Fifteen years ago,the idea that writing music for computer games could put you in the frame for a major Hollywood film‑scoring job would have seemed laughable. But it's exactly what has happened to Nathan McCree and Matt Kemp. Paul White travelled to their Oxfordshire studio to unearth more...

Nathan McCree and Matt Kemp are Meode Productions, a company formed in 1998 after the duo's success in writing and producing the music for the Tomb Raider series of computer games for Core Design. Now working from a bedroom studio on the edge of the Cotswolds, the team are hoping to write the score for the new Paramount Tomb Raider movie. They also have other musical directions they'd like to explore — Meode, for instance, created the intro music for the Spice Girls' Earls Court concert and subsequent UK tour.

Division of labour between the two is fluid, but in general Nathan does most of the composition, while Matt handles engineering duties and sound‑effects design. They met at school, where Nathan studied music to 'A' level. While he became bored and went to college to study computer science, Matt got a job in a studio, allowing the pair to use a year's worth of down time to work on their own material.

After college, Nathan got a job at Core Design as a computer programmer, where his first project was a musical sequencer for the Sega Megadrive. It was around this time that he showed his boss some music he'd been working on — whereupon he was asked to come up with a soundtrack for Asterix II. "That was it, a job change overnight!" explains Nathan. "At that time I had a MIDI system based around Cubase, and most of the games were CD‑based products in that they used CD audio soundtracks rather than MIDI files. I think the CD games machines came in around '94. One of the first orchestral‑style projects I did for the CD machines was for a game called Soulstar. The project manager asked me if I could do some John Williams‑type Star Wars music! I'd never written any orchestral music before, but it came up trumps and was nominated for an award."

Although the soundtrack consisted of CD audio, budgetary constraints forced Nathan to produce it in a MIDI studio: "I've never worked with an orchestra and had just a couple of synths — nothing spectacular. I had a Korg O1/W, an Ensoniq SQ1 Plus and a Roland D20. It was a bit of a bodge job, but it worked."

Meode's success has allowed them to expand their studio setup over the years, and most of their recent projects, including Tomb Raider, have been done using Roland JV‑series modules: "I got hold of a JV1080 with an Orchestra I expansion board in it, and that is brilliant. It did the bulk of the work. I've since got an Orchestra II board which is better still. I also added a JV90, which is like a keyboard version of the 1080, and I put an orchestral board into that as well.

"For sequencing, I'm now using Cubase VST on a PC. The reason for using PC rather than Mac is that the PC is the platform the games are developed on, so it gives me more chance to try things out properly. When we're working on the games, the map designers have a system that allows me to place music on certain areas of the map, and to specify certain laws that govern when they're played. Once that's done, we burn a new CD, then I can run through the levels myself to see how the tunes fit in and check that everything is working properly."

Starting Points

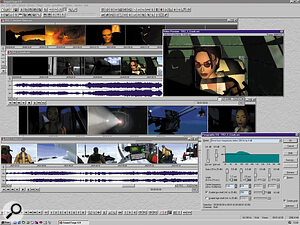

Some of Nathan and Matt's Tomb Raider music in the Arrange Page screen from Cubase VST.

Some of Nathan and Matt's Tomb Raider music in the Arrange Page screen from Cubase VST.

Like writing music for film or television, you might expect that music for computer games has to be tightly structured to fit visual cues and lengths, as well as fitting in with the style of the game. As Nathan explains, however, they are given a very free reign: "We're actually given very little at the start of a job. Most of the time I have to work from a single word. They might say they want something to go with the Jungle level of the game and you have to go away and write something that might fit in with a jungle scene. Or, they might tell me she goes on a ship at some point, and off you go again. Everyone is experimenting as they go, and nobody is really sure how the game is going to go, how the story is going to unfold or how it's going to end up. It's very much dependent on what we can get the games machine to do.

"If it's a puzzle game, you can write location music, so if somebody goes to India, you might write an Indian‑sounding piece. With something like Tomb Raider, I tend to think of it as mood music, so I'll pick a set of moods that I want the user to experience — fear, safety, aggression and so on. I'll write five to 10 pieces in each mood, then when it comes to placing them in the game, you have to hope it all fits together."

