Kesha Lee at LA’s Conway Studios.

Kesha Lee at LA’s Conway Studios.

Not only is Atlanta’s rap scene producing stars like Lil Uzi Vert, but it’s also providing opportunities for a new wave of engineering talent.

This is the 132nd article in Sound On Sound’s Inside Track series, and it’s a sad reflection of the state of the music business that only three female engineers have featured in the first 131. What’s more, persuading the fourth to take her turn in the spotlight proved surprisingly difficult. Kesha Lee explains that she is uneasy about doing an interview because she’s only been doing this job for four years, and that “as an engineer coming up in Atlanta, the setup or process is a lot less involved gear- and session-wise than it may be in other places”.

Lil Uzi Vert.Photo: Spike JordanIn that time, however, Lee has worked with the likes of God 1st †, Gucci Mane, Travis Scott, Playboi Carti, Future, Pharrell Williams, TI, Jeremih, Young Thug, Migos and Chance The Rapper — and now has a US number one album, courtesy of Luv Is Rage 2, the debut album by Atlanta rapper Lil Uzi Vert. It took a bit of persuading to make clear that having engineering and mixing credits on a chart-topping album make Lee a perfectly valid interview candidate! Eventually a Skype conversation ensued, in which Lee shared her story and that of the making of Luv Is Rage 2.

Lil Uzi Vert.Photo: Spike JordanIn that time, however, Lee has worked with the likes of God 1st †, Gucci Mane, Travis Scott, Playboi Carti, Future, Pharrell Williams, TI, Jeremih, Young Thug, Migos and Chance The Rapper — and now has a US number one album, courtesy of Luv Is Rage 2, the debut album by Atlanta rapper Lil Uzi Vert. It took a bit of persuading to make clear that having engineering and mixing credits on a chart-topping album make Lee a perfectly valid interview candidate! Eventually a Skype conversation ensued, in which Lee shared her story and that of the making of Luv Is Rage 2.

Second Chances

Born 28 years ago in Alabama, Kesha Lee’s first musical exploits involved played violin at middle school, and later playing the clarinet. Her father was into music, and encouraged her to play the piano, and to get to grips with the modern world of DAWs, even going as far as to buy her a laptop with Pro Tools. However, they both found it rather hard to make sense of Pro Tools. Other DAWs were tried, but Lee drifted into non-music jobs, like working in restaurants.

“I really wanted to work in music,” Lee recalls, “but did not know where or how. I was friends on Facebook with someone who was a radio personality at the local radio station, 98.7 Kiss FM in Birmingham, Alabama, so I asked whether they were hiring. This led to me doing an internship and later being offered a job for one day a week. I ended up cutting in commercials using Adobe software. People’s voices were sped up for the commercials, and then pitched down again, so I learned about that. I realised that I didn’t really want to continue with broadcasting, because I was in a room by myself all the time, and I looked into audio engineering. Around that time my mother bought a Mac for my brother, and I started playing around with GarageBand on that, and it was much more simple and straightforward to use than the programs my Dad and I had been working with.

“What attracted me to engineering was to be able to add all these effects to audio. I did not know that you could do that, but GarageBand really got me into that. So I started looking around for a school, and ended up doing an 11-month audio engineering course at the Atlanta Institute of Music. In my last quarter there I began sitting in on Gucci Mane’s sessions with his engineer Sean Paine, at Patchwerk Recording Studios, and also on Future recording sessions with Seth Firkins. I wasn’t really an engineer yet, but Seth invited me to sit in and taught me a lot of stuff. Once I graduated he figured that I should, instead of sitting in, be working, but I’d still regularly go round and he’d allow me to practice on his setup and ask questions about things I didn’t understand.”

