If you're stuck in a creative rut with sample libraries, why not look for inspiration in your own home?

I don't think anyone except an ex-hardware sampler manufacturer can be complaining about the now-almost-total move of sampling from stand-alone, rackmount devices to computers and software. It's not just the huge amounts of cheap hard disk space and RAM that make this a good thing for samplists: the tight integration with music-creation applications has become one of those 'can't do without' technologies.

I don't think anyone except an ex-hardware sampler manufacturer can be complaining about the now-almost-total move of sampling from stand-alone, rackmount devices to computers and software. It's not just the huge amounts of cheap hard disk space and RAM that make this a good thing for samplists: the tight integration with music-creation applications has become one of those 'can't do without' technologies.

There is a flip side, though, which stems from the fact that most software samplers double up as sample players. This, coupled with the wide availability of sample CDs, means that many people fail to explore the potential of their sampler. In fact, it sometimes seems as though nobody creates their own samples any more — and if you know a handful of sample CDs reasonably well, or even the loop library of popular music software, it is quite easy to spot them being used in commercial music, TV show background music and so on. Against this background, the originality of your own samples can bring great satisfaction: it really is worth the effort.

Steve Howell's epic seven-part series ('The Lost Art of Sampling', SOS August 2005 to February 2006) was something of an eye opener and is well worth a read. It reminds those of us who have become lazy, or who never thought sampling was a viable option, that there might be some point in getting back in the groove.

While there might not be much opportunity for most SOS readers to record full orchestral sample libraries with multiple-velocity samples for every note of every instrument, there's still lots we can do with what we might have to hand. Even if you don't have a big (or even small) collection of your own instruments, a little lateral thinking can turn the world you live in into a library of sounds that absolutely no-one else will possess. You just need to open your eyes — and ears.

When Inspiration Strikes

With me, it always starts with a striking sound or rhythm: non-musical, electrical goods, such as breadmakers and washing machines; doors slamming in reverberant or resonant spaces; a child's toy that has a grown-up sound when heard out of context. The eerie, musical, water drips in the downstairs men's loo at SOS Towers... I find it pays to have a portable recording device with me at all times!

Anything that produces a rhythmic sound is a candidate for sampling. This bread maker, for example, is hypnotically rhythmic.But for a start, let's focus on our living space. We're surrounded by things that make rhythmic noise, or can be hit, or otherwise coaxed, into audible life. A door slam may well be just a door slam, but one of your doors will not sound exactly like anyone else's. Much of what we'll find in our house or flat will fall largely into two categories: percussive hits or interesting loops (which may be rhythmic or simply textural). But be open-minded and think critically; listen to how things sound in your hall and rooms, and try to hear everything in terms of the noise it makes (as opposed to the noise you think it makes).

Anything that produces a rhythmic sound is a candidate for sampling. This bread maker, for example, is hypnotically rhythmic.But for a start, let's focus on our living space. We're surrounded by things that make rhythmic noise, or can be hit, or otherwise coaxed, into audible life. A door slam may well be just a door slam, but one of your doors will not sound exactly like anyone else's. Much of what we'll find in our house or flat will fall largely into two categories: percussive hits or interesting loops (which may be rhythmic or simply textural). But be open-minded and think critically; listen to how things sound in your hall and rooms, and try to hear everything in terms of the noise it makes (as opposed to the noise you think it makes).

Of course, once sampled, any sound can be 'played' — so any thump, squeak or scrape you've recorded may well become a cool bass sound or something that does great arpeggios. You just need to figure out what its dominant pitch is and tune the sample accordingly (and if that's daunting you, see the more in-depth explanation elsewhere in this article).

If you're ready to start, examine your space and spend some time listening and, if necessary, hitting. What whiteware do you have? What size are the rooms? Do you have kids' toys? (If you don't, charity shops and car-boot sales can be a great source of sound-makers.)

