The Genelec factory in Iisalmi, Finland. Long days in Summer mean that the solar panels can provide a good proportion of the company’s energy needs; at other times, green energy is purchased from local sources.

The Genelec factory in Iisalmi, Finland. Long days in Summer mean that the solar panels can provide a good proportion of the company’s energy needs; at other times, green energy is purchased from local sources.

What can audio equipment manufacturers do to minimise their impact on the environment? We look for answers in the forests of Finland.

The audio industry is a small one compared with aviation, fashion or consumer electronics, but it still leaves its mark on the planet. From microphones to mixing consoles, every product we buy has an environmental footprint.

Last year’s COP26 summit made clear that urgent action is needed to mitigate our impact, and with governments increasingly committed to ‘net zero’, targets are likely to be forced on everyone sooner or later. However, there are already forward‑looking manufacturers who see sustainability as more than just a regulatory hurdle to be overcome. In this short series I’ll be meeting some of the companies who are innovating to make the audio industry greener.

Northern Lights

If you want to know what can be done to make audio equipment manufacturing more sustainable, a good place to start is Iisalmi. For the last four decades, this small town in central Finland has been home to one of the world’s best‑known studio monitor brands. And what we now call ‘sustainability’ has been part of Genelec’s philosophy since before it became a buzzword.

...what we now call ‘sustainability’ has been part of Genelec’s philosophy since before it became a buzzword.

This ethos has produced many tangible results. For example, Genelec and their partners spent many years developing the recycleable composite ForMi material used for the M‑series monitors, while nearly all current models use cases made from recycled aluminium. The entire factory is powered from renewable energy sources, including solar panels, and the company has a policy of sourcing everything from local suppliers where possible. In 2021, 60 percent of factory waste was recycled, and the stated goal is to raise that figure to 65 percent in 2022.

Siamäk Naghian is Genelec’s managing director.But what’s apparent from talking to the company’s managing director Siamäk Naghian is that visible achievements of this sort are not arrived at in isolation. They grow organically out of a deeper company culture and, to some extent, from the values of Finnish society. Real progress on sustainability can’t be made only by thinking of it as a potential marketing tool or box to be ticked. It has to be present in discussions and decisions at all levels. “There are many companies who are saying that they have zero footprint, and I think that in some cases that’s misleading,” says Siamäk. “You can very easily say that you have zero footprint by planting forests and doing other things that compensate, but I don’t think that is the way to get to zero footprint. The primary way is that you have to minimise your footprint in terms of what you spend, in terms of material and energy.”

Siamäk Naghian is Genelec’s managing director.But what’s apparent from talking to the company’s managing director Siamäk Naghian is that visible achievements of this sort are not arrived at in isolation. They grow organically out of a deeper company culture and, to some extent, from the values of Finnish society. Real progress on sustainability can’t be made only by thinking of it as a potential marketing tool or box to be ticked. It has to be present in discussions and decisions at all levels. “There are many companies who are saying that they have zero footprint, and I think that in some cases that’s misleading,” says Siamäk. “You can very easily say that you have zero footprint by planting forests and doing other things that compensate, but I don’t think that is the way to get to zero footprint. The primary way is that you have to minimise your footprint in terms of what you spend, in terms of material and energy.”

Data Driven

Siamäk emphasises that the most important tool in reducing that footprint is information. The more Genelec know about their own manufacturing processes, those of their suppliers, and the ways in which their products are being used, the more effectively they can address their environmental impact.

As production director Piia‑Riitta Bergman puts it: “Traceability is not only about maintaining quality, but making sure that we can understand the product later on. So, for instance, we can keep track of the sub‑assembly parts, such as the PCBs that we produce ourselves. They are individually marked and tested on the individual, sub‑assembly level. And then once we make the product itself, we have different information about the products in our production databases: for instance, who’s done the assembly, when it’s been done, then the test result itself, it’s all stored in the database. And if somebody asks later, or if there is a customer request or any question afterwards, we trace that data that we have from the factory.”

Production director Piia‑Riitta Bergman.Some of the uses of this data are obvious. Consistency of manufacture is vital in many industries, and especially so for a business like Genelec whose products are expected to perform to demanding standards for many years. The detailed internal record‑keeping process helps them optimise their manufacturing process to improve consistency and minimise the number of rejects. “We measure the first‑pass yield in all those testing phases that we have,” explains Piia, “If we have a high yield, it means there are not so many components wasted, or speakers that have to be repaired at the factory.”