Social Scene

After graduating from the Atlanta Institute of Music in September 2012, Lee continued to benefit from the fact that the Atlanta scene is exceptionally vibrant, with new rappers regularly breaking through nationally and internationally. At the same time, the scene is also small enough for everyone to know everyone, and hanging out on each other’s sessions is the norm. In fact, Atlanta recording sessions are social gatherings, worlds away from the hushed and almost sacred ‘don’t disturb’ atmosphere that has often been the norm in recording studios. This even leads to the ironic situation of Lee regularly having to don headphones while recording a rapper who is in the booth, because the guests in the control room are making too much noise!

“Yes, everything in the studios in Atlanta is really chilled and vibey. There never really is a problem with artists and producers popping in on each other’s sessions and stuff like that. The rappers and producers are for the most part very open-minded, and don’t have a problem bouncing ideas off each other. They also like to work very fast and as an engineer in Atlanta you have to keep up with them. You can’t be too concerned and technical about signal chains and sound customisation. You may want to switch the microphone for another rapper, or try a different vocal chain, but they don’t care about that, they just want to get their ideas down. And yes, if there are a bunch of people in the room, and they’re watching a game and don’t want to turn it down, and I really need to hear what the rapper is doing, I will put on my Sennheiser HD280 headphones.

“I haven’t actually encountered any problems working as a woman in the studio, because I’m at the desk, focused on a screen, and everybody is behind me. People don’t really talk to me when I am working. There have been two or three instances when people were offended to find a girl engineer, and assumed that I didn’t know what I am doing — but they came round. I have the hardest time with people who know how to use Pro Tools, because instead of telling me what they want, they tell me how to do it, which takes me out of my workflow. There are three ways to do everything in Pro Tools. I know many hotkeys and am really fast with them. So it is: ‘Just tell me what your end goal is!’”

On The Road

The social and interactive nature of the Atlanta rapping scene helped Lee to quickly gather a very impressive list of credits after graduating, as mentioned above, which also includes being a recording engineer for well-known Atlanta beatmakers like Metro Boomin and Zaytoven. A meeting with Atlanta beatmaker and producer Don Cannon, who is close to Symere Woods, aka Lil Uzi Vert, resulted in Lee working regularly with the rapper. Since 2015, Lee has engineered all three EPs and four mixtapes Uzi Vert has released to date, as well Luv Is Rage 2. She also mixed four songs on the rapper’s debut album; the others were mixed by well-known mixers Jaycen Joshua and Leslie Brathwaite. However, as we shall see, and as Lee herself already hinted at, being an engineer and mixer in the Atlanta rap world is a rather different proposition from most other places.

Preliminary work for the album took place in December 2016, with the core team of Uzi Vert, Don Cannon and Lee. Next up was a trip to Hawaii at the beginning of 2017, suggested by the label, Atlantic. “The first days after we arrived we were jetlagged, and the studio where we were booked to work, Island Sound, was rather far from the house where we were. So we ended up just setting up a work station in the house. The audio wasn’t the best, but the vibe was great.

Preliminary work for the album took place in December 2016, with the core team of Uzi Vert, Don Cannon and Lee. Next up was a trip to Hawaii at the beginning of 2017, suggested by the label, Atlantic. “The first days after we arrived we were jetlagged, and the studio where we were booked to work, Island Sound, was rather far from the house where we were. So we ended up just setting up a work station in the house. The audio wasn’t the best, but the vibe was great.

“We were supposed to be in Hawaii for a month, but only stayed for two and a half weeks. After that we spent a couple of weeks in LA, and then we came back to Atlanta, where we worked on the album until August, at Means Street Studios. It was full-time. My schedule was insane. The last two months I had two days off each month, and one of the days was because I was moving into my apartment, and the other day I still had to work. There were times when I didn’t sleep for days! Throughout, the only times we weren’t working was when Uzi would do a show. Those times gave me a chance to try out some ideas I had for the songs, editing certain sections and mixing, but after a while I stopped, because I wasn’t sure what songs he was going to pick.

