Barnaby Smith (left) and Chris Bachman in the Sound Joint studio. The murals behind the duo aren't just there for visual effect — they also contain bass traps.

Barnaby Smith (left) and Chris Bachman in the Sound Joint studio. The murals behind the duo aren't just there for visual effect — they also contain bass traps.

Starting your own business is certainly not a commitment to be taken lightly — particularly if that business is a commercial studio — but musicians, producers and now studio owners Chris Bachman and Barnaby Smith don't do things by halves. The pair have recently made the leap from semi‑commercial production in a bedroom studio to become fully fledged professional studio owners, and to do this they've had to delve deep into the murky world of business plans, enterprise loans, business insurance and personnel management. The result of their labours is The Sound Joint studio in South London. The premises, comprising a 'chill‑out room', office and kitchen downstairs and a control room and live studio upstairs, are a triumph of DIY. The place is immaculately tidy, with all equipment contained within home‑made racks. The walls are tastefully decorated with artwork and, together with a scattering of comfy sofas, the place exudes an air of professionalism.

Barnaby: "You have to be quite businesslike to run a studio. Some musicians like a bit of an Aladdin's cave of gear, but if anyone's coming to do voiceovers, which is a reasonable source of income, they don't want to come into a pokey studio, and they don't like clutter. One musician we work for a lot is managing director of a publishing company. He just popped down one day, chatted to us and the relationship developed. We asked him why he uses the studio and he said it's because the place is really clean and we seem quite professional."

Setting Up Is Hard To Do

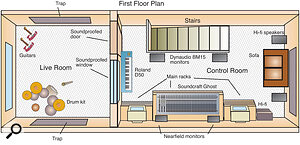

The control room, showing the main equipment racks and the Soundcraft Ghost desk.

The control room, showing the main equipment racks and the Soundcraft Ghost desk.

Prior to their current venture, Barnaby and Chris played as drummer and guitarist respectively in a band called Herb (who won the Sound On Sound Demo Doctor's 'top tape' back in March 1996), touring the university circuit and occasionally venturing into Europe. Barnaby: "We all lived in this upstairs flat in East Dulwich which used to be a little cinema, it was a bit like The Monkees. We'd spend three days rehearsing, two days doing part‑time work and then we gigged at weekends. We did OK but we didn't want to get stuck at a certain level. There's only so much you can do on your own, so Chris and I thought we'd be better off doing this."

Once the pair had made the descision to start a studio, they set about sourcing the funding to do the job properly. Their first port of call was the bank...

Chris: "It's hard to get money for a studio from banks because it's such a risk. They had a model for rehearsal studios but not for recording studios, so there was no reference. In the end, the options were the Prince's Trust and a London grant called Business 2000. You get the money and pay a very minimal interest, for example, we got £5000 from one source and payed back £5150 over three years. They give you an advisor who comes along each month and keeps you motivated, asking 'are you doing this?' or 'have you tried that?'

"We started doing talking manuals, so we based the business plan on that kind of work. People could see the money for that, but they start asking where the money's coming from if you say you're working with bands."

Barnaby concurs: "There are probably millions of people who want to be record producers, especially at the Prince's Trust, so we had to keep business‑minded, and with the talking manuals we had some actual figures to write down."

The now‑immaculate Sound Joint studio had previously been nothing more than an empty shell without soundproofing, decoration or any mod cons, so considerable building work had to be done, as Chris explains: "The upstairs was one big room with bare boards. The guy in here before had a software firm so there were wires running everywhere; it was a real mess. I did a maths degree, so the calculations for trapping in the roof and wall were not too tricky. We learnt from Paul White's books and a few other sources. The flooring we also did ourselves."

Barnaby's product design skills were put to good use in building all the studio's rack units from welded steel frames finished off with wooden panelling. "Barnaby got access to a workshop and built the racks, so we saved a lot of money that way," notes Chris. "My sister did all the artworks, which actually have traps in them. Little touches like that don't cost a lot but make for a relaxing atmosphere."

The duo took a cautious approach when building up their stock of studio equipment, fully aware of the potential to spend beyond their means. "The main thing was not to get into any debt to get here, and at the moment we have no debts," explains Chris.

Barnaby continues: "We knew a guy who got a whacking great grant and bought all the gear he would ever need in one go. He had a limited time to get his business turning over and it didn't achieve that so he had to give it all back. We wanted to get to this level as soon as possible, so we ploughed everything we made straight back in. We didn't want to get stuck in a position where we would have to make money to pay loans."

Working In The Sound Joint

Wherever possible, Chris and Barnaby prefer to use live instruments, such as their Yamaha drum kit, rather than sequencing.