Top Gear

Before you start, you need to be tooled up and ready to get to work. There are some great gadgets around, but as we're looking for sounds to mangle, you don't necessarily need 'the best'. A mic, obviously, is required, and a boom mic stand will save your arm, reduce unwanted noise and give you greater flexibility in positioning the mic. My own location mic is a bit eccentric: an older, rather battered, Audio-Technica AT9450 — a single-point, stereo condenser (not quite a shotgun!) that's intended for use with camcorders. Familiarity and a fresh battery allow me to keep noise (handling and otherwise) at bay, and the mic produces open and natural recordings with a real 'in your ear' feel... well, in my ear, anyway.

It's easy to go overboard on recording gear, but the main need is to keep things simple and portable. A Minidisc recorder, a camcorder mic and a set of closed-back headphones may be enough.Which mic to use is entirely up to you, but the fancier the mic, the more care you'll need to take and the more gear, such as PSUs, you may need to drag around.

It's easy to go overboard on recording gear, but the main need is to keep things simple and portable. A Minidisc recorder, a camcorder mic and a set of closed-back headphones may be enough.Which mic to use is entirely up to you, but the fancier the mic, the more care you'll need to take and the more gear, such as PSUs, you may need to drag around.

The recording medium can make a big difference to your workflow. You could record direct to your computer's hard drive, especially if you use a laptop or have a long lead (and remember that even quiet laptops produce some unwanted noise), but a smaller, secondary device will be less fiddly and more portable. For example, I use my trusty old Sony Minidisc recorder: I know it well, and it produces pretty good results, though if I was starting from scratch I'd probably opt for a solid-state recorder such as Edirol's R09, M-Audio's Microtrack, or Zoom's H2 or H4. Such machines produce no mechanical noise, can record uncompressed, 24-bit audio, and can generally accommodate 4GB SD cards, which is more than enough storage for this sort of work. Some include decent built-in mics, and those with USB connections also allow for fast and convenient transfer to your computer. But most of you will already have something you can record with — so use what you have, and focus your energies on the task in hand.

One last, crucial piece of equipment you'll need while recording is a notepad. Log everything you do, together with track numbers if your recorder uses them. It may sound laborious, but this simple (not to mention cheap) mechanism will be invaluable when editing your recordings into something useable. If you can be organised enough, make notes of mic position and anything else that might have a bearing on the sound as well, because if you did something good, you'll almost certainly want to remember what it was.

Starter's Orders

If you haven't headed off to start recording already, now is the time to get going. There are no rules, but you'll soon discover that mic position (proximity to the thing being recorded, how on- or off-axis the mic is, and so on) can have a dramatic effect on your recording, just like it can on real instrument and voice recording, except that here there is no right or wrong. You'll find that some positions are less noisy, and some have more presence, or simply sound 'right' — in which case use them. If you hear something that's unpleasantly boomy, harsh or whatever, then just try again until you find something better.

Though recording itself is a straightforward process, there will be plenty of noise issues to deal with. There are lots of noises inside the house that you often don't consciously tune in to, such as ticking clocks, humming boilers and fridges (which are just plain noisy, and can also add little spikes to the electricity supply, that manifest themselves as clicks in the wrong situation). Switch them off. Just don't forget to switch them back on again when you've finished! Also, your house is unlikely to be fully soundproofed, so beware of next door's TV, delivery vans reversing in the street, aircraft, noisy children outside, the vacuum cleaner in the flat upstairs and, in my case, bloody cicadas. They're a 24-hour threat where I live, especially in summer, and as for 36-hour rainstorms pummelling a tin roof, well, I'll leave that to your imagination...).

It was impossible to separate the noise-making elements of this little fella: all sorts of things engage when he's powered up, interrupted by regular yelping!Mic positioning and baffles can help to reduce some background noises, and often something as simple as picking the right time of day to record will keep unwanted ambience off your recordings (this doesn't work with cicadas...). Understanding your mic can also help, as you can take advantage of its directional characteristics. All mics, for example, even omnis, have at least some directional bias, and if you're using a cardioid mic you need to consider the proximity effect (whether you want to use it or avoid it). Also be prepared to improvise cowls and baffles with bits of cardboard, pillows and whatever else you have around you. For example, a combination of a duvet and a clothes-airer can create a nice, dead space for your mic. Just make sure it is stable: a quilt collapsing around your only mic is not worth contemplating (though, there is the potential to produce a cool, unique new sound...).