Partly because of the way in which the projects he works on evolve, Nathan has developed an unusual way of writing material in incremental stages: "I tend to concentrate on a section a few bars long, then I'll add the different instruments until that section is complete. When I've got that, I'll work around the edges by adding sections before or after what I've just written and grow the piece like that. At least that way, if somebody wants me to finish a tune quickly, it's not too much of a job to tidy it up, even if you've only got a minute of it done."

Although the music is not, and perhaps cannot be, as tightly synchronised with the visuals as in a TV programme or film, a structure usually evolves during the development of a game in which every section has its own theme. "There's no specific length and there are tunes used for atmospheres that loop after around three minutes," explains Nathan. "The actual musical parts don't loop — they describe a particular point in the game, then you move on to another section with different music. Apart from the musical soundtracks, which can be up to 100 separate tunes, there are also 10 or 15 video sequences and about the same number of atmospheres to create. On top of that, there may up to 400 sound effects."

"What we tend to do," adds Matt, "is blow a CD with all the music tracks on it, and they are called up by the program as required. They have to be in a particular order so the right one is called up when triggered within the game. The sound effects tend to get loaded in for each level of the game, so they're not stored as audio CD tracks — they're real‑time processes."

The obvious next stage in the future development of games music would be to use layered sounds to create evolving music that changes to suit the action. I asked Nathan if he'd tried this approach. "We talked about it at the beginning of Tomb Raider II when we considered doing interactive MIDI music, but we decided against it because of the inconsistent quality of MIDI playback hardware. What had impressed everyone about the original Tomb Raider was the film score orchestral sound, and it's very difficult to get that using a typical GM sound card. Using real audio recordings, you get more control over what the end user hears."

Because the CD audio they produce has to share a disc with the program code and data, Nathan and Matt have to fit their soundtracks into a fairly limited amount of space. Moreover, as Nathan explains, this is complicated by the fact that until the end of the project, they don't know how much space will actually be available: "There is a limit, but it's not given to us at the start of the project because nobody knows how much space is left for the sound until the entire game is finished. We have a rough idea in that we normally aim for about half the disc — about 300Mb. In Tomb Raider III we used XA compression, which gave us four times the playing time we would have had if the audio had been uncompressed. That was great, but Tomb Raiders I and II were a nightmare because literally a day before the release, you'd have to start cutting things out and redesigning the structure of all the music you'd written over the past three months, just so you could lose some tunes. And it's not just a case of losing a minute or two, you have to lose something like 15 minutes, which is very scary. The last week is a nightmare, and I've seen several design people have nervous breakdowns in the computer games industry!"

Working Around

The principal tool used for sound effects editing is Sonic Foundry's Sound Forge PC audio editor.

The principal tool used for sound effects editing is Sonic Foundry's Sound Forge PC audio editor.

The need to create orchestral music on a budget has forced Nathan and Matt to find ways of overcoming some of the inherent limitations of samplers and synths compared to real orchestral instruments. "It helps if you understand the instruments in the orchestra," explains Nathan. "For example, a flute player needs to breathe, so it's no good writing long passages with no breaks. You can also sample a breath and place that in the gaps, which I've done in some of my work for Core. There was a choral part where I added breathing between phrases — I sampled myself breathing eight times, then doubled that up to get the right effect."

Matt adds: "I think we improved the sound in Tomb Raider III compared to I and II, because I was able to take the responsibility for sound quality and for the placing of sound effects away from Nathan, allowing him to concentrate on writing the music. We also panned each instrument in accordance with a traditional orchestral layout relative to the conductor/listener, giving it added authenticity."

"String playing is also very important," continues Nathan, "and you have to know how the bowing works. For example, if you do a scale on one long bow stroke, it sounds quite different to playing the same line with alternating strokes. You can add life and dynamics by incorporating both types so the music progresses at different places. If you're writing a very agitated piece, you may want the bow action to be a lot quicker, whereas if it's a smooth, calming piece, you have to take that into account with your choice of string sound. Take agitato strings for example — they're great for fast runs, but terrible for long held chords. You have to pick your sounds carefully. It's not as simple as writing a string part, then moving the phrases onto tracks assigned to the right kind of string sounds — you also need to play the sounds differently. I've had as many as eight different string parts within one piece of music."

Onto The Silver Screen

Meode's studio is based around a Mackie 8‑buss analogue desk, with Yamaha NS10M and Peavey monitors.

