We conclude our in-depth guide to the world of library music with an essential cut-out-and-keep explanation of the key words and phrases you’ll hear.

Over the last 10 months we’ve explored the world of library music. Also known as production music, it’s a rewarding little niche of the music industry — or, more accurately, of the film, television and advertising industries. Having had 13 years’ experience as a writer then publisher of library music, it’s been my pleasure to parcel up what I’ve learned and help you to understand how it works in case you’re embarking on this path yourself. I highly recommend that you consider it!

Most of this final instalment in the series will be a handy Dictionary Of Library Music, condensing many of the points discussed over the previous nine articles into an alphabetical list. If you don’t have all of those articles, look them up on the SOS web site and consider buying the PDFs to read deeper and get the best out of this series (see the links in the ‘Further Reading’ box). A good read of this little dictionary should help you remember some of the most important points, and will also make a useful reference if you find yourself baffled by library music jargon where, reflecting the influence of publishing, film and TV terminology, composers are ‘writers’, sub-publishers are ‘agents’ and tracks are ‘cues’.

A Dictionary Of Library Music

Being paid up front to generate library music is, alas, now rare, so the chances are that any recording costs will have to come out of your own pocket.Advances

Being paid up front to generate library music is, alas, now rare, so the chances are that any recording costs will have to come out of your own pocket.Advances

Less common than they were, an advance is an initial payment to the writer from the publisher which is later offset (‘recouped’) against your share of royalty earnings. It’s a bit like a loan, but you never have to pay it back if you don’t earn any royalties! (See article 2 in this series.)

Advantages of Library Music

Compared to other income sources from music, library music can give you more artistic freedom, as well as better and more stable income if you write a lot of great music for great companies.

Agent

In library music, an ‘agent’ is another word for a sub-publisher: a company that represents your main publisher in another territory. Sub-publishers in some high-earning territories like the USA and Australia can earn you better royalties than the publisher who hires you. In terms of earnings, the agent takes 50 percent of mech/sync fees, then passes the other 50 percent to your publisher, who then gives the writer whatever is stated in the Writer Agreement. (See article 2.)

All Media

In synchronisation licences, ‘All Media’ is the highest price tier, and indicates that the client has paid for the right to distribute the video containing the music in all formats including cinema (theatrical) trailers, TV, radio and online.

Alternative Versions

In library albums you are often expected to hand over ‘alt versions’, such as drums only, no vocals, strings only and so on. These can be very handy for a client in a rush.

Approaching Library Publishers

See articles 1 and 9. It is recommended that your first email to a publisher is addressed to a specific person, and shows that you understand something about the company and what they do. Ideally, send a link to 12 finished tracks which sound amazing, have great titles, are available to publish, form a good album concept with a good title that would fit in their catalogue and fills a gap that they don’t have. Anyone who follows this advice will get their music placed with good companies.

Assignment

There are two different classes of contract for intellectual property: a licence, where you retain ownership but grant certain rights, and an assignment, where you hand over ownership either in perpetuity or with a reversion clause. Typically, writers assign ownership to the library music publisher, and the publisher grants licences to clients.

Audio Format

As library music is mainly used in the film and TV industry, it is delivered as 48kHz, 24-bit WAV or AIFF files. Final mixes are expected to be unmastered, with no bus compression or bus EQ.

Producers have been known to go to great lengths in pursuit of authenticity.Authenticity

Producers have been known to go to great lengths in pursuit of authenticity.Authenticity

See article 4. Clients often talk about craving authenticity, and the lack of it in some library music is often a pet hate. Authenticity can mean using as many expertly performed live instruments as possible, and working within a style that you understand well. The opposite of this is creating dodgy imitations of styles you don’t understand, played on tinny samples.

Blanket Licence

A blanket licence or blanket deal is where your publisher and their agents offer an annual subscription to a client to use anything they want from the library. Different publishers have different systems for distributing blanket incomes to writers, so it can be worth asking what method they use.

Broadcast Territory

In a licensing deal between your publisher and a client, this clause specifies where in the world the video using your music may be broadcast. It is usually ‘The World’, or even ‘The Universe’, for publishers worried about satellites or the Internet not really being in The World.

Business Models

See article 2. There are a number of different business models employed by library publishers. Some sell to the general public online, some offer buy-outs (money up front, no money later); non-exclusive libraries will all take the same material, but might earn you less than an exclusive library, while traditional UK libraries will offer you a share of sync fees (often 50 percent).