Wherever possible, Chris and Barnaby prefer to use live instruments, such as their Yamaha drum kit, rather than sequencing.

The Sound Joint control room is centred around a Soundcraft Ghost 32‑channel desk, two TL Audio C1 valve compressor/preamps, two Tascam DA38 multitrack recorders, and a Soundscape SSHDR1 hard‑disk recording system providing 10 inputs and 12 outputs. A TDIF link allows the Soundscape and DA38s to be used as a single recording system. Chris explains the method. "We'll edit something in Soundscape and if we know that it's not going to change we'll slap it straight down and store it on the DA38s. Our desk isn't automated, so for mixing we tend to stick the faders at unity and then mess around with the levels in Soundscape — anything we put on the Tascams tends to be the stuff which isn't changing in volume throughout the song. We've also got some Soundscape plug‑ins like Audio Toolbox, time‑stretch, delays, compression, flanging and there's a very good 4‑band mastering compressor inside as well.

"The best things we've bought recently are the two TL Audio stereo preamps. We chose them for the compressor, not the mic preamps, but now we don't really compress to tape. We go straight through those to the Soundscape. We've got four inputs from those which are used for the bass, snare drum and the two overheads. We only put a couple of extra mics on the kit which go straight through the desk, and everything from there on, like guitar and bass, goes one at a time through the TL Audios."

Barnaby is also enthusiastic about the preamps' performance. "Before we got the TL units we couldn't get the drum sound we wanted. The snare never sounded punchy. It was like being slightly myopic and then going to the optician, but I think you have to go through the process to appreciate and realise what you've got. In the live room we used to have DI boxes, but the preamps have a keyboard and guitar line input. We've got pair of SM58s, pair of AT4033, a D112 kick drum mic and AKG 3700 for the snare. We'd still like to get a nice valve mic."

Chris: "It's good to do what we've done and work up from a small‑grade studio with low‑grade gear because you work hard to get every ounce of quality from what you have. We've always monitored on little hi‑fi speakers, the main reason being that that is what people have in their houses. Now we've got three sets of speakers which are all quite different; if it sounds good on more than one pair then you're pretty much there."

Having decided to fortify the studio without getting into any long‑term debt situation, Chris and Barnaby have spent their money specifically on recording equipment and consequently don't own any sound modules. Wherever possible, they prefer to have real instruments such as drums and guitars played live, rather than using the sequenced equivalents. "Initially we thought of getting a load of samples for a library, but it's easier to just play things," explains Barnaby. "Even when you're trying to put a guitar part to an existing drum part, there are so many little things you're naturally doing to make it fit. It saves you having to go through all the samples to find the right one and there's still a lot of editing and trimming to do even when you find it."

"We try to use live instruments as much as possible," continues Chris. "One guy recently came in with his synth and we replaced every single sound with live stuff. It had a sequenced feel to it still but it was all live. We can create a sampled loop or feel with the editing in Soundscape. Barnaby will go in and play 16 bars then we'll take the best bits and chop them up to get a very tight feel. Effectively we're creating our own samples."

Barnaby: "You don't hear timing errors these days. In stuff done 20 years ago, it was all over the shop and that was an acceptable part of the character, but it sounds wrong now because everything's bang‑on."

The duo's Akai sampler is used mainly for the sound of instruments that it would be impractical to record: "We tend to layer sounds on the sampler and use it as playback for the things we haven't got," explains Chris. "We don't have a grand piano, so we use East West's Ultimate Piano CD, for example."

Method Not Madness

Chris and Barnaby's ultimate ambition is to become established producers, selecting the artists with whom they wish to work. Chris explains: "Production work is what we're interested in, rather than selling the studio day‑by‑day, because that can be quite dull in some senses. We want to be a bit picky and choosy and work with bands with whom we have a big input," insists Barnaby.

Chris: "Quite a few acts we've worked with have just been singers with a management company or small label, so they come in with a song, or just half a song. We've got a couple of local musicians we can call on, one is a keyboard player and the other plays bass. Barnaby plays drums and I play guitar and we can program stuff so we can be flexible. Sometimes we'll be playing everything, sometimes nothing, depending on the budget. We try and do as much as we can ourselves."

Barnaby: "We tell people we want to make them as commercial as possible and a lot of time they think 'Oh my God, commercial, that means Whitney Houston or Phil Collins,' but it means take what they've got and make that as commercial as possible. We don't try to second‑guess what the record companies want. People ask 'How is this going to make me sound?' but we don't know until we've done it — it will be good, but music evolves. You can't have too much of a fixed idea. If they're a great band you work out which elements are great and get those elements in. A lot of the time it's brevity: a nine‑minute song may have three minutes of good material in it so we'll condense it. You've got to catch people's attention; there will be plenty of time later to stick a nine‑minute song somewhere on an album. Sometimes it's the producer's job just to say 'It's all good' although the client may put their hands on their hips and say 'So what have you actually done to produce this track?'

