Familiarity with a few common articulations is the key to successful MIDI string arranging.

This series is designed to give you an overview of all the instruments in the orchestra, from the tiny piccolo to the towering contrabass clarinet. Before moving on to woodwind, brass and percussion, though, I’d like to spend a little more time with the strings, as their extensive array of playing styles so often provides the heart of an orchestral arrangement.

The ‘String Playing Styles’ box lists the performance styles (or ‘articulations’) commonly included in today’s string sample libraries. Don’t be put off by the classical-sounding Italian names: it’s not obligatory to use them all in an arrangement, and you’ll probably find that only a handful of them are relevant to your music. Once you’ve identified those essential styles, you’ll be one step closer to creating effective string parts. In any case, the fact that we’re using samples rather than hiring the London Philharmonic Orchestra gives us plenty of time to experiment, and anything that doesn’t sound right can be fixed without incurring any cost!

To get started on a MIDI string arrangement, I suggest you concentrate on a few basic styles, the most important of which are legato, sustain, spiccato, pizzicato and tremolo. As explained in last month’s article, today’s legato patches incorporate real-life transitions for every note on the instrument up to an octave in either direction, so when you play (say) a note of C4 followed by an E4, you’ll hear a sample of that particular major third interval. In order to cover every possible interval, legato patches use a ton of samples, so those with less powerful systems may find it expedient to use sustains rather than legatos while sketching initial musical ideas.

Keyswitch Setups

Diagram 1: A five-way Vienna Instruments keyswitch matrix containing (L-R) legato, sustain, spiccato (the currently selected style), pizzicato and tremolo violin section articulations.Faced with the headache of keeping track of multiple playing styles across dozens of instruments, many composers opt to use a dedicated patch for each articulation. While that keeps things simple, it tends to generate a huge track count when applied to the entire orchestra, in a worst case leading to repetitive strain injury as you repeatedly scroll up and down the screen trying to locate those pesky pizzicato violas. An alternative, screen-real-estate-saving method is to use the custom keyswitching facilities supplied by some companies to create all-in-one keyswitch patches for your most commonly used articulations.

Diagram 1: A five-way Vienna Instruments keyswitch matrix containing (L-R) legato, sustain, spiccato (the currently selected style), pizzicato and tremolo violin section articulations.Faced with the headache of keeping track of multiple playing styles across dozens of instruments, many composers opt to use a dedicated patch for each articulation. While that keeps things simple, it tends to generate a huge track count when applied to the entire orchestra, in a worst case leading to repetitive strain injury as you repeatedly scroll up and down the screen trying to locate those pesky pizzicato violas. An alternative, screen-real-estate-saving method is to use the custom keyswitching facilities supplied by some companies to create all-in-one keyswitch patches for your most commonly used articulations.

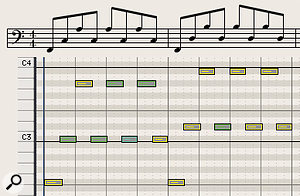

To arrange the five-way legato/sustain/spiccato/pizzicato/tremolo setup outlined above using VSL’s Vienna Instruments player, you’d drag and drop the respective patches one at a time onto a central ‘matrix’ grid, which can be stacked with as many as 144 patches (although that would be overdoing it). Once your five patches are loaded, click on the button to the right of the ‘X’ display, select Keyswitch, and the VI automatically creates a row of five adjacent keyswitches positioned outside (usually below) the playable range of the instrument and marked in blue on the GUI. The keyswitch pitches can be individually edited to taste; by pressing one of the five keyswitch notes, you can now switch articulations on the fly in real time (Diagram 1).

Diagram 2: A short musical passage featuring a different articulation in each bar.Using this setup, we can program passages with built-in articulation changes, as depicted in Diagram 2. (Note the ‘slur’ curved line over the first four notes, indicating that they should be played in a connected, legato style.) Diagram 3 shows the part and its keyswitches as displayed in Logic Pro’s Piano Roll Editor. You’ll notice that the legato notes in the first bar are deliberately overlapped: this is necessary to trigger the correct legato transition for each interval, but since legato patches are usually monophonic, the overlap won’t be audible.