It was impossible to separate the noise-making elements of this little fella: all sorts of things engage when he's powered up, interrupted by regular yelping!Mic positioning and baffles can help to reduce some background noises, and often something as simple as picking the right time of day to record will keep unwanted ambience off your recordings (this doesn't work with cicadas...). Understanding your mic can also help, as you can take advantage of its directional characteristics. All mics, for example, even omnis, have at least some directional bias, and if you're using a cardioid mic you need to consider the proximity effect (whether you want to use it or avoid it). Also be prepared to improvise cowls and baffles with bits of cardboard, pillows and whatever else you have around you. For example, a combination of a duvet and a clothes-airer can create a nice, dead space for your mic. Just make sure it is stable: a quilt collapsing around your only mic is not worth contemplating (though, there is the potential to produce a cool, unique new sound...).

As well as sound travelling through the air, you need to think about mechanical vibration. I've had to deal with unsteady washing machines (the kind that are a bit unbalanced and jump around, creating vibrations in the floor that transfer up the mic stand). A makeshift solution that enabled me to get a good recording was to grab the thick foam base cushion from the sofa and stick the mic stand on that.

When working with small items, where you're essentially recording your own 'performance', remember that it is easy for you to become the source of unwanted noise. If you're able to wear headphones while recording (remember to use closed-back headphones, otherwise the headphones themselves can become the source of noise), you'll be aware of any you-generated noises right away, and get advance warning of distortion or overloads, even if your eyes are not on your recorder's meters.

Sources of such noise, and techniques for reducing it, are fairly common-sense, but it is worth running through the basics. Place the mic stand so that you have plenty of space to move around the item being recorded, especially if it involves you hitting the item. You want to make the recording without accidentally thumping your mic, tripping over the lead or nudging the mic stand. Also beware of breathing and lip smacks, particularly if your mic is sensitive and omnidirectional. If this is causing problems, take a lungful of air, hold it and only move enough to create the sound. Then let go once the sound has been recorded (this point is especially worth remembering!).

Don't be averse to using a recorder's automatic gain-control option if time is short, or the metering is inadequate (as on my MiniDisc recorder), though if it's a developing sound that varies widely in volume, it is better to use a manual setting (perhaps recording at a lower level and normalising later). The modern 24-bit recorders are particularly good for this, as they allow you to capture a healthy signal while leaving plenty of headroom.

Bearing the above in mind, it is fairly easy to gather satisfying sounds. My personal exploration when preparing this article revealed rhythms and hits from a washing machine, breadmaker, dishwasher, fireplace guard, infant's xylophone and tambourine, doors slamming (both close-miked and with a hall's worth of reverb), and banging the lounge floor above the garage.

Acting On Impulse

One application for sampling that has only recently arisen (and even more recently become affordable for most of us) is the creation of impulses for use in convolution processors. Cakewalk's Sonar 6 Producer Edition comes bundled with a beauty — the Perfect Space convolution reverb, 'powered by' Voxengo, though if you don't have this there are now plenty of commercial and freeware alternatives. Essentially, these plug-ins take an audio file (the impulse) and use it to generate a reverb, based on the interaction between the impulse and the audio being processed. This is most commonly used to create realistic sounding reverbs, but loading more off-the-wall samples in place of reverb impulses can yield interesting results. For example, I placed a mic inside various bowls, vases and other vessels and recorded the clangs from resonant items, using the results as impulses. My favourite involved striking a 70cm Swiss Ball. From the inception of convolution I've wanted to figure out how to get a mic inside one of these to record an impulse but I actually found that I didn't need to: just the sound of it hitting the floor, trimmed a little, provided the effect I'd been looking for.

Editing

You can easily end up with hours of audio, so remember, when you're recording, that at some point it will all need to be transfered and edited. If you recorded direct to a computer, you get to skip a step. If you recorded to a USB device, you just need to drag the audio files to your computer for editing. With an older system like mine, you will probably need to record the output from the recording device to your hard drive. Though this process can seem tedious it has its advantages: I take the opportunity presented by the transfer stage to audition and capture audio 'on the fly' as the good stuff appears, which saves me a lot of bother later. It also avoids clogging up my hard drive with unwanted fluffs, breaths and cicadas.

