More and more musicians are trying to escape the sterile confines of modern commercial studios in favour of their own creative environments. Brendan Perry's highly individual recording space is uniquely suited to his eclectic style, as John Walden reports.

If you died and were allowed to enter recording studio heaven, what would it be like? Well, let's see... suppose we take a range of high‑quality recording equipment, some fabulous and exotic musical instruments, a beautiful building in a quiet rural location and then add, for good measure, friendly company over a cold Guinness just a couple of minutes up the road. If that sounds like heaven to you, you'll understand the appeal of Brendan Perry's Quivvy Studio.

The Ends Of The Earth

Brendan's work as one of the founder members of the band Dead Can Dance will be familiar to many SOS readers. Their eclectic mixture of musical styles, spanning some nine official albums, gained them a huge world‑wide following but has defied classification ('world beat'?). Brendan's somewhat diverse musical output is, in part, a reflection of first‑hand experience of some varied cultural influences. Although raised in London during the 1960s, his route to his current base in Ireland was not a direct one. In the early 1970s, just as his interest in the guitar was developing, his Anglo‑Irish parents decided to emigrate to New Zealand. While attending a church school in Auckland, Brendan spent a lot of time playing guitar with his Maori and Polynesian classmates.

In his late teens, within a few days of a chance meeting with a punk band called the Scavengers who happened to be looking for a bass player, Brendan found himself miming with the band on New Zealand's version of Top Of The Pops. Without ever having played a single note on a bass, Brendan was placed in the rather strange position of being a minor musical celebrity! By 1978, the New Zealand punk scene was becoming less attractive and the band relocated to Australia, signing a management deal under the new name of The Marching Girls (the New York Dolls' original name) with ex‑Split Enz guitarist Wally Wilkinson and producer Dave Russell. However, the music became more pop‑based, and by 1980 Brendan decided it was time to move on.

It was at this time that Brendan's interest in music technology began to develop. "I began to teach myself percussion, and started to experiment with synthesis, tape loops, electric guitar and bass," he recalls. "Listening to post‑punk bands such as Public Image and Joy Division inspired me to create music where sound was used to express tangible emotions and atmospheres. I wanted to paint soundscapes."

During this period, Melbourne had a very interesting music scene centred around what was known as The Little Bands movement. Brendan explains: "These groups were made up largely of people who had no background or formal training in music but who were prepared to play instruments in an experimental and somewhat unconventional fashion." Brendan's involvement in this movement led to a meeting that was significant in shaping his subsequent musical direction. "It was at one of these sessions that I met Lisa Gerrard, who was performing with a band called Junk Logic. At the time I thought her music was too avant garde even for my somewhat broad musical taste. I particularly remember one song about finding a man in the park and wanting to bring him home to keep in her wardrobe, which she sang while ceremonially attacking a Chinese dulcimer with two bamboo sticks!"

With some idea of the type of musical future he wanted to create now in place, in 1981, Brendan formed Dead Can Dance with Simon Monroe (drums) and Paul Erikson (bass). Within a few months Lisa Gerrard joined the line up to provide electronic percussion and backing vocals. By 1982, it was clear to the band that their musical direction was not going to find support in the relatively modest Australian music scene and they relocated to London. On arrival, they sent a four‑track demo to several independent companies in the belief that they would retain more artistic freedom if signed to an independent.

Ivo Watts‑Russell of 4AD was impressed enough to offer Dead Can Dance a one‑album deal, and in June 1983 the band went into Blackwing Studios (also based in a converted church) to record their first, eponymous album. For the band, and the collaboration between Brendan Perry and Lisa Gerrard in particular, it was to mark the start of some 15 years of recording success. However, in 1998, after the release of the 1996 Spiritchaser album, Brendan and Lisa Gerrard finally decided that Dead Can Dance had run its course. Both wanted to move to other projects, including film work (Lisa Gerrard recently won a Golden Globe with Hans Zimmer for the score to Ridley Scott's Gladiator), and having a high‑quality studio facility of his own has been a key element in making Brendan's diverse projects possible.