Diagram 2: A short musical passage featuring a different articulation in each bar.Using this setup, we can program passages with built-in articulation changes, as depicted in Diagram 2. (Note the ‘slur’ curved line over the first four notes, indicating that they should be played in a connected, legato style.) Diagram 3 shows the part and its keyswitches as displayed in Logic Pro’s Piano Roll Editor. You’ll notice that the legato notes in the first bar are deliberately overlapped: this is necessary to trigger the correct legato transition for each interval, but since legato patches are usually monophonic, the overlap won’t be audible.

Diagram 3: The Piano Roll Editor display of the keyswitch sequence, showing the five keyswitches marked in red. In order to give your sample player a little time to process incoming MIDI data, it’s advisable to place keyswitches a few ticks or milliseconds in advance of the played notes.Libraries such as LA Scoring Strings and Cinematic Strings also offer fully customisable user keyswitches, while other collections provide preset keyswitch patches containing a well-chosen selection of related articulations. Most of these libraries allow you to move the keyswitches up and down in pitch, though they usually operate as a block and retain their adjacent semitone spacing. East West’s Hollywood Strings keyswitch positions can’t be edited, but by way of compensation, you can use the library’s ‘mod speed’ instruments to switch between different speeds of note attack, a useful programming aid.

Diagram 3: The Piano Roll Editor display of the keyswitch sequence, showing the five keyswitches marked in red. In order to give your sample player a little time to process incoming MIDI data, it’s advisable to place keyswitches a few ticks or milliseconds in advance of the played notes.Libraries such as LA Scoring Strings and Cinematic Strings also offer fully customisable user keyswitches, while other collections provide preset keyswitch patches containing a well-chosen selection of related articulations. Most of these libraries allow you to move the keyswitches up and down in pitch, though they usually operate as a block and retain their adjacent semitone spacing. East West’s Hollywood Strings keyswitch positions can’t be edited, but by way of compensation, you can use the library’s ‘mod speed’ instruments to switch between different speeds of note attack, a useful programming aid.

While generally seen as a helpful feature, keyswitching has some minor disadvantages: those who lack keyboard skills may find it confusing to have to play additional MIDI notes with the left hand to change articulations, while some composers complain that keyswitch notes mess up the look of their scores! Both problems have an easy solution: as mentioned last month, you can play a part first and add the keyswitches later, and composers can always make a ‘conductor’s score’ copy of a project with the keyswitch notes deleted. Alternatively, advanced users can use MIDI CC’s instead of keyswitches to select articulations, but that’s not something beginners need to worry about.

Diagram 4: A ‘mod speed’ patch from East West’s Hollywood Strings — the mod wheel can be used to switch between very short staccatissimo, short staccato, longer staccato and marcato deliveries, the speed of the note attack growing longer with each successive articulation.I have no fixed preference regarding keyswitches, and only use them when the musical situation demands it. That said, when programming solo instrument lead lines I find it absolutely essential to switch between different note lengths (sustain, portato, staccato and so on), as that greatly increases the realism and expressiveness of an exposed melody line. I’ll explain this in more detail in next month’s woodwinds article.

Diagram 4: A ‘mod speed’ patch from East West’s Hollywood Strings — the mod wheel can be used to switch between very short staccatissimo, short staccato, longer staccato and marcato deliveries, the speed of the note attack growing longer with each successive articulation.I have no fixed preference regarding keyswitches, and only use them when the musical situation demands it. That said, when programming solo instrument lead lines I find it absolutely essential to switch between different note lengths (sustain, portato, staccato and so on), as that greatly increases the realism and expressiveness of an exposed melody line. I’ll explain this in more detail in next month’s woodwinds article.

Trending Styles

Some thoughts on using the different string playing styles: as I frequently mention on these pages, the ‘true legato’ patches in today’s string sample collections are a superb aid to making melodies sound properly ‘joined-up’, so you’ll want to use that style for your important top lines. For less crucial inner parts, sustains are usually adequate; double basses rarely need the legato style, the exception being when they play an exposed or expressive passage.

The ‘spiccato’ articulation is now firmly established as the de rigueur string writing accessory for the fashionable composer about town. This short, zippy ‘action strings’ style is a great way of getting your music going, and can be heard in innumerable examples of TV, film and media music — apart from anything else, it’s great fun to play! The colourful ‘pizzicato’ plucked style also enjoyed a long run in media music circles, being dialled up at every opportunity in such masterpieces as Ugly Betty and Desperate Housewives to denote irony or comedy (often of the questionable variety). Nowadays pizzicato strings are used in TV productions as a ‘treading water’ device when the screen action is flagging, usually indicating a certain amount of desperation on the part of the director and composer. Still, if you can get those associations out of your head, it’s an enduringly lovely sonority, particularly when the samples are recorded in a concert hall acoustic.