Meode's studio is based around a Mackie 8‑buss analogue desk, with Yamaha NS10M and Peavey monitors.

Composing electronic music for a computer game is one thing, but Nathan and Matt have ambitions to expand into the hugely competitive field of film scoring, and hope to use the forthcoming film of Tomb Raider as a way in. "I kind of went after this myself, which is one of the reasons I left Core. I wanted to pursue all the things I couldn't do while fully employed. I put in a call to Lloyd Levin, the producer and when I got through to him on the phone, he was very willing to see me — it turns out he was a fan of the music from the games. So I went to LA, met him and he said he wanted me to be involved. He's now got Simon West to direct the film and Angelina Jolie has been signed on to play Lara Croft.

"I'd obviously like to record this with a real orchestra and I discussed this approach with Lloyd. The film is actually being made at Shepperton, so that's very handy for us. The budget is around 170 million dollars (on the grapevine), so I'm hoping they can afford a few orchestral sessions! They are planning to start shooting around April with three months of shooting followed by, at a guess, a couple of months of editing, so if it all works out OK I'll be called in towards the end of this year."

Matt adds: "The music Nathan wrote for the games lends itself to a full orchestral score, and we have ideas on how those pieces of music could be extended, but Core Design own the copyright on the original music, and though they've licensed the Tomb Raider concept to Paramount for the picture, I don't know if that includes the music. If not, we'll need to come up with something different, but in a similar style."

Added Spice

The keyboard rig in the Meode studio: from top, Roland D20, Ensoniq SQ1 Plus, Music Quest MIDI interface, Roland JV1080, Akai S3000 sampler, Roland JP8000.

The keyboard rig in the Meode studio: from top, Roland D20, Ensoniq SQ1 Plus, Music Quest MIDI interface, Roland JV1080, Akai S3000 sampler, Roland JP8000.

"When the Spice Girls job came along, that ended up being a mixture of orchestral and electronic styles. Peter Barnes, the show's lighting designer, wanted some music for the laser show and he wanted something with the feel of Carmina Burana. He'd heard the Tomb Raider music, so he got in touch with us and asked if we could combine a couple of tracks from Tomb Raider II. Obviously we couldn't use that music without permission, so I suggested we wrote something new and he agreed. We have a big orchestral start, then it changes into a pumping dance beat. The instruments and sounds we used gave it a Tomb Raider feel, and we were also given a script with timings where we had to incorporate a few Spice themes. Once he'd heard the four‑minute piece, he liked it and asked for sound effects to be added at certain points. Apparently there's going to be a DVD made of the show, but we don't know yet if our section will be on it. Hopefully it will, because of the visual impact of the laser show."

As Matt explains, the duo's work on Tomb Raider has opened a lot of other doors in the wider music world: "We've worked together since we were 16 or 17 and when we finished Tomb Raider III we thought it would be a good time to take off and do our own thing with the Tomb Raider name behind us. At least we thought that would keep people on the phone, which it did. Nathan adds: "We're targeting TV, film, computer games and the music industry."

The Studio

Nathan and Matt's current studio is quite compact, and is still based around Cubase VST running on a fast PC with an Event Gina soundcard. Most of the processing is done using Sound Forge, though I did spot an Alesis MidiVerb III on the shelf above a Focusrite Compounder and a Dbx Project 1 compressor. "The Compounder is great and the bottom end control really works well to pump up the bass, but the Dbx doesn't seem to do much at all," admits Nathan.

The keyboard setup comprises a Roland JV1080, JP8000, Ensoniq SQ1 Plus, a Roland D20 (which isn't used much now), and two Akai S3000 samplers with effects boards. Matt: "We'd like some more upmarket effects, but with Sound Forge and the Akai's onboard effects, we can do most of what we want. We can also add effects in Cubase using VST plug‑ins. We could do with some nicer outboard effects, but we don't do a lot of vocal work, and if we were to, we'd probably take it to another studio to mix. I don't add reverb until the final mix anyway, so that wouldn't be a problem.