“The reason the recordings took so long was because it was Uzi’s first album, and he wanted to top his last body of work. He knows what he wants with regards to the beats he raps over, but we often can’t figure out what sound he is going for. So there was a lot of recording, and at some stage the songs he’d recorded a while back were old to him, and he wanted to record new stuff. Sometimes he uses a beat as it is, sometimes he’ll like a certain part of the beat and he will ask for it to be looped, so there was a lot of arranging the tracks how he wanted them. Or I’d do an effect that he would like, and he would want that for the song. Or we would have a producer come in and make a beat on the spot. There were a couple of occasions where a producer would come in and Uzi would help them make a beat, or he’d do the drums. I think he did the drums on ‘Two®’, the album’s opening track.”

Starting With The Beat

Rewinding a little, Lee elaborates on the process by which Uzi Vert, Cannon and she created the album. “People either email Uzi beats, and he forwards them to me, or I will reach out and say ‘Hey, we are in the studio, can you send some beats?’ I will pull up these beats, and often he wants to hear everything before he picks something. He doesn’t really like listening to each beat in too much detail before he goes into the booth, he just goes in and records. He doesn’t do like a whole verse, instead he’ll do things line by line, and I’ll be punching in. The producers send two-track MP3s, and depending on who the producer is, and if Uzi really likes the song, I will get the track-out. But I don’t want to get too far into editing a two-track if I later have to replicate those edits on a track-out.

“Uzi will have all his friends in the studio, but just the three of us work on the music. Cannon makes beats or he will play more of an executive producer role, where he gets beats from other people. Uzi does his own thing. I will even let him do his own drops, where you only hear him and there’s no music playing. I will put the track on latch automation, and I will let him press the mute button so he can do his drops when he wants them, and then when he clicks mute again, the track will come back in. He will do this totally intuitively. Many of the drops will come in on the one, but if the latch automation didn’t catch that on the one, I will go back in later and I will move everything to where it is supposed to be, so the drop is clean.”

Obviously, ‘track-out’ is the Atlantan studio word for exporting all the individual tracks or stems from a DAW recording session. Working with just the two-track MP3 instead greatly simplifies Lee’s job.

It turns out that the Atlantan approach to recording is unusually straightforward in other respects as well, at least in a rap environment. “The standard for Atlanta seems to be to use Yamaha NS10s or Augspurger monitors,” Lee explains, “and the recording signal chain consists of an Avalon VT-737sp mic pre and a Tube-Tech CL 1B compressor. The microphone is normally a Neumann U87 and the headphones are Sennheiser HD280s. We briefly used the U87 when we got back from LA, because that’s what’s in Means Street Studio A, but Uzi likes the Neumann TLM103, which is in Studio B, and which we use most of the time.”

Lee did not record any musical instruments on the album, apart from an electric guitar overdub to one song called ‘The Way Life Goes’, during a session at Germano studios in New York. An almost obligatory addition to any rap album these days appears to be the involvement of a few celebrity singers, with Pharrell Williams and the Weeknd particularly popular. Both feature on Luv Is Rage 2; the Weeknd sent in his vocal contribution, while Williams’ vocals were recorded during the lay-over in LA. Lee had expected to just be watching Williams’ regular engineer record him, but instead she ended up behind the controls at Conway. “I imported my template for the song ‘Neon Gets’ into his track-out session, and Pharrell was down to use whatever Uzi was comfortable with, so as I mentioned, we used the [Neumann] TLM 170, and the Avalon. So that was very easy.”

Lee’s mixes for Luv Is Rage 2 were done entirely on her laptop, often with just the built-in audio I/O and a pair of Sennheiser headphones. This photo was taken at Means Street Studios in Atlanta.

Lee’s mixes for Luv Is Rage 2 were done entirely on her laptop, often with just the built-in audio I/O and a pair of Sennheiser headphones. This photo was taken at Means Street Studios in Atlanta.

