Kevin Kadish at The Carriage House.

Kevin Kadish at The Carriage House.

Channelling their shared love of ’50s kitsch, Kevin Kadish and Meghan Trainor created 2014’s most talked-about hit single — and turned Trainor into a superstar overnight.

Meghan Trainor’s ‘All About That Bass’ has topped hit parades in two dozen countries, including the US — where it went four times platinum, with well over four million sales, and was recently nominated for two Grammy Awards — and the UK, where it went ‘only’ platinum with more than half a million sales. During its extended reign at the top, ‘All About That Bass’ also was the world’s most discussed song, its celebration of big bass, aka big booty, aka big bum, proving the source of endless controversy.

The song’s staggering success has catapulted the two protagonists behind it from relative obscurity into the limelight. Singer Meghan Trainor was only 20 when it was released, and had until then not really aimed at being an artist. Originally from Massachusetts, her ambition was to be a songwriter, and she was signed to Big Yellow Dog Music, a Nashville publisher, after winning the 2011 Sonicbids Tennessee song contest at the age of 17. In the Spring of 2013 her publisher Carla Wallace had the bright idea of introducing Trainor to musician, writer, engineer, mixer and producer Kevin Kadish. Wallace must still be feeling pretty pleased with herself, for a couple of hours into their first writing session together, Trainor and Kadish had co-written and recorded most of ‘All About That Bass’.

Kevin Kadish’s rise to the top has also been the subject of a sizeable number of articles, with the press sometimes presenting his as a rags-to-riches tale. On the phone from his Nashville studio, Kadish admits that the success of ‘AATB’ has turned his life upside-down, but stories of a dramatic transition from zero to hero have been greatly exaggerated. “This is my first global number one, so yes, it is a life-changer! And yes, I may have slept on friends’ couches and been totally broke at one point, but that was a long time ago. The success of ‘All About That Bass’ did not come out of the blue. I’ve been making a living for 15 years as a songwriter and a producer and even before the release of ‘All About That Bass’ I had sold around 15 million records and had enjoyed several hit singles, including top five and top 10 songs.”

Don’t Worry About The Radio

Kadish’s studio, called The Carriage House, is a state-of-the-art facility located in his property near Nashville. It’s professionally designed by Ross Alexander and fitted with exquisite kit, such as an 8:2 tube Dymaxion sidecar desk made by Ian Gardiner of Boutique Audio & Design and Steve Firlotte of Inward Connections, as well as mic pres and compressors by Chandler (LTD1), Daking (52270), Burl (B1D), Classic API (VP28), Tube-Tech (CL1B), and outboard by Retro Instruments (Sta Level), Empirical Labs (Distressors), Helios (F760), Chandler (TG1) and more, plus Adam S3A and Yamaha NS10 monitors.

Born and raised in Baltimore, Maryland, Kadish studied at the Berklee College of Music in Boston and the University of Maryland, graduating in 1993 in Music Management. As an artist in his own right, he toured in support of some pretty big names in the ’90s, and he got his first big break when meeting producer Matt Serletic (Cher, Stacie Orrico) in 2000. He worked with Serletic for 10 years, acting as the producer’s staff writer and co-writing songs for the likes of Willie Nelson and Stacie Orrico (including her worldwide hits ‘(There’s Gotta Be) More To Life’ and ‘Stuck’. Kadish also collaborated with Jason Mraz on the latter’s Mr A-Z album in 2005, which earned him his first Grammy Award nomination, for Best Engineered Album. In addition, Kadish has co-written songs for and with a wide range of artists from Miley Cyrus to Meat Loaf, and Joe Jonas to Skillet.

Kadish moved to Nashville in 2006, and it was here that the magic that resulted in ‘All About That Bass’ took place. “The thing with Meghan happened completely out of the blue,” recalls Kadish, “and the songs also came out of the blue. She did not have a record deal, we just wrote songs that we liked, and didn’t worry about the radio. I love 1950s and early 1960s music, and had wanted to make an EP of music inspired by that era for a long time. Meghan and I bonded over our mutual love of the Jimmy Soul song ‘If You Want To Be Happy’, and we decided to do an EP inspired by the 1950s and then find out whether anyone would like it.”

The Reluctant Engineer

“I am primarily a guitar player and singer,” elaborates Kadish. “And I can program drums and keys. I learned engineering out of necessity. I got my first Pro Tools rig when working with Matt Serletic, a Digi 001. I had never used Pro Tools, or really engineered, before that. I had owned some ADATs and four-track cassette recorders when I was at high school, but never considered myself an engineer. But since that first Pro Tools system I have definitely learned a lot about engineering, and what I like and don’t like.