Production director Piia‑Riitta Bergman.Some of the uses of this data are obvious. Consistency of manufacture is vital in many industries, and especially so for a business like Genelec whose products are expected to perform to demanding standards for many years. The detailed internal record‑keeping process helps them optimise their manufacturing process to improve consistency and minimise the number of rejects. “We measure the first‑pass yield in all those testing phases that we have,” explains Piia, “If we have a high yield, it means there are not so many components wasted, or speakers that have to be repaired at the factory.”

On other occasions, though, analysis of the data can lead to surprising conclusions. For example, it might seem obvious that the main environmental impact or footprint of a studio monitor lies in materials, manufacturing and shipping, but that may well not be the case in practice. Active studio monitors are designed to be used continuously for long periods of time, and Genelec’s research suggests that as much as 90 percent of the lifetime environmental impact of a monitor speaker can be down to energy consumption from normal use. Obviously, that can be addressed by consumer choices such as buying green electricity for the studio, but it also feeds back into design considerations. Genelec were therefore early adopters of power‑saving management and Class‑D amplifiers, in part because of their far greater efficiency.

Similar considerations crop up at every stage of the design and production process. For example, it’s self‑evident that a product with a long working life is preferable to one that breaks down quickly. But achieving that goal may mean striking a balance between considerations that tend to work against one another. A design that is more easily repairable and upgradeable might be more prone to go wrong in the first place. A product that takes more material and energy to make might be more robust than one that has a smaller initial footprint. Training local service engineers and maintaining stocks of spare parts in all territories will impact the environment in different ways from a more centralised approach, but how do you judge which is better?

“If we are going to offer servicing for the long term, then a basic question is: who will be doing it?” says Siamäk. “Is it our distributors who will be doing that, or the dealers, or other external partners?”

Genelec still service and maintain legacy products even as far back as their very first loudspeaker, the S30, which was launched in 1978.“That thinking begins in the design phase of a product,” adds Piia. “I’ve been involved sometimes in R&D projects and the mindset of design for serviceability has been built in from the start: what are the effective and best ways to repair and service the products?“

Genelec still service and maintain legacy products even as far back as their very first loudspeaker, the S30, which was launched in 1978.“That thinking begins in the design phase of a product,” adds Piia. “I’ve been involved sometimes in R&D projects and the mindset of design for serviceability has been built in from the start: what are the effective and best ways to repair and service the products?“

The Dash To Digital

Another challenge concerns the increasingly important role played by digital signal processing in Genelec products. On the plus side, this permits the implementation of technologies such as intelligent signal sensing, which can reduce idle power consumption. But on the down side, the pace of change is much higher. We’ve all had the experience of finding otherwise functional products rendered useless because digital components have become unsupported or obsolete. How are Genelec ensuring that their digital products will have a long working life?

“Now, to a large extent, we are part of other industries like IT and telecoms that have a different lifecycle in terms of components,” admits Siamäk, “but I think there are a few items there that you can also consider. Number one is that even in that industry, there is a difference between quality of components. So you can always think about what is the best choice. When you are targeting long‑term product lifetime, it really matters what kind of component you use. Another thing is what kind of design you make and how you optimise your design, in the sense of how modular you can make it — because you can keep updating the digital part, but you don’t need to update the whole design. And that, essentially, is connected to the company model. What kind of competencies do you have? What kind of visibility do you have in what you do, and what kind of skills do your people have?”

Genelec’s emphasis on modularity and visibility brought unexpected benefits two years ago. “During Covid we faced a situation that I think was very common for the whole industry. Suddenly, because of the factory fire in Japan, AKM could not supply converters. Many companies who didn’t have visibility in their design couldn’t adapt to that, but we had the possibility to redesign and replace the components.”

Siamäk also suggests that the frenetic change we’ve seen in digital hardware over the last 30 years may not be a permanent state of affairs. As hardware processors become more powerful and more open‑ended, there is more scope for improving products through software updates rather than by replacing chips. “In the short term, the cycle time is very fast, but it is always like that in the beginning. It develops, and things are changing in the digital world. If you compare, for example, a processor that you bought 10 or 15 years ago with one that you can now buy, the division between the hardware and software has changed. You can do a lot more with the software.”

