' and 'Celebrity', I also kept a fair amount of the programming. They are very angular tracks, and what Guy had done on them was fantastic, so all I did was bring in some live musicians to augment that. 'Celebrity', for example, had an almost Middle Eastern-sounding percussion track. It had a great feel but not quite the impact of a real dumbek player, so Victor layered several dumbek parts with more Middle Eastern rhythms on top. In cases like this, we took Guy's lead and went further, using organic instruments.

"I have to add that it rarely worked to simply replace his programmed parts with 'real' instruments. I recall a case in which I loved the synth-bass part Guy had programmed, and we tried to emulate that with a real bass player, but that didn't work. I had to let the bass player approach the song in his own way, as a real player would. It's the same with the drums. Sometimes I added real drums to complement what Guy had done, in other cases I completely replaced the programmed drums with real drums. In many of the songs, there are three different drum kits, one for the verse, one for the chorus and one for the bridge, just to give different shapes and sizes. In the case of quite a few songs, like 'Empathy' and 'Receive', nothing remained of Guy's arrangements. On some songs, I also asked Alanis to re-sing her lead vocal and/or her backing parts.”

Sunset Overdubs

Chiccarelli began his overdubbing work by recording bass and drums together, mostly in Sunset Sound's Studio One, and then adding individual overdubs, some recorded in Sunset's new Pro Tools suite. "In many cases, I really wanted to experiment with guitar and keyboard sounds and textures, so I'd track bass and drums to the vocal and some element of the programming, and I'd add keyboards and guitars after that. The song 'Guardian' is a more straight-ahead rock song, and in this case Lyle Workman played his guitars at the same time as the bass and drums. We recorded Zac Rae's keyboards at his studio, The Bank, where he has a cool Quad Eight console, and, more importantly, over a hundred vintage keyboards, like Moogs, ARPs, Selinas, Rhodes, Wurlitzers and so on. We went over there to take advantage of all these. Zac is a master of creating distressed sounds and manipulating his extensive collection of funky old analogue stomp-boxes, so we used these as well.

"I recorded Alanis with an AKG C12, which went into the Sunset Sound DeMedio desk preamp, which is similar to the John Hardy preamp, and then a Urei 1176, and then straight into Pro Tools. I used the DeMedio desk preamps for most tracking mics. The electric guitars would have been Royer 121, Coles ribbon mic, Shure SM57 and a Neumann U67 as a room mic. Dave and Lyle were really good at coming up with interesting sounds on their pedals, and I had just bought a set of Chandler stomp-boxes, like the Germanium and Little Devil distortion pedals. We used them, as well as a lot of Eventide pedals, like the Space Pedal and Modulation effects, on bass, guitars and keyboards, and even on vocals. Lyle used a Divided By 13 amp and Dave a Fender Deluxe. Acoustic guitars were recorded with a Sony C37A and at other times a Mojave MA200. I also used the Manley Gold Reference on some acoustic guitars, but the C37A is definitely one of my favourites on acoustics: it's very pretty and sweet-sounding. I mostly used Chandler mic pres on the guitars. Zac's keyboards were mostly recorded via DI, usually heavily effected with pedals, though the Wurlitzer and Rhodes would have been miked with a Shure SM57.

"Sean Hurley played most of the bass parts, and I recorded him on four tracks, with a clean DI track and a DI track with effects. Sean would usually run a tiny bit of sub-octave on the bass, as well as some overdrive or delay, or whatever was appropriate for the song. So I had this extra bass DI track that contained more character. Most bass guitars were played through an Ampeg B15 amp, in some cases a Divided By 13 bass amp. I'd record that with an [Electro-Voice] RE20 on the bass cabinet and a [Neumann] FET 47 in the room, going into a Neve 1073 and probably some Dbx 160 limiters, and then into Tools. Obviously, low frequencies take a while to develop, so I'd place the room mic three to six feet back to capture the wave build-up, and I'd blend that in for some more weight and a more realistic sound. You do have to move these two mics around to find the right spots and make sure you don't get any phasing issues.

"I recorded the woodwinds very naturally, mostly using U67s and with an [AKG] C12A on the flutes, and a FET 47 on the bass clarinet, which has a really nice resonance when you record it up close. The room mic was a stereo Royer SF24, and the balance was probably 60-70 percent room mic and the rest the close mics. Lili Haydn's violin was recorded with a Neumann M49 as an overhead and a mic on her Fender Deluxe, with a little bit of DI mixed in. Drums would have been C12s or Manley Gold References on the drum overheads and vintage Neumann U67s and U47s and Sony C37As.”

