Avebury Henge is one of England’s most significant and best-known neolithic sites.

Avebury Henge is one of England’s most significant and best-known neolithic sites.

His quest to capture the spirit of Avebury led former Radiophonic Workshop composer Steve Marshall to develop some unique experimental recording techniques.

Living close to the famous Avebury stone circle in Wiltshire, I have spent many years researching and photographing its landscape and numerous prehistoric monuments, making some significant archaeological discoveries. Following a long career as a musician and composer, I then published my book Exploring Avebury: The Essential Guide in May 2016. The book proved popular, so I found myself wondering what I should do next.

To many people, Avebury is about more than archaeology: it is a mystical, spiritual place. Although I’m interested in this side of Avebury, I have never felt I could write about it. Music, however, is a different matter. So instead of writing that ‘difficult second book’ I decided to make an album of electronic music where each of the 10 tracks would relate to a different monument, or some aspect of the Avebury landscape.

To many people, Avebury is about more than archaeology: it is a mystical, spiritual place. Although I’m interested in this side of Avebury, I have never felt I could write about it. Music, however, is a different matter. So instead of writing that ‘difficult second book’ I decided to make an album of electronic music where each of the 10 tracks would relate to a different monument, or some aspect of the Avebury landscape.

Out With The Old

During my years of composing music for TV I had a large studio in a barn, full of vintage electronic instruments. For 20 years I had spent all day, every day, playing a keyboard into a MIDI sequencer that controlled a large array of sound modules, all routed into an analogue mixer. Disposing of it all was a huge relief, ridding me of the nagging fear that the antique kit would spontaneously burst into flames some day! I retained a few favourite pieces of equipment: a Yamaha DX7, loved mainly for its keyboard, my trusty EMU Proteus 2000 sound module, and the Longwave Instruments Theremin that I had built into a 1920s sunburst cabinet. My prized Tannoy 18-inch Monitor Golds went, but I could not part with my JPW nearfield monitors, made by a long-defunct company in Cornwall. With a hi-fi amplifier, an old Mackie micro-mixer and my laptop, this was all the equipment I would need to produce Avebury Soundscapes.

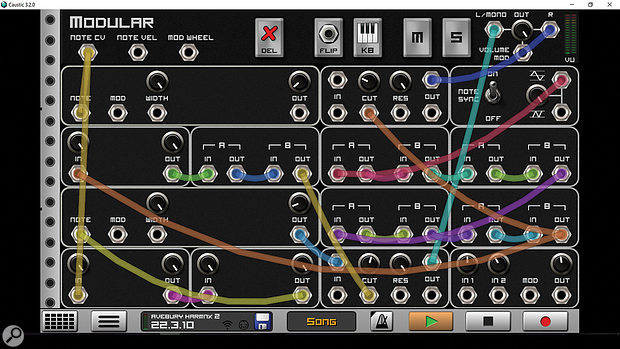

On returning to music after a few years away, I did not want to continue as I had done previously. Using a MIDI sequencer risked producing music that sounded like my old film scores, which was not what I wanted. On looking around for cheap, MIDI-less alternatives, I found that Caustic 3, an app for Android phones and tablets, was exactly what I needed. Like early versions of Reason, it has a virtual rack of synths and drum machines, controlled by step-time sequencers. It even has a modular synth, vocoder and effects, yet it costs just £5.99 and there is a free version for PC! Caustic sounds superb and is easy to operate; it comes with an excellent library of sounds that can be endlessly tweaked, with automation of all parameters. Songs created in Caustic may be exported as stems.

Who needs Eurorack when a £5.99 app can do the job?

Who needs Eurorack when a £5.99 app can do the job?

Caustic’s beatbox library includes classics such as the Roland 909, 808 and 606. I am particularly fond of those machines, having once owned the originals, and they provided most of the drum sounds for the album. The sampler in Caustic is very similar to the range of hardware Akai machines that I previously used. It plays WAV files, so I was quickly able to set up groups of sounds from my own library. The Caustic modular synth is particularly good and I spent many happy hours modifying the presets and creating new sounds from scratch. Much of the Caustic programming for the album was done on my smartphone or tablet whilst travelling on buses, trains and planes. I then transferred the songs to the PC version of Caustic on my laptop, to work on them further.