Take One Church...

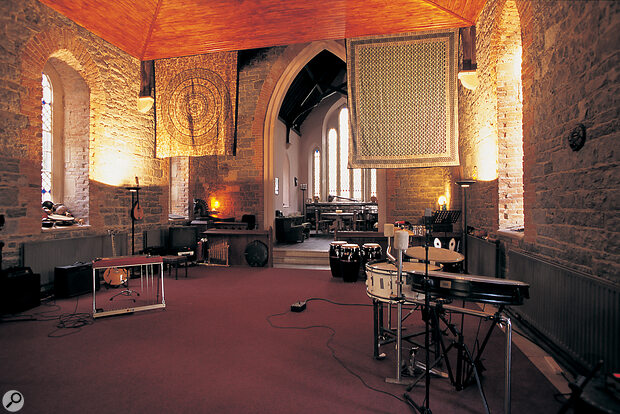

Claustrophobia is not a danger at Quivvy Studio. This shot was taken from the space where the altar once stood, looking towards the raised control room. Most of Brendan Perry's extensive collection of percussion instruments is visible.

Claustrophobia is not a danger at Quivvy Studio. This shot was taken from the space where the altar once stood, looking towards the raised control room. Most of Brendan Perry's extensive collection of percussion instruments is visible.

Quivvy Studio is installed in a renovated church, originally built in 1855, which Brendan purchased in 1993. "The church was put on the market because of a dwindling Protestant congregation," he explains. "It is situated in an oxbow just south of the river Erne, which forms part of the present‑day border with Northern Ireland. I used to get regular daily visits from British Army Chinook helicopters patrolling the border." Fortunately, with the border between north and south now a more relaxed environment, only the occasional tractor disturbs the peace inside the studio.

Brendan's reasons for developing Quivvy were a combination of the creative and financial: "I was horrified by the amount of money that record companies paid out to studios to record their artists — who, in turn, would see no profits until they had at least paid back the recording debt through record sales. The solution for me was to take the money that would have been paid to a studio and invest it in my own studio. This in turn would give me more creative control and ensure that I would see the profits from record sales sooner."

Unsurprisingly, however, the building needed considerable work before it could be turned into a functional recording space. "The church was in good condition structurally, but had no amenities," says Brendan. "To provide a water supply, a spring had to be bored about 150 feet through the limestone rock before plumbing could be installed. I had 80 percent of the plaster removed from the cut stone walls to improve the general acoustics. With my parents' help, we constructed a gallery at the opposite end from the altar to form a control room. I have always liked the layout of old radio‑style studios, where the control room looks down onto the recording area, affording greater visibility and acoustic isolation."

A problem that most studio designers don't have to face was a resident colony of long‑eared bats, who would regularly spend the night covering the church contents with droppings. "I was loth to get rid of them on ecological grounds, as they are a protected species," says Brendan. "I came back one night from the pub with a few friends, worse the wear for drink, and we played Led Zeppelin at full tilt into the wee hours. The next morning I awoke to discover the problem solved. The majority of the bats had fled, and about 15 or so lay lifeless at the base of the walls — which I can only deduce they must of flown headlong into, their ability to navigate by way of sonic imaging being confused by Bonham and company's wall of sound!"

The biggest problems concerned humidity, dust and maintaining an even temperature for the equipment. The heating of this building alone is an epic undertaking, requiring no less than 14 double concentric radiators, each 10 feet long, and an industrial boiler large enough to heat a small factory. Many of these problems could have been resolved by subdividing the space into more manageable sizes, but Brendan decided that this would destroy the ambience and acoustics — the very things that made it such a special environment to work in. "The acoustics at Quivvy would certainly not suit someone who prefers to work in an anechoic setting. It is a very live space that has its own set of limitations as well as advantages. The obvious limitation is lack of separation between instruments that have a lot of high‑frequency dynamic energy, such as a typical rock band might produce. For acoustic solo recordings and vocals it is exceptional, though, providing several natural room settings in different parts of the church."