Buy-out

See article 2. A ‘buy-out’ is where a library publisher offers money up front to ‘buy you out’ but gives no share of sync royalties later.

CAE/IPI Number

An IPI number (formerly known as and still often referred to as a ‘CAE’ number) stands for Interested Party Information. In the world of music publishing, every interested party in royalties, including publishers and composers, has a unique IPI number provided by their Performing Rights Organisation, helping to make sure that royalties go to the correct company or person.

Catalogue Acquisition

Large publishers often buy up smaller publishers, attracted by the enduring royalty-earning value of their library music catalogues. When this happens to your publisher, you could lose your main point of contact (if they don’t join the buyer as an employee), and your music could become buried among their millions of tracks. Alternatively, your music could get a new lease of life, if they bring newer and bigger clients. Either way, an acquisition can change your fortunes if all your work is for one company.

Clearance

One of the worst nightmares for any brand, film studio, trailer house, TV producer or network is to broadcast music that wasn’t legally cleared (either because they have no licence, or the licence doesn’t grant the permission they needed) which then becomes subject to take-down notices or penalty fees. Therefore, production company staff in music decision roles need to be knowledgeable about ‘clearance’: what permission is needed from whom, and how a licence agreement should be worded to enable the usage they require. Major film studios employ independent clearance specialists who do nothing but send out carefully worded quote requests and licences all day.

Clients

See article 4. Clients of library music are video and radio production companies including TV broadcasters (networks), independent producers of dramas and documentaries, film-makers, promo makers and advertising agencies.

Commercial Music

See article 4. In the library world, ‘commercial music’ refers to music released by artists for sale or streaming to the public within the mainstream record industry. Using commercial music in film and TV production is often an attractive option for clients, and it is therefore one of the main sources of competition for library music (alongside custom music).

Composer

Confusingly, composers are always called ‘writers’ in the library music world.

Consent Form

If you have a performer on your library music track, make sure you tell your library publisher and send them a signed consent form, where the performer hands over the copyright in their performance in return for a fee. Without this, you and your publisher are exposed to potential copyright infringement claims from the performer.

ContentID

ContentID is the system YouTube uses to automatically detect an infringing use of music in videos, place advertising in the videos and then distribute revenue to the rights holder (your library music publisher). Many publishers go through an intermediary (ContentID partner) such as AdRev or EMVN, who handle the administration in return for a share of the income.

Cue

In film and broadcasting, a ‘cue’ is a piece of music or sound design with a title and a composer.

Cue Sheet

A ‘cue sheet’ is a form which editors or music supervisors are required to fill out. It contains the cue title, composer and publisher details, as well as timing information stating when the cue appears within the production. This allows the company they work for to be sure that all rights are cleared, and when submitted correctly to the PRO (Performing Rights Organisation), makes sure broadcast royalties are distributed correctly. Notoriously, this is not done meticulously by editors of the world. You are losing money as a result, and you need your publisher or their agents to be using a tune-detection service like BMAT or Tunesat to catch unlicensed uses.

Custom Music

See article 4. Custom music, aka bespoke music, is created especially for a particular use. Fees are typically much higher than library fees, but there is also usually an expectation that you hand over all your rights, meaning you’ll probably never see repeat uses from the same music as you can with library music. Along with commercial music, custom music is the main competitor to library music in the TV and advertising worlds.

Cut-Downs

Library publishers and their clients often expect very accurately timed cut-downs or ‘edits’ of the main versions of your tracks at 15, 30 and 60 seconds’ duration.

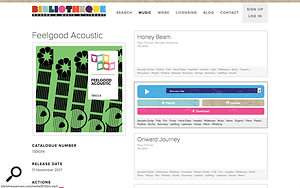

Once upon a time, library music was distributed on vinyl, then CD. Today, distribution is invariably online.Distribution Platform

Once upon a time, library music was distributed on vinyl, then CD. Today, distribution is invariably online.Distribution Platform

A library music distribution platform is a software or cloud-based system for organising your audio, cover art and metadata and sharing it all with agents and clients around the world. The biggest platforms in library music are Harvest Media, SourceAudio and Soundminer.

End Riser

In trailer music (see articles 6 and 7) the end riser is the final overpowering crescendo of a trailer, typically stopping suddenly with no resolution to give a sense of a tense cliffhanger that can only be resolved by going to watch the movie.