Tremolo is the classic, traditional ‘Behind you!’ scary strings style. It sounds menacing when played by the low strings and tense when played by high violins, but it does have more subtle applications: you can, for example, layer it with sustains in quietly played chords, creating a magical shimmering effect. For delicate passages, it’s worth trying the lovely ‘sul tasto’ articulation, while muted ‘con sordino’ samples also bring out the strings’ soft and romantic side.

I’d be letting myself down if I didn’t mention the terrific ‘portamento’ Bollywood playing style, which features wonderful, lustily played pitch slides between notes. It’s still a relatively underused articulation, but I’m trying to rectify that by sneaking it into all my string arranging jobs! The ‘glissando’ style also employs uninhibited pitch-sliding, but it tends to be a slower, more exaggerated and comedic effect with Tom And Jerry-style cartoon music connotations.

Octave Doubling

I can remember as a young lad playing the piano and idly wondering why melody lines played in octaves seemed to acquire a sense of momentousness. Now I’ve learned a little about orchestral writing, the answer is obvious: composers frequently double their melodic themes in octaves, the classic example being second violins playing a tune in the middle register while the first violins double it an octave higher. Though I didn’t realise it at the time, my piano experiments were an unwitting evocation of that particular orchestral style.

A promising young student demonstrates the parts of the violin, but thankfully has not yet discovered the bow.When programming violins in octaves, it’s best to record the lower-register tune first. The temptation is then to copy the MIDI region onto another track and transpose it up an octave, but that tends to sound somewhat mechanical: it will sound a lot more convincing if you take the time to play in the high melody separately, as the ensuing (hopefully) minor discrepancies of timing between the upper and lower lines mirror the organic, non-identical performances of real musicians. (It will also sound more convincing than if you attempt to duplicate and then randomly ‘humanise’ the same part).

A promising young student demonstrates the parts of the violin, but thankfully has not yet discovered the bow.When programming violins in octaves, it’s best to record the lower-register tune first. The temptation is then to copy the MIDI region onto another track and transpose it up an octave, but that tends to sound somewhat mechanical: it will sound a lot more convincing if you take the time to play in the high melody separately, as the ensuing (hopefully) minor discrepancies of timing between the upper and lower lines mirror the organic, non-identical performances of real musicians. (It will also sound more convincing than if you attempt to duplicate and then randomly ‘humanise’ the same part).

Piano players instinctively double their left-hand bass parts in a lower octave, that being an effective way of adding power and size to a piano part. Classical composers do exactly the same thing with their low strings bass lines: the cellos play the upper part, while the basses double it an octave down. This is a tremendous, dramatic orchestral sonority which you’ll want to use in your string arrangements, and today’s sound companies know it: several contemporary sample libraries include cellos and basses recorded playing together in octaves, providing instant low-end power and size.

Though I usually dislike samples with built-in octaves, I have to say that these low-strings octave concoctions sound tremendous, and I’ve happily used them in my own work. I would, however, draw the line at using the same libraries’ octave violins patches for the reasons given above, though they might be useful if you want to quickly hear this classic orchestral effect in action.

Timing Tips

In Part 2 we looked at the ubiquitous ‘ostinato’ style (defined as a continually repeated musical phrase or rhythm) which many media composers use to inject movement into their scores. Such rhythmic figures need to feel good and impart rhythmic momentum. Here’s how to get started: when programming orchestral rhythm parts, you should always play to a click track, as a MIDI arrangement created with no relationship to tempo, bars and beats quickly becomes unmanageable in my experience. If you’re writing to picture, or orchestrating an existing recording which was played in free time, there are ways of generating a click based on a continually changing tempo in order to stay in time with the screen action or free-time recording. A Google search for ‘tempo mapping’ or ‘beat mapping’ will yield plenty of suggestions, but it’s fair to say that most explanations err on the side of geeky.

To sequence a simple strings rhythm part, select an incisive short-note style such as spiccato, set the click to a tempo you’re comfortable playing at (bearing in mind the speed can be changed later), and practise playing the first two or four bars. When you’ve mastered the part, record it into your DAW and play it back as a two or four-bar loop, leaving the click in the mix. Unless you have a metronomic sense of rhythm and have done such things a thousand times before, there are bound to be some small rhythmic irregularities — happily, these can easily be fixed by judicious use of quantising.