With fabulous natural light through the stained glass windows in the live recording space, the inside of the studio has a wonderful atmosphere — a more 'stress‑free' recording location is hard to imagine.

Pews Out, Processors In

Brendan's Quivvy Studio is housed within a disused church, originally built in 1855.

Brendan's Quivvy Studio is housed within a disused church, originally built in 1855.

The studio houses an impressive range of both recording equipment (see the Some Quivvy Kit box for full details) and musical instruments, the latter illustrating Brendan's fascination with all things percussive (see the Perry's Percussion box). On the recording front, there is a mixture of both digital and analogue equipment. While making use of current digital recording media, Brendan is a big fan of analogue tape. "I currently record onto a Studer 822A two‑inch 24‑track, after experimenting over the years with a range of formats. To my ears at least, the Studer just seems to be the most faithful recorder of the source sound of any recording format that I know. Of course this comes at a premium, and because I don't like to use noise reduction I have to run the Studer at full speed with Quantegy Special Formula 499 tape, which only gives me 16 minutes of recording time per tape."

To help keep tape costs and wear and tear on the Studer down, Brendan uses an alternative recording strategy when developing new material: "If I'm working on demos for new material, I tend to use Logic Audio Platinum running on a G3 Mac that is fitted with an Emagic Audiowerk8 soundcard and sync'ed to a Tascam DA88 recorder. Generally speaking, I strive to strike a healthy balance between the digital and analogue domains."

Brendan tries to keep the recording chain as simple as possible. "I always endeavour to retain acoustic recordings in an analogue chain — mic to desk to tape recorder — and then apply a combination of digital and analogue processing if required. I rarely, if ever, commit electronic instruments to tape. I prefer to record the final mix with the multitrack and sequencer locked together in sync." As Brendan is also involved in composing for film, facilities for synchronisation of the multitrack to video are also in place.

The Creative Process

A Mackie 32:8 with 24‑channel add‑on dominates the Quivvy control room.

A Mackie 32:8 with 24‑channel add‑on dominates the Quivvy control room.

Brendan's material is usually derived in the first instance from improvisations on various instruments, ranging from stringed (guitars, oud, bouzouki, tampura, hurdy‑gurdy) to percussion (congas, djembe, dumbek, drum kit, bodhran) to keys (samplers and synthesizers). "Apart from film scores, where you normally have to work with prescribed images, I usually take my inspiration from the sounds I derive from these musical instruments. Often songs will then develop from vocalising sounds along with the music until a kind of musical tapestry begins to develop."

Brendan employs a number of distinct methods when writing. A basic guitar and voice combination is one example: "The guitar usually sets in motion a musical progression which informs and guides the voice and more often than not they reverse roles in mid‑flight, the voice acting as a guide for the guitar as the inspiration takes hold. Generally speaking this is a very orthodox approach to songwriting but one which rarely fails to produce a rich vein of material for me. I would then commit a live performance of the song to tape and then, having synchronised this recording to a sequencer via a SMPTE track, begin to lay down the accompanying instruments such as bass guitar, strings, and synths on MIDI tracks, in order to piece together an arrangement."

Given the importance of percussion at Quivvy, however, it is not surprising this also plays a key role in the creative process. "I'll often put rhythms down either by overdubbing live percussion takes in order to build an entire rhythm section or using sampled sounds with a sequencer. More often than not I would use a combination of both MIDI and live recordings to achieve the end result. When I am happy with the basic groove I usually move on to incorporate bass parts. These help to act as a bridging agent between the rhythm and future melody‑ and harmony‑orientated parts."

For many musicians who spend much of their time working alone, sequencing plays an important part in developing musical ideas, and Brendan is no exception. On this front, a recent change in the studio has taken place. Having been a dyed‑in‑the‑wool Steinberg user ever since the days of Pro 16 for the Commodore 64, he has recently changed over to Emagic's Logic Audio Platinum, running with a G3 Macintosh, and uses this in combination with various samplers: "The change to Logic was out of desperation after I could not get Cubase to function with a Korg 1212 soundcard on my blue and white G3. Neither Steinberg nor Korg seemed able to resolve the problem. A supplier then suggested I try the Logic/Audiowerk combination instead. I was not looking forward to the massive learning curve that everyone talks about with Logic, but to my surprise the transition was effortless and I was up and flying in a matter of days. The Logic interface is so flexible and I love the way it can be shaped to my own way of working. To me, Cubase now seems unwieldly by comparison."