Endings

See article 4. Clients say that the way your track ends is one of the most important factors in it being chosen or rejected. A great, punchy end will sit well with an edit point in a video, while a weak or fade-out end will not.

Exclusive Publishers

See article 2. Traditional library publishers, who ask for exclusive ownership of the music in return for their greater marketing pull, are often referred to as ‘exclusive publishers’. Note that this doesn’t mean that you are tied to only working for one publisher, as is often the case with non-library music publishers: deals are done on an album-by-album basis.

Finishing

‘Finishing’ is a term from the Hollywood trailer world denoting the successful selection and use of a trailer by a major film studio in a world where many independent advertising agencies (known as trailer houses) compete for the same movie marketing campaign.

Future Of The Industry

See articles 2, 8 and 9. There are pessimists who predict the library music market being flooded by low-quality music, perhaps produced by AI, and new business models that push prices down, forcing royalty earnings downwards (aka a ‘race to the bottom’). Meanwhile there are optimists who see a massive new market in the growth of online video, believe that very high-quality music will always attract a premium price, that many very large clients are willing to pay for quality, speed and reliability and that investing in high-quality sales and customer service staff will give a personal touch that giant online portals can never compete with. Unforeseen economic problems or radical technology shifts could also influence the market, but until proven otherwise, this writer remains an optimist!

Get Rich Slow Plan

See article 1. Place 50 great tracks per year with high-quality library music companies and, barring disasters, you have a high chance of earning over £100k per year in royalties after about eight years.

Great Library Music

There are always exceptions, but publishers (article 9) and clients (articles 4 and 6) generally offer consistent advice for making great and successful library music. Desirable qualities include being minimal, upbeat, having good endings, good intros, good titles and authenticity.

In Perpetuity

‘In perpetuity’ ownership of your music is expected by large traditional music libraries and means ownership for the life of copyright (until 70 years after your death, when the music becomes public domain).

In-house Libraries

Most large TV networks and production companies have their own ‘in-house’ music libraries, consisting of work formerly used in their own productions. Because this saves the company money, they might be tempted to ask their editors to favour this music, and therefore the growth of in-house libraries is seen as an increasing threat to regular library music publishers.

Income Prediction

See article 1. A rough rule of thumb is that, after a three-year delay, you should expect your library albums to earn an average of £5000 each every year from sync and broadcast royalties, gradually declining after seven or eight years. The more music you write, the more reliable this rule becomes. If you’re earning a lot more than this, then well done: you have great music and a great publisher. A lot less? Something needs fixing!

Infringement

See article 8. Copyright infringement is going on everywhere. You might be accidentally using someone else’s tunes or reusing your own. Someone might be giving away your music on a torrent site. A scammer could be claiming your music as theirs. A production company in a far-off land might be using your music everywhere and getting away with it. Solutions include tune-detection software to catch people, ContentID partners to make money out of it, and professional indemnity insurance to bail you out if you a case goes against you.

Interested Party

An ‘Interested Party’ is someone with a relevant role, such as a writer, arranger or publisher, who will have their IPI number embedded in the metadata and registered with a PRO, with a right to some broadcast (‘performance’) royalties and possibly some right of refusal for sync clearance. However, the pre-cleared nature of library music means that in fact no contracts will allow any such refusal or ‘moral rights’.

Library Music

Also known as production music or stock music, the library music industry has been offering pre-cleared broadcast-friendly music for 90 years.

Well-played live instruments will always help to elevate your music above the herd.Live Instruments

Well-played live instruments will always help to elevate your music above the herd.Live Instruments

If the genre isn’t electronic and you or your publisher can possibly afford it, make all your music with some or all well-played live instruments. The quality, authenticity and emotional depth of committed musicians is in high demand from clients and will continue to outshine other options until the AI overlords replace us all.

MCPS

The UK’s MCPS (Mechanical Copyright Protection Society) is one of several centralised rights societies in the world which play a dominant role in library music by offering clients a fixed price list for sync licences on behalf of hundreds of major library music publishers. If a publisher is an MCPS member, it cannot grant independent licences or negotiate prices, but must direct its clients to the MCPS, where they will always pay the standard rates. This system works well for large libraries, but smaller libraries can arguably stand out and get more business by not being members, meaning that they are able to offer discounts or flexible rates. Confusingly, despite having the word ‘mechical’ in the name, the main work of the MCPS is to grant synchronisation (sync) licences for library publishers, although they do grant mechanical (mech) licences too.