A Clean Wall

Joe Chiccarelli took the Sigsworth/Elms Pro Tools sessions as his starting point, adding numerous overdubs and replacement parts. The resulting sessions often ended up being, understandably, rather complex, as shown here by the Edit window from the song 'Woman Down'.

Joe Chiccarelli took the Sigsworth/Elms Pro Tools sessions as his starting point, adding numerous overdubs and replacement parts. The resulting sessions often ended up being, understandably, rather complex, as shown here by the Edit window from the song 'Woman Down'.  Another complex edit window, this time showing the work involved in creating the track 'Celebrity'.

Another complex edit window, this time showing the work involved in creating the track 'Celebrity'.

Unusually, Chiccarelli refused a mixing and engineering credit for Havoc And Bright Lights, saying, "I hate seeing my name on a record more than once. It just looks so egotistical.” (Sigsworth likewise insisted on being credited as a keyboard player and drum programmer rather than co-producer on some tracks, because "with the songs having taken the route that they took, I felt that the fairest thing was to represent me as one of the members of the band.”)

For his mixes, Chiccarelli used the same API/DeMedio desk that had been employed for most of the tracking. "It's a really fat-sounding board, which meant that mixing was, in part, a matter of sculpting holes for things to make sure there was space for everything. Particularly on tracks on which Guy had sent me everything split out, sessions easily added up to 100 tracks and more, so that meant a lot of sculpting! When you mix in the box or on a modern console like an SSL, it's easy to sculpt things — you have your filters and compressors and the sound of the SSL is very detailed — but it's difficult to get things to sound really fat and big. Conversely, when you work on an API or a Neve it's easy to get things to sound big and warm, but it's harder to sculpt details. So during mixing I introduced various plug-ins, even simple EQs by McDSP and Digidesign and Waves, to sculpt the low end, mostly filtering everything below 30Hz and notching out any 200Hz stuff that was getting in the way. Like I said, Alanis likes the wall of sound, which is good, but you don't want a messy, muddy wall. You want to retain clarity and separation and also that impact, and the API/DeMedio desk was great for the latter. It has very powerful and musical EQs that are excellent for boosting frequencies and toughening up the sound. Plug-in EQs are better for sculpting.”

"I always record everything the way I want it to sound, using hardware compression and EQ on the way in — I started in the days of analogue tape, when you got the sounds you wanted, and committed these to tape. I used more outboard during the mixes, like the Retro 176 limiter on the vocal, Chandler Zener and Chandler Germanium compressors on the drums, and so on, and added most of the plug-ins during the mix process, including many Universal Audio plug-ins — I love the UA Satellite card — many McDSP plug-ins on the vocals, the Sound Toys EchoBoy and Crystallizer on background vocals, and other things. But, for the most part, mixing was a matter of riding faders. Alanis is very particular about getting clarity and diction on every single word, so I'd ride up syllables and words to make sure the message was clear. Years ago, I worked with Rickie Lee Jones, who was also fanatical about this, asking me to push up an 'r' in the middle of a word to make the meaning clear! It's great to do these detailed things in the box, but for rock stuff, I really like to get my hands on the faders, to do things like push up guitars in the choruses and build things to create emotion. My first few mix passes are all about doing big moves to build excitement, and after that it's a matter of working on the details.

"Alanis and her manager are, of course, used to hearing finished masters, so I'd pump the level of the rough mixes I sent them. There are a lot of fake mastering plug-ins out there, but to my ears the Sonnox Inflator has the most natural sound and doesn't destroy the mixes. So whenever I have to do a bit of mock-up mastering, I use that plug-in, though I take it off again when I send the final mixes to mastering. The actual mixdown was to analogue tape, with a mix back into Pro Tools for safety. I mixed to an Ampex ATR100 on half-inch ATR tape, at 30ips, +5, no noise reduction. ATR are a boutique company on the East Coast, and they make good tape. It does the tape compression thing and yet the high end does not go all dark. If the artist can afford it, I will always have at least one generation of analogue tape in the mix, because it binds everything together and warms things up. It's a very familiar tone to my ears, and especially in rock stuff, it adds that last little bit of glue that cements the mix.”