If your rhythm part consists of eight single notes per bar, feel free to slap on a hard eighth-note quantisation — this will place each MIDI note bang on the grid, providing a sound platform for all subsequent additions. If, however, your initial part features (for example) a repeated three-note chord, try a ‘soft quantise’ approach, using an eighth-note quantise setting of between 70 and 85 percent. This moves your played notes closer to the grid while maintaining the tiny timing differences between the chord’s individual notes, which sounds more relaxed and natural than a 100 percent ‘hard quantise’.

Another important factor to consider here is ‘sample timing slop’, as we call it in the trade. Orchestral samples almost always ‘speak’ late, because the producers (quite rightly) want to preserve the initial, faint stirrings of each sample’s note attack, thereby causing the main attack to occur a bit late. Sample slop is easily defeated: using a temporary 100 percent quantise setting on your part, play back your two or four-bar loop and listen to the relationship of the part with the click. The chances are it will sound at best lazy, at worst horribly late. To rectify this, highlight the MIDI region and adjust its ‘Delay’ setting to a negative number — say, minus 10 milliseconds. This has the effect of advancing the region’s MIDI playback timing, thus eradicating any inherent delay between it and the click.

Diagram 5: Use Logic Pro X’s Track inspector’s Delay setting to slide your MIDI parts into time with the click. Negative delay settings bring the notes forward in time, compensating for the built-in slow attacks one often experiences with sampled instruments.Diagram 5 shows the Delay setting in Logic Pro X’s Software Instrument Track inspector. It can be hard to judge when a part and click are bang in time: there’s absolutely no point fiddling around with tenths of a millisecond increments (not even Gavin Harrison can hear that tiny a delay), so I suggest trying applying 10, 20, 30 and 40 millisecond advances to your MIDI regions until the part sounds right. Sometimes the magic number is very high: expressive strings styles played with a slow attack often require a surprisingly large amount of timing advancement to sit right in a track. This approach preserves your original MIDI note positions as displayed in the Event List editor, so all you’re doing is applying a non-destructive global timing shift to the entire region. Note that different DAWs may use different terms here ‘delay’, ‘offset’ and so forth. If in doubt, consult your DAW’s manual.

Diagram 5: Use Logic Pro X’s Track inspector’s Delay setting to slide your MIDI parts into time with the click. Negative delay settings bring the notes forward in time, compensating for the built-in slow attacks one often experiences with sampled instruments.Diagram 5 shows the Delay setting in Logic Pro X’s Software Instrument Track inspector. It can be hard to judge when a part and click are bang in time: there’s absolutely no point fiddling around with tenths of a millisecond increments (not even Gavin Harrison can hear that tiny a delay), so I suggest trying applying 10, 20, 30 and 40 millisecond advances to your MIDI regions until the part sounds right. Sometimes the magic number is very high: expressive strings styles played with a slow attack often require a surprisingly large amount of timing advancement to sit right in a track. This approach preserves your original MIDI note positions as displayed in the Event List editor, so all you’re doing is applying a non-destructive global timing shift to the entire region. Note that different DAWs may use different terms here ‘delay’, ‘offset’ and so forth. If in doubt, consult your DAW’s manual.

Weaving Magic

Enough of such computer-centric technical stuff. Now seems like a good time to introduce an inspirational piece of music which brings together several of the string writing techniques mentioned above, and more besides. Titled The Race: Suite For Orchestra, it’s written by Mike Verta, a talented US composer with extensive experience of writing music to picture. Mike explains: “This piece began life as the score for an animated short (film) which was never completed. Since I’d already worked out the main themes and several plot moments, I decided to complete the work as a concert piece, while still retaining its original film-cue-like essence.”

Diagram 6: The opening two bars of The Race score extract played piano-style with block left-hand chords.The Race was recorded at L.A.’s Newman Scoring Stage at Fox Studios, with a full orchestra conducted by Neal Desby and engineered by Shawn Murphy. It’s fair to say the music comes from a classic tradition, drawing in part from the scores of great film composers such as John Williams (whose influence can be detected in this piece). This is not crash-bang-wallop, drum-heavy trailer / game music — it’s a properly through-composed, musically resourceful, well-orchestrated work which demonstrates the amazing versatility of the traditional symphony orchestra, and displays a big-screen mentality which wouldn’t sound out of place in a Harry Potter or Indiana Jones movie soundtrack.