Recording this space (my garage) contributed to my second-favourite kick drum sound ever... I won't bore you with the story of my favourite!The software you use to sample and/or edit is up to you. Personally, I'm quite a fan of open source and free software at the moment, and do a lot of my work in the cross-platform Audacity (http://audacity.sourceforge.net/). For acquisition, though (getting the audio into the computer) I use the free version of NCH Swift Sound's PC-only Wave Pad (www.nch.com.au) because it has a 'smart' record option that only records when audio is present. If you have better-specified commercial tools on your system that you know well, they will probably suit you better. Not being able to create any kind of sustain loop, for example, let alone a crossfade loop, with Audacity is a bit of a hindrance (I overcome this by creating long samples: find a section of a sample that would loop if the option were available and make multiple copies at the end of the sample).

Recording this space (my garage) contributed to my second-favourite kick drum sound ever... I won't bore you with the story of my favourite!The software you use to sample and/or edit is up to you. Personally, I'm quite a fan of open source and free software at the moment, and do a lot of my work in the cross-platform Audacity (http://audacity.sourceforge.net/). For acquisition, though (getting the audio into the computer) I use the free version of NCH Swift Sound's PC-only Wave Pad (www.nch.com.au) because it has a 'smart' record option that only records when audio is present. If you have better-specified commercial tools on your system that you know well, they will probably suit you better. Not being able to create any kind of sustain loop, for example, let alone a crossfade loop, with Audacity is a bit of a hindrance (I overcome this by creating long samples: find a section of a sample that would loop if the option were available and make multiple copies at the end of the sample).

After the initial editing, I tend to do most of my work in Reason. In fact, all my sample editing is biased towards that environment: my rhythmic loops all get processed by Propellerhead's ReCycle, to produce the files played by the Dr Rex device. Don't wory if you don't have Reason, as there are plenty of alternatives for rhythmic processing. For example, Sony's Acid (a free Xpress version is available at www.sonycreativesoftware.com) works well on the PC; and the Apple Loops Utility is available to users of some Apple software. There are plenty of other options, like Ableton Live, but if you're reading this, I imagine that you'll already have something that's capable of doing the job.

It is often easiest to select audio that works to full bar lengths. Play the audio and tap along with it to see what 'time signature' it has, and what the recurring pattern is. Sample more than you need either side of the pattern you want to keep, then fine-tune it in your sample editor and set the audio to loop, to make sure the tempo and 'beat' aren't compromised. This means listening out for discontinuities and jarring loop turnarounds where the sample is too long or too short.

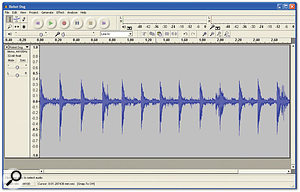

These three screenshots show my workflow for editing rhythmic parts. In this case, I brought a sample (courtesy of that cute robot dog walking and barking in a regular cycle) that looked like good loop material into Audacity (above left) for editing. My next step for loop manipulation was Propellerheads' ReCycle (above). The dog is not in any way 'regular', but the selected pattern lasted for a little over one bar and three beats. ReCycle's grid didn't help much, due to the sample's irregularity, but the peaks were so obvious that placing the slices manually was easy. Finally, I loaded the resulting file (which turned out to be one bar and three-and-a-half-beats long) into Reason's Dr Rex (left) and used a little quantisation to put the loop in time with anything I decided to add later.Once it's the right length, a sample can be imported into ReCycle, or the tool of your choice. Tell the software how many bars you think the audio is, manipulate the slicing tools as usual, and you should get something sliced up that will now play back at any tempo. Of course, if the pattern is a little uneven or goes against the beat, though still fitting within an overall number of bars in your selected time signature, you may have to move slice markers around to make it play back correctly. Certainly, in Reason, REX loops played back in Dr Rex can easily be quantised if you want the off-beat to become more regular. If the slice markers are at the right parts of the audio file, all will be well.