“As a result I now have a setup that could be considered old-school in that it’s not a laptop studio but actually a proper recording studio, with a full tracking setup, including a drum room, a vocal booth, an amp booth and so on. I love my analogue gear and my Dymaxion desk, which has eight 610 preamps that sound incredible and Abbey Road Studio airplane-style faders. I use it purely for tracking. I also am a fan of the Classic API stuff, which comes as a kit and you then have a tech build it for you. These Classic API kits sound incredible. But do I need all this gear to make records? No. I personally just like having the options of the preamps and compressors and mics. I tend to track pretty clean. I like to get good sounds at source and if I want it distorted or otherwise processed, I can do this after the fact. Also, not everything I do is retro. I can do retro, or non-retro, in my studio, as I prefer.

“More often than not people come to my studio to work with me, but it is not a requirement. For me writing here is easy, of course, because I have all my favourite gear. I often start with programming a beat so I know what the groove is going to be and it helps to keep the melodies consistent phrasing-wise. You want to make sure that things are not dragging. These days I program drums in Native Instrument’s Maschine. I make my own kits, using my own samples, and I love it. It has taken my drum programming to a whole other place. I work with both the software and the controller, and I exclusively work in Pro Tools. Also, I don’t have an assistant. I do everything by myself here, writing, recording, editing, and mixing.”

A Chorus Of Choruses

Because Kadish and Trainor were under no pressure whatsoever, they felt free to experiment, leading ‘AATB’ to be, in Kadish’s words, “sort of an anti-chorus song. There’s no clear structure to the song. The first verse is nothing like the second verse, the two are completely different rhythmically and melodically. The ‘all about that bass’ line is a chorus, but really it functions as a breakdown chorus every time. The most traditional part of the song is the pre-chorus. So the song is sort of free-form. I think it was something that was new for Meghan as a writer. As a typical song structure it is hard to do, but it might be part of the reason the song worked, because it is so unpredictable.

“I think it was Clive Davis who once said that your first verse should be a chorus, your chorus should be a chorus, your pre-chorus should be a chorus, your bridge should be a chorus, and so on. In other words, every part of the song should be memorable. That is what makes a hit song. It’s true, and I feel that it’s the case with ‘AATB’. Lyrically too, it is very memorable.

“I had put up a beat before Meghan came into the room. I did not know what kind of song we would be writing, I just thought, ‘I like this groove, and let’s see what happens.’ I had my acoustic guitar, to add chords and give things more structure, and when she came in we went through my title ideas and then it just sort of happened. We just jammed in the room. ‘All Bass No Treble’ was one of the song titles on my list, and I knew that bass was about booty. But my thinking was that the song idea was for a male rapper or urban artist of some kind. I nevertheless mentioned the title for her, and she was like, ‘Yeah, for sure,’ and just started singing, ‘Because you know I am all about that bass,’ and I went, ‘No treble!’ We were just riffing and having fun.

“We finished the lyrics and writing the actual song in a couple of hours, and I then programmed an upright bass part, and after this she sang all her vocals to the upright bass and drums. She did the lead vocal and we cut her backgrounds right after. Everything was done very fast. I went back in later on and arranged a couple of things, but not much. What we did the day that we wrote the song is pretty much what’s on the record. I might have taken a word out here or there, and I might have edited some of her harmonies, maybe I put them on the second pre-chorus but not on the first, things like that. But they were just minor things. The essence of the song was recorded that first day. And I was really impressed with Meghan. She was seen as purely a songwriter when I met her, but on hearing her sing I was like, ‘You also need to be the artist; your voice is incredible!’

All About That Double Bass

“I programmed the double bass in Maschine. The gist of the bass is sort of a loop, but it’s not very consistent because it gets a little busier in places and there are some transitional notes to keep the rhythm going and to get from one section to another. I recorded Meghan with an AKG C12VR mic, which I think went through the Chandler LTD1 mic pre and then a Tube-Tech CL1B compressor, and then straight into the Pro Tools 192, at 48kHz/24-bit. After we laid down her vocals I added my favourite guitar, which is a Fender Custom Shop Telecaster. I played it through an At Mars Specialist head into a Mojotone 1x12 with a Scumback M65 speaker, and recorded that with a Shure SM57, going into a Classic API VP28 mic pre, no compression. I used a Lightfoot Labs Goatkeeper pedal to get the tremolo effect that I was after.