Keeping It Simple

Apparently, the intention was for Lee and Don Cannon to do all the final mixes, but time pressure meant that many of the album songs were given to Joshua and Brathwaite to mix. However, since Lee’s mixes were very largely based on the two-track file of the original beat, her mix work involved essentially doing a vocal mix and balancing that the beat. Lee in fact conducted many of her mixes at home, using just the basic Mac soundcard and her $99 Sennheiser headphones.

“I use a three-year old MacBook Pro, and Cannon recently bought me the [UA] Apollo Twin, so I want to get into using that. In general, I want to be able to be completely work on my laptop wherever we go, because even the Pro Tools systems in the bigger studios don’t have certain plug-ins. I also don’t use the desk for anything more than the volume button for the monitors and the switch for speakers. I’ve tried mixing during the sessions, but there’s so much going on that it’s hard to concentrate and really listen to things. So I prefer to mix in my own space, away from people. And I figured, most people listen to music on their laptops or phones using earbuds, so why not mix how they are going to hear it? I will check my mixes on the speakers in the studio, but I am really comfortable with my Sennheiser HD280s.”

Talking Mixing

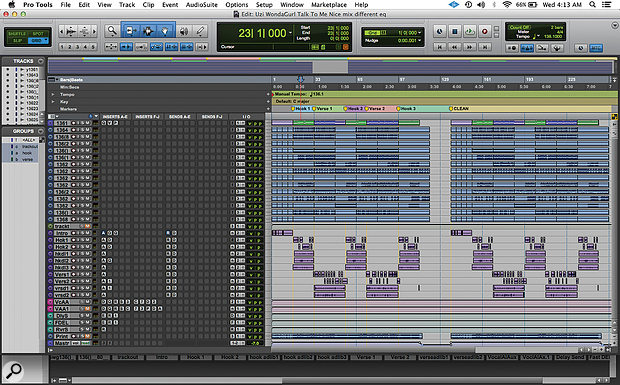

The mix session for ‘How To Talk’ is modest by modern standards, containing only 33 tracks — of which almost half were not used. These break down in the stereo mix of the beats at the top, 14 beat audio tracks, one beat aux, 10 audio vocal tracks, two vocal aux tracks, three effect aux tracks for the vocals (delay, fast delay, reverb), a mix print track and a master track.

Lee: “The two-track at the top is colour-coded purple and green, for organisational purposes, so it’s really easy to spot where the hook is. The hook is always green. This also helps Uzi, so he knows where the hook ends and where the verse comes in. The two-track has three plug-ins. The ‘Q’ is the Avid EQ3 seven-band, which I used to turn down the volume of the track. The ‘V’ is the Waves Vitamin Sonic Enhancer, and the ‘P’ is the UAD Precision EQ, which was added by Cannon. There is not much I can do to the two-track, but I added the Vitamin to play with some of the frequencies and bring out the highs a little bit. Below the two-track are the track-out tracks, all in blue. We did not go with that track-out, so I muted the aux for it.”

The full mix session for ‘How To Talk’ contains the ‘track-out’ or stems for the beat, but these were muted in Kesha Lee’s actual mix.

The full mix session for ‘How To Talk’ contains the ‘track-out’ or stems for the beat, but these were muted in Kesha Lee’s actual mix.