Fully Booked

Quivvy is central to several projects Brendan is currently developing. One is the production of a short film titled Mushin with Graham Woods from Tomato. "The film is based on the Zen practice of achieving 'no mind' (Mushin). We hope to enter the film at various film festivals before licensing it to various arts‑orientated television networks," he explains. Brendan is also preparing ideas for the score to Eugene Brady's (The Nephew) next feature film, which has the working title Aoiffe.

Last autumn Brendan, assisted by his brother Robert, ran workshops on Afro‑Cuban (Rumba) and West African (Manding) traditional hand percussion at Quivvy. Thanks to advertising on the world wide web, all 24 places were filled within a few weeks, with people coming from as far afield as Poland, Turkey, Austria and Los Angeles. Brendan holds free classes for those living locally and has a further series of workshops for advanced‑level percussion players planned for summer 2001.

A new solo album is also in development and all recording is being undertaken at Quivvy, and in a change from much of his recent work, the new album involves a number of other musicians, including Arnie McGoven (who also assisted with some of the work done in the church conversion) on drums. If the album is anything like as inspiring as the studio it was recorded in, it will be well worth the wait!

Some Quivvy Kit

RECORDING EQUIPMENT

- Studer A827 two‑inch 24‑track.

- Mackie 32:8 mixing console. "This has a 24‑channel add‑on for my keyboards and samplers, and Ultramix automation."

- Emagic Logic Audio Platinum running on a G3 Mac with Audiowerk8 soundcard.

- Dynaudio MP3 monitors.

- 2 Electrovoice Q44 power amplifiers.

- Tascam DA88 digital multitrack.

- Yamaha O1V digital mixing console.

- Mark Of The Unicorn MTP AV MIDI interface

MICROPHONES

- Neumann U87s.

- B&K 4006s.

- AKG 414Cs.

- AKG C12 valve mic.

PROCESSORS

- Lexicon 200 Digital Reverberator. "I bought this off an American PA company after using it for my onstage vocal mix. I love the warm natural reverbs and the hands‑on big knobs and sliders which give you instant results. I wish more companies would incorporate hands‑on interfaces for their digital products. I am sick to death of reading through menus on small screens and going blind in the process. Musicians like to play with their knobs while technicians prefer to twiddle with theirs it would seem!"

- Lexicon PCM70 reverb.

- TC 2290 delay.

- Sony R7 reverb.

- Focusrite stereo valve mic preamp.

- Drawmer 1960 valve compressor.

- SPL Vitalizer enhancer.

- BBE Sonic Maximizer 822A enhancer.

- Roland RE201 Space Echo.

- TC G‑Force guitar effects.

KEYBOARDS, SAMPLERS, & ELECTRONIC INSTRUMENTS

- Akai S3000 & S5000 samplers.

- Big Briar Theremin.

- Boomerang phrase sampler.

- Emu Proteus 2, Proteus 3 and Vituoso 2000 modules.

- Korg Triton Pro X (used as the master keyboard), Prophecy, O1/RW and M1.

- Novation Supernova IIR module.

- Roland MC505 groovebox, R8 drum machine, Octopad and HPD15 Handsonic electronic percussion unit. "Percussion is a big part of my music. I rushed out to buy this little unit [HPD15] after reading the glowing review in Sound On Sound [see our October 2000 issue] and am really pleased with it."

- Woodstock harmonium.

WIND INSTRUMENTS

- Gemshorn.

- Bombarde (a Breton instrument).

- Ocarina.

- Chinese shawm.

- Ney flute.

- Arghul (Egyptian shepherd's pipe).

- Irish low D whistle.

