Dazzling harmonies, complex arrangements and ambitious production have made multi-instrumentalist Jacob Collier a unique phenomenon.

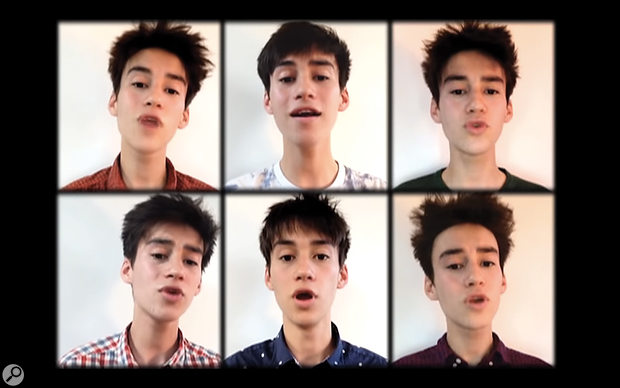

The music industry is currently awash with successful artists who got their break by uploading videos to YouTube, but few have done it with quite such style and panache as Jacob Collier. From 2012 on, the now 24-year-old singer/musician/producer began to earn a growing reputation for his dazzlingly inventive cover versions, multi–part harmonies and split-screen videos in which he could be seen playing an array of different instruments in his small studio at his parents' house in North London. Before long, these videos were going viral and racking up hundreds of thousands of plays.

Eventually, it was his highly creative funk-jazz arrangement of Stevie Wonder's 'Don't You Worry 'Bout A Thing' that struck gold. Featuring a choir of Jacob Colliers performing a cappella before cutting to the musician playing double bass, piano, congas, synth and assorted percussion, it caught the eye of none other than Quincy Jones. The veteran arranger/producer promptly signed Collier to his management agency.

"'Don't You Worry 'Bout A Thing', that was the one," says Collier with a wide smile. "I don't know why. I mean, y'know, for me, I wasn't really concentrating on reaching people, I was concentrating on making the thing as best I could. My technology at that point was very unrefined. I had one [Shure] SM58 and Logic and a MIDI controller. I had my sister's iPad and I had a copy of Final Cut Express. And I had a lot of attention span. I had a lot of imagination.

"So, I would sit down and make these arrangements, and that one just hit a nerve. I mean, it's pretty extremely reharmonised and I think that took a few musicians by surprise. A lot of initial fans were everything from young music students to veterans, y'know. People like Herbie Hancock and Quincy Jones and Take 6 and Pat Metheny. I remember getting these emails in my inbox and just thinking, 'Are you fricking kidding me? Is this really happening?'"

Jacob Collier came to the world's attention with his remarkable interpretation of Stevie Wonder's 'Don't You Worry 'Bout A Thing'.

Jacob Collier came to the world's attention with his remarkable interpretation of Stevie Wonder's 'Don't You Worry 'Bout A Thing'.

Room Modes

Seven years on, Jacob Collier has released three albums — 2016's In My Room, and the first two volumes of his planned Djesse four-album series — and has collaborated with everyone from Laura Mvula to the Metropole Orkest to Take 6 to Steve Vai. He's also received standing ovations the world over for his cutting-edge technological live performances. Collier seems to have taken all of this in his stride and remains so grounded likely because of the fact that he still mainly operates out of his home studio.

"I never fancied I was having a career," he stresses. "I just knew I was learning at the pace I was willing to learn. I was experimenting with the tools I had before me. I was pushing my own knowledge to the end of where it would go and beyond. And the cool thing that I still feel to this day is that that process hasn't changed. It's the same room, it's the same imagination."

True to its title, Jacob Collier's debut album was recorded in his music room at his parents' house, as were the YouTube videos that made him a star.

True to its title, Jacob Collier's debut album was recorded in his music room at his parents' house, as were the YouTube videos that made him a star.

Under Canvas

The room that was to become Jacob Collier's studio at his parents' house has, in one form or another, been the family's designated music room for his whole life. "Literally 24 years, which is the length of my life thus far!" he laughs. "I've always lived in the same house, which I feel really lucky about. So, that was the room where the piano lived and I would spend a lot of time there just messing around with chords."

Further sparking Collier's imagination as a kid was the fact that his violin tutor mother taught her students in that room. "I would sit on her lap," he remembers, "and watch her and listen to her teaching and sort of began to get the themes of music in my head. She'd be playing everything from Bach to Beck to Prince to Bartok. Folk music, rock music. So, I didn't see any reason to exclude different styles from others. I just sort of absorbed the whole thing."