“My next step was to send the session to a buddy of mine, Dave Baron, who lives in New York, and regularly works with Lenny Kravitz. I have an exchange with him: when he needs me to play guitar or sing on something, he sends his sessions to me, and when I need someone to play keyboards or program things I send them to him. We just send the song and the other person arranges as he sees fit. In the case of ‘All About That Bass’ I asked him to add keyboards and sax, and he sent me back B3 organ, piano and baritone sax parts. He played through the entire song, and I chopped and rearranged his parts the way I wanted, but his original inspiration is still there. I wanted the song to build, so until the vocals come in it is essentially just drums and bass, and then the Tele enters, and still later the piano and baritone sax, and finally towards the end the organ.

“The final mix did not take long, because I mix while tracking. When overdubbing I want people to play or sing to what sounds like a finished record. I want them to be inspired by what comes out of their headphones. So I get the sounds I want and add EQ and effects as I go, and that seems to work well. The thing that is important is to know when the record is done and to stop adding stuff. When I feel that there’s nothing more to add, the final mix is more a refinement than a final stage in itself. I may filter some low end out that I had not done before, or add some multi-band compression on some stuff. It depends on the kind of music that I am doing. This song was very easy to mix, because there’s so little musical information in it. It’s not like I have 80 background vocals and 15 pairs of guitars or keyboards!”

Nuthin’ Fancy

As Kevin Kadish indicates, the ‘All About That Bass’ Pro Tools session is nothing if not simple. At the top of the Edit window is an effects track with a vocal sample, followed by 13 drum tracks, which are bussed to one drum master track. The ‘music’ tracks consist of upright bass, baritone sax, piano, organ and Telecaster: five in total. In addition there are four lead vocal tracks and 10 backing vocal tracks, bringing the grand total of audio tracks to 33. Not the most Spartan session that has ever made an appearance in the Inside Track series, but certainly economical! Below the audio tracks are master tracks for the backing vocals, for all Dave Baron’s material (DBU), two aux tracks, a master track and an output track. Going from top to bottom through the session, Kevin Kadish reveals all the sweaty details:

The complete Pro Tools session for ‘All About That Bass’. Drum parts are at the top, followed by an audio render of the all-important upright bass track, the other pitched instruments, then the four lead vocal tracks and, finally, vocal harmonies.

The complete Pro Tools session for ‘All About That Bass’. Drum parts are at the top, followed by an audio render of the all-important upright bass track, the other pitched instruments, then the four lead vocal tracks and, finally, vocal harmonies.“The first thing I did when I got to the mixing stage was to burn all the MIDI tracks to audio. After that I got my level on the drums as a whole, and ran them through a stereo bus, with a bit of EQ from the Metric Halo Channel Strip and some distortion from the SoundToys Decapitator, to make the drums a bit edgier and dirtier. It gave the drums some extra punch. Because I had been mixing while recording, the levels were kind of there already. If an outside mixer had received this track, he’d have gone through the tracks one by one, starting with the drums and then adding instruments one by one. But for me the session was already 90 percent the way I wanted to hear it. My main focus during the final mix was to ride the vocals, making sure you can always hear them, and once the vocals were in a good place, I’d focus on the instruments. If there was a moment an instrument needed to shine, I’d pull it out a little bit.

“You can see in the Edit and Mix window screenshots that the Metric Halo Channel Strip and Decapitator appear a lot, they are on almost all the tracks. The Channel Strip is a really useful EQ for me. It is my main in-the-box EQ. It has a great EQ, and also compression if you need it, and side-chain and a gate. I use the Decapitator a lot because I would rather that things sound too dirty than too nice. But it gives different degrees of distortion on every track. The drum bus also has a send to the Altiverb aux track at the bottom, which was set to the Bill Putnam echo chamber in Cello Studios. In fact, I also had another Altiverb reverb set up at the bottom of the session, with an EMT 250 plate, as well as a slapback echo from the standard Pro Tools Extra Long Delay II, set to 68.58ms.

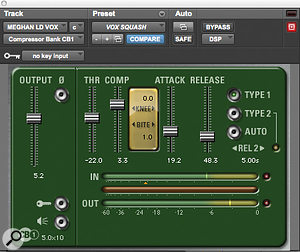

Kevin Kadish makes extensive use of the Metric Halo Channel Strip plug-in, as here on the upright bass track. “Just above the drums, right at the top, is the effects track, which is just a vocal effect, ‘bassbassbassbass’ to create some interest, which has the [McDSP] CB1 CompressorBank on it. I did that in Maschine, sampling a vocal and giving it different pitches.”

Kevin Kadish makes extensive use of the Metric Halo Channel Strip plug-in, as here on the upright bass track. “Just above the drums, right at the top, is the effects track, which is just a vocal effect, ‘bassbassbassbass’ to create some interest, which has the [McDSP] CB1 CompressorBank on it. I did that in Maschine, sampling a vocal and giving it different pitches.”

