Kendrick Lamar

‘I’

Perhaps as a result of hip–hop’s heavy reliance on turntables and samplers, extreme pitch–shifts are common currency, but this double Grammy–winning production uses them more inventively than most. For instance, the chorus variation at 2:14 pitches “The world is a ghetto... sun gon’ shine” down about six semitones by my count, but the “I love myself” BV refrains are shifted more dynamically by three to five semitones to fit with the new bass line. The other great pitch stunt appears in the final verse, where at 2:47 the lead vocal slowly crossfades to and from a pitch–shifted version of itself, an effect made especially disconcerting because of the fleeting parallel–fourth sonorities heard during the crossfades themselves.

The mix is also stuffed with entertaining stereo movement.

There are a couple of prominent ping–pong delays, for example, the first on the main refrain’s “I love myself” (and made more audible in the mix by being slightly off–tempo — too slow for a 16th note, too fast for a 3/32–note) and the second a slower eighth–note six–tap ping–pong embellishing “night” at 2:38. The refrain’s “The world is a ghetto...” lyrics have something more subtle on them, I’d guess some kind of slow–rate modulation effect, because it seems to weave hazily around the panorama, its level in the stereo Sides signal pulsing roughly once per second. Outside the realm of effects, there’s also the call–and–response backing vocals at 1:58–2:14, which set up an alternating wide–narrow pattern, and some nice slow panning moves in the intro and outro: “This a world premiere” at 0:05; “I lost my head... world runs dry” at 3:02–3:16; and the higher of the two car sirens at 3:22. It seems a shame, though, that they didn’t give that last panning move a hint of simulated Doppler effect, seeing as they were so handy with the pitch–shifting elsewhere. Mike Senior

Rosanne Cash

‘A Feather’s Not A Bird’

This track features a gorgeous–sounding ensemble, using instrument timbres that all exude the rusty, weather–beaten maturity that Americana so often strives for, but with a truly hi–fi mix that combines musical sensitivity, warmth, clarity, width and air. The depth dimension is a lovely confection, initially pencilled in by the roomy snare and vocal slapback, before opening out luxuriously at 0:56 as the strings underscore the first title hook. Then the smooth, unfussy backing–vocal blends superlatively, slotting neatly between the band and the strings. It’s a characteristic that makes me think they were recorded as a group in stereo, rather than being built up via close–mic overdubs. Whereas the kick in many mixes more or less counterbalances the snare, here it’s surprisingly understated, sensibly focusing emphasis on the bass part’s melodic elements. The tambourine’s also noteworthy in that it feels more scraped than hit, supplying a sustain–heavy character which compliments the snare. My only slight tonal reservation is the gently overdriven vocal. Although this cuts through the mix well, its 3 to 4 kHz zone occasionally feels a touch strident in such a mellow context.

There’s some unusual phrase structure here as well. The song establishes the usual four–bar–unit norm through eight–bar intro and 16–bar verse, but then wrong–foots you by shortening the hook section by two beats with the band’s re–entry at 1:03. It’s one of those great moments where, as a listener, you don’t quite realise what’s happened for a few beats, and then you experience that kind of psychological ‘stepping up one too many stairs’ feeling as your expectations readjust to the new position of the downbeat. As you’re ready for the rhythmic trick to repeat with the second hook, this time the harmonic rug’s pulled from beneath your feet, as Ab is substituted for the previous iteration’s C minor. The next phrase contraction again catches you off–guard, though, with the final verse losing its last bar to an early entry of the final hook section, itself then settling into a traditional four–bar framework for the first time — which, for me at least, underlines the sense of musical closure. A production for the ears, the heart, and the mind. Mike Senior

There’s some unusual phrase structure here as well. The song establishes the usual four–bar–unit norm through eight–bar intro and 16–bar verse, but then wrong–foots you by shortening the hook section by two beats with the band’s re–entry at 1:03. It’s one of those great moments where, as a listener, you don’t quite realise what’s happened for a few beats, and then you experience that kind of psychological ‘stepping up one too many stairs’ feeling as your expectations readjust to the new position of the downbeat. As you’re ready for the rhythmic trick to repeat with the second hook, this time the harmonic rug’s pulled from beneath your feet, as Ab is substituted for the previous iteration’s C minor. The next phrase contraction again catches you off–guard, though, with the final verse losing its last bar to an early entry of the final hook section, itself then settling into a traditional four–bar framework for the first time — which, for me at least, underlines the sense of musical closure. A production for the ears, the heart, and the mind. Mike Senior