Diagram 6: The opening two bars of The Race score extract played piano-style with block left-hand chords.The Race was recorded at L.A.’s Newman Scoring Stage at Fox Studios, with a full orchestra conducted by Neal Desby and engineered by Shawn Murphy. It’s fair to say the music comes from a classic tradition, drawing in part from the scores of great film composers such as John Williams (whose influence can be detected in this piece). This is not crash-bang-wallop, drum-heavy trailer / game music — it’s a properly through-composed, musically resourceful, well-orchestrated work which demonstrates the amazing versatility of the traditional symphony orchestra, and displays a big-screen mentality which wouldn’t sound out of place in a Harry Potter or Indiana Jones movie soundtrack.

Diagram 7: The static block chords are replaced by mobile eighth-note cello arpeggios which impart rhythmic momentum while defining the harmony — a classic orchestration device which would repay study by newbie composers!The extract I’ve selected features one of the piece’s two main melodic themes: played by strings around 35 seconds in, it’s a classic, uplifting heroic tune played over a very nice chord sequence. Diagram 6 (above) shows the opening melody as it might be played on piano, using block left-hand chords as accompaniment. However, in his desire to “dodge and weave and develop amidst an ever-present undercurrent of motion”, Mike avoided static block chords and instead wrote eighth-note arpeggios for the cellos (Diagram 7) and a simple repeated two-note pattern for the violas (Diagram 8).

Diagram 7: The static block chords are replaced by mobile eighth-note cello arpeggios which impart rhythmic momentum while defining the harmony — a classic orchestration device which would repay study by newbie composers!The extract I’ve selected features one of the piece’s two main melodic themes: played by strings around 35 seconds in, it’s a classic, uplifting heroic tune played over a very nice chord sequence. Diagram 6 (above) shows the opening melody as it might be played on piano, using block left-hand chords as accompaniment. However, in his desire to “dodge and weave and develop amidst an ever-present undercurrent of motion”, Mike avoided static block chords and instead wrote eighth-note arpeggios for the cellos (Diagram 7) and a simple repeated two-note pattern for the violas (Diagram 8).

This style of writing goes to the heart of traditional orchestral arrangement: unlike rock music, where the drums lay down a beat and other instruments play along, orchestral pulse is provided by the instruments themselves playing rhythmic parts, leaving the percussion free to add decorative and dramatic interjections.

Diagram 8: The violas play simple major-third figures over the cello arpeggios, the upward shift in the second bar shift marking the change from F major to G major.Diagram 9 is an eight-bar extract from ‘The Race’, played by violins (first and seconds combined in the top stave), violas, cellos and basses. (Apologies for not using the alto clef for the violas, but I need to keep this accessible.) Only the basses play long notes: the inner parts weave a mobile tapestry which imparts rhythmic momentum while defining the harmony of the chord changes, a technique which would-be orchestrators and composers would do well to study.

Diagram 8: The violas play simple major-third figures over the cello arpeggios, the upward shift in the second bar shift marking the change from F major to G major.Diagram 9 is an eight-bar extract from ‘The Race’, played by violins (first and seconds combined in the top stave), violas, cellos and basses. (Apologies for not using the alto clef for the violas, but I need to keep this accessible.) Only the basses play long notes: the inner parts weave a mobile tapestry which imparts rhythmic momentum while defining the harmony of the chord changes, a technique which would-be orchestrators and composers would do well to study.

Diagram 9: Extract from The Race, used by kind permission of its composer Mike Verta. Copyright 2011 Tudor-Ford Music, BMI.A video of The Race recording session can be seen at www.youtube.com/watch?v=xI1kdVtWKcU. The piece is also dissected at great length in Mike Verta’s ‘Putting It All Together’ online masterclass: www.mikeverta.com. Comments and discussion are welcome at Mike’s new composer’s forum: www.redbanned.com.

Diagram 9: Extract from The Race, used by kind permission of its composer Mike Verta. Copyright 2011 Tudor-Ford Music, BMI.A video of The Race recording session can be seen at www.youtube.com/watch?v=xI1kdVtWKcU. The piece is also dissected at great length in Mike Verta’s ‘Putting It All Together’ online masterclass: www.mikeverta.com. Comments and discussion are welcome at Mike’s new composer’s forum: www.redbanned.com.