Upright Top Ranking

“Below the drums is the upright bass track, and just like the drum bus just above it, it has the Channel Strip, the Decapitator and a send to the Altiverb Putnam echo chamber. The bass is pretty much the most prominent instrument in the track. It sounds big, even though I am filtering it below 100Hz. The sample was a bit boomy and as a result the whole bass part a bit woolly below 100Hz, so I took it out. But I still had to EQ the kick drum to make space for the upright bass. It’s not only the level of the bass that makes it important in the track, but also the fact that it’s upright, which adds a lot of character. Meghan’s touring band tried to play our songs with an electric bass, and it did not work. The sound of the upright is just too distinctive, and really fits the musical direction we took. I think I used it on every song on Meghan’s album.

“The next track is the baritone sax, which has the Waves Puigchild 670, just to smooth it out a bit, and then again the Decapitator, to add some extra grit. The sax is sent to both the EMT 250 and Putnam echo chamber. Then there’s the piano, which has the Channel Strip, filtering the piano pretty high, at 500Hz, the Nomad Factory E-Retrovox set to limit mode to add some compression and character, and the Nomad E-Tube Tape Warmer, for some tape saturation. The piano is sent to the 68.58ms slapback echo and the two Altiverb reverbs. Incidentally, I just purchased some Bricasti M7 units, with the M10 controller, and I love them. They sound incredible. The next Meghan record will be Bricasti all the way! Finally, the organ has the CraneSong Dark Essence, just to darken it and take off some brashness, and the Tele has the Decapitator and the Putnam echo chamber.

As well as compression from McDSP’s Compressor Bank, Kevin Kadish used Nomad Factory’s Retro-Vox plug-in to provide additional dynamic control on Meghan Trainor’s vocal.

As well as compression from McDSP’s Compressor Bank, Kevin Kadish used Nomad Factory’s Retro-Vox plug-in to provide additional dynamic control on Meghan Trainor’s vocal. “The lead vocals are split over four tracks, and have the same effects on each, which is the Channel Strip, the Retro-Vox, the McDSP CN1 compressor, and the Decapitator. They all have the same settings, apart from the output of the Decapitator which changes a little bit. When I tracked the vocals I did not pay a lot of attention to the sound, I just used the microphone that was up, so I applied several plug-ins to improve her vocal sound. The Retro-Vox functions as a gate and the compressor catches the peaks while the Decapitator once again adds some grit. All the lead vocal tracks are sent to the slapback echo and the Putnam reverb. I didn’t treat the harmony vocals individually, but on the BV bus I had the Channel Strip, the Decapitator, and a send to the Putnam Altiverb.

“The lead vocals are split over four tracks, and have the same effects on each, which is the Channel Strip, the Retro-Vox, the McDSP CN1 compressor, and the Decapitator. They all have the same settings, apart from the output of the Decapitator which changes a little bit. When I tracked the vocals I did not pay a lot of attention to the sound, I just used the microphone that was up, so I applied several plug-ins to improve her vocal sound. The Retro-Vox functions as a gate and the compressor catches the peaks while the Decapitator once again adds some grit. All the lead vocal tracks are sent to the slapback echo and the Putnam reverb. I didn’t treat the harmony vocals individually, but on the BV bus I had the Channel Strip, the Decapitator, and a send to the Putnam Altiverb.

“At the bottom of the session is the master track, on which I have the Waves L2, bumping the level up, and after that the stereo mix goes out to my outboard SSL XLogic Gseries compressor and then my Behringer Edison EX1 Stereo Imager, both used very sparingly. When I am mixing in the box, these two units help the entire mix to feel a bit lighter and more open. After this I fed my mix back into Pro Tools and monitored through that, again with an L2, because the mix was still a bit quiet. I took the L2 off when I sent the track to mastering.”

Bad Medicine

Kadish and Trainor wrote and recorded three songs during their first set of writing sessions together, and both then went their own ways, having no inkling of what lay around the corner. Kadish began work on the second album by rock band New Medicine (released in August last year as Breaking The Model). While working on that project he received a phone call from Trainor, saying, “You need to sit down when you’re hearing this: LA Reid has just signed me because of ‘All About That Bass’, and we have to go into the studio and write an entire album!”

“So we did the rest of the album while ‘AATB’ was climbing the charts. The ‘AATB’ session was the template for maybe three or four songs on the album. But I did not want to do the same thing 11 times, so the songs are all very different, although all songs are inspired by the 1950s. Some of the songs are lusher, with a track called ‘What If I’ having live drums, recorded in my studio, and strings that are both live and programmed.”