Rihanna, Kanye West & Paul McCartney

‘FourFiveSeconds’

There’s something very strange going on with the vocals here: it sounds like there’s some kind of electronically mangled backing–vocal part behind the lead line, but one that’s frequently out of sync with the lead’s melody and harmony. The question is whether it’s intentional, because Kanye West is a past master of taking what seem like unusably off–the–wall ideas and releasing them, effectively anointing them ‘the new cutting edge’ by force of personality. In this case, I think we’re actually hearing an attempt to deal with unwanted guide–vocal spill from Paul McCartney on the acoustic–guitar mic.

It’s not hard to imagine a scenario. Macca had a spare half hour, picked up a guitar and recorded a song demo for Kanye West, using separate close mics for guitar and vocals. West adapted the key and structure digitally to overdub new vocals with Rihanna. Excited with these additions, they wanted to rerecord the acoustic guitar without the spill, but McCartney couldn’t fit it into his diary soon enough, and they didn’t want to replace him with a sessioneer, lest the erstwhile Beatle’s name should drop off Rihanna’s cover art. They may also have tried (with limited success) removing Paul’s vocals with one of those whizzy spectral–restoration tools, which would provide an explanation for the vague, electronically smeared nature of these artifacts. I’d guess that some bright spark said “Hey, that actually sounds kinda cool” and suggested they fall back on that old production maxim: if it can’t be fixed, make it a feature!

It’s not hard to imagine a scenario. Macca had a spare half hour, picked up a guitar and recorded a song demo for Kanye West, using separate close mics for guitar and vocals. West adapted the key and structure digitally to overdub new vocals with Rihanna. Excited with these additions, they wanted to rerecord the acoustic guitar without the spill, but McCartney couldn’t fit it into his diary soon enough, and they didn’t want to replace him with a sessioneer, lest the erstwhile Beatle’s name should drop off Rihanna’s cover art. They may also have tried (with limited success) removing Paul’s vocals with one of those whizzy spectral–restoration tools, which would provide an explanation for the vague, electronically smeared nature of these artifacts. I’d guess that some bright spark said “Hey, that actually sounds kinda cool” and suggested they fall back on that old production maxim: if it can’t be fixed, make it a feature!

Of course this is all surmise, but there is one piece of evidence that suggests I’m not far off the mark: two roomy–sounding pitch–shifted vocal interjections in Kanye’s first verse (0:55 and 0:59), which sound like they’ve been allowed to escape any spectral processing as part of the ‘feature’. Pitch–shift those down five semitones and they sound a whole lot like Mr McCartney. Mike Senior

Chick Corea

‘Fingerprints’

The incredible musicianship of Corea’s Trilogy live album justly garnered itself a pair of gongs at February’s Grammy ceremony, but I find the sonics something of an acquired taste. Recorded on tour in various stops around the world, the 17 tracks inevitably vary slightly in this respect, given the different venues, but award–winner ‘Fingerprints’ provides a reasonably representative case study.

One fundamental question I find myself asking with most acoustic recordings is this: where am I, the listener, sitting? From a stereo perspective, we’re presented with something like a player’s perspective for each instrument here, such that the low notes of the piano join the hi–hat on the left–hand side, the bass and kick are both in the centre, and the piano’s high register reaches out towards the low tom. While there are plenty of precedents for this approach in the genre, I’ve always had a bit of difficulty getting my head round effectively listening from three different locations at once, and I’d much rather they’d taken their cue from the on–stage layout by presenting narrower piano and drums images located towards the left and right sides of the panorama respectively. That said, given the heavily out–of–phase piano pickup on some of the other cuts on this album (eg. ‘The Song Is You’), I’m not sure this would have been a viable mixdown option under the circumstances — the tonal implications of partially mono–summing the stereo mic pairs (to narrow them) would have likely been ruinous.