Mechanical (Mech) Income

Mechanical (often shortened to ‘mech’) income is from licences granted for the use of music as part of a manufacture, for instance in trailers, menus and extras included on Blu-Ray discs. This income stream is collected by your publisher alongside synchronisation (sync) income and shared with you as per the terms of your Writer Agreement.

Accurate, comprehensive metadata is vital in order to get your tracks used by clients.Metadata

Accurate, comprehensive metadata is vital in order to get your tracks used by clients.Metadata

See articles 4 and 9. Metadata is information associated with each music cue including descriptions and key word lists (which help search engines to find your track) as well as your CAE number, publisher, royalty splits, music genre, instruments used and much more. The information becomes embedded in the audio files so that clients can quickly find the right music and the correct cue-sheet information.

Mistakes

See article 8. Other people’s errors include your publisher, agents, clients and performing rights societies doing typos and mixing up tracks, titles and writer names. Most data input is still largely manual and mistakes do happen. Writer mistakes (see articles 3 and 8) include reusing the same musical ideas in multiple tracks (causing infringement issues), uploading your music to YouTube without your publisher’s permission, publically admitting to being inspired by another writer’s music (so inviting infringement claims), adding compression to your stereo output channel in an unmastered mix, being unreliable, argumentative and endless other sins.

Mixing

See article 3. Most publishers prefer you to do your own mixes, meaning that the most successful library music writers will also be excellent producers and mixing engineers.

Moral Rights

Unlike traditional music publishing contracts, library music contracts will always expect you to ‘waive your moral rights’ meaning that you have no right to object to any possible use of your music. This is necessary for the benefit of making the catalogue widely available for instant licensing by clients, but does open the risk to your music becoming launch party music for a new fighter jet, or a diabolical politician’s chosen rally anthem.

Motivation

See article 3. Library music is a long game, and staying motivated can be difficult for many writers. Classic motivational business books like Think And Grow Rich (1938) can be an excellent source of motivation — as can remembering that your long term success and paying off your mortgage depends on a steady output of at least 50 tracks per year for great library music publishers.

Music Supervisor

The role of Music Supervisors (aka ‘supes’) at trailer houses and in movie productions is to know the best music out there, help video editors to find it, organise it well on internal server systems and have a good understanding of licensing law to make sure cues have the proper clearance (permission from all Interested Parties). They are powerful gatekeepers, so your publisher needs to keep them happy.

Music Theory

See article 3. The amount of music theory knowledge you need is a purely practical consideration for library music. If you make sound design and simple drones you don’t need so much theory, whereas scoring live string parts will need more training. That said, you can manage by leaning on a professional orchestrator if it’s only for the occasional job.

“I’m just checking if it has a needledrop licence.”Needledrop Licence

“I’m just checking if it has a needledrop licence.”Needledrop Licence

Harking back to vinyl days, a ‘needledrop licence’ is a common US term for a synchronisation licence.

Neighbouring Rights

In some countries, ‘neighbouring rights’ are a significant source of composer income. The term refers to broadcast income paid to performers rather than writers of library music. In the UK, this type of income is generally collected by the PPL, but they explicitly exclude library music, so you’ll get better luck elsewhere.

Network Approved Lists

See article 4. A ‘network approved list’ is a list of ‘approved vendors’ created by the management at TV networks such as Fox, CBS and Discovery, where internal and external video producers are encouraged to use only library music from these lists. Gaining approval will significantly help your publisher to earn royalties for you and depends on the network thinking the music is good enough, the prices are right and you’re not overly duplicating what they already have.

Desperate for a bit of human company? Organisations representing composers and publishers offer numerous networking events.Networking

Desperate for a bit of human company? Organisations representing composers and publishers offer numerous networking events.Networking

See article 5. Join lots of forums, composer societies such as Your PRO and BASCA and Facebook groups, and regularly check online for news of gatherings, workshops and awards. You’ll pick up tips and gossip from fellow composers and feel less alone in this oddball career which typically leaves everyone working on their own in front of a computer all day.

Networks

See article 4. TV networks, known as broadcasters in the UK, include companies like the BBC, ITV, CBS, HBO, ABC, Discovery, Fox and so on, and are a prime target for all good library music companies thanks to the high sync and performance income that can be generated from wide usage in popular shows.