Looking Upstream

A company like Genelec also depends on numerous suppliers, from the renewable energy provider whose product powers the factory to sources of wood pulp, plastics, metals and electronic components. Here, again, information is crucial. Genelec can properly understand their own environmental footprint only by auditing those of their suppliers too. “Over the last 20 years, supply networks have been going further,” says Siamäk. “When you have everything close to you, of course, you have good visibility over what’s going on. You can also do a lot together. But if you have, for example, suppliers in the Far East, you don’t always have enough visibility, especially when you go to the next tier, for those suppliers who don’t only supply the audio industry.

“For example, a certain material may go to lots of different industries, and then you don’t have the possibility to see and to go deeper. And I think that is one of the biggest issues. To understand the footprint, you need to know what kind of data you would need, and it is not always easy to get that, because the supply network is far away. Especially when you go to the electronics side, some of those components that you may think that you are buying from European companies actually come from the Far East. And of course that’s a challenge for everyone. But we have a principle that for critical components, we try to obtain them from suppliers within 200 kilometres, if there is any possibility.

...we have a principle that for critical components, we try to obtain them from suppliers within 200 kilometres, if there is any possibility.

“Always, of course, you have to also take care that what you do is competitive. At the same time you have to take care of quality. At the same time you have to take care that what you offer will be relevant to people also in terms of price. That, again, is a matter of what kind of compromise you would like to make. We know that if we buy parts from even Estonia, it will be cheaper, but still, we prefer to use suppliers with whom we can work for a long, long time together, because that is also one way to optimise the cost. You focus on quality and long‑term relations.”

Shaping Shipping

Electronics is one area where Genelec have to interact with much larger global business. Another is logistics. Some aspects of this are fully within their control; for example, they’ve put considerable effort into minimising the amount of packaging they use, and into ensuring that materials are recycleable or biodegradeable. Even this is a bigger challenge than it sounds, as materials that are considered acceptable in some territories cannot be recycled or composted in others. But when loudspeakers leave the factory, they enter a world of global shipping over which a company like Genelec can have little influence.

“There’s certain areas where you can do a lot, because it is up to you and the choices you make,” explains Siamäk. “But there are certain areas where you have fewer options. And I think logistics is one of those areas. It depends on where your customers are. It depends on where your supplier networks are. And it depends on what kind of logistics services you have the possibility to use. And then when you look at logistics as a global business, basically it is optimised for somebody else than us. That is the starting point. And now you have to find what the options are that you have, and how you can optimise them for your operation.

“For example, you look at how you design your packaging and how much space you use for that — but also what kind of product batches you choose, what kind of inventory you choose to have. These are the things that you can consider when you look at how to optimise that.”

Piia continues: “What do you have in your inventory? Is it components? Or is it semi‑fitted goods, or is it products? And where are the inventories? What about our daughter companies, what kind of inventories do they have of the products? How do we logistically deliver products to them? We’ve done a lot of study about that lately to find out what are the most effective ways.”

“You have to have logistics, because otherwise you cannot deliver,” concludes Siamäk. “But I think that is one of the biggest items when you look at sustainability as we go forward, also, because the network that you have is global. You are not a global company just because you have customers who are here and around the world, but also because of the operational system.”

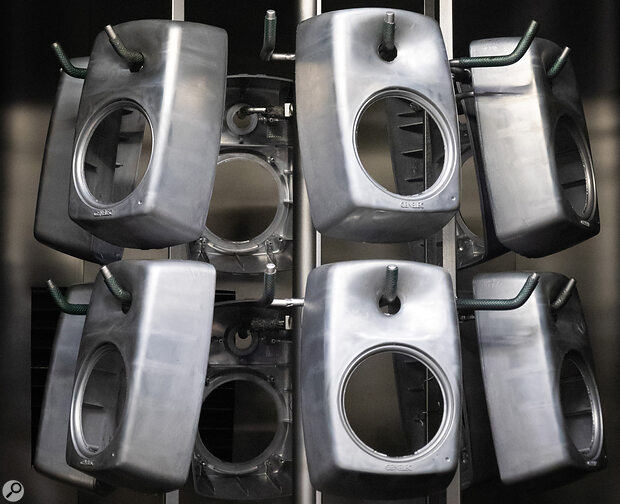

For a number of years, most Genelec monitors have been built using recycled aluminium. Recently, they have started to offer a ‘raw’ finish as an option to customers; cutting out the usual powder‑coating and painting processes reduces the environmental impact significantly.