Collier started dabbling with making music on computers, using Cubase, at the age of only seven. By the time he was 11, he'd moved onto Logic. "By the time that came along, I knew I'd found my home and I've been using Logic therefore for 13 years, so just over half my life. Being in that room is so much about the software and I would say that Logic is very, very much a primary canvas. Almost a primary instrument for me, in the sense that if I think about a sound, I tend to be able to achieve the vague sound that I'm going for using those tools, simply because I've been spending so many years working with that skill set and working towards strengthening different kinds of sounds.

"Y'know, I remember the time that a compressor just meant gain," he adds with a grin. "It was like, 'A compressor makes things louder!' And then you realise that, oh no, actually what you're doing is you're compressing a sound. The same was true for reverb. I thought it was just, like, wet and dry. But then you can tweak things. Through my teens I started to experiment with a variety of different things and realised that there's so many things you can do with sound."

Magical Mystery Busses

As accomplished as he is as a multi–instrumentalist, Collier's chief passion was sound. He has, of course, grown up in an age where he didn't ever know anything other than the seemingly endless possibilities of digital home recording.

"I dipped my toe into musical education for a little bit," he says, "and people talk about harmony and rhythm and melody. But sound was this mysterious thing that just happened on its own, so it was super cool to learn those skills first-hand. First of all, it was like, I want to record piano, bass and drums and I want to play all the instruments. Then you realise, well, I want the piano to sound a bit further away, or a bit closer. And so, you start playing with microphone placement, you start playing with reverbs, you start playing with compressors. You start playing with busses. I remember busses were such a mystery for a long time.

"But it's incredible, I think, to have grown up in an era where that was as much part of the music process of learning and experimenting as playing instruments. So, the studio was an instrument and still is now."

Crazy Harmony

Even before he made his first album, Jacob Collier had already made his name as a pioneering live performer. Quincy Jones's first offer to the young musician was a huge opportunity: the chance to open for Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea at the Montreux Jazz Festival. Coincidentally, at the same time, Ben Bloomberg, a PhD student at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) got in touch wondering if Collier would like to collaborate on a stage show.

"He said, 'I work with Imogen Heap, Bjork, OK Go,'" Collier recalls. "'I make crazy stuff and have you ever considered making crazy stuff?' I wrote him back saying, 'Well, funny you should say that because, yes, I have considered that. I have this gig and maybe we can build something for it?' So, we got on Skype and we spoke through all the different options and the first thing we wanted to build was the vocal harmoniser."

Collier had a desire to create a MIDI–triggered stage harmoniser that was more ambitious than anything on the market. For a start, he'd been frustrated that most were only four-note polyphonic. "I wanted 12 and I wouldn't settle for anything less!" he laughs.

Collier had a desire to create a MIDI–triggered stage harmoniser that was more ambitious than anything on the market. For a start, he'd been frustrated that most were only four-note polyphonic. "I wanted 12 and I wouldn't settle for anything less!" he laughs. "Ben and I sat down and we looked at everything that was on the market. We began to combine sounds where we liked them, and then we would stick with something and begin to modify it to our liking. So, 'We like this, but it needs to be panned in a more sporadic way.' Or, 'We like this, but it needs to have some Mid/Sides compression, so it grows and expands when it gets louder.' Or, 'We need this so that it has portamento values to each note.'

"What I realised is, as a piano player, I wanted to be able to be fluid and improvise, and so the cool thing was realising that there was a way to do it that felt like I was playing a human voice, so it wasn't so far removed. It didn't sound like a vocoder, for example, or a talkbox. It sounded like a harmoniser in the sense that it was a sampler. It samples my voice but it has a very distinctive sound of its own, which I've really fallen in love with. So, for example, beatboxing, you're playing a huge great vocal synthesizer drum machine. Then, over the course of time, we developed the freeze pedal, so I can play a chord, sing, freeze it like a piano and then I can modify that sound. So, I can pitch-bend it, and add a bunch of SoundToys plug-ins over the top to make decoration."

The resulting custom harmoniser, housed in a cast aluminium case, is a mixture of hardware and software. "It's hardware in the sense that there's the modified circuit board of something which originally was made by TC-Helicon," says Collier. "And then there's the software: essentially three iterations of Antares' Harmony Engine run simultaneously but compressed together, mixing them around, treating them as synthesizers. It's an amazing beast.