Non-exclusive Publisher

See article 2. In library music, a ‘non-exclusive publisher’ is the label composers give to publishers who don’t take ownership of your copyrights and allow you to place the same music with other non-exclusive publishers. This is a preferred option for many composers, but my experience is that the bigger fees often come from the exclusive publishers, who may invest more time and money in marketing and quality control.

Payment

See articles 1 and 2. Typically, in library music you will be paid four times per year from your PRO for your performance (broadcast) royalties and twice per year from your publisher for your sync and mechanical royalties. Of the latter, the vast majority is likely to be money paid to them by their agents in other territories. The relative amounts of performance and sync/mech income depend on the type of publisher you have: TV-friendly publishers make greater performance income, while trailer music publishers can make greater sync income.

Performance Income

See ‘PRO’. Performance income is mostly money paid by a network (broadcaster) when music has gone on air within a TV show, to a PRO such as PRS, who then pay the money to writers and publishers.

Placement

The term ‘placement’ is often used by library composers and publishers to refer to a cue being successfully used on a video production of some kind. Placements on major movie trailers and car ads are humblebragged about the most on Facebook by all concerned (“so honoured to be a part of Paramount’s awesome campaign”), while placements on ads for embarrassing products usually get a jokey brag treatment, but a brag nonetheless.

Popular Genres

Large library publishers may want to cover most better-known genres with at least one album, but some enduringly successful styles include mainstream indie-rock, emotional orchestral music and plinky-plonky lighthearted ukuleles.

PRO (Performing Rights Organisation)

See articles 1 and 2. The PRO is the main long-term source of income for most library music writers. Performing Rights Organisations, which include PRS in the UK and ASCAP and BMI in the USA, collect what they call ‘performance’ royalties from broadcasters (TV networks) whenever a piece of music is aired on the channel. Confusingly, the ‘performance’ refers to the broadcast of the music show, as if the broadcast is a public performance. The ‘performance’ income is collected for publishers and writers, not performers.

Production Music

Another term for ‘library music’, ‘production music’ came to prominence as a term in the 1990s when the industry wanted to reinvent itself as a high-quality supplier of music for plush productions, disowning a reputation for cheesy low-budget light elevator music that it acquired in earlier decades.

Productivity

Part of library music success involves writing a lot of music: not by rushing and working long hours, but by being efficient and decisive. See article 3: healthy habits, writing clear to-do lists of what you want to achieve with each track, and only developing your best sketches will increase your productivity.

Accidents in the recording studio do happen — as do accidental copyright infringements. Protect yourself by taking out indemnity insurance.Professional Indemnity Insurance

Accidents in the recording studio do happen — as do accidental copyright infringements. Protect yourself by taking out indemnity insurance.Professional Indemnity Insurance

See article 8. Professional Indemnity Insurance, also known as Professional Liability Insurance and Errors And Omissions Insurance, could protect you from being bankrupted by a copyright infringement accusation.

Professionalism

See article 3. Professionalism means taking feedback well instead of being defensive, putting in your best efforts, doing your listening research, being honest and hitting deadlines.

Promo (TV Promo)

TV promos, usually called just promos, are adverts for TV shows, and often use library music because it is a fast, pre-cleared high-quality option compared to the slow, uncertain process of commissioning custom music and the clearance problems that can come with commercial music.

Publisher (Independent)

Independent publishers could have the down side of being unpredictable — the owner could die, or get bored, or sell the catalogue — but the up side is that they are often highly committed and energetic about growth and placements for all of their small catalogue.

Publisher (Major)

Major publishers could have the down side of having so much music they don’t particularly push yours, but the up side of having A-list clients with big budgets.

Publisher’s Share

In royalty splits, the Publisher’s Share is their split of synchronisation (sync), mechanical (mech) and performance royalties after you’ve had your Writer’s Share.

Recoupment

Recoupment means publishers taking back some of their initial cash outlay before they pay your royalties. That outlay could include advances and a share of production costs. It’s important to check your Writer Agreement carefully before signing, because this could be the difference between you seeing sync/mech royalties in a year or two, or pretty much never.