For a number of years, most Genelec monitors have been built using recycled aluminium. Recently, they have started to offer a ‘raw’ finish as an option to customers; cutting out the usual powder‑coating and painting processes reduces the environmental impact significantly.

Sharing Sustainability

Once assembled, every Genelec monitor is individually tested for performance (top) and electrical safety. This data is all stored alongside serial numbers and details of all the parts it contains, enabling a very high level of traceability.

Once assembled, every Genelec monitor is individually tested for performance (top) and electrical safety. This data is all stored alongside serial numbers and details of all the parts it contains, enabling a very high level of traceability. There is no point in producing something that is greener than competing products unless people actually choose your product over theirs, and as Siamäk says, sustainability in itself hasn’t always been a selling point. “When we developed the M series, we did about 10 years’ work with the universities to come up with the composite material that was 50 percent wood and 50 percent recycled plastic. But we realised that it was very difficult actually to use that as a value proposition when we communicated with people. In markets like the US, direct feedback was: ‘In audio, who cares?’”

There is no point in producing something that is greener than competing products unless people actually choose your product over theirs, and as Siamäk says, sustainability in itself hasn’t always been a selling point. “When we developed the M series, we did about 10 years’ work with the universities to come up with the composite material that was 50 percent wood and 50 percent recycled plastic. But we realised that it was very difficult actually to use that as a value proposition when we communicated with people. In markets like the US, direct feedback was: ‘In audio, who cares?’”

Thankfully, attitudes have changed in the decade or so since the M series was introduced. “Ten years is not a long time, and now, I think everybody will at least receive your message when you talk about sustainability. So that is a big change. And, of course, that is in favour of what we have been doing.”

Now that sustainability is a “value proposition”, though, a different question arises. The best thing for the industry and the planet would be for Genelec to share their hard‑won experience and knowledge with other companies who haven’t made the same investment in sustainable manufacturing. But wouldn’t this in effect be giving up a competitive advantage? Siamäk doesn’t see it that way.

“I worked at Nokia during the time that the mobile phone system was developing. And I think one of the most important things those companies did was standardisation. And that was a huge job. In the ’90s, the number one competitor we had was Ericsson — Nokia from Finland, Ericsson from Sweden, and we have this traditional competition — but we were sitting in the same working group, making the standard for the air interface for the mobile system. So it was a shared mission and everybody understood: OK, if you do that, then it’ll be good for everyone. People will adopt the technology because it’ll be an open interface and everybody can contribute. And that was exactly the same situation. If you cooperate with partners, even competitors, in developing certain technology, that can actually serve everyone. If we can create that kind of network in our industry, it would be good for everyone. I don’t think that’s a negative thing or that it’s taking away from your competitive advantage, because at the end of the day, I think you always have the option to make it better.

Siamäk Naghian: If you choose the right thing, the extra work that you do for sustainability is not in conflict with your business.

“If you choose the right thing, the extra work that you do for sustainability is not in conflict with your business,” concludes Siamäk. “We are not actually spending more money for doing something extra. It is an integrated part of what we do. For example, if you optimise the logistics, it actually benefits both sustainability and your business as well. Personally, I think that’s the most interesting part of the whole thing: how you can come up with solutions that could serve both. We are talking about a company with more than four decades of being deeply involved in this kind of work, as part of its philosophy.

“At the same time, we know that the amount of work that we still have to do is huge. I mean, the most optimised situation of all would be that we wouldn’t build a single product!”

If you've enjoyed this article, listen to our SOS Podcast on Genelec's active monitor development.

People & The Planet

Genelec’s approach to sustainability is integrated into every aspect of the company’s operation, including human resources. It’s important that employees share this ethos; and in a relatively small community with few other large employers, it’s vital that Genelec invest in their staff. “Sustainability is so much connected to the values that people have, and the mindset that people have,” says Siamäk Naghian. “It stems from there.”

“Recently, I’ve been thinking about social responsibility, for instance towards the people that work at the factory,” says Piia‑Riitta Bergman. “How do we work together? How do we train people? What sort of long‑term plans do we have for them? We have people that have been working for the company for a very long time. I see it as a part of sustainability to find a sustainable way of working with people. What kind of an actor are we in this society where we live, as a company?”