Vocals

The essential effect for today’s rapper: Antares Auto-Tune is, says Kesha Lee, invariably the first plug-in on every vocal track with Lil Uzi Vert.“The intro track was a voice note Uzi had recorded on his phone, and he played it in the booth on his phone, and we recorded it through the mic like that. It sounded really telephone-y, which we wanted, but I tried to take out some of the highs with the Waves OneKnob. All audio vocal tracks apart from the intro have Antares Auto-Tune as the first plug-in. Uzi hears his Auto-Tuned vocals in his headphones while singing. We used to just have it on default, with a Retune speed of 20, but lately he has been like: ‘Give me more Auto-Tune!’ so now we have the Retune Speed set to anywhere from 12 to 5. The ‘D’ after Auto-Tune is the Waves De-Esser, the ‘Q’ the Avid EQ3 seven-band, and the ‘1’ is the Waves C1 gate. All vocal audio tracks also have sends to the delay and the reverb aux tracks. The delay aux track has the Avid Mod Delay II set to half notes, with feedback at 43 percent, the Waves Renaissance Reverberator, set to ‘Hall 1’ reverb, with the highs cut on the reverb EQ, and the Waves S1 stereo imager. The reverb aux has the Renaissance Reverberator.

The essential effect for today’s rapper: Antares Auto-Tune is, says Kesha Lee, invariably the first plug-in on every vocal track with Lil Uzi Vert.“The intro track was a voice note Uzi had recorded on his phone, and he played it in the booth on his phone, and we recorded it through the mic like that. It sounded really telephone-y, which we wanted, but I tried to take out some of the highs with the Waves OneKnob. All audio vocal tracks apart from the intro have Antares Auto-Tune as the first plug-in. Uzi hears his Auto-Tuned vocals in his headphones while singing. We used to just have it on default, with a Retune speed of 20, but lately he has been like: ‘Give me more Auto-Tune!’ so now we have the Retune Speed set to anywhere from 12 to 5. The ‘D’ after Auto-Tune is the Waves De-Esser, the ‘Q’ the Avid EQ3 seven-band, and the ‘1’ is the Waves C1 gate. All vocal audio tracks also have sends to the delay and the reverb aux tracks. The delay aux track has the Avid Mod Delay II set to half notes, with feedback at 43 percent, the Waves Renaissance Reverberator, set to ‘Hall 1’ reverb, with the highs cut on the reverb EQ, and the Waves S1 stereo imager. The reverb aux has the Renaissance Reverberator.

The RN Digital Detailer made Uzi’s vocals sound fuller and wider.“All audio vocal tracks go to the vocal aux track. I had two vocal aux tracks in this session, because I wanted to try something different, using plug-ins I don’t normally use. That’s why one of the aux tracks is muted. The vocal aux track that I did use has the Waves De-Esser acting around 4230Hz, then the EQ3 seven-band which has a high-pass at 96.4Hz, and I’m dipping out muddiness at 200 and 500 Hz. I’m also adding some high end at 6.52kHz. I don’t normally add EQ with the seven-band, but Seth would add some high end on Future’s voice and that worked well, so I tried it here. Next is the Waves Renaissance Compressor, to keep the dynamics in check, and then the Waves SSL E-channel, on which I am again dipping out various frequencies. The latter plug-in is more for colour and character. The Waves CLA-3A is more for the sound, and the RN Digital Detailer made Uzi’s vocals sound fuller and wider.

The RN Digital Detailer made Uzi’s vocals sound fuller and wider.“All audio vocal tracks go to the vocal aux track. I had two vocal aux tracks in this session, because I wanted to try something different, using plug-ins I don’t normally use. That’s why one of the aux tracks is muted. The vocal aux track that I did use has the Waves De-Esser acting around 4230Hz, then the EQ3 seven-band which has a high-pass at 96.4Hz, and I’m dipping out muddiness at 200 and 500 Hz. I’m also adding some high end at 6.52kHz. I don’t normally add EQ with the seven-band, but Seth would add some high end on Future’s voice and that worked well, so I tried it here. Next is the Waves Renaissance Compressor, to keep the dynamics in check, and then the Waves SSL E-channel, on which I am again dipping out various frequencies. The latter plug-in is more for colour and character. The Waves CLA-3A is more for the sound, and the RN Digital Detailer made Uzi’s vocals sound fuller and wider.