These three screenshots show my workflow for editing rhythmic parts. In this case, I brought a sample (courtesy of that cute robot dog walking and barking in a regular cycle) that looked like good loop material into Audacity (above left) for editing. My next step for loop manipulation was Propellerheads' ReCycle (above). The dog is not in any way 'regular', but the selected pattern lasted for a little over one bar and three beats. ReCycle's grid didn't help much, due to the sample's irregularity, but the peaks were so obvious that placing the slices manually was easy. Finally, I loaded the resulting file (which turned out to be one bar and three-and-a-half-beats long) into Reason's Dr Rex (left) and used a little quantisation to put the loop in time with anything I decided to add later.Once it's the right length, a sample can be imported into ReCycle, or the tool of your choice. Tell the software how many bars you think the audio is, manipulate the slicing tools as usual, and you should get something sliced up that will now play back at any tempo. Of course, if the pattern is a little uneven or goes against the beat, though still fitting within an overall number of bars in your selected time signature, you may have to move slice markers around to make it play back correctly. Certainly, in Reason, REX loops played back in Dr Rex can easily be quantised if you want the off-beat to become more regular. If the slice markers are at the right parts of the audio file, all will be well.

Working with single hits is an easier process: just go through your audio till you hear something you like and sample it! A little fine-tuning may be necessary: a fade applied to the end of the sample, normalisation, that sort of thing (and don't forget wht I said earlier about working with pitch).

Continue to listen critically through the sampling and editing process. Try to imagine how sounds might sound when shifted an octave up or down, and if you can't imagine it, just try it and see — the 'undo' function is one of the great benefits of software! Your critical listening should reveal parts of sounds that are desirable. Let's take an example. Sampling machines and metal in resonant spaces will inevitably produce fading tails that have a definite pitch, so try chopping out the main sound and normalising the fade: it could be a great bass sample providing an interesting waveform starting-point for synthesis.

Once edited, you'll need to name your samples, and it helps if you can be sensible — avoiding the sample file equivalent of 'Doodle 1', for example. For future reference, on at least the basic first run of samples try to provide names that remind you of the original source, and perhaps compile related samples into folders or libraries. It is also a good idea to note in the name any pitch-shifting or filtering that you might have applied.

Most importantly of all, load the samples into something you can get creative with. Perhaps all you'll have is another load of drum kits, but that's fine: the chances are that you'll have a range of textures and loops that sound familiar to you, but spark off tracks that you wouldn't have arrived at in any other way.

Conclusion

So why go to all this bother? Well, the penny should have dropped several paragraphs ago.

I discovered what was, for me, one of the biggest, most solid kick-drum sounds ever by sticking my mic in the garage and stomping on the lounge floor (which is directly above). My washing machine filling up produced a water sound that would be perfect for certain types of ambient music — it sounds wet and unreal, but not mechanical. It was a shock to discover a child's tiny xylophone was a quarter-tone off concert pitch, but it's a great sound and worth the effort of a small amount of tuning.

In short, you are surrounded by sounds that can be inspiring, so keep your ears open and record what's around you, and I promise that you'll come up with something fresh and new (which, after all, is what most people want from their music). If you gain a deeper understanding of your software tools, they can help you get the most out of your raw material. So if you have invested in something like Halion, Kontakt or EXS24, don't settle for playing back someone else's sounds all of the time — delve a little deeper. There's a whole world around you beyond the house: you could move onto traffic, power tools, sports equipment... you get the picture. Now, go forth and sample!

Making Your Pitch

Working out the dominant pitch of a sample is reasonably straightforward. You can, of course, go for a pitch-detection routine, such as is built into many audio programmes. But one quick method I use is to load an 'unpitched' sample into Reason's NN19 sampler and trigger it with a very simple Matrix sequencer pattern, while also triggering a Subtractor synth from the same pattern (using a Spider CV splitter device to make the connection between the Matrix and the two sound-making devices). I then listen closely, while tweaking the root pitch and other tuning parameters of the sample in NN19 as the pattern loops, using the Subtractor as a reference until it sounds right (be prepared to tweak the Subtractor's octave settings if necessary). Although I've used Reason here, similar strategies should work in other environments.

It often helps to play the hit outside its normal register: it becomes easier to hear the central pitch of a low-frequency sample, for example, if you shift it up an octave or two. Get the fine-tuning right, and then re-shift it down to the correct register and continue.