But this is only one facet of the ‘Where am I sitting?’ question, because there’s also the important issue of subjective distance. I find it disconcerting that the left and right extremes of the drum kit sound hyper–close, like they’re located right where my speaker cones are, whereas the snare and toms feel like they’re a good few feet back (despite decent definition), and the bass drum sounds indistinct and diffuse. All this is perfectly understandable in light of the live–oriented close–miking setup in the CD–booklet photographs (spaced stereo overheads pointing down from two feet above the cymbals, plus tight snare, tom and kick spot mics), but couldn’t a little more have been done at mixdown? Some transient reduction or HF softening of the overheads, perhaps, or an artificial early reflections patch to push the cymbals a little further away, and maybe some processing of the bass–drum close mic to bring that a little closer. You’ll find plenty of commercial jazz releases with similar depth–perspective distortion, but I’m no great fan of it, and I’d advise anyone starting out recording in this field against accepting this unquestioningly as the status quo.

But this is only one facet of the ‘Where am I sitting?’ question, because there’s also the important issue of subjective distance. I find it disconcerting that the left and right extremes of the drum kit sound hyper–close, like they’re located right where my speaker cones are, whereas the snare and toms feel like they’re a good few feet back (despite decent definition), and the bass drum sounds indistinct and diffuse. All this is perfectly understandable in light of the live–oriented close–miking setup in the CD–booklet photographs (spaced stereo overheads pointing down from two feet above the cymbals, plus tight snare, tom and kick spot mics), but couldn’t a little more have been done at mixdown? Some transient reduction or HF softening of the overheads, perhaps, or an artificial early reflections patch to push the cymbals a little further away, and maybe some processing of the bass–drum close mic to bring that a little closer. You’ll find plenty of commercial jazz releases with similar depth–perspective distortion, but I’m no great fan of it, and I’d advise anyone starting out recording in this field against accepting this unquestioningly as the status quo.

My final gripe is that the mix sounds like it’s too concerned with avoiding spill. I’m guessing, for instance, that the bass sounds rather unnatural (especially during the solo) because we’re mostly hearing its DI signal, not the mic. By the same token, I wish the hall mics had been used more throughout, because at the moment it sounds like they’re being ridden in only for the sections of applause — whereupon the band sound suddenly seems to cohere better to my ears. Mike Senior

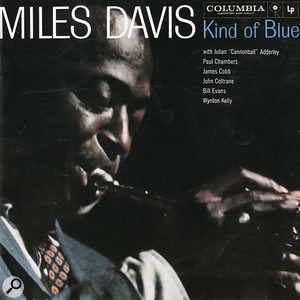

Classic MixMiles Davis ‘So What’

There are very few things you can say about this music that have not already been the subject of a PhD thesis, but it’s also quite interesting from the perspective of studio technique. The first thing to notice in the stereo mix is that the reverb is mono. This is great for Miles Davis, sitting as he is at the centre of the image, but a little disconcerting for John Coltrane’s and Cannonball Adderly’s solos coming from the left and right respectively. It also bugs me that Coltrane’s slightly rasping tone blends significantly less well than that of the other two soloists. It makes me want to reach over and angle the mic further away from the instrument’s bell.

An advantage of the mono reverb, though, is that you can listen to the mix’s stereo Sides signal to get an idea of the amount and character of room sound that was actually recorded (at least on the piano, drum and sax mics). And it’s pretty tight–sounding, to be honest — a hint of reverb tail, but none of the small–room character that most budget sessions have to contend with. This makes sense, of course, in light of surviving session pictures showing the musicians in a fairly close formation in Columbia’s capacious 30th Street Studio (a former church), the group partially walled in with tall gobos.

An advantage of the mono reverb, though, is that you can listen to the mix’s stereo Sides signal to get an idea of the amount and character of room sound that was actually recorded (at least on the piano, drum and sax mics). And it’s pretty tight–sounding, to be honest — a hint of reverb tail, but none of the small–room character that most budget sessions have to contend with. This makes sense, of course, in light of surviving session pictures showing the musicians in a fairly close formation in Columbia’s capacious 30th Street Studio (a former church), the group partially walled in with tall gobos.

On a totally different subject, I couldn’t help being tickled by this rubric from the original LP sleeve: “Scientifically designed to play with the highest quality of reproduction on the phonograph of your choice, new or old. If you are the owner of a new stereophonic system, this record will play with even more brilliant true–to–life fidelity. In short, you can purchase this record with no fear of its becoming obsolete in the future.” Or, to put it another way: “My name is Ozymandias, king of kings...” Mike Senior