Coda

I’ll leave you with a Mike Verta quotation, from an interview with Film Music magazine: “The intent is to have a convincing virtual orchestra and an emotional quality; that is the goal. But there are only so many hours in a day. If you want a truly convincing sound, you’re going to spend most of your hours on the performance of the samples, instead of on the music itself — the counterpoint, the orchestration, etc. So given that conflict I will always err on the side of the music — that’s where the emotional impact lies. A great piece of music can cure a lot of mediocre sample ills, but not vice versa.”

Wise words. In dealing with the challenges of working with samples, it’s important not to get bogged down in technical details. When you work on an arrangement for weeks, there comes a point when it’s hard to see the wood for the trees, and that’s the moment when you need to turn off your computer, step outside your music room, take a deep lungful of air and venture forth into the outside world. Believe it or not, there are people out there who will enjoy hearing your musical efforts, and while very few of them will be able to identify an over-loud note in the bassoon part, they’ll all respond favourably to the feel, energy and imagination of your music.

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 1 Getting Started

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 2 Basic String Writing

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 3 Essential String Playing Styles

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 4 Basic Woodwind Writing

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 5 Into The Woods

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 6 The Brass Family

String Playing Styles

Basic Styles

Legato: Fluid, ‘joined up’ melodic style (see also ‘Portamento’).

Sustain: Long note (played with or without vibrato).

Spiccato: Incisive staccato short-note style, effective at all dynamics.

Pizzicato: Plucked with the finger.

Tremolo: Fast alternating bowing on a single note — produces a shimmering, shuddering effect.

Staccato: Short note.

Staccatissimo: Very short note.

Marcato: Heavily accented, forceful.

Trill: Rapid alternation between two notes with the left hand under a single bow movement.

Extended Techniques

Portamento: A variant of the legato style featuring Bollywood-style pitch slides between notes.

Espressivo: Played with strong (‘molto’) vibrato, used for romantic, dramatic and expressive passages.

Sforzato: Played with a sudden, strong, forceful attack.

Sforzatissimo: Extreme version of above.

Flautando: Light, fast bowing over the fingerboard — produces a soft, breathy flute-like sound.

Sul tasto: Soft, warm delicate tone played over the fingerboard (similar to flautando).

Con sordino: Muted — a softer tone produced by attaching a small rubber mute to the bridge.

Sul ponticello: Thin, edgy sound produced by playing very close to the bridge.

Col legno: Struck with the back of the bow, producing a light percussive attack.

Bartók pizzicato: The string is pulled up then released to snap against the fingerboard, creating a highly percussive twangy effect.

Harmonics: High-pitched ethereal notes created by lightly touching a point on the bowed string.

Glissando: Smooth pitch slide between notes.

Grace note: Very short, ornamental note (or group of notes) played immediately before a main note.

Octave runs: Performed scale run played over a single octave or multiple octaves.

Played Dynamics

Crescendo: Rising in volume.

Diminuendo: Decreasing in volume.

Fortepiano: A note which starts out loud, then dwindles in volume.

Pfp: A quiet note which grows in volume to a loud dynamic, then subsides.

Other styles which crop up in sample libraries include portato (medium-length, melodic ‘carrying’ notes), détaché (separated, alternating up and down bowstrokes for rhythmic passages), martelé (literally ‘hammered’ — not in the alcoholic sense, but meaning a hard, abrupt bow attack) and ‘ricochet’ (aka jeté), a wild, leaping, bouncing bowing style used to produce a series of rapid notes.

You’ll also encounter performances such as double and triple note attacks, various types of fast note repetitions and ‘measured tremolo’ (a version of the above-mentioned tremolo style played in tempo as fast 150-200 bpm 16th notes). Though sometimes a little tricky to synchronise, such performances can add instant excitement and drive to an arrangement.

You can hear most of these playing styles in action at www.vsl.co.at/en/Instrumentology/Strings.