Reversion Clause

In publishing and recording contracts a ‘reversion clause’ states that the ownership will return to the Writer after a specified term, or under certain conditions. No traditional library music publishers offer such a clause: they want your music in perpetuity, so that they can build up long-term value in a fixed set of recordings which clients can depend on to stay pre-cleared and and available, rather than risk having them randomly taken out of the catalogue without anyone realising.

Royalties

Royalties are your income from library music: your ongoing share of any money generated by the licensing of your music. Long-term library music writers, like book authors, pop stars and inventors, understand that royalties are far more stable and significant for your future security than one-off fees from individual jobs.

Royalty-free Libraries

See article 2. Royalty-free libraries are online music portals that ask for an initial fee and then allow the user to use your music in any production with no further royalties payable. They are typically non-exclusive and have a reputation for catering for the lower end of the market, but this has changed in recent years, as large new companies have taken market share from traditional libraries.

Signature Sounds

See articles 6 and 7. ‘Signature sounds’ are memorable sounds on movie trailers that fit well with the characters or mood of the film, and are in high demand.

Sound Design

See articles 6 and 7. Sound design is the creation of processed sounds that could include minimal atmospheres, rising sounds (risers), slams, drops and whooshes.

Soundalikes

See article 9. Once a highly popular way to satisfy the client’s need for library music that sounds like a well-known commercial artist or song, thanks to a series of copyright infringement court cases, most library publishers now want to steer clear of ‘soundalikes’ to stay out of trouble.

Stems

Now hugely popular with video editors, ‘stems’ are a series of say five to 10 stereo audio tracks that group and submix together your major sound types (for instance, brass, guitars, bass, drums and percussion); playing all of the stems simultaneously would reproduce your mix. Editors love the degree of control they can get by changing levels, muting, looping and chopping up stems to work with their visuals.

Sting

A sting is a short piece of sound such as a stab or chord which has the character of your main track, but which can be used on its own as an ending or to sync to an edit or transition.

Sub-publisher

See ‘agent’.

“Your sync licence does not include the territory of Skaro! You will be exterminated!”Synchronisation (Sync) Licence/Royalties

“Your sync licence does not include the territory of Skaro! You will be exterminated!”Synchronisation (Sync) Licence/Royalties

Synchronisation is the legally significant moment when an editor drops your music into their video timeline and synchronises it to the video. Publishers collect fees for sync licences and, depending on the split in your Writer Agreement, will hopefully share some of that with you.

Term

In contract law, the ‘Term’ is the length of time that the contract lasts for. This is often forever (‘in perpetuity’).

Theatrical Trailer

See articles 6 and 7. The ‘theatrical’ trailer is the main official trailer for a movie, which is licensed to show in cinemas and commands the highest fees for music licences.

Three Year Rule

See article 1. Thanks to a series of delays by your publisher, their agents, clients and broadcasters you can expect a three-year delay between finishing your music and starting to see royalties. Therefore, be patient and keep writing new music while you wait.

It worked for Shakespeare, and the three-act structure will work for you, too.Three-act Structure

It worked for Shakespeare, and the three-act structure will work for you, too.Three-act Structure

See article 7. A classic structure for a movie trailer and therefore its music is to have three acts: a mysterious or tense intro and a high-powered middle building to an overwhelming ending, perhaps with a few gaps for blockbuster one-liners.

Titles (importance of)

See article 3. Great titles have a big influence on how much money your library track will earn, because editors are busy and will use the title as their quick guide. A perfect title will be general enough to suggest that the track will work in many contexts, rather than narrowly specific, evocative and inspiring, not boring, and will give a clear indication of the mood and style, rather than being vague or unhelpful.

Trailer House

“I’m looking for a trailer house...”See articles 6 and 7. Concentrated north of LA, trailer houses are independent ad agencies that specialise in creating movie trailers, with the major movie studios as their clients.

“I’m looking for a trailer house...”See articles 6 and 7. Concentrated north of LA, trailer houses are independent ad agencies that specialise in creating movie trailers, with the major movie studios as their clients.

Trailerisation

See articles 6 and 7. Trailerisation is the process of taking a piece of music and pumping it up to sound amazing on cinematic sound systems by adding awesome sub-bass booms and other sound design.

Trailers

See articles 6 and 7. Movie trailers use a lot of library music: often specialist trailer music, but potentially, anything that will work for the film they are promoting.

Trends

See articles 6, 7 and 9. Do you stay timeless for longevity, or follow trends to stay current? It’s all a gamble, so a safe option might be a bit of both.