- Snake charmers (Indian).

- Brazilian bird whistles.

- Duduk (Armenian).

- Mey (Turkish).

- Maui Xaphoon (Hawaiian).

Perry's Percussion

Brendan has a very extensive collection of percussion instruments from many traditions, largely acquired on his travels as a tourist or a performer and, more recently, via the Internet. One thing that clearly matters to Brendan is drum tuning: "Even with the best equipment and all the willpower in the world, you cannot make great‑sounding recordings with a badly tuned drum. It amazes me the amount of drummers who are completely lost when it comes to tuning. Instead of addressing the problem of a ring in the skin by tuning it out, they or the engineer will simply reach for the damper switch, moon glue or gaffer tape. This also suppresses all the other harmonics in the process and you end up with something that resembles a cardboard box. Tuning drums is a straightforward task, and with practice and a common‑sense approach you can train the ears to hear the subtleties involved."

One of Brendan's percussion workshop students from Berlin recently presented him with a David Roman frame drum that has a unique method for keeping its natural skin in tune. It has a rubber inner tube located between the skin and the wooden frame, into which air is pumped to raise the pitch uniformly across the drum head. "This represents a major revolution in skin tuning as natural skins are very susceptible to atmospheric conditions such as humidity and temperature."

(If you want to find our more, David Roman has a web site at www.DavidRomanDrums.com, and Brendan recommends www.drums.org/djembefaq/section1... as a source of further information on drum tuning.)

Brendan's collection includes:

- Timpani.

- Udu.

- Quicas.

- Djembes.

- Dununs.

- Talking drums.

- Timbales.

- Congas.

- Bongos.

- Darbukas.

- Frame drums (tar, bodhran, bendir, daf).

- Tonbak.

- Rainstick.

- Shekeres.

- Cabasas.

- Surdo.

- Tablas.

- Agogos.

- Pandeiro.

- Kokorikos.

- Dumbek.

- Devil's wand.

- Bullroarer.

- Caixixi.

- Berimbau.

- Gongs.

- Angklung (Indonesian).

- Bamboo jaw harp.

Percussion Approaches

Given his obvious interest in all things rhythmic, it is hardly surprising that Brendan has developed extensive experience in recording live percussion, and has a good deal of advice to offer on the matter: "As in most microphone recording scenarios, you need to decide which aspects of the sound you wish to capture before choosing the type of microphone and its eventual position. Use your ears to determine where the 'sweet' spot is located, then ensure that the microphone you situate there is suitable for the specific job in hand — dynamically and tonally. The greater the distance from the drum, the greater the need for a microphone with a larger dynamic range. For most bass drums I would use the AKG C12 valve mic. A bass drum's energy tends to displace a lot of air, so I would use a mic that captures a good portion of this energy."

When recording in stereo, Brendan opts for a 'less is more' approach. "A cardioid stereo pair placed either side of a drummer's head will give you more or less the same dynamic levels and tone that the drummer hears during his or her performance, though you need to ensure that the pair are in phase. This would also be true if applied to a conguero performing on congas, or a timbale player. Personally, I think a very common mistake that stems from the PA‑system approach is to close‑mic every drum. This means that the various microphone response levels and the engineer's disposition towards the music affects the percussion player's dynamic balance between each drum, and therefore alters the performance."

Brendan also favours the tonal response that is obtained by avoiding very close mic placement: "No matter what microphone you use, you will never achieve true bass response from larger‑skinned drums when close‑miking. A useful phrase to remember is 'bass needs space'."

When it comes to rescuing lifeless sounding drums that have already been committed to tape, Brendan favours a lo‑tech solution. "I generally feed the equalised signal of the offending track to a large speaker cabinet placed in a live‑sounding room, then rerecord with a condenser mic to a spare track. This seems to reintroduce some harmonic energy and ambience missing from the original recording, without affecting the drummer's previous performance. I don't think you can simulate this method with digital processors or plug‑ins. I am sure there are psychoacoustic explanations for the difference between real and virtual settings, but all I know is that the end result speaks for itself."