"It's important to be quite confident, because a lot of the time producing is about making people feel comfortable, and if they're happy when they record, they will generally go home happy. People who are not experienced will come in and go, 'That's out of tune', or 'This isn't good enough'. But you get to the point where you have to say 'I know this is fine, don't worry about it."

"I don't think we would ever work for free now, even if we were absolutely loaded," admits Chris. "It makes people blasé," explains Barnaby. "We had a situation where we recorded a band for free over four or five days because we liked their stuff, and then on the fourth day they said they were splitting up anyway! I said 'Why didn't you just tell us' and they said 'Because it was free, we might as well do it!' If they're not prepared to stump up just a little bit they're not serious. You find out who the time‑wasters are quite quickly!"

Working as professionals with a hard‑earned reputation to maintain, the pair have to manage studio time with care to ensure the best results. Chris: "When we work for bands on the lower level who haven't got backing, you can't spend ages doing stuff so we try to do two tracks in four days. That's a tight time schedule to get something that's release‑quality, so we actually give people a timetable. We say we'll do the drums between these times and if we get to the point where they're at a certain level, but we'd like it to be better but we've gone past that time, then that's it. Otherwise the vocals, which go on at the end, are rushed — which is mad because they're the most important thing. You've got to prioritise and have an organised mind."

Talent Scouting

In a drive to find exciting bands to produce, Chris and Barnaby organised several demo competitions. The judging process proved to be a learning experience...

"It's hard to find bands that are good." Chris admits. "We got hundreds of tapes and started of listening really carefully to three, four or five tracks of each. In the end we were just listening to the first few seconds of the first track, partly because we had so many but mainly because you can tell straight away if it's any good. I used to think 'How can record labels do that? That's awful!' but we rapidly got to that stage."

"Now we know how A&R people are going to be thinking so we're never going to do that. We eliminate any noodling intros," explains Barnaby. Chris continues. "A lot of time the recordings were pretty good technically, but if I'd written some of those lyrics I'd burn them immediately! We go for the obvious things. If the vocals are good, if it's catchy. You get about two from every hundred tapes that have both of those things, if you're lucky!"

Barnaby: "People are prepared to pay £600 to draw up a contract and the same amount again for photos, but if they can get a recording done for free they'll try and do that, and I'll be saying 'Surely that's the most important bit?' One band spent £14,000 on packaging and promotion, but when we said we were interested in doing something and gave them a really cheap price, they we saying 'This sounds a bit expensive!' At the end of the day it's what's on the tape that's most important. One of the winners was just a cassette with the name of the band and phone number scrawled on it."

Tip From The Top

Barnaby: "We used to live opposite a guy called Mike Milliner, who was one of The Pasadenas. There were five of them and they did a lot of harmonies, but Mike said they often used to have trouble tuning the backing vocals. Listening to each one individually they'd sound in tune, but put them all together and they wouldn't sound right. Then a producer told everybody to swap around. They'd all sing five lines, then swap their lines and double up, and that seemed to eradicate the tuning problems. So we do that quite a lot."

Gear List

- Soundscape SSHDR1 computer recording system.

- Soundcraft Ghost 32‑channel desk.

- Dynaudio BM15 active monitors.

- Akai S3000XL sampler.

- TL Audio C1 valve compressor/preamp (x2).

- Tascam DA38 digital multitrack (x2).

- Tacam MMC38 sync/machine control.

- Tascam DA20 & Aiwa XD‑S260 DAT machines.

- Tascam CDRW700 CD writer.

- Kenwood KA 3020SE amplifier.

- Monitor Audio speakers.

- JPW stereo speakers.

- Behringer Composer compressors.

- Behringer Intelligates.

- Lexicon MPX1 multi‑effects.

- Yamaha REV500 reverb.

- Alesis Quadraverb multi‑effects.

- Digitech Legend multi‑effects.

- Behringer Ultrafex enhancer and surround processor.

- Alesis 3060 compressor.

- Alesis MEQ230 EQ.

- Audio Technica AT4033 mic (x2).

- TOA K4 condenser mic.

- AKG D112, 118 and 1200E mics.

- Shure SM58 mics.

- Pentium PC running Cubase.

- Alesis D4 drum module.

- Yamaha 9000 drum kit with Sabian andZildjian cymbals.

- Mesa Boogie Mk4 amp.

- Signex patchbays.