Audacious Decisions

For the album, I intended to also include binaural field recordings I had made around Avebury over many years. These would have to be edited and processed, but I didn’t want to get involved with DAWs again. After considering several of the many options available I chose Audacity, a popular open-source sound recording and editing application that is completely free. Although far from perfect, Audacity was ideal for my purpose since it is highly tolerant of different word lengths and sample frequencies: virtually any digital recording can be dragged and dropped into Audacity and it will play instantly. Many studios use Audacity just for format conversion, but it also offers some excellent effects and can be used as a simple multitrack DAW. Like Caustic, Audacity easily exports all its recorded tracks as stems that can later be transferred to a more sophisticated package such as Pro Tools.

Rather than using a mainstream DAW, Steve relied on the freeware Audacity.

Rather than using a mainstream DAW, Steve relied on the freeware Audacity.

Most of my sound sources for the album were either in software or already on my hard drives, but I still needed to record more. Having disposed of all my studio mics, I discovered that my tiny Zoom H1 was quite adequate instead. Recording at 24-bit gave me enormous headroom, and any latent noise could easily be removed in Audacity. There was also more binaural recording to be done, and for this I used my home-built binaural rig: a pair of modified tie-clip mics connected to the line input of the Zoom H1.

Before the project began I had conferred with Nick Beere, whose Mooncalf studio is close to Avebury, in a rural location overlooking the Marlborough Downs. Nick would be handling the final mixes, using his Pro Tools HD system with Dynaudio monitors and a subwoofer. My project was intended for CD, and possibly vinyl, so we chose to work at 44.1kHz and 32-bit.

Immersive Sound

Binaural recording still continues to fascinate me, even after I’ve been experimenting with it for over 30 years. I have made dozens of ‘dummy heads’ in that time, producing recordings that are startlingly three-dimensional, with sound appearing to come from all around, above and below the head of a listener wearing headphones. Some 10 years ago I made an album called Bilocation which used my own system of phase cancellation to convert binaural recordings into 5.1 surround sound. Sadly, properly set up domestic surround sound is still uncommon today, but headphone listening is more widespread than ever, making it quite feasible to include binaural recordings in an album. For Avebury Soundscapes, rather than use a dummy head, I recorded with tiny electret mics mounted in my ears. This produces excellent spatial imaging, but for health and safety reasons I cannot recommend that you try it!

Avebury Soundscapes begins with ‘First Light’, a musical impression of the many dawn visits I made to Avebury photographing misty sunrises for my book. It features the sound of startled birds, flapping out of the trees. Binaurally recorded, these are uncannily realistic, appearing to be quite clearly overhead. ‘River Of Souls’ begins with an overhead binaural thunderstorm that is equally impressive.

Several of Avebury’s prehistoric monuments are circular, and circularity was something I wanted to explore sonically, using binaural recording. The track ‘Great Circle’ portrays the Avebury Henge, an earthwork and stone circle a quarter of a mile across. It features a technique I first tried some 30 years ago, of playing sounds through rotating speakers and re-recording them binaurally. From two three-metre lengths of timber, I made a cross, which was then suspended on a rope from the ceiling of my garage, so that the cross could spin horizontally like a carousel, about two metres above the floor. Domestic hi-fi speakers were attached to the four ends of the cross. With the cross turning, sounds were played through the speakers and re-recorded binaurally. Though laughably simple, this produced spectacular results: when played back on headphones, the re-recorded sounds appear to rotate around the listener’s head.

This home-made carousel, consisting of four hi-fi speakers suspended from a rotating cross, was used to make sound appear to be rotating about a listener. The effect was recorded on binaural in-ear microphones.

This home-made carousel, consisting of four hi-fi speakers suspended from a rotating cross, was used to make sound appear to be rotating about a listener. The effect was recorded on binaural in-ear microphones.

Upwardly Mobile

Silbury Hill is a massive man-made conical earthwork near Avebury.Silbury Hill is an immense artificial mound near Avebury, constructed around 2400BC. Enough chalk to fill 1.3 million wheelie bins was piled up, layer upon layer, to a height of 30 metres, in what was likely a festive annual event for the whole community. To create an impression of Silbury growing upwards I used an effect known as a barber pole — a sound that rises ever upwards, like its namesake.