Nomad Factory’s MCL-2269 Limiter & Compressor was used to warm up the beat, along with RN Digital’s unusual Detailer plug-in."The final plug-in in the chain is the Nomad Factory MCL-2269 limiter and compressor, again for the sound and for more volume. We always go for a warm, full, loud, in-your-face vocal sound, also because we like the vocals to be louder than the beat. I always turn the beat down 1-2 dB. There are no plug-ins on the master track, because I used to work for a producer who didn’t want that, as the mix would go to the mastering engineer. So I’m still used to doing it like that. I turn the master volume down anywhere between -7 to -9 dB before it goes to mastering, so they have room to work with.”

Nomad Factory’s MCL-2269 Limiter & Compressor was used to warm up the beat, along with RN Digital’s unusual Detailer plug-in."The final plug-in in the chain is the Nomad Factory MCL-2269 limiter and compressor, again for the sound and for more volume. We always go for a warm, full, loud, in-your-face vocal sound, also because we like the vocals to be louder than the beat. I always turn the beat down 1-2 dB. There are no plug-ins on the master track, because I used to work for a producer who didn’t want that, as the mix would go to the mastering engineer. So I’m still used to doing it like that. I turn the master volume down anywhere between -7 to -9 dB before it goes to mastering, so they have room to work with.”

Not A Bad Start

Luv Is Rage 2 was released on August 25th, and debuted at the top of the Billboard 200 chart. Despite the fact that this surely is a life-changing event for a young engineer and mixer only four years into her career, Lee appears remarkably modest about her achievement, preferring to focus on the fact that she still has a lot to learn. “Of course I think it’s cool, and it’s exciting to have worked on something that many other people like. But it’s mostly others who get excited about it. They make you realise that having a number one is a big deal.

“I freelance, so when Uzi goes out promoting the album I continue working, but I also am taking care of stuff I’ve neglected while I was working on his album. It would be easy to just continue working as I have been here in Atlanta, but actually, I still have a lot of growing to do. Mixing kind of fell into my lap, and because of what happened I want to learn more about it and get better, but I actually love recording, and also want to get more into editing. I’m also really excited to go to the AES in New York this Fall, and I want to find new gear and try out more microphones and different preamps. So mostly I’m getting my life organised and getting ready for all these upcoming trips. And when Uzi gets back, I’ll be working with him again. He spoke of a few projects he wants to do.”

Project Management

One of the biggest challenges that faced Kesha Lee during the eight-month production process for Luv Is Rage 2 was organising, saving and archiving everything. “This was my first album project from beginning to end, on which I was both a recording and a mixing engineer, so I had not handled a project of this size before. Each day I created a folder with the date and the time, and inside each folder we would have the name for each song, the name of the producer, and Uzi’s name. If the song wasn’t finished, I would mark what he had done, and I soon also put the tempo and the key in the file name, because they often ask me for that, and I did not want to have to open the session just to get that information. At the end of the month I would have organised the sessions into finished, unfinished and collaborations. Because often Uzi would say something like, ‘Can you put up that song that I did not finish with Metro?’ It was just easier to find stuff that way.

“I would do the best rough mix that I could do while recording, because I knew that we would be moving onto another song, so I tried to do as much as I could during the sessions. If I went back to a song it was because I had an idea for something I could fix or improve, but not only would I never be sure whether a song would be used or not, Uzi would also listen to the songs a lot, and he’d get used to hearing it a certain way, so I had to be very careful about changing things. Plus he did go in again to change certain songs, because he had new lyrics or wanted to add stuff.

“If I had the track-out, I might mute a certain instrument, or I’d chop the beat up. I like doing snare hits or duplicating the kick or 808 in certain spots, or use SoundToys to change the sound. I’d always make notes of what I did, so I could replicate it, if required. We did get the track-out for all the songs, but in some cases the track-out was not the same as the two-track, and because Uzi gets so attached to the version of the song he’s worked with, we then simply mixed using the two-track. Also, even if I did mix with the track-out, I’d try to match that to the two-track.”