The First Take Is The Deepest

Many of the vocal takes on the finished album were from performances that Guy Sigsworth and Chris Elms had recorded at Alanis Morissette's house — with all its attendant distractions. "One thing that I recalled from doing the previous record was that it is really important to capture Alanis' first vocal take,” recalls Sigsworth. "When the ink literally isn't dry yet on the lyrics, she often gives her most emotional performance. I wanted to make sure that we would always be able to record that, and so we had the SE Electronics Reflexion Filter, which I have always loved. Like many people, I even use it in acoustically brilliant rooms to avoid any kind of unwanted reflections around the voice. The filter worked well when she sang softly, but when she sang louder we had reflections coming back into the microphone. Plus Alanis has several dogs that barked at times, so we found a local guy who makes this portable vocal booth, which consisted of four pieces of wood with a door and a window, all kept together with Velcro. That was amazingly useful. We also had an electric and an acoustic guitar in the room, for when we wanted to throw on some guitar, and a generic eight-octave MIDI keyboard for me to play.”

Joe Chiccarelli's experiences of vocal recording were very similar. "She's very quick as a singer. She never does more than a few takes. It's kind of funny, because on a couple of songs I pushed her to do more than two or three takes, and I think she found that a little surprising. She's a pro, she really works from the heart and for her it's all about inspiration, and she goes out there and does what she does. But in a couple of instances I wanted her to do something different for a bridge or so, and while she initially was surprised at my request, when she heard the final vocal she was really happy. So it was worth the collaborative effort. She also loves doing background vocals, and Guy did an amazing job on some of the tracks, piecing together elaborate background vocals. These took a long time to sort out, making some of them more lo-fi sounding and creating doubles and things.”

Another Brick In The Wall Of Sound

Although Alanis Morissette gave Joe Chiccarelli plenty of licence in reworking the album, she also had plenty of input into the process. "Alanis was a great sounding-board during the three to four months that the project took,” he explains. "In response to the rough mixes I sent her, she was always very specific in what she liked and didn't like. She is very particular about her vocals, and would constantly ask me to change a word here and there and make sure the timing and tuning were perfect. One striking thing for me was that she really likes a 'wall of sound' approach to production. If you think of all her albums in the past, they have been very thick-sounding, with many different textures. As I got closer to the end, she kept asking for more. I was more inclined to do something that was a bit rough and band-like sounding, but she kept saying, 'No, no, no, it needs more, more.' Even during mixing, she'd sometimes send me comments back like, 'I don't know whether this section is thick enough,' or 'I don't know whether there are enough textures here,' or 'It needs another counter-melody,' or 'it would be nice if something new was introduced in this section.' So towards the end of the project it was a question of coming up with more layers, adding more guitars, more keyboards, and so on. Sometimes I'd dig up some overdubs that I had scrapped at one point or I'd use more of Guy's original tracking. She was always looking for scene changes. As a producer, you always try to create moments where the listener is engaged again with a new element, and it was important to her that whenever she felt that the action was low, something new was introduced.”

The Sound Of Sample Rates

For his recording sessions, Joe Chiccarelli worked at 96kHz, even though he was using many elements from Guy Sigsworth's original sessions, which had been at 44.1kHz. "I've been working in 24/96 ever since HD came out. The first album I recorded in that resolution was Chris Botti's A Thousand Kisses Deep [2003]. He insisted we did it in 96k and I haven't looked back since. I have no idea why some people are so scared of using it. Perhaps they're also using soft synths and samplers that were based on 44.1 and they don't want to lose their ability to use those instruments. But in 96k there's more air, more clarity, more depth, more separation. For me, it's much easier to mix songs in 96k because of this, especially with sessions that are 100 tracks or more. When you have that many tracks at 44.1 or 48, the mix tends to get all mushy and unclear. At 96k, it's possible to retain a lot more separation. I also think that plug-in processing sounds better at 96k. I look at it as the difference between 15ips and 30ips tape recording. There's more transients and air at 30ips, but some people like 15ips, just like some people like the sound of 44.1. The other thing that was interesting was that during my work on Alanis' album, the studio upgraded from Pro Tools 9 to 10, and the sonic difference was dramatic. Then the studio went to [Pro Tools] 10HDX and again there was a vast sonic improvement!”