"Playing it is a little harder than it looks, actually," he adds. "You have to know what note you're singing at all times. You hear the note that you're singing in addition to the notes that are played. I can go 'Eee' and I can see an E Major chord. I don't have to work out what the note 'E' is beforehand. And those kind of things I don't think I really thought about. At first it was really hard. But at this point, it almost sort of feels like part of my DNA."

Invisible Loops

Along with the harmoniser, Bloomberg and Collier created an elaborate one-man show, based around a system of loopers. "Six looping machines all run through Ableton," Collier explains. "All controlled via MIDI messages in a timeline. Ben and I realised early on in the process that the important thing about this one-man show with all these instruments, all these loopers, is that it didn't come across as a gimmick, y'know. So, all the looping stuff is completely invisible. The laptop's off stage, even. And so, it just runs via USB extenders and, essentially, I hit 'go' on my [Novation] Launchpad, I have a click in my ears, the timeline runs and I've memorised every loop. There's different stations for percussion, drums, bass, vocals, harmoniser, keys and miscellaneous.

To reproduce his complex arrangements live, Jacob Collier records and triggers loops using multiple Novation controllers.Photo: Chris Mayes-Wright

To reproduce his complex arrangements live, Jacob Collier records and triggers loops using multiple Novation controllers.Photo: Chris Mayes-Wright

"All I have to do is walk up to an instrument, play it for four bars, walk away from it, and it keeps playing. And the amazing thing was that we had these visuals behind. We had two connected 3D cameras which can track my skeleton onstage, and so when I would make a loop, you'd see me on the bass and then you'd see me walk away from the bass and I would keep playing the bass on the screen onstage. You would build a group of four or five loops and you'd see four or five Jacobs in 3D space on the screen, playing those loops."That kind of system started off being a thing where I'd be thinking, 'Oh, how can I remember all of this?' And then once I'd remembered it, it was just this musical experience where I would be improvising every instrument every night, working with those parameters, involving the audience to sing parts, all sorts of things."

Multi-instrumentalist Jacob Collier performing live.Photo: Matthew Tucciarone

Multi-instrumentalist Jacob Collier performing live.Photo: Matthew Tucciarone

Tracks Upon Tracks

In the wake of the Montreux Jazz Festival gig for which it was created, Jacob Collier toured his one-man show the world over in support of his debut album, In My Room. In stark contrast to his live setup, his recording approach was at this stage far less elaborate, involving Logic, a Focusrite Scarlett 18i20 interface and, in the modest microphone department, a C12VR, a pair of C414s and a D12 (for bass drum), all from AKG.

"No preamps, no nothing," Collier points out. "Just me and Logic. And it sounds like that. It has a particular vibe of being just the sound of the room. There's no clever stuff. It's just like I basically record acoustic sounds and then work with them in Logic, but I don't tend to mess around with them. I don't add a ton of plug-ins and stuff."

Jacob Collier: I've done something which is 200 tracks, multi instruments, on one SM58 and it sounds good. It sounds like the idea that I had, and that's what I always aim for.

In fact, making In My Room, Collier tended to just use native Logic plug-ins to process his sounds. "Mostly," he nods. "I mean, since then I've found some amazing plug-ins. But I'm a firm believer in the idea that you don't need some crazy stuff to make good music. I mean, I've done something which is 200 tracks, multi instruments, on one SM58 and it sounds good. It sounds like the idea that I had, and that's what I always aim for. So, those sort of snobs who say that I haven't got quite the right hardware, I haven't got quite the right preamp on my vocal, or I just need the right reverb, it's like, you work with what you have. And I've always believed in that."

When it comes to Logic, a quick view of Jacob Collier using the software on YouTube during one of his live streams proves him to be something of a whizz. There's also no denying exactly where he stands on the ongoing Logic versus Pro Tools debate.

"The thing about Logic which I love is that you can make your own keyboard shortcuts, and that's why I'm so anti-Pro Tools," he says. "Logic has just upped the track limit to 1000 and I was so happy, because I've been slamming up against that 256 limit for so many years. Almost every song on the album is over 256 tracks and I have to bounce things down. I like leaving the tracks there without bouncing them down, so there are more options for panning and bussing. So, now I can go up to 1000, which is so satisfying to me."

Creative Tools

Since signing to Decca Records and embarking on the Djesse four-album project in 2018, Jacob Collier's studio has undergone something of a revamp — even if he didn't want it to be a major one. "I got a soundproofed door and soundproofed window," he explains, "with some audio treatment panels up on the wall. But nothing crazy. I mean, the room is the same room. It's just that there's a little more space. I built some storage up the top so there's more floor space now. Y'know, small things just to get the sound quality a little tighter and to give myself more options."