Tune Detection Software

Companies like Tunesat and BMAT monitor worldwide TV networks matching the audio to your music in order to log placements and potentially catch unlicensed uses. Tunesat have a free tier for composers with a limited number of tracks, and count large publishers as their major clients.

TV Spot

In the movie trailer world (see articles 6 and 7) a TV spot is a short movie trailer designed to be shown on TV. This commands a lower fee than the major ‘theatrical’ trailer, but still offers good rates.

Underscore

An underscore is a minimal piece of music in a video designed to create a mood without distracting you from dialogue.

Upbeat

Sad or mysterious music has its place in documentaries, promos and trailers, but for advertising and general TV use, upbeat music is king. So cheer up, strum your ukulele and get clapping.

Writer

In library music publishing a Writer is usually just the music composer because most library music is instrumental, but it could also be the lyricist if there are words. A central role in the industry, Writers (written with a capital W in contracts) get to join PROs, sign Writer Agreements with publishers and take their Writer’s Share of royalties.

Writer Agreement

The Writer Agreement is the contract between the composer and the publisher.

Writer’s Share

In both performance income (from PROs) and sync/mech income (from library publishers) the Writer’s Share is the split of royalties going to the writer (composer) of the music.

Final Words

If you’ve been reading this series carefully, you’ll now know that library music remains a thriving and multifaceted industry despite occasional grumbles of pessimism from some writers and publishers. You’ve learned that if you write at least 50 great tracks per year for great library publishers you’ll earn well, but you will have to be extremely patient and productive, because the royalties take years to build up and very much depend on how much material you have out there.

You’ve learned that benefits of the library life include working from home, artistic freedom, new challenges, flexibility in your chosen projects and hours, and not having to court the radio and press while remaining forever young, fashionable and beautiful. You don’t have to pander to a TV or film director’s confusing vision, and you’re also not endlessly chasing one-off fees as custom music writers are. Eventually, you will be able to float along nicely on your magic royalty carpet.

Along the way, you’ve learned that every library publisher has a different ethos, musical style or business model and you should therefore do your research before contacting them. You’ve learned that above everything your music has to have authenticity while being generally positive and minimal because that’s what the market wants.

You’ve learned that your best bet to get started is to listen to a lot of great library music albums, research the best publishers and send them a link to a well-titled album of 12 new tracks that sound amazing, fill a gap in their catalogues and sound like something they would release. You’ve also learned about the glamorous world of Hollywood trailer music, and perhaps been intimidated by the low odds of success in a highly paid, competitive market.

In fact you’ve learned to be polite, professional, persistent, patient, positive, productive and practically perfect, and therefore really have no excuse not to go out, make your millions and meet me for a party in a champagne-filled pool in Malibu in 2027, full of ageing library composers who haven’t been out of the studio for 10 years talking about Cubase and stem exports. It’ll be a blast, to an extent.

The small catch is the need to be a great writer and producer, and to work full-time with no income to pay the bills for a few years while you wait for royalties to build up, crossing your fingers that your publisher, the library industry or the world economy don’t collapse, or you get sued by Eminem for copyright infringement. Pitfalls and promises aside, I can say from long personal experience that it’s a great niche to be in and it could be a great opportunity to spend your life making music all day on a nice income, without having to get a real job.

Further Reading

The Business Of Music Licensing by Emmett Cooke covers a wider area beyond library music, but gives excellent tips:

www.thebusinessofmusiclicensing.com

The previous articles in this series, which began in May 2017, are also highly recommended if you don’t have them. Options for getting them include ordering print issues of Sound On Sound, getting a digital subscription or buying and downloading individual article PDFs:

All About Library Music: Part 1 Getting Started

All About Library Music: Part 2 The Business

All About Library Music: Part 3 The Composer

All About Library Music: Part 4 The Client

All About Library Music: Part 5 Networking

All About Library Music: Part 6 Hollywood Trailers

All About Library Music: Part 7 How To Write Trailer Music

All About Library Music: Part 8 Avoiding Disaster

About The Author

Dan Graham has composed library music since 2004. From 2010, he started a series of library music publishing companies, which include Gothic Storm Music and The Library Of The Human Soul. He also co-owns Gothic Instruments, developers of the Kontakt-based Dronar, Sculptor and BeatTrix series of virtual instruments.