LA Reid, who currently is chairman and CEO of Epic Records, is one of the biggest names in the American music industry, and he took one momentous decision which Kadish still admires. “There were people in Epic who asked whether our version of ‘All About That Bass’ should be sent to a top mixer or tweaked in other ways. But LA Reid just said: ‘No, don’t touch it! Just master it.’ Paul Pontius, the A&R guy, did call me and asked me whether I had any tweaks, but I said, ‘No, this is my mix.’ So it went out exactly as Meghan and I had done it during our initial writing session. That was a good call. I mean, to take a risk like that, and not feel like he had to put his thumbprint on it or micro-manage it? That’s impressive. I owe the man a nice dinner! Is the mix perfect? Technically, I don’t know. But for the song, yes, absolutely. The whole point is that it has to feel right. You can take the life out of things by over-analysing them. In any case, for me it was exciting to know that something that Meghan and I had created worked on such a big level. Particularly with this being a 1950s record, it was also very validating to have this happen after all my years of writing songs and making records. For every song you make that works there are five that don’t. And this worked in a really big way!”

LA Reid, who currently is chairman and CEO of Epic Records, is one of the biggest names in the American music industry, and he took one momentous decision which Kadish still admires. “There were people in Epic who asked whether our version of ‘All About That Bass’ should be sent to a top mixer or tweaked in other ways. But LA Reid just said: ‘No, don’t touch it! Just master it.’ Paul Pontius, the A&R guy, did call me and asked me whether I had any tweaks, but I said, ‘No, this is my mix.’ So it went out exactly as Meghan and I had done it during our initial writing session. That was a good call. I mean, to take a risk like that, and not feel like he had to put his thumbprint on it or micro-manage it? That’s impressive. I owe the man a nice dinner! Is the mix perfect? Technically, I don’t know. But for the song, yes, absolutely. The whole point is that it has to feel right. You can take the life out of things by over-analysing them. In any case, for me it was exciting to know that something that Meghan and I had created worked on such a big level. Particularly with this being a 1950s record, it was also very validating to have this happen after all my years of writing songs and making records. For every song you make that works there are five that don’t. And this worked in a really big way!”

Since the release of ‘All About That Bass,’ Trainor has enjoyed a second hit single, ‘Lips Are Movin’, and her debut album, called Title, was released in January of this year. Kadish, meanwhile, has signed a worldwide administration deal with Sony/ATV Music, and his phone hasn’t stopped ringing. We are sure to hear a lot more from these two.

No Concept, No Song

Over many years as a professional songwriter, Kevin Kadish has evolved his own methods. “I keep a list of all the ideas I get, at any point, wherever I am, which mostly consist of titles, a few lines or concepts that I think could be a good idea for a song. In some cases I also may have a melody, but for the most part they are lyrical concepts. If there’s no concept, like just a word that sounds cool, I don’t keep it. I need to know what I am writing about, what I am going to do. If you’re going on vacation you don’t just hit the highway and drive in whatever direction. You could drive for hours and still not arrive anywhere worthwhile. The destination is crucially important. These titles and concepts serve as sparks of inspiration, and they will morph into something bigger. And then the hard work comes in: they say that songwriting is five percent inspiration and 95 percent perspiration, and I think this is true.”

Why Can’t You Say That?

As mentioned in the main article, there’s quite a bit of controversy regarding the big-booty-celebrating lyrics of ‘All About That Bass’. Kevin Kadish reflects: “To me the whole idea that the song discriminates against skinny people is people totally over-thinking things. We were not being mean. We did not write the song for overweight people or to target skinny people. We wrote it for Meghan, and we did not know that she was going to get a record deal. In fact, we did not think anyone was ever going to hear the song apart from us and friends and family. We wanted the song to be funny, and fun. We just wrote it. At one point Meghan was like: ‘You can’t say that!’ And I was like: ‘Why? It is our song, why can’t we say that?’ I think it was the ‘skinny bitches’ line that she was uncomfortable about, which came from me. But I have heard skinny girls call other girls ‘skinny bitches’ — it was not meant to be mean. It was meant to be funny, and guess what, it is funny.

“Maybe some people just need to grow a sense of humour! I’m very surprised that people are more offended by the song than they are by, say, Nicki Minaj shaking her behind in a video, and literally talking about genitalia in her lyrics. I would much rather that my kids hear ‘AATB’ than some of the other things that are out there. And for Meghan it’s a great song. When I look at her I see her as the fun Ad le. I love Ad le’s music, but it’s intense. By contrast, Meghan’s stuff is light-hearted.”