Djesse Vol 2 album cover. Original image created by artist Astrig Akseralian.Collier's main vocal microphone these days is a Neumann U87, with his pair of C414s replaced by Mojaves. "Two Earthworks mics over the drums, two Earthworks mics inside the piano," he explains, "and two room mics that were built by Brian at MIT. I've got some amazing Avedis and Grace preamps and I got new Kii Three monitors, which are just unbelievable, so special. There are six drivers on every speaker, four on the front and two on the back. There's no subs, but it sounds huge."

Djesse Vol 2 album cover. Original image created by artist Astrig Akseralian.Collier's main vocal microphone these days is a Neumann U87, with his pair of C414s replaced by Mojaves. "Two Earthworks mics over the drums, two Earthworks mics inside the piano," he explains, "and two room mics that were built by Brian at MIT. I've got some amazing Avedis and Grace preamps and I got new Kii Three monitors, which are just unbelievable, so special. There are six drivers on every speaker, four on the front and two on the back. There's no subs, but it sounds huge."

On the Djesse albums, Collier has also explored a number of new plug-ins, with Audio Ease's Altiverb reverb, the SoundToys and Waves collections, XLN Audio's RC-20 Retro Color tape emulator and iZotope's RX7 restoration package among his current faves. "iZotope RX is just extraordinary," he enthuses. "I've sought out a plug-in that can do that, in that way, for many years. I needed that so desperately, for when you record orchestra or choirs. If you've got room mics and you want to get rid of a note or a squeak, then you can go in and do that."

If there's one plug-in that has excited Jacob Collier most recently, it's Xfer's LFO Tool. "It's a bit like [Waves] OneKnob Pumper, that just goes, like, 'NaH-naH-naH'," he laughs. "LFO Tool's the same, but you can draw your own curve and that means you can draw all sorts of different side-chain compression curves. You can input up to 16 divisions per division of dynamic range, and that's really exciting for someone like me who thinks very musically about sound.

If there's one plug-in that has excited Jacob Collier most recently, it's Xfer's LFO Tool: "You can draw all sorts of different side-chain compression curves. You can input up to 16 divisions per division of dynamic range, and that's really exciting for someone like me who thinks very musically about sound."

"It's like, I don't just want something that makes it sound more compressed or makes it sound more high-end or something. I want something that is going to give me more ideas. So, something like LFO Tool gives me ideas. The music will take a turn as I'm flicking through presets and it's like, 'Aw, I would never expect that sound.' I like plug-ins that take me by surprise."

In the groove department, meanwhile, Jacob Collier is no great fan of quantising his parts. "Grooves around the world, like samba, it's not quantised," he stresses. "All the stuff that swings the hardest. Computers have the wrong idea. Y'know, some quantised music sounds good, like techno. But some of the most gorgeous grooves are wonky, and so I've just become obsessed with moving things so that they have exactly the right amount of wonk. I want to lean towards this beat, and the computer won't help you there, 'cause a computer is so rigid. So, I have to bring the human element to that process by allowing the thing to be wonky."

Lack Of Logic

The making of the Djesse albums involved Jacob Collier stepping out of his home studio, collaborating with different artists and recording in such far-flung locations as the US (New York, Los Angeles, Nashville), Holland, Morocco and Japan.

"I think the transition has been easy enough," he reckons. "It's challenging creatively to jump between all these different ways of working. If I compare and contrast working with Steve Vai to working with Sam Amidon I mean, Sam Amidon is a folk fiddler and singer, Steve Vai is a rock guitar legend. They both have completely different schools of thought, but they have things in common. So, my job is to find the common ground, extract it from them, and build my project."

Among his favourite studios were Abbey Road Studio 2 and Ocean Way in LA. "I tend to rely a lot on automation in post," he says, "and so I don't tend to touch the desks. Sometimes the engineers, if they know the musicians really well, for example with an orchestra, they'll touch things on the desk and then they'll print the desk mix out. But, in general, I work with the tracks from scratch when I put them into Logic."

One of the frustrations for Collier, though, was that very few professional studios use Logic. "Hardly any do," he sighs. "All have Pro Tools. It's very annoying, so I had to buy Pro Tools. Bad news. And then I had to learn how to consolidate tracks, bounce in place, export, delete all the silence so I can see where everything is. And at that point I will jump into Logic and begin work.