Silbury Hill is a massive man-made conical earthwork near Avebury.Silbury Hill is an immense artificial mound near Avebury, constructed around 2400BC. Enough chalk to fill 1.3 million wheelie bins was piled up, layer upon layer, to a height of 30 metres, in what was likely a festive annual event for the whole community. To create an impression of Silbury growing upwards I used an effect known as a barber pole — a sound that rises ever upwards, like its namesake.

To make a barber pole, begin with a sound several seconds long that rises smoothly in pitch. At its simplest this could be a single note, played with pitch-bend on a synthesizer, but it is more interesting to use a constant natural sound such as bubbling water. Audacity has a useful Sliding Time Scale/Pitch Shift function that is ideal for this, allowing the sound to be slowed down or speeded up as if it was on analogue tape. I would typically process a sound to begin at -50 percent and rise to 200 percent of its original speed. After pitch-shifting, the sound must be faded in at its start and faded out at its end, then looped by copying it many times onto the first track of a DAW. This looped sound can then be copied to the next track and shifted to start, say, one second later. Copy it again to another track and delay by a further second, then continue likewise on further tracks. This eventually produces a barber pole, an eerie effect that would be difficult to achieve any other way. My album track ‘Silbury Rises’ features a large assortment of barber poles, all made with different sounds. These were further processed by playing them through the rotating speakers of my ‘carousel’ and re-recording them binaurally.

Off The Beaten Track

Some of Mark Ty-Wharton’s weird and wonderful electronic instruments.Making music is always better with some form of collaboration, so I was fortunate to get help from Mark Ty-Wharton, who runs a fabulously eccentric music shop called Sonus Magus in Glastonbury. Mark builds and sells strange and bizarre instruments of his own design, often housed in rusty old tins or wooden boxes; some are bare circuit boards. The sounds they produce are extraordinary, reminiscent of the days when synthesizers were commonly played without a keyboard, like the VCS3. Mark took some early demos of my album tracks and produced a variety of weird and inspiring sounds to go with them. Some were used as Mark intended; others I cut up, processed, and used on a different track altogether.

Some of Mark Ty-Wharton’s weird and wonderful electronic instruments.Making music is always better with some form of collaboration, so I was fortunate to get help from Mark Ty-Wharton, who runs a fabulously eccentric music shop called Sonus Magus in Glastonbury. Mark builds and sells strange and bizarre instruments of his own design, often housed in rusty old tins or wooden boxes; some are bare circuit boards. The sounds they produce are extraordinary, reminiscent of the days when synthesizers were commonly played without a keyboard, like the VCS3. Mark took some early demos of my album tracks and produced a variety of weird and inspiring sounds to go with them. Some were used as Mark intended; others I cut up, processed, and used on a different track altogether.

Not all of my own sounds came from Caustic: I also used my Proteus 2000 and Theremin. Ever since I bought it in about 1990, I have practised my Theremin technique about once a year, whether I needed to or not. For ‘First Light’ I wanted a very particular sound: four Theremins playing a sequence of chords, together in four-part harmony. Each note of the chords was to begin with a huge, upward pitch glide of several octaves. This would be fiendishly difficult for even the best player: for me, it would be impossible. The solution was to resort to studio technique — and cheat. I recorded the parts backwards, one at a time. With a guide synth playing my target note, I matched its pitch with the Theremin, then slipped rapidly down in pitch. When reversed, this produced exactly the desired effect. Another track, ‘Palisades’, features a solo Theremin and yet more cheating. This time I recorded the part at Mooncalf, where Nick Beere used Auto-Tune to correct my dodgy technique. Perfect!

The West Kennet Long Barrow, inspiration for ‘Bone Ceremony’ and source of impulse responses...My favourite track on the album is probably ‘Bone Ceremony’, an imaginary Neolithic ritual in the West Kennet long barrow. Some of the musical elements were recorded in the actual stone chambers of the monument; others were processed with convolution reverb in Audacity and in Pro Tools. Samples of balloon pops recorded inside the barrow were used to recreate its ambience. Amazingly, convolution samples that are recorded binaurally will produce 3D ambience!