"The mixer is a Mackie 8‑buss analogue desk — we can automate our MIDI and audio mixes in Cubase, and it's nice to be able to see all the faders at once, unlike a digital desk where you may only see 8 or 16 faders at a time. There are eight analogue outs from the computer so we can separate things out enough to get the job done. We've found the input stages distort really nicely when they're overdriven, and we've used that on some things. One track we wrote relies on a bass sound coming through the line amp and being heavily distorted, and we may occasionally do the same thing to drum sounds if they're too clinical.

"The meter bridge is rubbish, though it covers the cables — the meters are all post‑fader, which means they're irrelevant. You can't monitor the real line‑level input signals. Also, the VUs don't correlate with the main PPM meters at all. We had all the cable harnesses wired up professionally so there are no serious noise or hum problems. Whenever we add a new piece of equipment, we check very carefully to see how much noise it contributes.

"I enjoy mixing manually, which takes me back to the days before automation — then we were still flying things in off quarter‑inch tape. I run through the song until I get used to the take, set marks on the faders, then run through the mix and do the moves and the mutes.

"For monitoring we have a pair of Peavey monitors, which sound a little too flat for my liking, and a pair of Yamaha NS10Ms, which sound a lot better here than in our previous studio. The little Tandy Minimus 7s are also great for checking what your mix will sound like in the real world, though we've broken one of ours so now we have to check the mixes in mono! It's the next best thing to an Auratone. We also have a pair of Revox Studio IV monitors which are away being repaired at the moment. They're very old, but they're brilliant when they're working properly."

Nathan: "All the multitrack recording is done in Cubase VST, though we master to DAT. We don't have a hardware multitrack recorder. Now we have a fast computer, Cubase seems fine, though on the older computer, some timing problems came up if we'd recorded a lot of tracks.

"To avoid computer noise, we've improvised a home‑made voice booth outside the studio before now, and that's worked quite well. It was mainly carpets and egg boxes, and though egg boxes are no good at all for soundproofing, they seem to work well for making the recordings sound good. Here soundproofing is not a problem except when the planes fly over from RAF Brize Norton!

"Whenever we get spare time between projects, we work on our own stuff, which isn't always orchestral‑based. We do acoustic guitar tracks, dance music, ballads — we even do a little singing. The vocal mic is a Rode NT1 by the way, and it's incredible value.

"One interesting trick is to fix a dictaphone to the mic stand, put it in pause, then take a line out to another audio track. This really dirties things up, but it's also interesting to mix the clean mic sound with a little of the dictaphone signal, which gives everything that American squashed sound. Anything that has an input mic or output speaker gets tried out to see what it can do! The dictaphone has a very aggressive sound and it compresses everything. We also have a little BBC director's monitor which is a tiny cast‑metal box with a one‑valve power amp and an elliptical speaker. If we want to warm something up, we play it through that and then re‑mike it."

Creating Sound Effects

As well as putting together the music for their games, Nathan and Matt are also responsible for the large number of sound effects in each. The process of creating these allows them to exercise their experimental side: "A lot is actually done using pitch‑processed human voice," explains Matt. "For example, we had to do a few things to sound like Lara when the original voice‑over parts didn't quite work with the video. We redid a lot of things like screams, grunts, falls and that kind of thing."

"Quite a lot of the conventional sounds come from sound‑effects libraries," adds Nathan. "The Sound Ideas collection is very good, and they have endless ranks of Hollywood sound effects. It would cost too much to buy them all, but we buy in what we think we might need for a project. Even so, there are lots of areas for which there are no library sounds, so we have to create those ourselves."

"We smashed things on the kitchen floor to get the sound of a table being overturned in one scene," continues Matt, "and we recorded the sound of a chair being scraped across the floor for when somebody gets up quickly. We also use a lot of distortion to shape sounds — we've done explosions using our voices just processed with distortion and pitch‑shifting. Similarly we've done sounds for zombies and things.

"Post‑processing is nearly always done in Sound Forge. It's a brilliant package that lets you treat sounds in all kinds of ways, and it even has its own FM synthesis, so you can generate synthetic sounds. There are mountains of effects and everything is controllable. We use a lot of pitch‑shifting and amplitude modulation. It's amazing what you can do with pitch‑shifting — we took the sound of a bat squeaking and dropped it by around 36 semitones and it sounds almost like a train in the distance — very weird. We did a lot of that, taking sounds and then doing extreme things with them in Sound Forge to see what we could get out of them."