"Basically, you completely start from scratch at that moment. But I like building from the ground up. I've never been the guy to jump on the desk and automate on the desk. I think if I was brought up as a sound guy or someone who was used to that, I would've gravitated towards that. But when I was a kid, the way I visualised dynamics was click and drag, and so that's what I'm used to.

"Also, for me, a lot of the dynamics come as I play. If I myself am recording something, I'm gonna make sure that there's enough life in the recording, so that I don't need to do a lot in post. I don't want to over-automate anything. I just wanna make sure that I bring out the essence of whatever that recording is in the best possible way I can and not try to be too clever with that."

No Looking Back

It's clearly an exciting time for Jacob Collier, with Vol. 3 of Djesse to be released early in 2020 and Vol. 4 to follow later in the year. The 24-year old is bursting with enthusiasm for the future. "Wait 'til you hear them," he says of the upcoming albums. "There's some crazy musicians. I'm really excited about Volumes 3 and 4 and I'm thrilled that 1 and 2 are out. This whole journey is beginning to take wings."

information

Epic Harmony

The #IHarmU project featured stars such as Herbie Hancock as well as members of the public.An interesting creative diversion for Jacob Collier amid all of this productivity has been his #IHarmU crowdfunding campaign. For $100 donations, he invited musicians and the public to send him 15-second clips of their singing, which he would then develop vocal arrangements around using his multitracked harmonies. The results were then uploaded onto YouTube in his trademark split-screen videos. Artists who stepped forward included Jamie Cullum, Herbie Hancock and Ben Folds, though the public contributions were the toughest to handle.

The #IHarmU project featured stars such as Herbie Hancock as well as members of the public.An interesting creative diversion for Jacob Collier amid all of this productivity has been his #IHarmU crowdfunding campaign. For $100 donations, he invited musicians and the public to send him 15-second clips of their singing, which he would then develop vocal arrangements around using his multitracked harmonies. The results were then uploaded onto YouTube in his trademark split-screen videos. Artists who stepped forward included Jamie Cullum, Herbie Hancock and Ben Folds, though the public contributions were the toughest to handle.

"The challenging ones were some of the people who weren't used to singing, or maybe had never sung before," he says. "But the rule was, I can't pitch them. So, I didn't pitch anybody. If they go between semitones, I go with them. I modulate microtonally to fit to their needs. The hardest one to date was a three-year old and she sang 'Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star' and it was completely, utterly random notes. Not just like notes on the piano, but between notes, and it was so hard. I was like, 'How can I not change her?'

"I figured it out, because there was always a way. But you have to make that person sound as contextualised and beautiful as possible without changing them. Conceptually that felt like the correct approach, rather than being like, Yeah, OK, Auto‑Tune, then I can harmonise normally. It's like, y'know, if you're gonna drift up in pitch throughout, I'm going with you."

One of the standout tracks from 2019's Djesse Vol. 2 took this approach and ran with it. Collier's arrangement of Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer's 'Moon River' featured 150 voices, including those of Collier's fellow artists, friends and family.

"I asked everybody to send me a 'Moon' video on their phone," he explains. "I asked them to send me a note in Bb major. Some of them nailed it, some of them didn't, so I would round them to the nearest note. I dropped them into Logic, I tuned them up and I drenched them all in an Altiverb reverb preset from the Notre Dame [Cathedral] because I did it on the day the Notre Dame fire happened. So, the first minute of 'Moon River' is 150 of my favourite musicians and people around the world singing an epic cluster chord in the Notre Dame."

Collier did tune these particular vocal contributions, but did so manually and insists that he doesn't ever use Auto‑Tune or even Logic's Flex Pitch. "No, I hate Flex, because it leaves artifacts," he says. "I use one of the most archaic parts of Logic that no one ever uses, which is called Time And Pitch Machine. You can put the number of cents in that you want to change, and it speeds up or slows down the audio file.

"I did this with my own recording and my own arranging. If I sing a melody and there's a note that's, say, 13 cents sharp, I'll hear that and I'll say, OK, minus 13, enter, and that note will go down. But it won't leave any weird artifacts because it's destructively slowing down the audio file. So, yeah, with 'Moon River' it was kind of fine-tuning. I'd listen to the note and be like, 'That's about 60 cents sharp, so minus 60.' Panned everyone equally and then you've got this massive great big omnichord.

"But I love those kinds of challenges, y'know. And obviously iPhones have a bunch of hiss and artifacts and there was a bunch of noise, so I relied pretty heavily on RX for that. I'll go and clean up the audio files, drop them back into Logic. Then, it was just one of those things where if you put reverb on it, it just sounds huge, sort of almost otherworldly."