The West Kennet Long Barrow, inspiration for ‘Bone Ceremony’ and source of impulse responses...My favourite track on the album is probably ‘Bone Ceremony’, an imaginary Neolithic ritual in the West Kennet long barrow. Some of the musical elements were recorded in the actual stone chambers of the monument; others were processed with convolution reverb in Audacity and in Pro Tools. Samples of balloon pops recorded inside the barrow were used to recreate its ambience. Amazingly, convolution samples that are recorded binaurally will produce 3D ambience!

...which were added to other sounds using the freeware SIR convolution plug-in.The climax of ‘Bone Ceremony’ is the magical and rather sci-fi appearance of four ghosts — ancestral spirits conjured down by the ritual. The ghosts arrive one at a time, preceded by a whooshing noise that rapidly descends from overhead. To do this, I used some binaural recordings I had made of rockets taking off; surprisingly, when played backwards, their spatial effect is preserved. Each ghost then announces itself, their voices treated with pre-echo. The raw vocals were played backwards, echo was added, then the recording was reversed again. This produces an eerie effect of echoes that precede their source. Finally, the ghosts morph into a flock of rooks and return up to the sky.

...which were added to other sounds using the freeware SIR convolution plug-in.The climax of ‘Bone Ceremony’ is the magical and rather sci-fi appearance of four ghosts — ancestral spirits conjured down by the ritual. The ghosts arrive one at a time, preceded by a whooshing noise that rapidly descends from overhead. To do this, I used some binaural recordings I had made of rockets taking off; surprisingly, when played backwards, their spatial effect is preserved. Each ghost then announces itself, their voices treated with pre-echo. The raw vocals were played backwards, echo was added, then the recording was reversed again. This produces an eerie effect of echoes that precede their source. Finally, the ghosts morph into a flock of rooks and return up to the sky.

After spending about six months working on the project at home, I took the exported stems from Audacity and Caustic to Nick Beere to be mixed at Mooncalf. I thought what I had was good, but Nick took it to a whole other level! Not only were the sounds improved, but having input from another musician made an enormous difference. We spent seven thoroughly enjoyable but exhausting days mixing the tracks. The finished mixes were then arranged in running order and passed on to Nick Robbins, a world-class mastering engineer. Nick made some “slight adjustments”, as he put it, to levels and EQ that turned a diverse collection of great mixes into a coherent whole: a truly professional-sounding album that belies its origins in a £5.99 phone app!

Avebury Soundscapes is available as a CD or download from Bandcamp: https://aveburysoundscapes.bandcamp.com/album/avebury-soundscapes.

Perfect Harmonies

Many people regard Avebury as a sacred and mystical place, but how can that be expressed musically? To me, the most mystical element in music is the harmonic series, and so harmonics feature heavily throughout the album, in several different forms. One is overtone singing, which I have practised for many years. By singing a drone and changing the shape of one’s mouth, individual harmonics can be amplified and even used to play a simple tune. You are, in effect, singing two notes at once: the harmonic tune and the drone that underlies it. I also produced several different harmonic sweeps using the modular synthesizer in Caustic. The first few steps of the harmonic series equate to musical intervals — the octave, fifth, third and so on — so can easily be played on a keyboard. I spent a great deal of time programming rhythmic patterns of harmonics in Caustic.

Most of the sounds used on the album were purely electronic, but I also used some rather special metal windchimes. Garry Kvistad in the USA is an expert percussionist who has played with Steve Reich for over 30 years, and is also the founder of Woodstock Chimes, a highly successful company based in Woodstock, NY. Garry’s chimes are special because they are perfectly tuned in ‘just intonation’, an ancient system based on harmonics. For one track, ‘River Of Souls’, I recorded four different sets of chimes, which all sound beautiful when played together because their harmonics are aligned. This is particularly obvious when the recordings are slowed down to half speed: the chimes sound rather like a Javanese gamelan orchestra.

Garry Kvistad explains his tuning system in an interview for Fortean Times: www.stevemarshall.org.uk/docs/Chiming_in.pdf.

Further Reading

- Steve Marshall’s account of his time spent as a composer in the BBC Radiophonic Workshop:

www.soundonsound.com/people/story-bbc-radiophonic-workshop

- Steve’s binaural recording setup is detailed in this SOS feature:

www.soundonsound.com/techniques/bilocation-binaural-recording-51-surround