Solo Strings Libraries

These contemporary sample libraries feature exclusively solo instruments; string section libraries (some of which include solo instruments) are listed in the previous article of this series. The libraries are listed by manufacturer, then by library name, then instrument(s), abbreviated as follows:

Vn: First violin

Vn2: Second violin

Va: Viola

Ce: Cello

Db: Double bass

The figures in square brackets [n] indicate the number of microphone positions excluding any mixes, while the GB number shows the total size of the library (including all volumes) in Gigabytes once installed on your hard drive. So, for example, the first entry for VSL Solo Strings I & II includes first violin, viola, cello and double bass, captured using one mic position, and it occupies 86.6GB on your drive.

Vienna Symphonic Library www.vsl.co.at

- Solo Strings I & II Vn, Va, Ce, Db [1] 86.6GB

EastWest / Quantum Leap www.soundsonline.com

- Hollywood Solo Violin Vn [5] 39GB

- Hollywood Solo Cello Ce [5] 40.7GB

Spitfire Audio www.spitfireaudio.com

- Sacconi Strings — Quartet Vn, Vn2, Va, Ce [6] 70.7GB

- Solo Strings Vn, Va, Ce [3] 6.2GB

- Artisan Violin Vn [6] 7.8GB

- Artisan Cello Ce [6] 7.6GB

Orchestral Tools www.orchestraltools.com

- Berlin Strings First Chairs Vn, Vn2, Va, Ce [2] 33.2GB

- Nocturne Violin Vn [2] 4.7GB

- Nocturne Cello Ce [2] 2.7GB

Cinesamples www.cinesamples.com

- CineStrings Solo Vn, Vn2, Va, Ce, Db [3] 50GB

Kirk Hunter www.kirkhunterstudios.com

- Spotlight Solo Strings Vn, Va, Ce, Db [1] 5GB

- (Vn, Va and Ce have four variants, Db has 2)

Strezov Sampling www.strezov-sampling.com

- Macabre Solo Strings Vn, Va, Ce [2] 4.5GB

Embertone www.embertone.com

- Friedlander Violin Vn [1] 3.5GB

- Fischer Viola Va [1] 4.3GB

- Blakus Cello Ce [1] 3GB

- Leonid Bass Db [1] 4.2GB

Chris Hein www.chrishein.net

- Solo Violin Vn, Vn2 [1] 4GB

- Solo Viola Va [1] 4GB

- Solo Cello Ce [1] 4GB

- Solo Contrabass Db [1] 4GB

- (Ce has two variants)

Samplemodeling www.samplemodeling.com

- The Violin Vn [1] unpublished

- The Viola Va [1] unpublished

- The Cello Ce [1] unpublished

Virharmonic www.virharmonic.com

- Bohemian Violin Vn [1] 4.6GB

- Bohemian Cello Ce [1] 5.3GB

Harmonic Subtones www.bestservice.de/en/emotional_cello.html

- Emotional Cello Ce [2] unpublished

Recommended Listening

Though Hollywood-style ‘epic’ brass sample libraries enjoyed a brief period of dominance a few years back, a subsequent wave of high-end strings collections signalled a renewed commitment to high-quality strings products. Here are some demos which show the scope of the modern sampled string orchestra, listed in company-name alphabetical order. (Note that some demos feature a full orchestra.)

8Dio https://8dio.com/instrument/bundle-9-all-adagio-strings

- The Iron Mask Opening (Antongiulio Frulio)

Audiobro http://audiobro.com/demos/music

- Xolotl (Ian Livingstone)

EastWest www.soundsonline.com/hollywood-strings (under audio demos)

- Hollywood Spiccati (Antongiulio Frulio)

Orchestral Tools www.orchestraltools.com/libraries/berlin_strings.php

- Sky Passage (Blakus)

Spitfire Audio www.spitfireaudio.com/shop/a-z/spitfire-symphonic-strings

- The Captain Evades Capture (Rohan Stevenson)

Vienna Symphonic Library www.vsl.co.at/en/Music/MusicPlaylists

- Adagio for Strings (Samuel Barber, programming by Michael Hula)

I also enjoyed these solo strings product demos:

Orchestral Tools www.youtube.com/watch?v=G1UKlk-fOHc

- Nocturne Violin screencast (Hendrik Schwarzer)

Spitfire Audio www.spitfireaudio.com/shop/instruments/strings/sacconi-strings-quartet

- The Luthier (Quartet) (Andy Blaney)

Vienna Symphonic Library www.vsl.co.at/en/Music/MusicPlaylists

- String quartet op. 59/3 — Finale (Beethoven, prog. by Jay Bacal)